There’s a new Facebook meme: “How to determine who to unfriend on Facebook.”

Click on the link, and you get a list of “Friends who like Nickelback.”

The joke depends upon pervasive dislike of the popular Canadian band. At best, I find the group’s music benign. I could imagine it being used to sell soda or life insurance. Yet Nickelback’s massive success suggests that its fans are hearing something that I’m missing. Perhaps they hear vocalist Chad Kroeger’s raspy shout as emotional intensity, the bland homilies (“every second counts because there’s no second try / so live like you’ll never live it twice”) as profound insights, and the bombastic production as appropriately anthemic.

Or perhaps it’s more complicated. Certainly, it’s a question of taste.

In his book Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste (2007), Carl Wilson tackles this question using another Canadian megastar as his case study: Céline Dion. Most of the books in Continuum’s 33 1/3 series examine a critically important album: the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street, the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, Prince’s Sign ☮ the Times, Talking Heads’ Fear of Music, Elliott Smith’s X/O. For his entry in the series, Wilson chose Céline Dion’s Let’s Talk About Love because he wanted to answer the question of why “do each of us hate some songs, or the entire output of some musicians, that millions upon millions of other people adore?” (1). He picked her Let’s Talk About Love because it has that Titanic song on it.

In his book Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste (2007), Carl Wilson tackles this question using another Canadian megastar as his case study: Céline Dion. Most of the books in Continuum’s 33 1/3 series examine a critically important album: the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street, the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, Prince’s Sign ☮ the Times, Talking Heads’ Fear of Music, Elliott Smith’s X/O. For his entry in the series, Wilson chose Céline Dion’s Let’s Talk About Love because he wanted to answer the question of why “do each of us hate some songs, or the entire output of some musicians, that millions upon millions of other people adore?” (1). He picked her Let’s Talk About Love because it has that Titanic song on it.

And because it gives him an opportunity to create humorous chapter titles: “Let’s Talk About Hate,” “Let’s Talk About Schmaltz,” “Let’s Sing Really Loud,” and “Let’s Talk About Taste” are a few of them. A music critic for Toronto’s Globe and Mail, Wilson has a sense of humor, but the book is a serious inquiry into taste. It’s also become one of my favorite books. As anyone who has spoken to me in the last few weeks will tell you, I’ve been evangelizing it – rather as one does upon hearing a particularly wonderful piece of music. I want to share this book with everyone. If you have any interest in taste or in music, you really must read it.

The book both is and is not about Céline Dion. Wilson takes her and her work seriously, but does so as part of his larger inquiry. In “Let’s Talk in French,” he considers her Quebec roots and the province’s particular musical culture – specifically, the conflict between the chanson (the poetic, sometimes political work of “homegrown Gainsbourgs and Dylans (it was mostly guys)” that began in the 60s) and the kétaine ( “tacky” or “hickish,” pre-60s “variety-pop”) (26-27). In “Let’s Talk About Schmaltz,” he historicizes the term: Yiddish for “chicken fat,” schmaltz comes from vaudeville, and it’s not a bad thing. If a song or performance lacks schmaltz, then it’s too dry. However, if it has too much, then it’s, well, schmaltzy. But schmaltz can be about big emotions… which, of course, are what defines Céline’s music.

I especially enjoy that the book engages with questions of taste –Â and, yes, Hume, Kant, Bourdieu, & others make appearances here (Wilson has done his homework). In the twenty-first century, we don’t talk much about taste any more. As Wilson puts it, “We don’t commend someone’s good taste because we don’t want to be caught wearing morning coats and waxed mustaches and asking what the devil is up with the wogs. We don’t use bad taste except as a jocular antagonym in which bad means good” (149-150). He’s right. Making judgments on taste feels anachronistic or elitist. We’re much more likely to use “taste” in a fuzzy, laissez-faire way, dismissing (or accommodating) difference by saying “oh, it’s just different tastes” or “well, people have different tastes.”

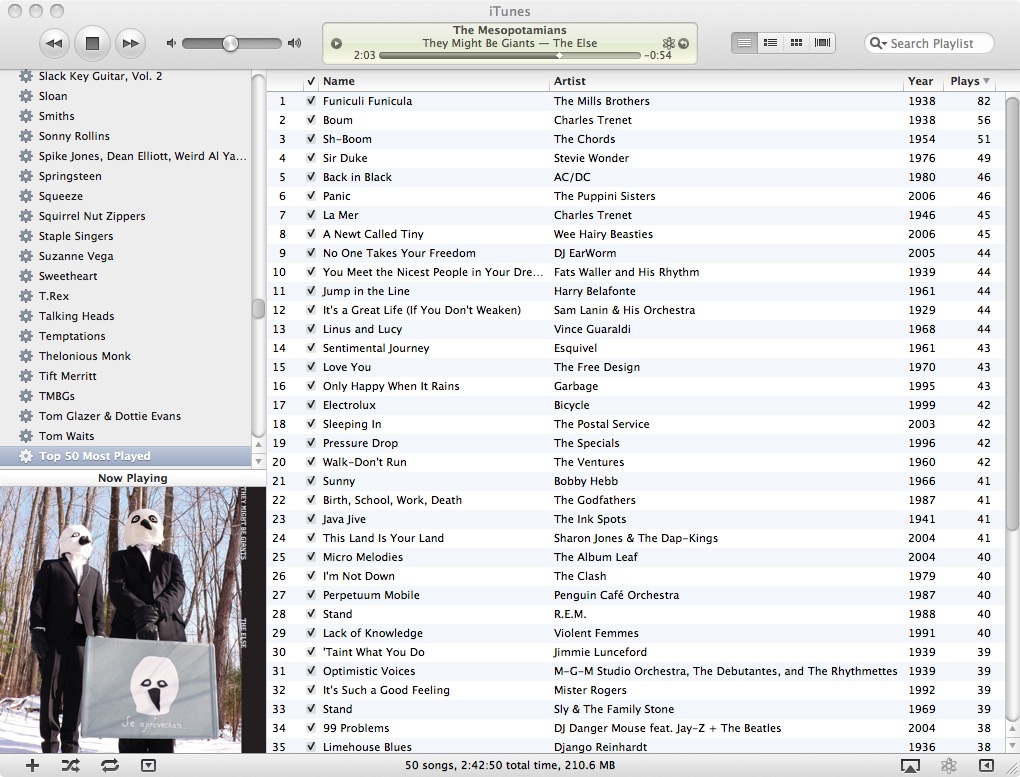

As a scholar, I’m constantly called upon to appreciate works that may not be to my taste. So, I read in terms of genre, evaluating a work as, say, an excellent example of a horror novel, or a picture book, or a poem, or a graphic novel – or, really, many genres. (It’s rare to find a work that fits only one genre.) This mode of art appreciation feels natural to me because, for as long as I’ve been listening to music, I’ve been listening to different kinds of music. The music I remember from earliest childhood includes Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Louis Armstrong, Jimmie Rodgers, and Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass.  My parents must have had !!Going Places!! (1965), because I distinctly remember Alpert and the Tijuana Brass’s version of “Walk, Don’t Run” – I knew that before I knew the Ventures’ original. By about 11 years old, I began to develop my own musical tastes: novelty records (“Weird Al” Yankovic and anything played on the Dr. Demento Show, really), the Beatles, AC/DC, ’50s rock ’n’ roll, and the J. Geils Band (this was 1981-1982). That soon expanded to encompass ’60s R&B, ’80s new wave, jazz, what is now called “classic rock” (but was then AOR), hip-hop (then known as rap), and, well, nearly any type of music. Here’s a snapshot of my “Top 50 Most Played” in iTunes – or Top 35 because that’s all that fits on the screen (click for larger image).

That’s quite representative, although it skews towards music I’ve had longer and omits the top two most-played artists in my iTunes: They Might Be Giants (292 songs, excluding covers, solo work, and podcasts), and the Beatles (194 songs, also excluding covers and solo work).

I’ve long prided myself on my eclectic tastes, but Carl Wilson has me pegged. As he says,

American sociologists Richard Petersen and Roger Kern in the mid-1990s suggested that the upper-class taste model had changed from a “snob” to an “omnivore” ideal, in which the coolest thing for a well-off and well-educated person to do is to consume some high culture along with heaps of popular culture, international art and lowbrow entertainment: a contemporary opera one evening, the roller derby and an Afrobeat show the next. They speculate that the shift corresponds to a new elite requirement to be able to “code switch” in varied cultural settings, due to multiculturalism and globalization. (96)

So, while I may think my wide-ranging tastes are democratic or open-minded, Wilson would claim that I’ve just adopted the contemporary “omnivore” ideal. In fairness, Wilson indicts himself, too: “Indeed you could fairly say that my experiment is an attempt to expand my cultural capital among music critics, to gain symbolic status by being the most omnivorous of all” (100).

I can’t think of a better or more succinct education in taste and in popular music than Wilson’s Let’s Talk About Love. It’s delightful, fun, and compact (only 164 pages). Â If you’re interested in music, you’ll enjoy it.

Even if you listen to Nickelback.

rockinlibrarian

Natalia

Philip Nel

Jenny

jules

Philip Nel

Ivan Ulz a.k.a Treasure Ivan

Philip Nel