I remember when I fell into the work of Paul Auster. Because that’s also when I fell for his books.

After reading City of Glass (1985) in my Honors English class in the fall of 1991, I then read the other two books in his New York Trilogy: Ghosts (1986) and The Locked Room (1986). With the narrative urgency of a detective novel and prose that had the precision of poetry, the books were mysteries that, because they were about life itself, are ultimately unsolvable. Or the promised solutions turned out to be the deeper understanding you gained during the process of reading them.

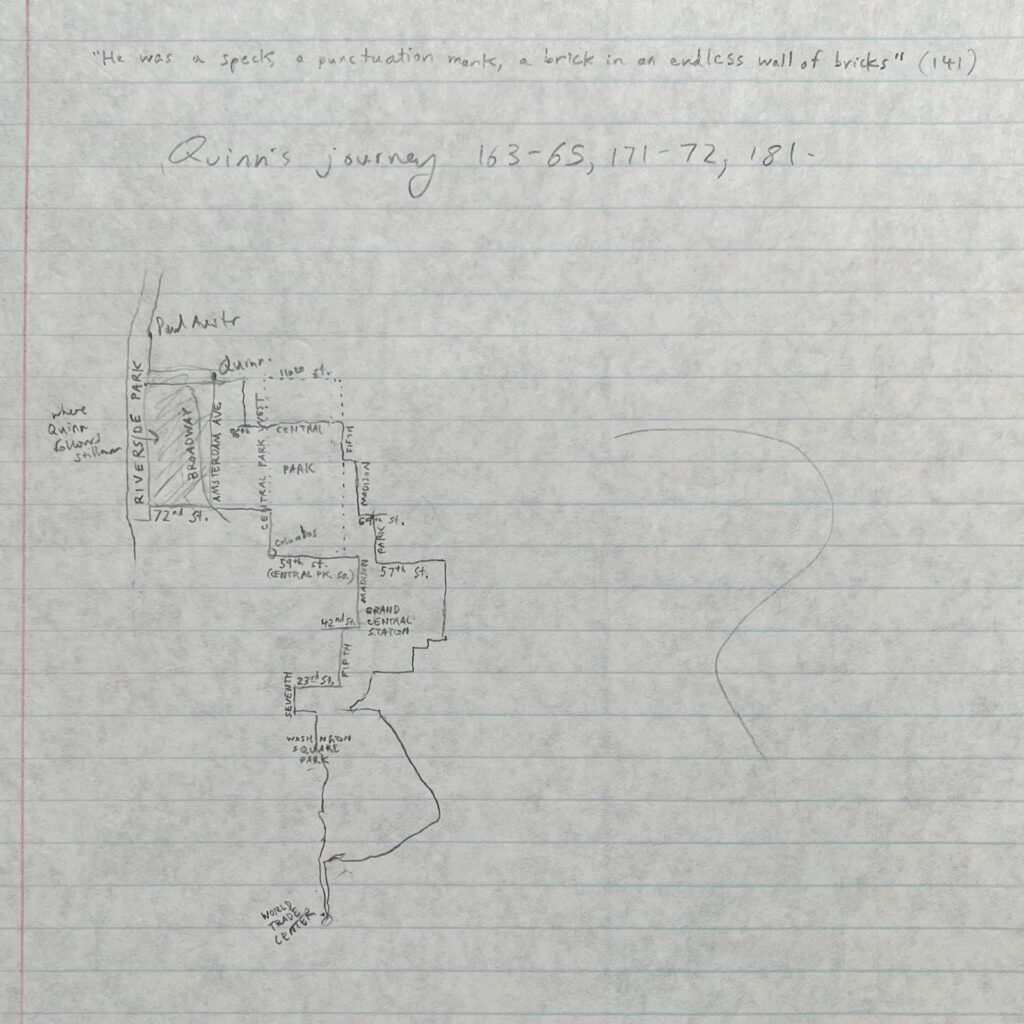

Not yet fully grasping that fact, perhaps, I mapped the journey of City of Glass protagonist Quinn… revealing only a “?”

Earlier in the novel, Quinn — pretending to be a detective named Paul Auster — follows through the streets of NYC a man who may or may not be Peter Stillman. Tracing each daily journey on a map, Quinn discovers that they spell a clue (which I won’t reveal here). In drawing my own map, I imagined I might find a similar clue. And perhaps I did. Or maybe not.

Continuing my quest, I also read Auster’s The Music of Solitude — a memoir that (it seemed to me at the time) was a sort of ur-text for The New York Trilogy. I wrote my paper on all four of these works.

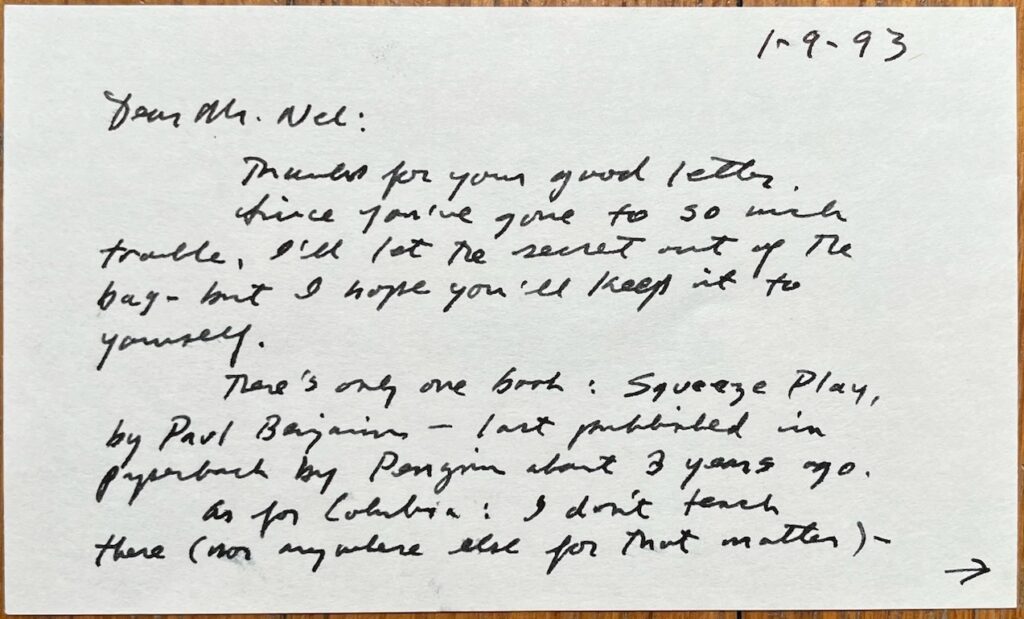

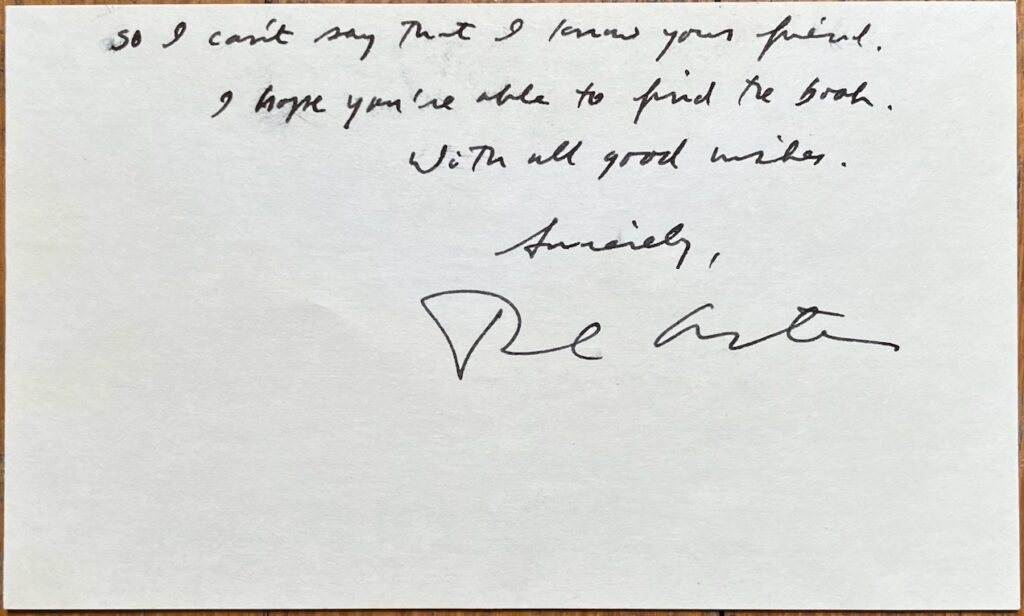

After the class ended, I sought other Auster work, including a pseudonymous detective novel. Since I could discover neither the novel’s title nor the pseudonym, I wrote to Mr. Auster himself. Optimistically, I included a self-addressed stamped envelope. To my surprise and delight, he sent his response via that envelope.

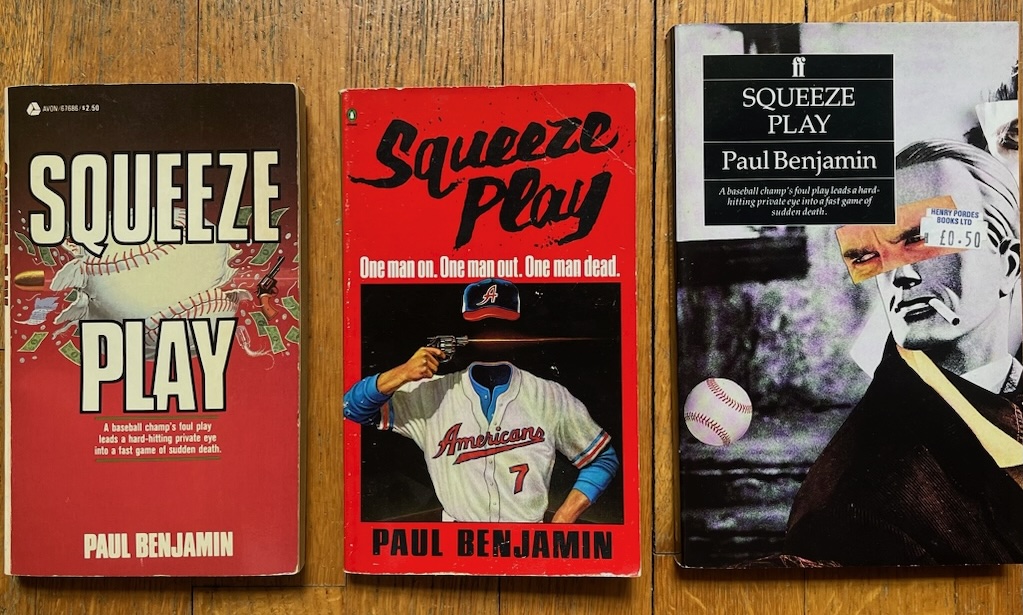

I didn’t reveal his secret, and I don’t even know how much of a secret it was. But I did buy a copy of the novel and, then, whenever in a bookstore, I would just keep an eye out for it. I ended up with more than one copy — a fact which I recalled a couple of weeks ago, reading an Auster-themed Facebook post by my pal Cam Ostrin, whom I met in that English class. Well, no, not met. We’d been acquainted before, but we really became friends in that class.

Turns out I actually have three copies. I’m sending one to Cam.

I say “turns out” because I only just returned home. I learned of his death on the train from Charles de Gaulle Airport to Rouen. Appropriate, perhaps. The French have long considered Paul Auster one of America’s greatest novelists. And his European reputation has always eclipsed his American reputation.

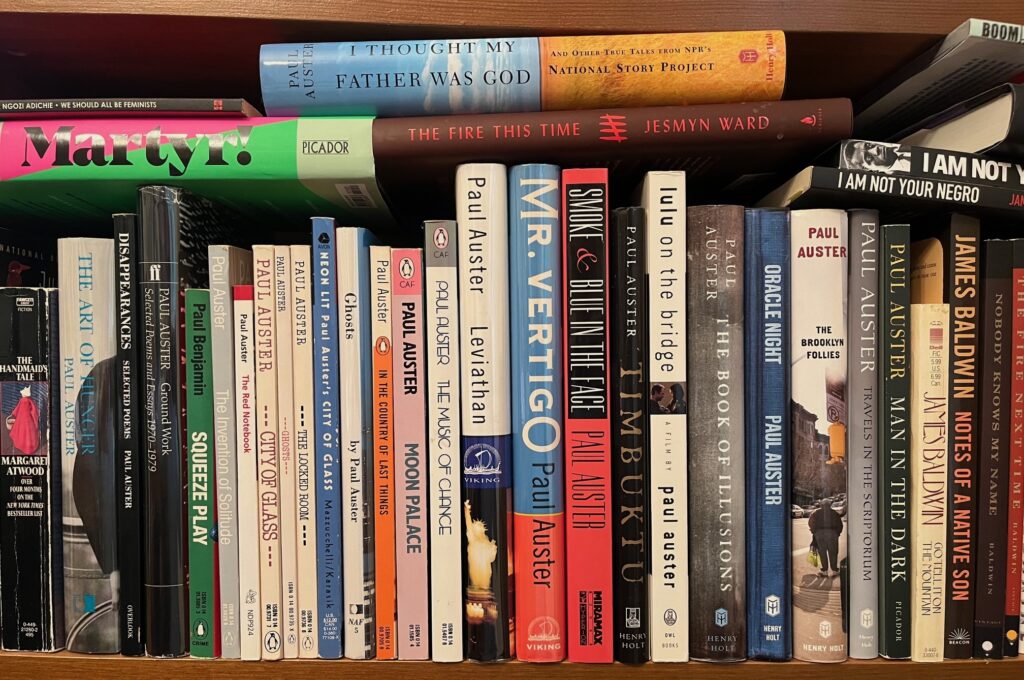

Anyway, now at home, I am looking at my Auster novels and my Auster folder — of articles, notes, interviews, and of course the note from Auster himself. I began compiling the folder as an undergraduate and, though I stopped adding to it maybe 25 years ago, I kept up with his work, buying and reading each new book or (in the case of a film) seeing the movie. Or, at least, I kept up until Man in the Dark (2008). I’m not quite sure why that was the last one. He’s written five more novels since.

Well, to quote the final lines of one of his books (though I won’t say which, because I don’t want to spoil anything), “It was. It never will be again. Remember.”

And to paraphrase the ending of another:

Sleep well, Mr. Auster.

Lights out.

Eric Wybenga

Philip Nel

Eric Wybenga

Lia Vella

Philip Nel

Eric Wybenga

Philip Nel

Carlos Zigel