Composer/producer/musician Jon Brion distinguishes between songs and performance pieces. What’s the difference? In a 2006 episode of Sound Opinions (rebroadcast in a 2012 episode of 99% Invisible), he cites Led Zeppelin as an example of the latter. Though he’s “a big fan” of Zeppelin, their songs “are the ultimate performance pieces.” He explains,

And the way I can sort of prove my point is: have you ever listened to anybody else play a Led Zeppelin song and gone “Oh, that was a great satisfying experience”? Except for Dread Zeppelin, who I loved. What people like is that specific guitar sound, that specific performance, in concert with that specific drum sound, with that specific drummer playing that specific part.

Another example of the performance piece, Brion says, is most punk rock.

In contrast, a song stands on its own, separate from any individual performance. As examples of that, he cites George Gershwin, Kurt Cobain, Thom Yorke, and Thelonious Monk. In the interview, which I’ve excerpted below (and to which you should listen), he demonstrates his point by playing songs on the piano – including a lovely arrangement of a few bars from Nirvana’s “Lithium.”

His distinction between songs and performance pieces is a really useful way of thinking about different types of music. However, like all such paradigms, the more you look at it, the more the boundaries between songs and performance pieces start to blur. For example, a key marker for Brion is the cover version. As he says, you could play a Gershwin song “in the style of Led Zeppelin, and have a completely satisfying experience,” but “when you start playing Zeppelin songs, say, in the style of, like, 1920s music, suddenly it’s laid bare that, oh no, it was about those people, and those people were in a room, and it was great.”

There are two flaws in that otherwise compelling argument. First, there are great covers of Zeppelin, and of punk. Bonerama does a fantastic version of “The Ocean” (2007). You listen to it and think: why didn’t Zeppelin ever tour with a trombone section? (Or, at least, this is what I think when I listen to it.) Dolly Parton does a lovely bluegrass cover of “Stairway to Heaven” (2002). And then there’s Johnny Favourite Swing Orchestra’s swing version of “Black Dog” (1999)

Bonerama’s “The Ocean” (2007)

Dolly Parton’s “Stairway to Heaven” (2002)

Johnny Favourite Swing Orchestra’s “Black Dog” (1999)

For punk rock, I could point you to Yo La Tengo’s surf-rock-lite cover of the Ramones’ “Blitzkrieg Bop” (1976) or the Indigo Girls’ acoustic version of the Clash’s “Clampdown” (1979)

Yo La Tengo’s “Blitzkrieg Bop” (1996)

Indigo Girls’ “Clampdown” (1993)

So, if (according to Brion’s rubric) punk or Zeppelin resists the cover version, well, there seem ample examples to contradict that claim.

The second problem is that a lot of Zeppelin and a lot of punk are already cover versions. In the case of Zeppelin, they tended to take from African American artists without attribution. “Moby Dick” (1969) borrows liberally from Bobby Parker’s “Watch Your Step” (1961), “Whole Lotta Love” (1969) lifts a fair bit from Muddy Waters’ version of “You Need Love” (1963, a cover of Willie Dixon). And those are just a few examples.

Bobby Parker’s “Watch Your Step” (1961)

Led Zeppelin’s “Moby Dick” (1969)

Muddy Waters’ “You Need Love” (1962)

Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love” (1969)

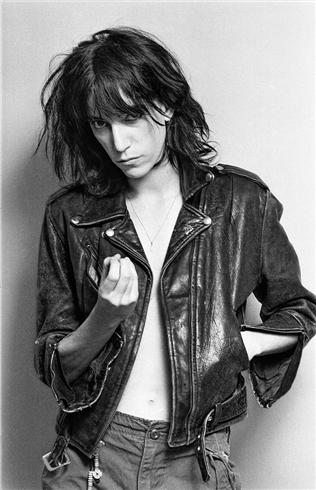

Some of the most famous punk songs are covers – the Clash’s “I Fought the Law” (1979) and Patti Smith’s “My Generation” (1976). The latter is a cover of the Who, and the former a cover of the Bobby Fuller Four (who were covering Sonny Curtis & the Crickets).

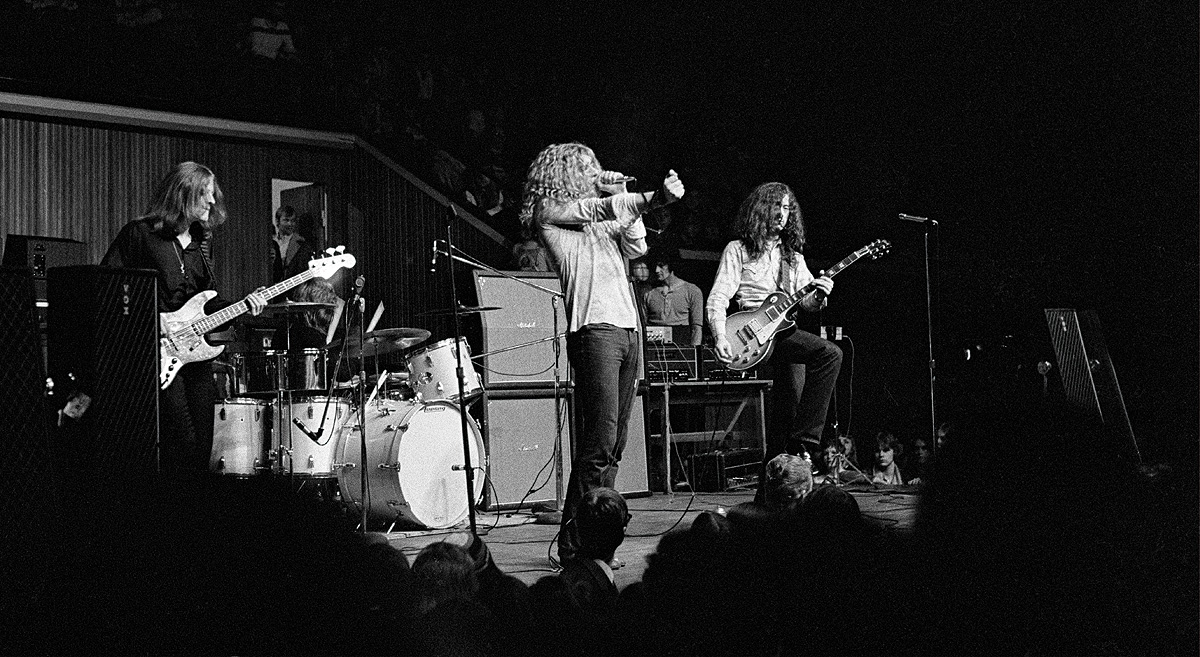

The Clash, performing in London, 1979

Patti Smith Group, performing in Germany, 1979

In sum, the line between song (which can be covered) and performance (which cannot) seems blurrier than Brion’s distinction admits.

I don’t think his distinction lacks utility, though. As a connoisseur of covers, I would add – in defense of his argument – that there are far fewer good covers of Zeppelin than there are of Nirvana or Radiohead. In this sense, we might see my examples above as exceptions to the rule. Similarly, what’s punk about Patti Smith’s cover of the Who is her performance. You can do a good cover of the Who’s version, but you can’t do a good cover of Patti Smith’s version. The only way to cover of Patti Smith’s version would be as a Patti Smith tribute band, a mere imitation of the original. (In my view, by definition, a good cover brings forth a facet of the song that the original version does not. In their attempts to be faithful, tribute bands don’t meet this standard.)

I don’t think his distinction lacks utility, though. As a connoisseur of covers, I would add – in defense of his argument – that there are far fewer good covers of Zeppelin than there are of Nirvana or Radiohead. In this sense, we might see my examples above as exceptions to the rule. Similarly, what’s punk about Patti Smith’s cover of the Who is her performance. You can do a good cover of the Who’s version, but you can’t do a good cover of Patti Smith’s version. The only way to cover of Patti Smith’s version would be as a Patti Smith tribute band, a mere imitation of the original. (In my view, by definition, a good cover brings forth a facet of the song that the original version does not. In their attempts to be faithful, tribute bands don’t meet this standard.)

Brion’s song-vs.-performance-piece distinction is handy, even if it’s not quite the paradigm that it at first seems. That is, his idea is useful less for distinguishing songs from performances and more for giving us a way of thinking about musical taste.

Ultimately, that’s what his distinction highlights: Jon Brion prefers Gershwin and Cobain to, say, Page, Plant, and Ramones. His too-frequent mentions of his alleged “love” for Led Zeppelin are him protesting too much, giving him rhetorical cover for saying that Led Zeppelin didn’t write songs. And yet, even while his rubric is just disguising personal preference in the language of objectivity, this is one key function of criticism. We find formal terms to talk about what moves us, or fails to move us. Or, to put this another way, we need to find these terms in order to have a conversation with people whose likes and dislikes differ from our own.

Ultimately, that’s what his distinction highlights: Jon Brion prefers Gershwin and Cobain to, say, Page, Plant, and Ramones. His too-frequent mentions of his alleged “love” for Led Zeppelin are him protesting too much, giving him rhetorical cover for saying that Led Zeppelin didn’t write songs. And yet, even while his rubric is just disguising personal preference in the language of objectivity, this is one key function of criticism. We find formal terms to talk about what moves us, or fails to move us. Or, to put this another way, we need to find these terms in order to have a conversation with people whose likes and dislikes differ from our own.

Terms like Brion’s help us talk about taste. They don’t need to be perfectly theorized to be useful.

Related posts:

- Let’s Talk About Taste (22 June 2012)

- “There Are Loads of Rules”: The Art of the Mixtape (19 July 2014)

Scott Peeples

Philip Nel