Crockett Johnson’s Books: Collaborations

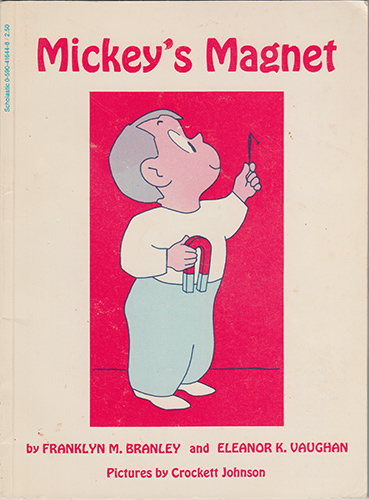

Written by Franklyn Branley and Eleanor K. Vaughan, Illustrated by Crockett Johnson

Mickey’s Magnet (1956)

Including a real magnet (lightly glued to the inside of the back cover), this book tells the story of how Mickey learns about magnets — what they pick up, what they don’t, and why. The final page encourages the reader to use the enclosed magnet to experiment: “Here is a magnet you can use,” it offers. “Mickey picked up pins with a horseshoe magnet,” it continues. “Can you pick up pins with your bar magnet? … What else can you find out about your new magnet?”

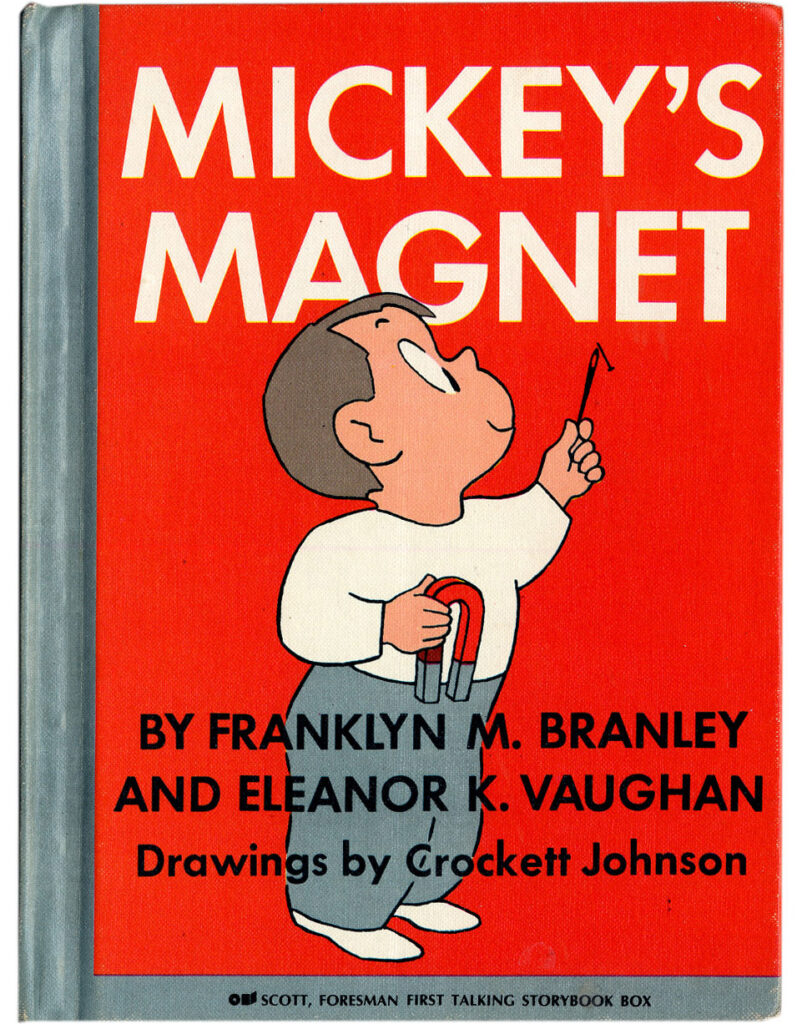

Thanks to Chris Ware, here’s the Scott, Foresman Company edition from 1967. It includes a record (both sides shown at right), and a box in which to place both record and book.

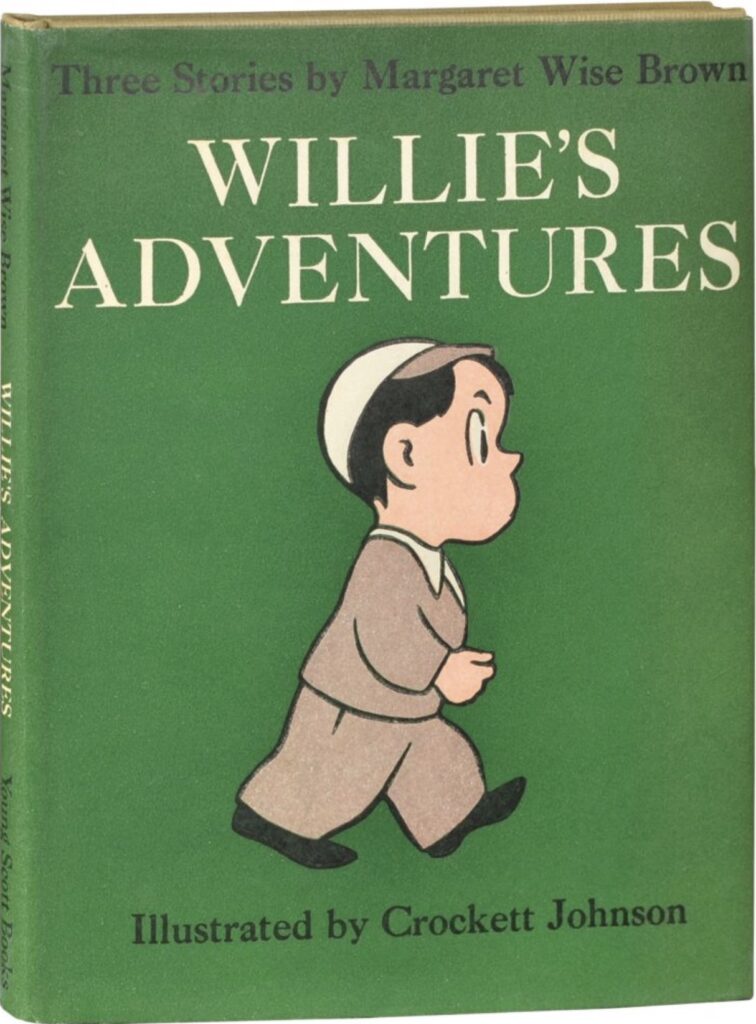

Written by Margaret Wise Brown, Illustrated by Crockett Johnson

Willie’s Adventures (1954)

In “Willie’s Animal,” the first of three stories about Willie, he phones his Grandmama to tell her, “I would like a little animal of my very own.” She sends him one, in a box — but what will it be? For much of the next day, Willie wonders what sort of animal will arrive; when his mother returns home, she pries open the box, and Willie meets his new animal.

“Willie’s Pockets” finds Willie wearing his new seven-pocketed suit. “Seven empty pockets. What to put in them?” During his day, Willie tries placing different items in them until he finds just the right sorts of things for his pockets.

The final story, “Willie’s Walk,” chronicles Willie’s walk from his home, in a small town, to his grandmother’s house, in the country. He sets off to Grandmama’s all by himself, undaunted by wild flowers, butterflies, or even a small stream.

Written by Bernadine Cook, Illustrated by Crockett Johnson

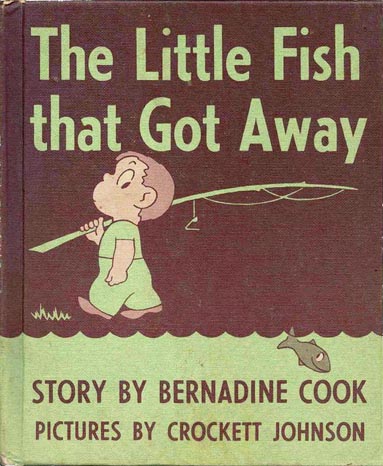

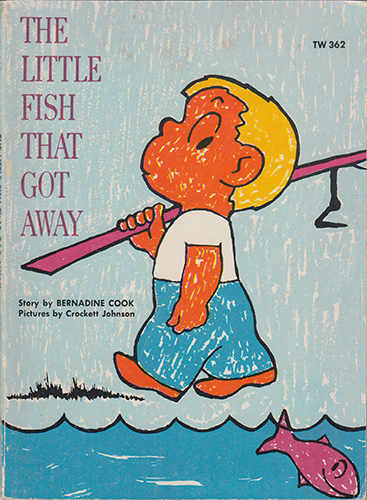

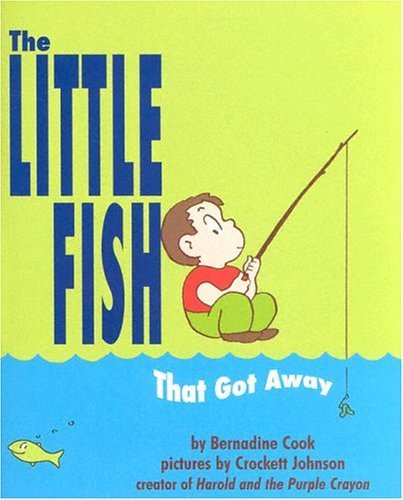

The Little Fish That Got Away (1956)

“Once upon a time there was a little boy who liked to go fishing. There he goes, over there on the other page.” Bernadine Cook’s story begins like this, and often makes reference to Crockett Johnson’s illustrations, “like this.” The boy never caught any fish: “But ONE day…” (if I tell you any more, I’ll give away too much).

The Little Fish That Got Away is also available in Dutch and in Japanese.

Written by Constance Foster, Illustrated by Crockett Johnson

This Rich World: The Story of Money (1943)

A 160-page primer on money, this book seems aimed at slightly older children (5th-graders, perhaps). It explains what money is, how it works, when it was invented, and other economic topics (like inflation, taxes, and banks). The book does cover money of various countries, but it assumes its reader to be an American: current mentions of money always refer to U.S. dollars. Though it lacks regular characters (or, for that matter, a story), a drawing of a boy often stands in for “you.”

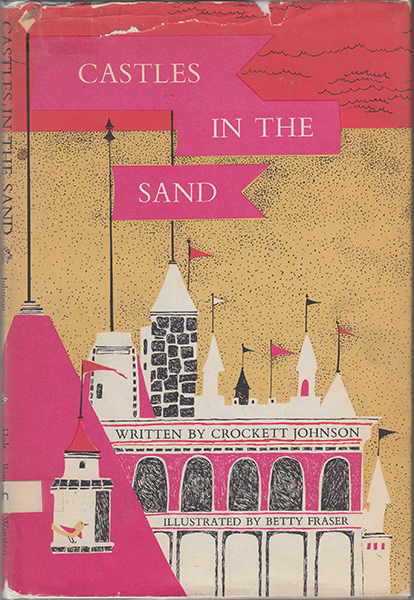

Written by Crockett Johnson, Illustrated by Betty Fraser

Castles in the Sand (1965)

“I wouldn’t mind if we were in a story,” said Ann. “Because in stories people don’t go around all day looking for an old shell. Interesting things happen.”

“Nothing really happens in a story,” said Ben. “Stories are just words. And words are just letters. And letters are just different kinds of marks.”

In the story that follows, words soon become real, proving Ben wrong. Castles in the Sand is one of Johnson’s more interesting speculations on the power of imagination, and would be a fine companion volume to A Picture for Harold’s Room.

Later published as Magic Beach (2005), featuring Johnson’s original illustrations and original title.

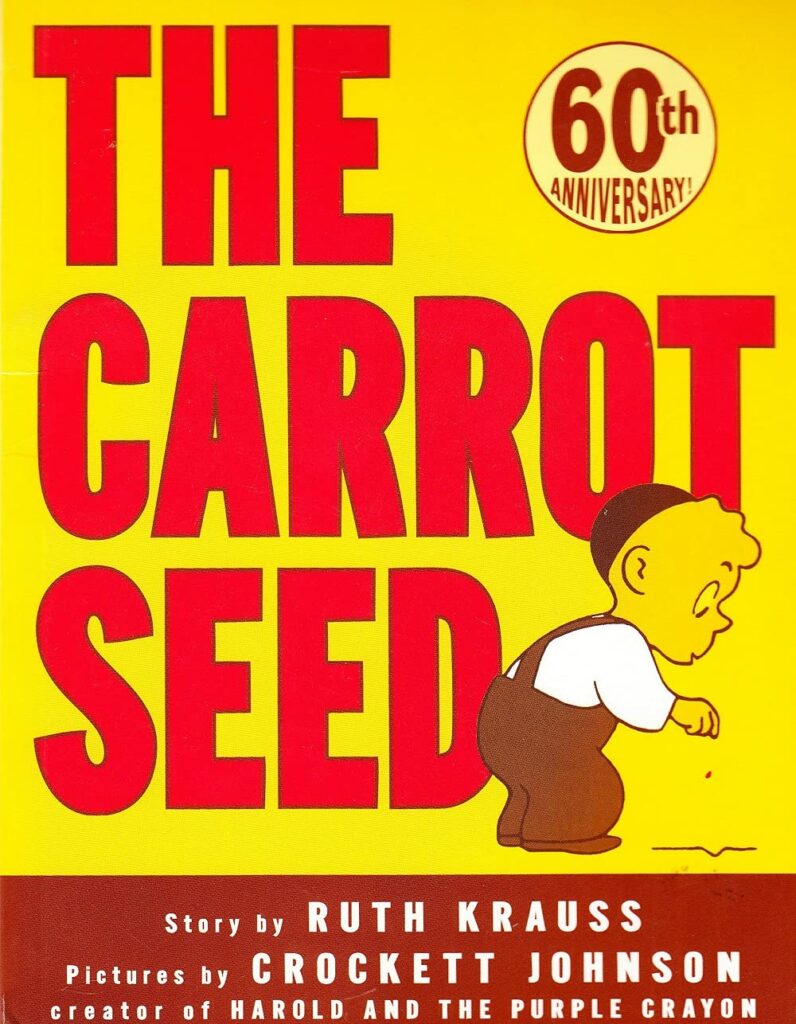

Written by Ruth Krauss and Illustrated by Crockett Johnson

The Carrot Seed (1945)

His mother, father, and big brother all say that “it won’t come up,” but the little boy tends to his carrot seed nonetheless.

Asked what books he would select for his “Western Canon for children,” Chris Van Allsburg told HomeArts that, in addition to Harold and the Purple Crayon, he’d choose The Carrot Seed.

In his essay “Ruth Krauss and Me,” Maurice Sendak praises “that perfect picture book, The Carrot Seed (Harper), the granddaddy of all picture books in America, a small revolution of a book that permanently transformed the face of children’s book publishing. The Carrot Seed, with not a word or a picture out of place, is dramatic, vivid, precise, concise in every detail. It springs fresh from the real world of children.”

Also available in Spanish and as a song.

How to Make an Earthquake (1954)

Just as Krauss’ A Hole Is to Dig (1952, illustrated by Maurice Sendak) offers definitions invented by children, How to Make an Earthquake presents activities that appear to have been invented by children. For example, consider “How to balance a peanut on your nose” (pictured at left): “Put a sticky raisin on top of your nose. Then, take a peanut and stick it on top of the raisin.” And, if “you don’t have any raisins, you could use some other sticky thing.” You can also learn “A good way to entertain telephone callers,” “How to learn acting,” and, of course, “How to make an earthquake.”

Is This You? (1955)

A precursor to Dr. Seuss and Roy McKie’s My Book About Me (1969), Is This You? asks the child a series of questions (“Is this your family?”, “Is this where you live?”, “Is this where you go to school?” and so on), and invites him or her to compile a book, a page at a time, in response to each query. Each question accompanies amusingly absurd illustrations. For instance, the illustrations with “Is this where you live?” show a child in a doghouse, under a toadstool, and in a telephone booth. On the “Is this your friend?” pages, we see a child pictured with an egg, a giraffe, and even Mr. O’Malley! Following such a question, a small stick-figure intervenes to tell you to “Take another page of your paper and draw where you live” or to “draw your friend.”

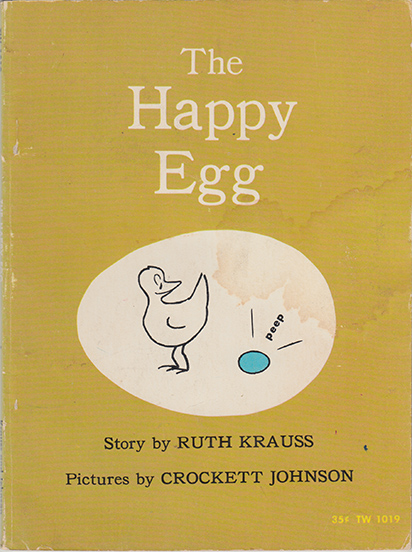

The Happy Egg (1967)

The last children’s book Johnson had a hand in, The Happy Egg tells of a little bird’s life from egg to flight. As in The Carrot Seed, a good portion of the book is spent waiting (but, this time, waiting for an egg to hatch).