We saw Hamilton at the Saturday matinee, and several people have asked for a review. So,… here are a few thoughts on being in the room where it happens.

We saw Hamilton at the Saturday matinee, and several people have asked for a review. So,… here are a few thoughts on being in the room where it happens.

I Can’t Believe We’re Here with Him

I don’t remember when I’ve ever been so excited to see a show – any show, of any kind. Sitting in the audience before it started, I felt like a teenage girl, waiting to see her favorite band. I say that not as a slight against teenage girls, but rather as a testament to the sincerity and enthusiasm of their fandom. Since it was a matinee, I had not expected Lin-Mañuel Miranda to be performing the role of Hamilton. When I noticed that not only would he be performing, but so would Leslie Odom Jr. (Aaron Burr), Daveed Diggs (Lafayette/Jefferson), Chris Jackson (Washington), and Renée Elise Goldsberry (Angelica),… my eyes went wide. I would be seeing almost the entire original cast. Live. In a few minutes’ time! (“Almost” because Jonathan Groff is no longer King George, and Andrew Chappelle played John Laurens/Philip Hamilton.)

Just before the show starts, King George (now played by Rory O’Malley) announces – unseen, via the theatre’s speakers – that people should turn off their cell phones, not take photos, etc. Then he invites you to enjoy his show. The audience laughs.

And then,… the opening chords, as Leslie Odom Jr. walks on stage, we applaud, and it begins. “How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman….” About halfway through the song, while I was lip-syncing along, he made eye contact with me (as he was singing/rapping the very words I was lip-syncing), and his eyes yielded a hint of a smile. That’s part of the thrill of live theatre. You’re all in the room where it happens, together. The audience and the performers share the experience. Being very close to the stage (center orchestra, just six rows back) made us feel even closer.

Having listened to the cast recording and seen photographs and video clips, I arrived with an imaginary performance in my head. In that version, the stage was much larger. Sitting in the Richard Rodgers Theatre, I realized the stage is actually more compact and intimate. An enormous amount happens in a relatively small space – and quickly. The show itself compresses so much – history, love, betrayal, time, loss, death – into just 2 hours and 45 minutes. Proximity makes what is already an intense show even more so.

You’ll Be Back

After lip-syncing to the opening number, I mostly resisted the temptation to continue doing so. Mostly. Actually, it would be more accurate to say that, as I became absorbed in the performance, I lost interest in lip-synching and wanted to experience the show. To be in the moment (“this is not a moment; it’s the movement”). My focus gravitated to the center of the action, but I would love to see Hamilton multiple times so that I could focus on different areas each time. It would be great to watch just the company, dancing. And then attend another show, during which you focus only on one actor’s performance. Or see it once attending primarily to the costumes and choreography. Or view it while considering the ways in which the set of wooden beams, bricks and rope frames the action of each scene. It’s beautifully staged, costumed, performed, orchestrated. There’s so much to take in.

The staging brought out nuances and jokes I didn’t get when listening to the cast recording. As “My Shot” begins, Lafayette, Laurens, and Mulligan regard Hamilton doubtfully. As his skills as an MC win them over, their facial expressions change from uncertain to impressed. During the opening of Act II, the expressions on Madison’s and Washington’s faces convey skepticism towards the flamboyant Jefferson. Near the end of that number, Washington and Hamilton exchange a look that seems to say, “Who is this guy?”  Oh, and of course, actually seeing “Stay Alive (Reprise)” as Eliza and Hamilton share their son Philip’s last moments, and the moment of “forgiveness (can you imagine?)” in “It’s Quiet Uptown” are emotionally wrenching. I thought I would cry during “It’s Quiet Uptown,” but didn’t realize that I’d also be crying during “Stay Alive (Reprise)” and “The World Was Wide Enough.”

The staging brought out nuances and jokes I didn’t get when listening to the cast recording. As “My Shot” begins, Lafayette, Laurens, and Mulligan regard Hamilton doubtfully. As his skills as an MC win them over, their facial expressions change from uncertain to impressed. During the opening of Act II, the expressions on Madison’s and Washington’s faces convey skepticism towards the flamboyant Jefferson. Near the end of that number, Washington and Hamilton exchange a look that seems to say, “Who is this guy?”  Oh, and of course, actually seeing “Stay Alive (Reprise)” as Eliza and Hamilton share their son Philip’s last moments, and the moment of “forgiveness (can you imagine?)” in “It’s Quiet Uptown” are emotionally wrenching. I thought I would cry during “It’s Quiet Uptown,” but didn’t realize that I’d also be crying during “Stay Alive (Reprise)” and “The World Was Wide Enough.”

I also didn’t remember how funny the show is. While we’re wiping our eyes with our handkerchiefs following “It’s Quiet Uptown,” Jefferson says, “Can we get back to politics?” Madison – dabbing his eyes with his own handkerchief – says, his voice cracking, “Please?” In performance, the handkerchief gesture made this moment a hilarious meta-comment on what we had all just experienced. We laughed! After having been brought so low in the previous song, laughter was such a relief. Earlier, during “The Schuyler Sisters,” I hadn’t realized how playful Burr and Angelica were. On the recording, I took “Burr, you disgust me” as a slam – which it is. But, on stage, they’re dancing, and Burr smiles as he gives his retort, and then keeps smiling she responds. It’s a more joyous moment than I’d imagined.

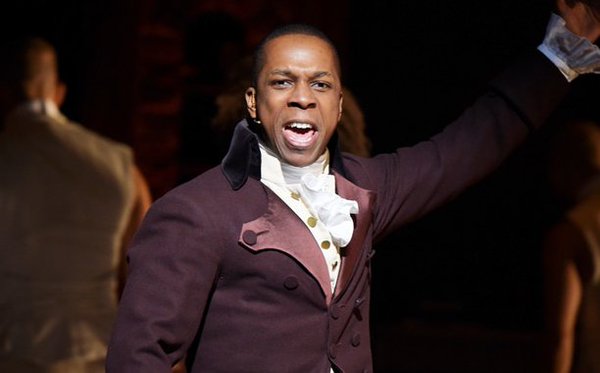

I knew the Tony Award-winning actors Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry would be amazing, but I did not realize how fantastic their fellow Tony Award-winning cast-mate Daveed Diggs would be. His serious but playful Lafayette, rapid-fire rapping with a French accent, seems the de facto leader of the revolutionaries until Washington’s arrival.  His flamboyant, narcissistic, but politically savvy Jefferson is brilliant. Diggs’ Jefferson is also non-stop, high-stepping across the stage in his purple velvet coattails.

I knew the Tony Award-winning actors Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry would be amazing, but I did not realize how fantastic their fellow Tony Award-winning cast-mate Daveed Diggs would be. His serious but playful Lafayette, rapid-fire rapping with a French accent, seems the de facto leader of the revolutionaries until Washington’s arrival.  His flamboyant, narcissistic, but politically savvy Jefferson is brilliant. Diggs’ Jefferson is also non-stop, high-stepping across the stage in his purple velvet coattails.

Look Around, Look Around

There’s something about seeing Hamilton right now, in New York, with (most of) the original cast. Beyond the sheer thrill of seeing it, most of the musical takes place in the city where it’s being performed. As you look around (“look around, how lucky we are…”), you encounter frequent reminders of the history dramatized by Miranda’s play. Walking towards Washington Square Park, we crossed both Lafayette Street (“Everyone give it up for America’s favorite fighting Frenchman!”) and Mercer Street (“The Mercer legacy is secure”). We happened upon the New York Public Library’s small, free exhibit on Alexander Hamilton, displaying the Reynolds Pamphlet (1797),“Phocion” no. 26 (1796 essay critical of Jefferson, notably his hypocrisy on slavery), The Farmer Refuted (1775), Federalist essays 12 and 13 as they originally appeared in the Daily Advertiser (1787), and letters by Hamilton. As befits a man who trained as a clerk, his handwriting is precise and legible.

There’s something about seeing Hamilton right now, in New York, with (most of) the original cast. Beyond the sheer thrill of seeing it, most of the musical takes place in the city where it’s being performed. As you look around (“look around, how lucky we are…”), you encounter frequent reminders of the history dramatized by Miranda’s play. Walking towards Washington Square Park, we crossed both Lafayette Street (“Everyone give it up for America’s favorite fighting Frenchman!”) and Mercer Street (“The Mercer legacy is secure”). We happened upon the New York Public Library’s small, free exhibit on Alexander Hamilton, displaying the Reynolds Pamphlet (1797),“Phocion” no. 26 (1796 essay critical of Jefferson, notably his hypocrisy on slavery), The Farmer Refuted (1775), Federalist essays 12 and 13 as they originally appeared in the Daily Advertiser (1787), and letters by Hamilton. As befits a man who trained as a clerk, his handwriting is precise and legible.

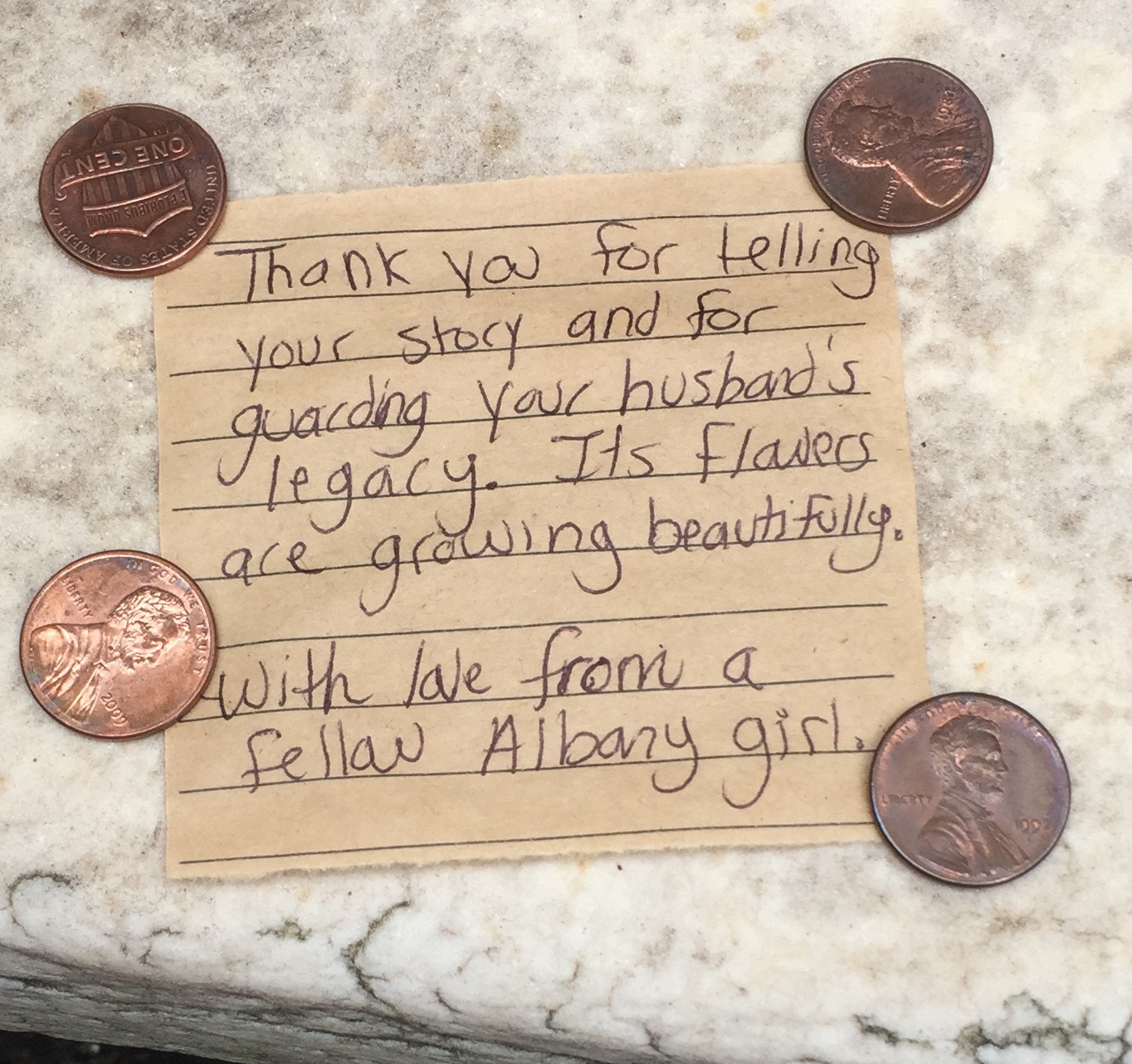

The graves of Alexander Hamilton and Elizabeth Hamilton are unaccountably moving. On the day after the show, we visited the graveyard of Trinity Church.1 I did not expect to be tearing up. But I was. Somehow, confronting these slabs of stone felt like experiencing their deaths again.  Hamilton died 212 years ago this month. He was only 47 –Â the same age as I am. Sure enough, next to the Alexander Hamilton monument is a large, flat stone for Eliza. She died 162 years ago this November. Well-wishers have scattered coins on his monument and her stone. One woman –Â I imagine a young woman, though I don’t know –Â left a note for Eliza. “Thank you for telling your story and for guarding your husband’s legacy. Its flowers are growing beautifully.” She signed herself “with love from a fellow Albany girl.”

Hamilton died 212 years ago this month. He was only 47 –Â the same age as I am. Sure enough, next to the Alexander Hamilton monument is a large, flat stone for Eliza. She died 162 years ago this November. Well-wishers have scattered coins on his monument and her stone. One woman –Â I imagine a young woman, though I don’t know –Â left a note for Eliza. “Thank you for telling your story and for guarding your husband’s legacy. Its flowers are growing beautifully.” She signed herself “with love from a fellow Albany girl.”

Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story

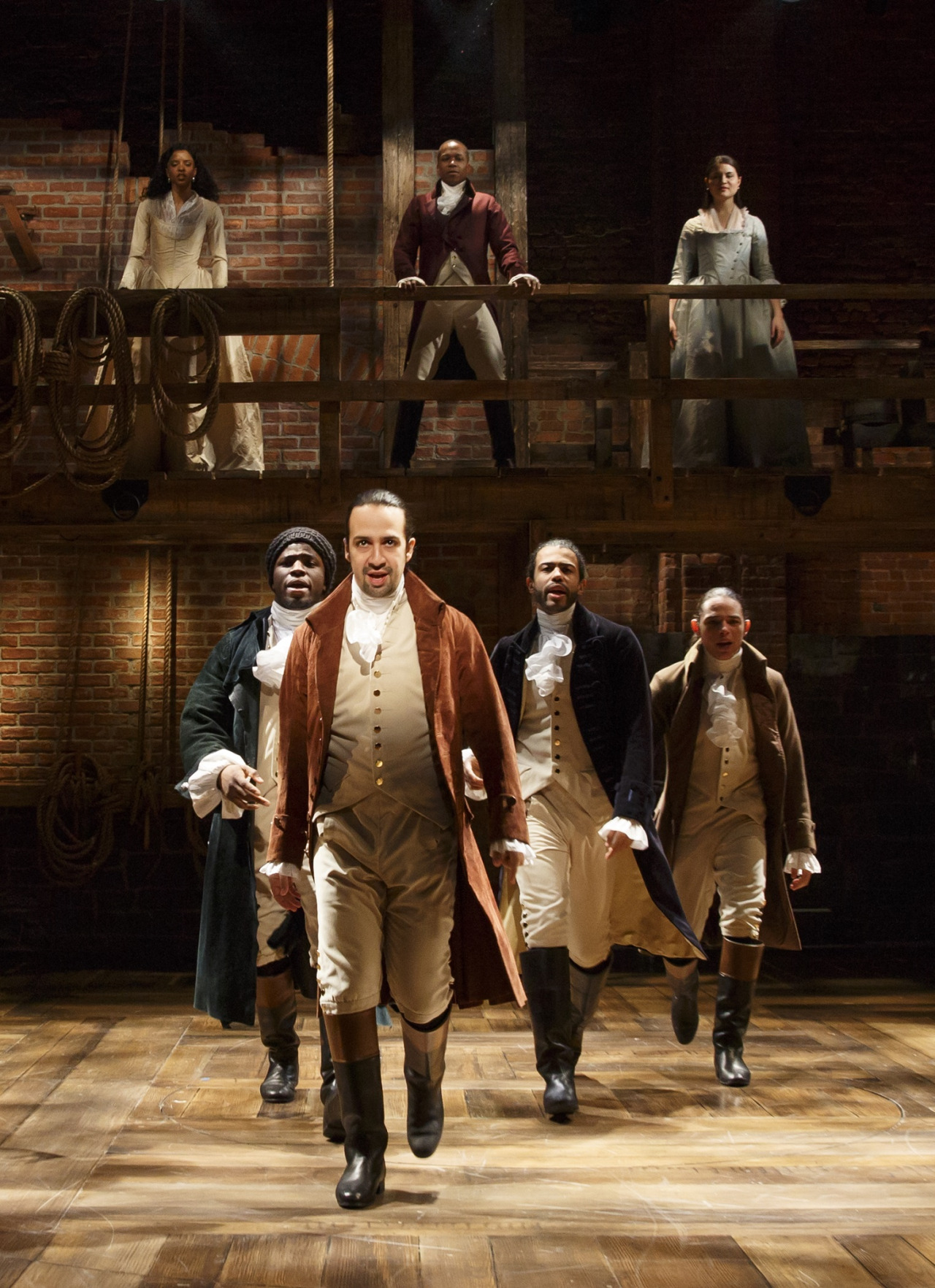

NEW YORK, NY – AUGUST 06: Cast of Hamilton perform at “Hamilton” Broadway Opening Night at Richard Rodgers Theatre on August 6, 2015 in New York City. (Photo by Neilson Barnard/Getty Images)

Back at the show, the moment the final number concluded, the audience rose as one, applauding and cheering as tears rolled down our cheeks. The entire cast lined up to do a curtain call together in a single line. They did not (as often happens) have the supporting cast take a bow first, followed by those with increasingly larger parts. Underscoring the collective nature of this endeavor, they took their bows as one –Â after which, as casts typically do, they gestured to the pit and invited us to applaud the orchestra. We did. The house lights came up. I wanted to linger, but reluctantly exited with the departing crowd.

Others have had far more intelligent things to say about the show’s cross-racial casting, use of history, elision of historical people of color,2 gender politics, cross-pollination of Broadway and hip-hop traditions. Hamilton will continue to inspire criticism to match the phenomenon. I expect books are already being written, essay collections being edited, special issues of journals assembled. I love musicals and have read Ron Chernow’s Hamilton biography, but I’m no scholar of musical theatre, nor of early American history and culture. I of course enjoy the allusions to 1776 and Grandmaster Flash, to Les Mis and Mobb Deep. The tunes are catchy, the lyrics are clever, the story is engrossing.

Others have had far more intelligent things to say about the show’s cross-racial casting, use of history, elision of historical people of color,2 gender politics, cross-pollination of Broadway and hip-hop traditions. Hamilton will continue to inspire criticism to match the phenomenon. I expect books are already being written, essay collections being edited, special issues of journals assembled. I love musicals and have read Ron Chernow’s Hamilton biography, but I’m no scholar of musical theatre, nor of early American history and culture. I of course enjoy the allusions to 1776 and Grandmaster Flash, to Les Mis and Mobb Deep. The tunes are catchy, the lyrics are clever, the story is engrossing.

Unsurprisingly to those who know me, I also identify with Hamilton. I write like I’m running out of time because I’m acutely aware that I am running out of time. I will die before I have learned, written, seen, understood, done all I would like to. Unlike Hamilton, I have no heirs. If I “build something that’s gonna outlive me,” that something will be words and ideas. Have I written these yet? I can’t and will never know. I do know, however, that in my pursuit of that elusive something, I can be “a polymath, a pain in the ass, a massive pain.” Thankfully, my friends and colleagues manage to put up with me anyway. Thankfully, also, I’ve been fortunate to publish some of my ideas, collaborate with smart people, and continue on my impossible quest.

On that note, and to quote a line not on the cast recording, “I have so much work to do.”3

Notes

- Located at the intersection of Wall Street and Broadway, Trinity Church is the appropriate resting place for a founder of America’s financial system who is currently being celebrated on New York’s stage.

- When, during “What’d I Miss?” Jefferson says, “Sally, be a lamb, darling” to a member of the company, she becomes –Â for that moment –Â Sally Hemmings. I think she is thus the only historical person of color we see on stage. But more astute viewers of Hamilton should correct me if I am wrong.

- The show includes one scene not on the cast recording. The Hamiltons receive a letter from John Laurens’ father, reporting the death of his son –Â Hamilton’s friend. Eliza reads it to her husband. He’s silent. She asks if he’s OK. His voice choked with emotion, Hamilton says the line “I have so much work to do.”

Photos

I took the ones of the Hamilton marquee, empty stage, NYPL banner, gravesite and note. All other photos found elsewhere on the web. Â For example, you’re not allowed to take photos during the performance; these were done specially, with the cooperation of the cast.

Monica Edinger

Julia

Deborah Taylor

Philip Nel

Julia Mickenberg

Philip Nel

Marah Gubar

Philip Nel

Nicolette

Philip Nel