Crockett Johnson’s Early Work

In 1927, after leaving his position in Macy’s advertising department, Crockett Johnson began working as the art editor for some of the McGraw-Hill Publishing Company’s trade magazines, a job he held until roughly 1936. During this period, he also did free-lance work — including cartoons for New Masses and the comic strip “The Little Man with the Eyes” for Collier’s.

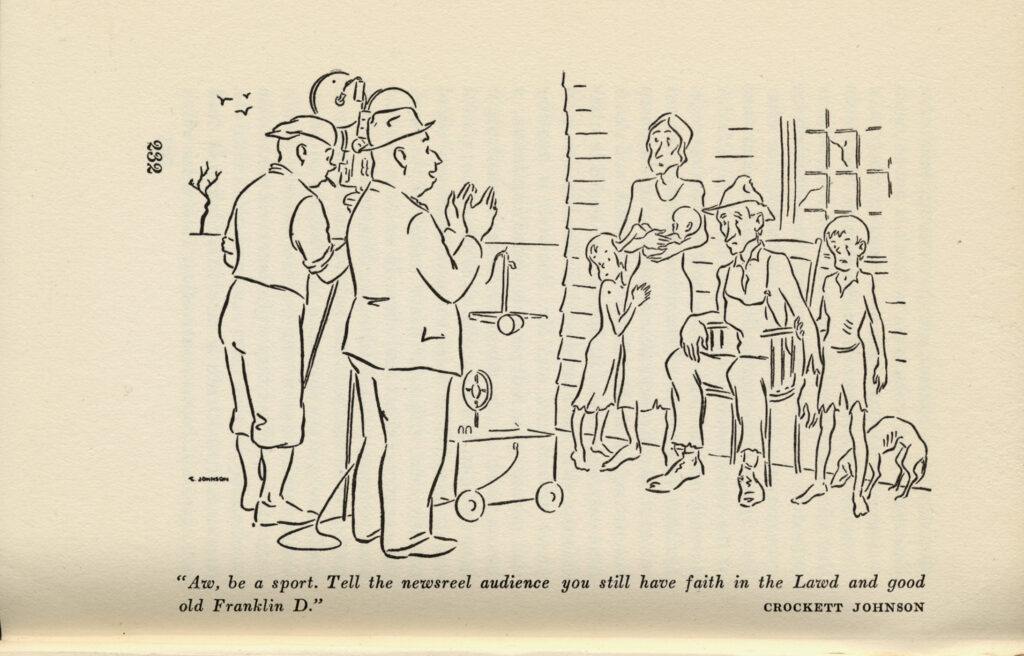

This page contains two cartoons from New Masses (including one of the two reprinted in Robert Forsythe’s Redder Than the Rose, which collects Forsythe’s essays from the weekly newspaper), and two from Collier’s.

For a bibliography of work from this period, see “Crockett Johnson’s Early Work: A Bibliography.” For more of Johnson’s New Masses cartoons, see the Marxists Internet Archive‘s scans of New Masses — which I wish had existed when I began this site or my biography of Johnson.

New Masses

In December of 1917, Woodrow Wilson’s Espionage Act shut down The Masses, a left-wing paper that began in 1911. Two months later, in February 1918, The Liberator took its place. That publication merged with the Communist Party’s Workers Monthly in 1924 and, in 1925, ex-Masses and –Liberator writers, editors, and artists got together to form The New Masses. Its first issue appeared in 1926. Johnson began contributing cartoons in 1934 and by August of 1936 was one of the paper’s editors. He appears to have stopped contributing cartoons after May of 1940. For a bibliography of Johnson’s cartoons for the paper, please click here; for a bibliography of his reviews for the New Masses, please see the main bibliography.

In “All Hectic on the Potomac,” the essay in which the above cartoon appears, Forsythe writes,

What baffles the gentlemen of Washington […] is the fact that the capitalist system, over which they hover so anxiously and which they nurse so tenderly, is rapidly sinking. It is struggling along under an oxygen tent, with Dr. Roosevelt supplying it at intervals with a new tank of artificial life, but it is not improving; it is merely being kept alive until the relatives can arrive. If the officials of Washington speak fatuously of the hopefulness in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, it is not because they feel there is hope in Idaho or elsewhere but because they cannot bear the thought of the end. (225-226)

He explains, “The capacity for illusion is endless and there are experts abounding on Pennsylvania Avenue to declare that all would be well if only Herbert Hoover were back, but neither Hoover, Roosevelt, nor the Great God Jehovah will cure the maladies of capitalism” (227), and Johnson’s cartoon suggests that newsreels help promote this “illusion” by encouraging audiences to believe that even the most destitute still “have faith in the Lawd and good old Franklin D.” Not incidentally, Johnson’s portrait of a starving family recalls Walker Evans’ photographs of sharecroppers, as well as similar photographs by Margaret Bourke-White and Dorothea Lange. The essay’s conclusion — which appears on the pages surrounding the illustration — reads as follows: “Capitalism is dead and there will be no resurrection. Interviews which omit that are not sources of information but exercises in evasion. Speeches which neglect it are speeches made into a rain barrel” (231, 233).

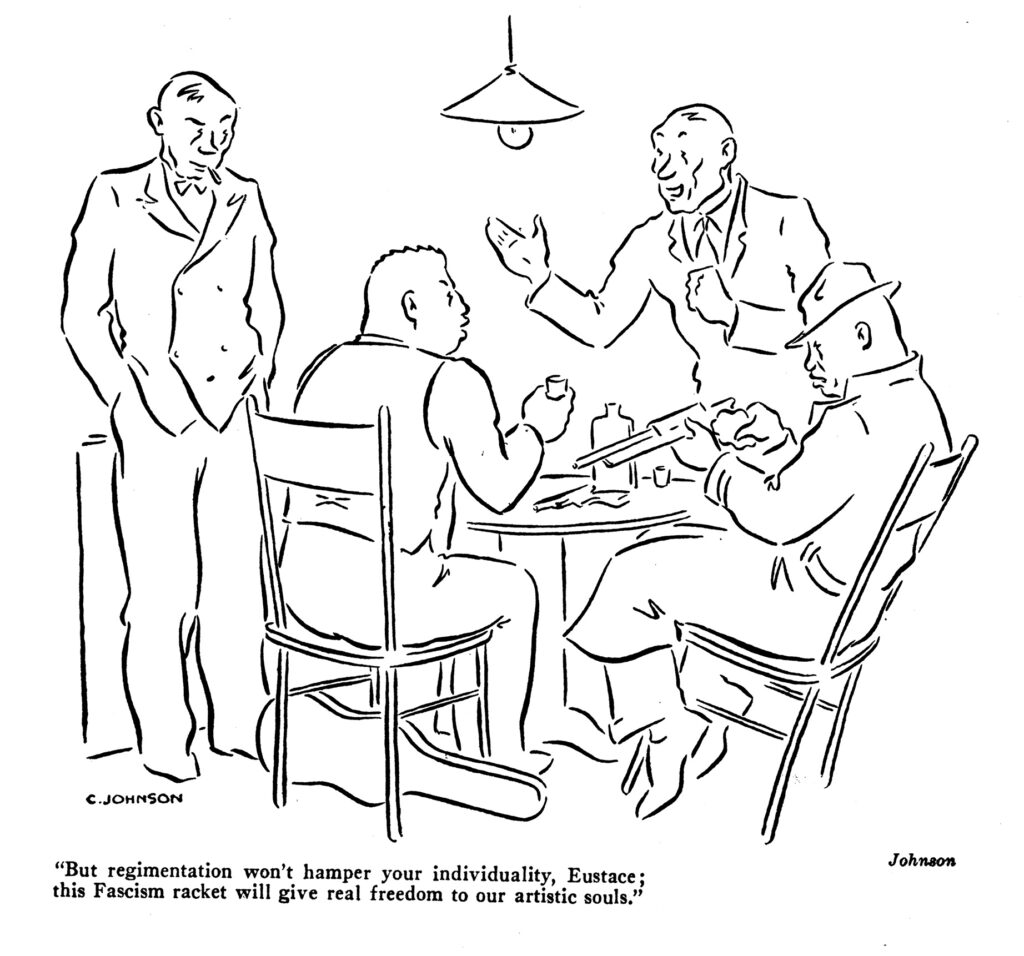

In the above cartoon, Johnson likens Fascism to a “racket,” run by a gang of thugs. Prohibition (the Eighteenth Amendment, which prohibited the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” in the United States) helped create a black market profitable for gangsters. On December 5, 1933, the Twenty-First Amendment repealed the Eighteenth, ending Prohibition (and creating a need for a new “racket” for “Eustace” and his friends).

At the same time, Fascism was gaining prominence both abroad and at home. Benito Mussolini became the leader of Italy in 1922, and Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933. In America, MGM’s film Gabriel Over the White House (1933) explored the appeal of Fascism: Walter Huston played a fictional new U.S. President named Judson Hammond. After a near-death experience, the weak leader received a visit from the Angel Gabriel, and was converted into a decisive dictator. By the time the above cartoon was published, Father Charles E. Coughlin, the popular Catholic priest whose radio programs reached virtually all of the American east and midwest, was turning towards anti-Semitic Fascism and preaching it to his listeners.

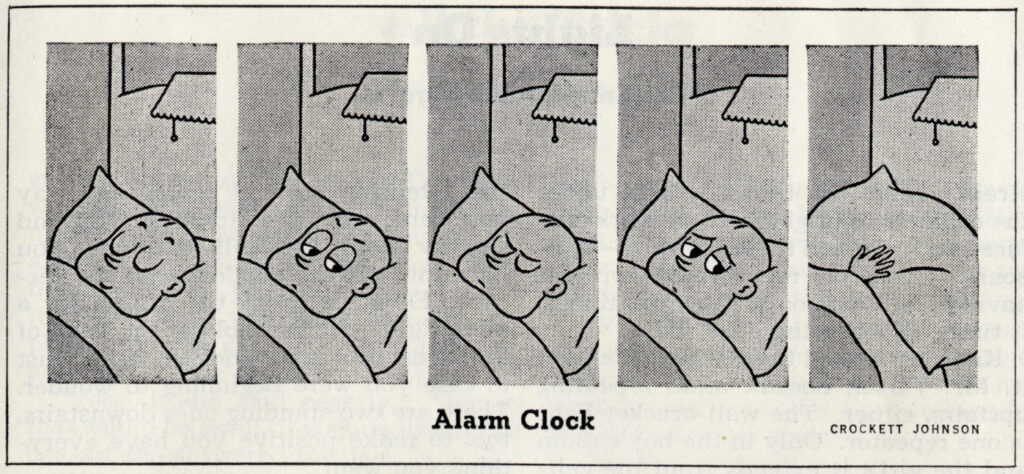

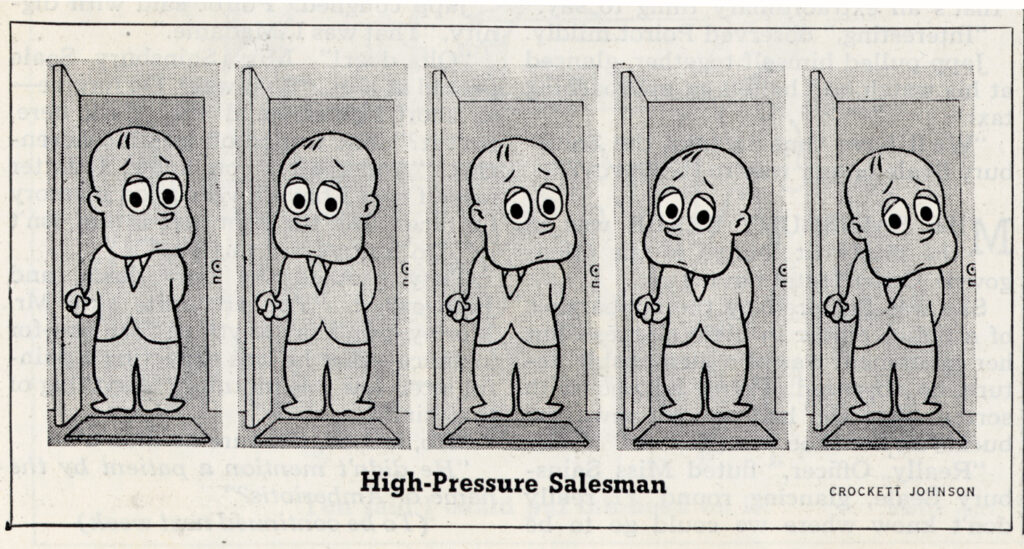

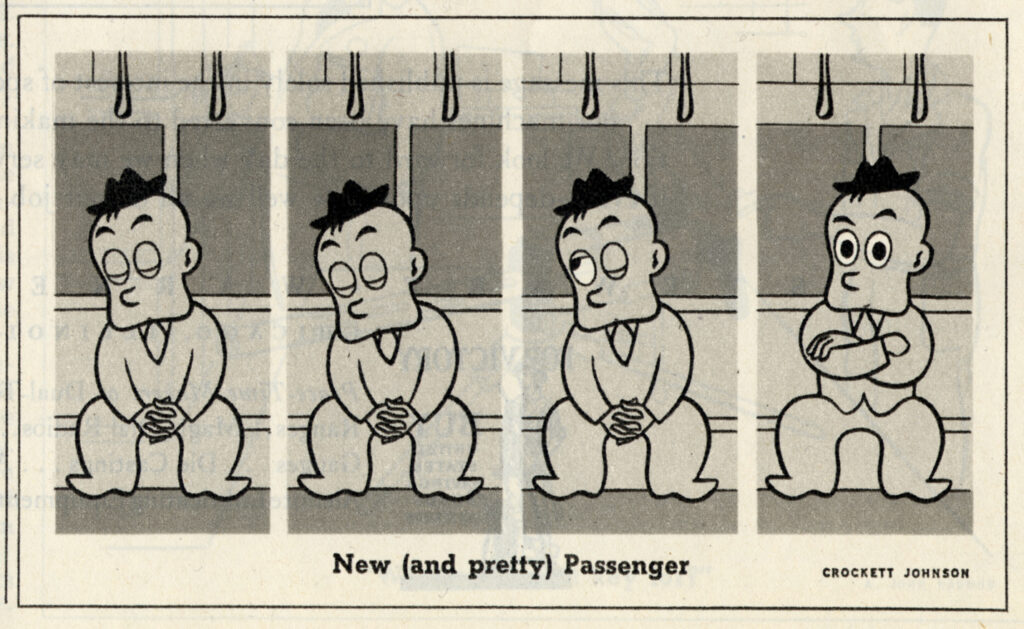

The Little Man with the Eyes

Although the strip never had an official name, it became known as “The Little Man with the Eyes” for its main character, a little man whose eyes communicate his thoughts to the reader and to others in the comic. I’ve seen about 95% of these strips and, in all of them, the little man speaks only with his eyes and not in words. Also, the “joke” can be subtle; you may need to look closely.

“The Little Man with the Eyes” ran in Collier’s from March 1940 to January 1943, and 13 strips were included in Collier’s Collects Its Wits (1941). For a bibliographic listing of the cartoon, please see “Crockett Johnson’s Early Work: A Bibliography.”