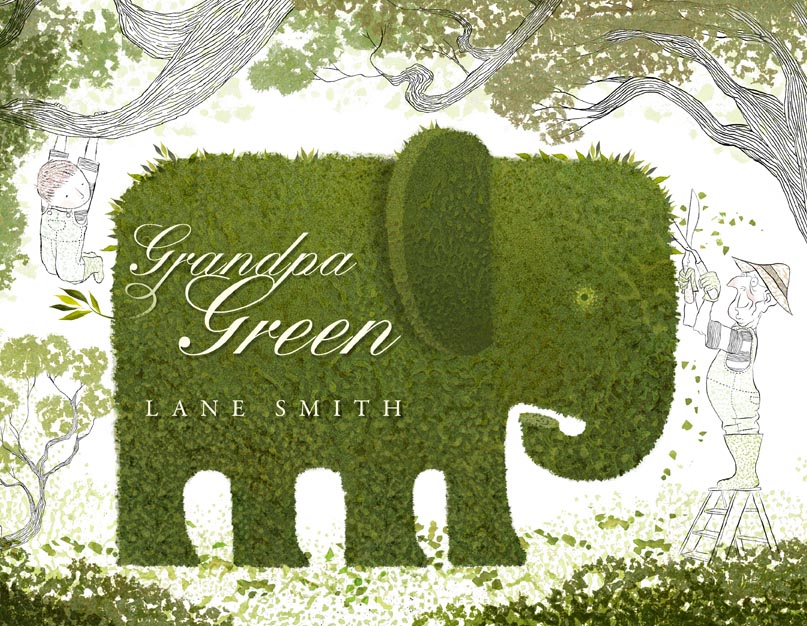

The capacity to surprise is a sign of a true artist. Though famous for his visual and verbal wit, Lane Smith has written a gentle, moving book about growing old. Grandpa Green has humor, but it relegates its sole joke to a footnote. (After reporting that in fourth grade, Grandpa Green “got chicken pox,” Smith adds an asterisk and a note to assure us “Not from the chickens.”) Minimal prose combined with a mostly green palette conveys a subtly elegiac quality, as if recollecting a near future in which Grandpa Green’s garden is all that remains of him.

Grandpa Green’s topiary depicts the major events in his life. In spare text, the narrator – a young boy strolling through the garden – says a few words about each event. And I do mean a few words. Most pages have less than a dozen. On the first, “He was born a really long time ago” has informal diction, suggesting that the boy is a confidant of ours. Next to those words, a baby-shaped topiary appears to be crying. Turn the page to discover that the water is fountaining up from a hose held by the boy. That’s the first of a series of visual cues – each two-page spread has one – hinting at the scene to come. The topiary rabbit leads us to a giant topiary carrot, because grandpa “grew up on a farm with pigs and corn and carrots…,” and, as the next two-page spread adds, “eggs.” The illustration of a topiary egg, chick, and rooster point to the chicken-pox joke, providing occasion, on the following two-page spread, to illustrate characters from the stories he read while recovering from his illness – The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, The Little Engine That Could.

Like the “Time Passes” section of Virginia Woof’s To the Lighthouse, Smith succinctly and swiftly moves us through the years, which – in Green’s case – offers a personal history of the twentieth-century. Rather than pursuing his dream of studying horticulture after graduating from high school, Green “went to a world war instead.” Abroad, he “met his future wife,” married her after the war, and “had kids, way more grandkids, and a great-grandkid,” a.k.a. the narrator. As the boy strolls through his great-grandfather’s life, gathering items that his grandfather misplaced, the physical absence of Grandpa Green gestures towards his inevitable status as memory – which, as we learn in the beautiful dénouement, is the function of the garden. Grandpa forgets things, but “the important stuff, the garden remembers for him.”

There are other children’s books about aging and loss – notably Dr. Seuss’s satiric You’re Only Old Once! (1986) and John Burningham’s gentle Granpa (1984) – but Grandpa Green is closest to Crockett Johnson’s posthumously published Magic Beach (2005). It’s slightly mysterious, with a light tone that keeps melancholy mostly at bay. Grandpa Green is a book that stays with you, as do all whom we have loved and lost.

Myra from GatheringBooks

Philip Nel