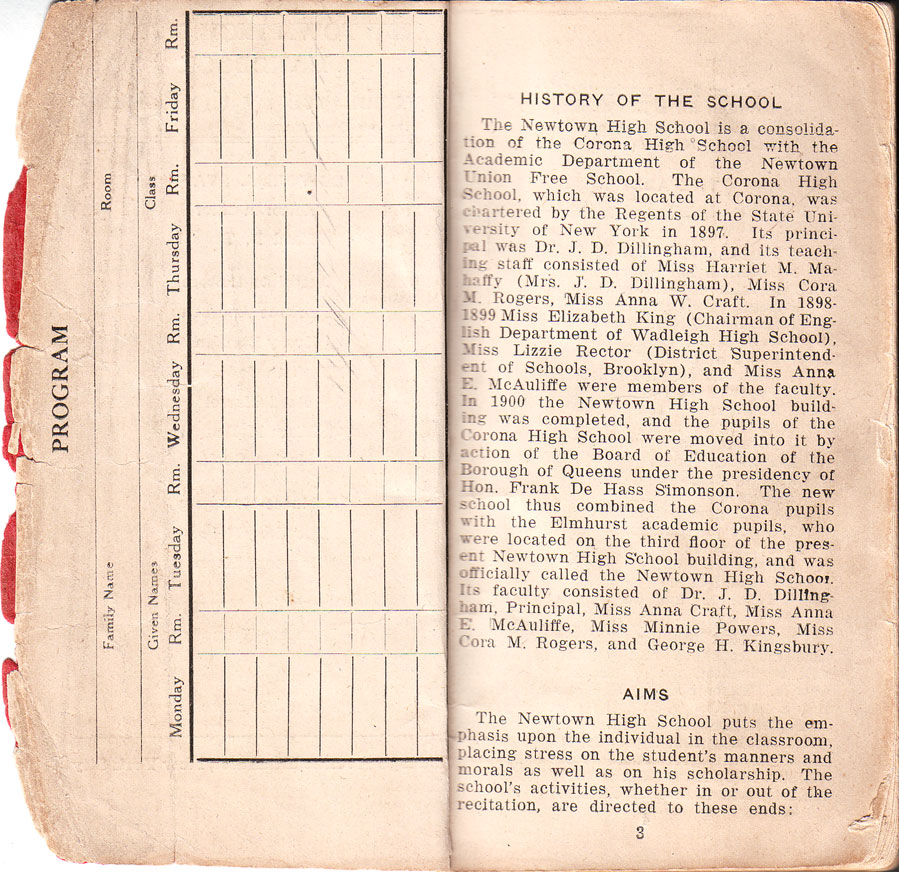

What was high school like 90 years ago? This Newtown High School Handbook provides some sense of what it was like in Newtown, Queens in 1921, when Crockett Johnson (a.k.a. David Leisk) was a student there. No yearbooks from the Newtown class of 1924 (Johnson’s graduating class) survive, but plenty of things do: The Queens Public Library’s Long Island History Division has a class of ’24 photo, and one issue of the Newtown H.S. Lantern from the period. Via eBay, I obtained other copies of the Lantern – in which you can find Crockett Johnson’s earliest cartoons (see this earlier blog post on the subject). Reading through copies of the Daily Star (the local paper) also helped.

What was high school like 90 years ago? This Newtown High School Handbook provides some sense of what it was like in Newtown, Queens in 1921, when Crockett Johnson (a.k.a. David Leisk) was a student there. No yearbooks from the Newtown class of 1924 (Johnson’s graduating class) survive, but plenty of things do: The Queens Public Library’s Long Island History Division has a class of ’24 photo, and one issue of the Newtown H.S. Lantern from the period. Via eBay, I obtained other copies of the Lantern – in which you can find Crockett Johnson’s earliest cartoons (see this earlier blog post on the subject). Reading through copies of the Daily Star (the local paper) also helped.

I had to do a lot more of this sort of work for Crockett Johnson than I did for Ruth Krauss. She wrote about herself, and attended private schools that kept records. He did not write about himself and attended public schools. The children of the wealthy leave more traces than the children of the working class. Anyway, this little book only yielded a couple of paragraphs in The Purple Crayon and a Hole to Dig: The Lives of Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss (forthcoming 2012 from the University Press of Mississippi), but it’s a fascinating document.

At 5 ½ in. (14.5 cm.) tall x 3 3/8 in. (8.5 cm.) wide x ¼ in. (7 mm.) thick, the book fits easily into a pocket – which perhaps contributed to the rounded and slightly frayed edges of my copy.

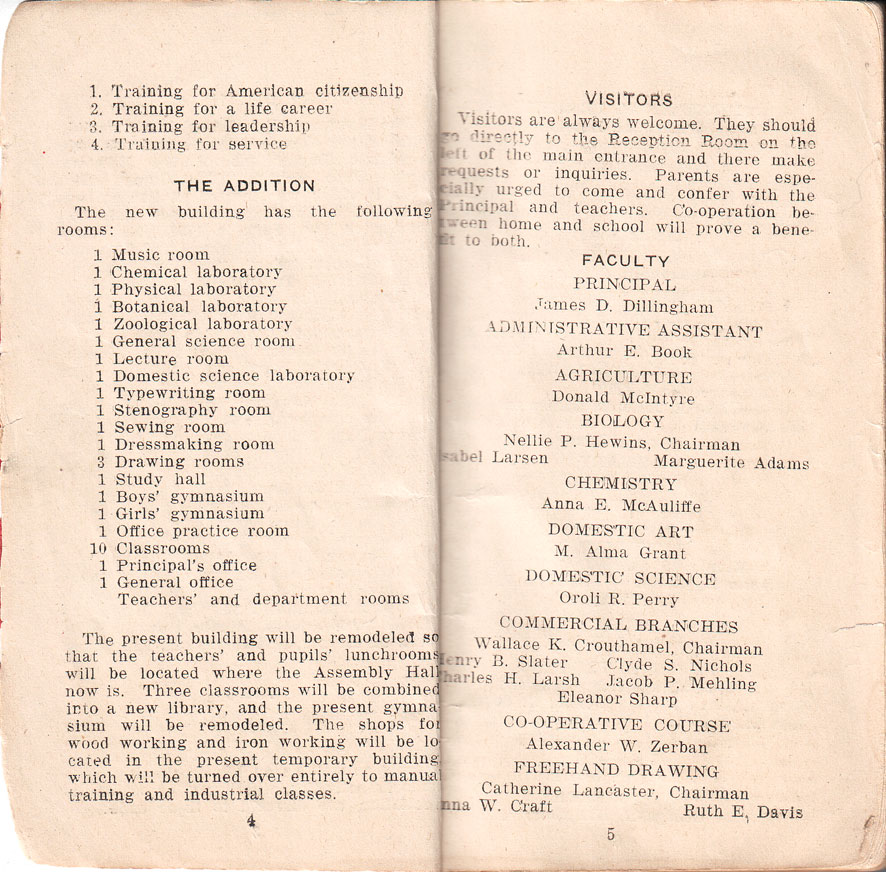

Note that the aims include “Training for American citizenship” (patriotic), “Training for a life career” (vocational), and “Training for service” (civic). I’m not sure whether Newtown High School still publishes a handbook, but the school’s website now describes it as “a school that consists of ambitious and intellectual students who are willing to do the best they can in order to accomplish their goals in life.”  That strikes me as roughly parallel to the “aims” section of the handbook.

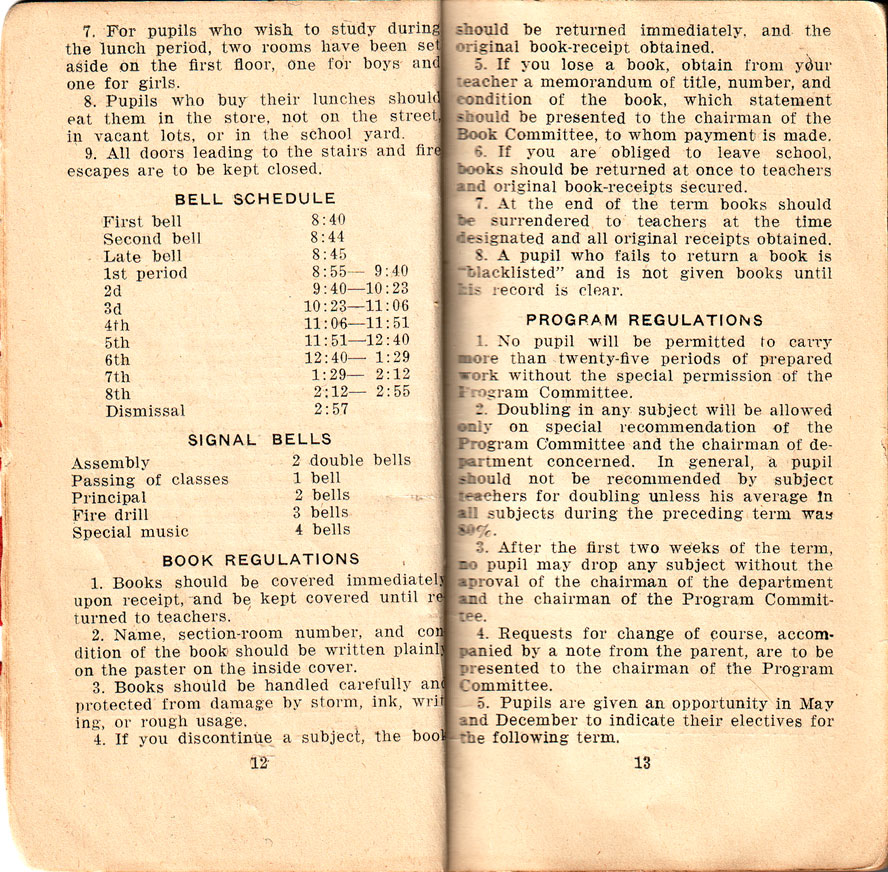

Then, the school day began at 8:55 a.m. and ended at 2:57 p.m. Now, the day begins at 7:30 a.m. and ends at 3:51 p.m. — about 1 hour and 20 minutes longer than it used to be.  So, whether education now is less rigorous than it once was (as some contend), students at Newtown do receive it for a greater period of time than they once did.

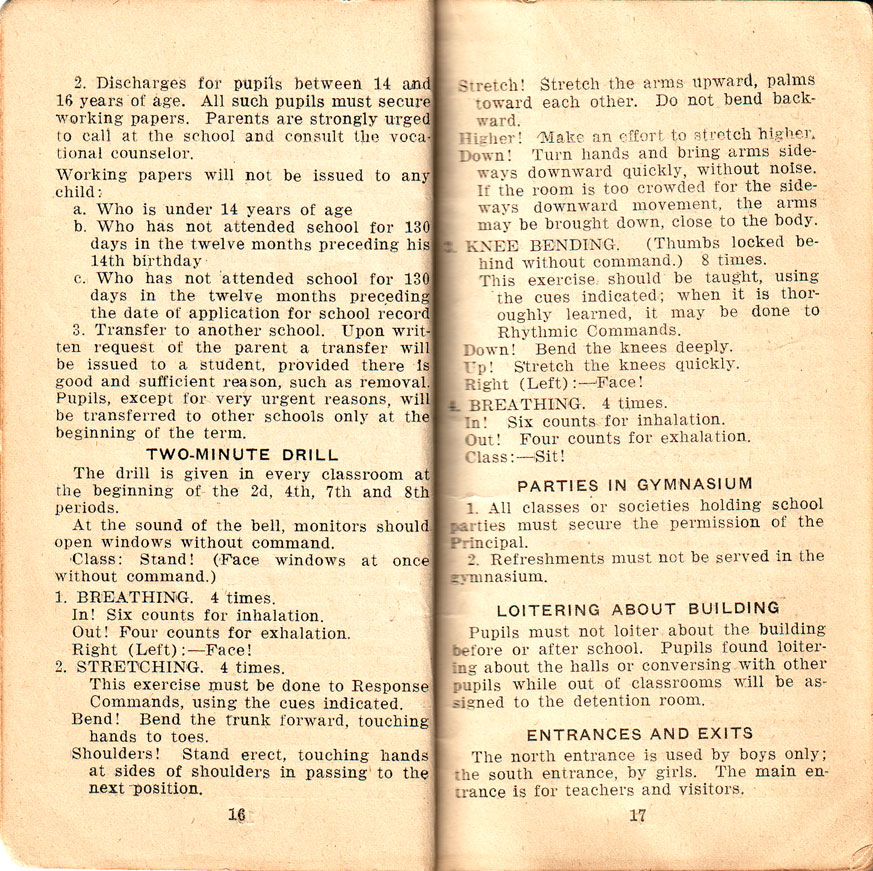

I find this inter-period exercise drill fascinating:

Also: though regimented nature of the “two-minute drill” has an oddly military flavor, a little calisthenics between periods strikes me as a promising idea. Â It would help wake students up a bit. Â I know that, as a student, I often needed a bit of waking up. Â (Since adolescence, I’ve been chronically short of sleep.)

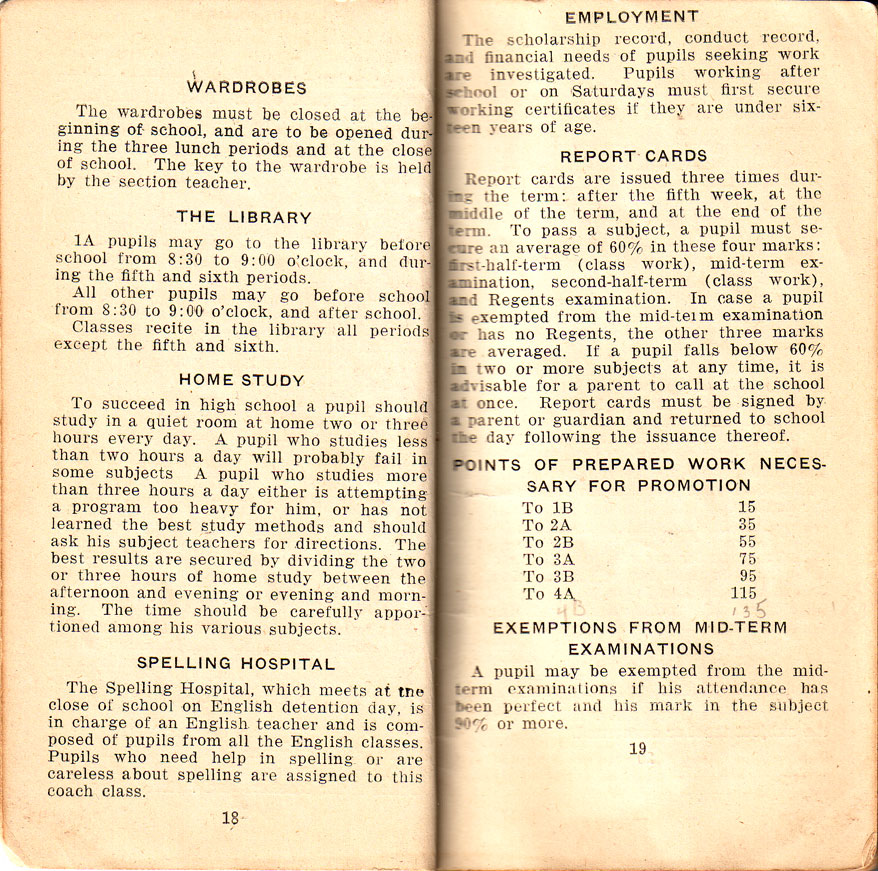

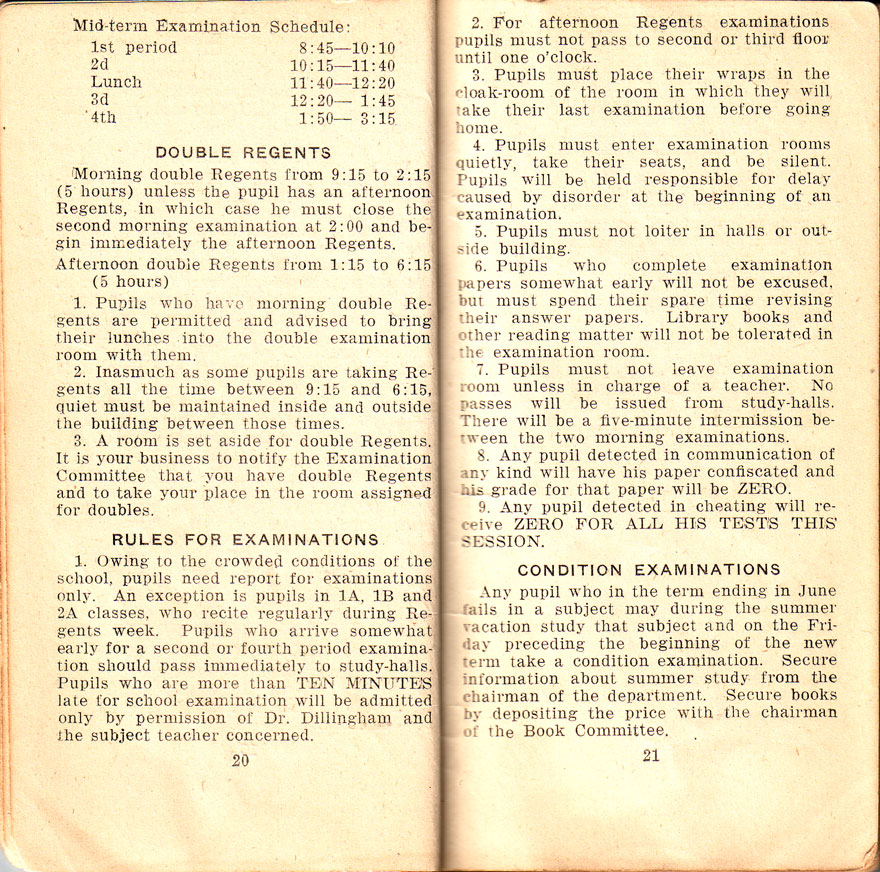

Note the expectations conveyed by “Home Study” and “Employment,” above. The handbook recommends 2-3 hours (no more, no less) of study each day. Students seeking remunerative employment “after school or on Saturdays” need to be at least 16 years old. If they are not, then they require “working certificates.” And check out the strict prohibition against cheating (below): “Any pupil detected in cheating will receive ZERO FOR ALL HIS TESTS THIS SESSION.”  They don’t mess around at Newtown.

The current Newtown High School’s rules has a prohibition against cell phones. In 1921, “The office telephone may not be used for any other than official business. Pupil will not be summoned to answer any telephone calls whatever; nor will telephone messages be delivered to pupils except in cases of extreme emergency, and then only through the principal.”

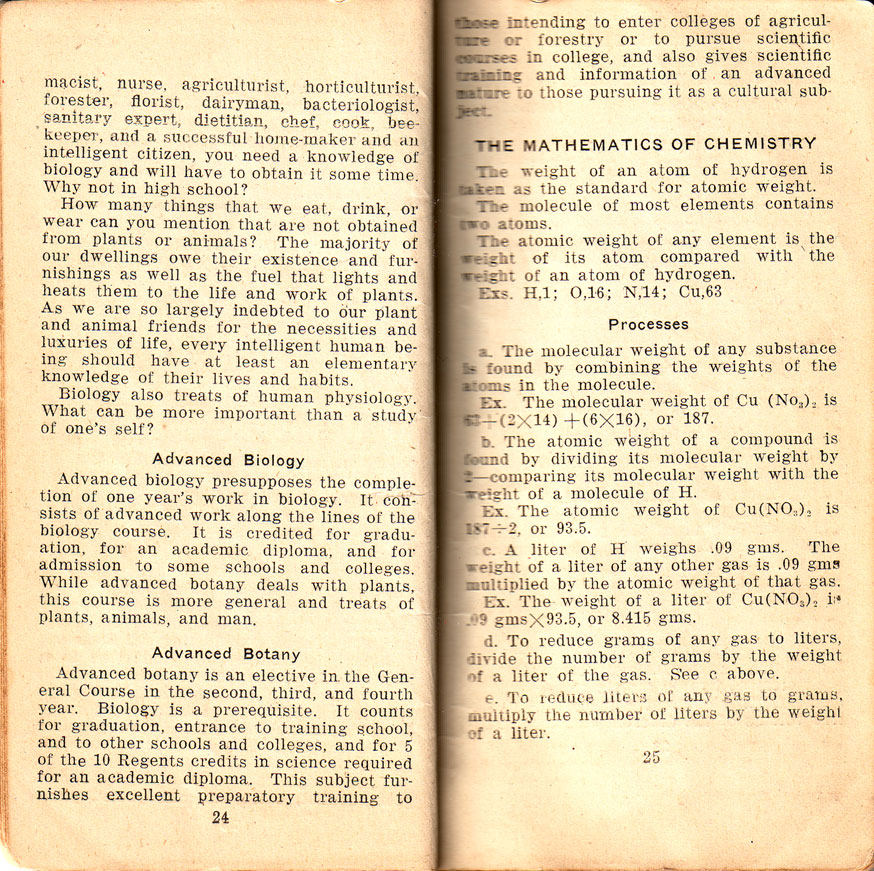

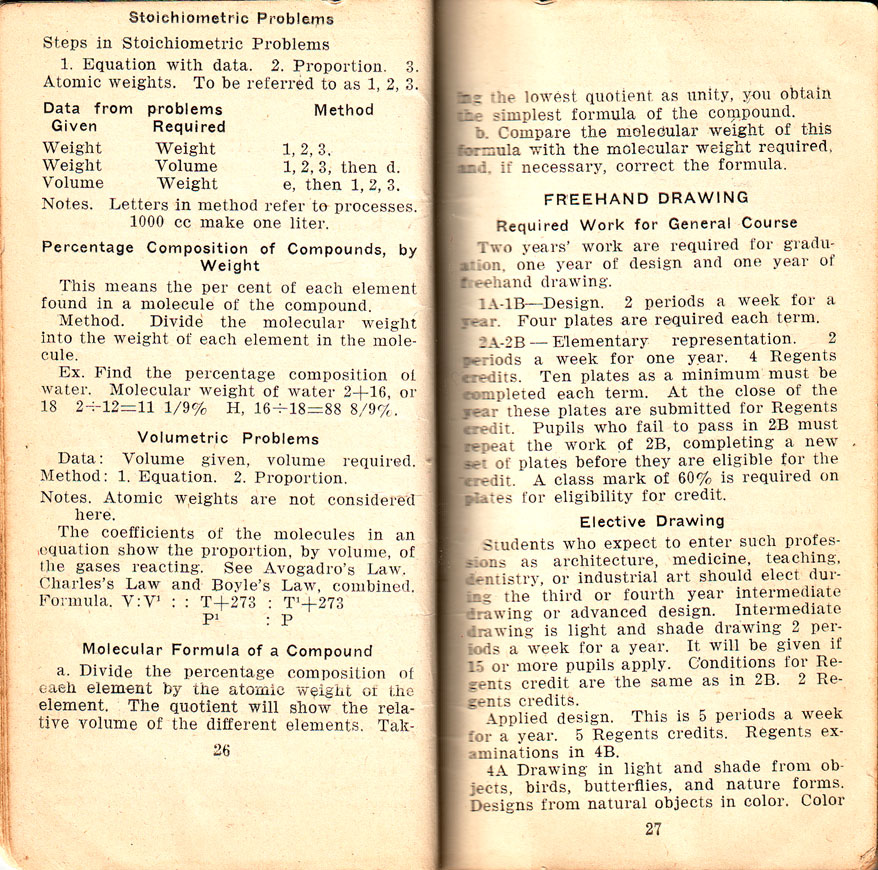

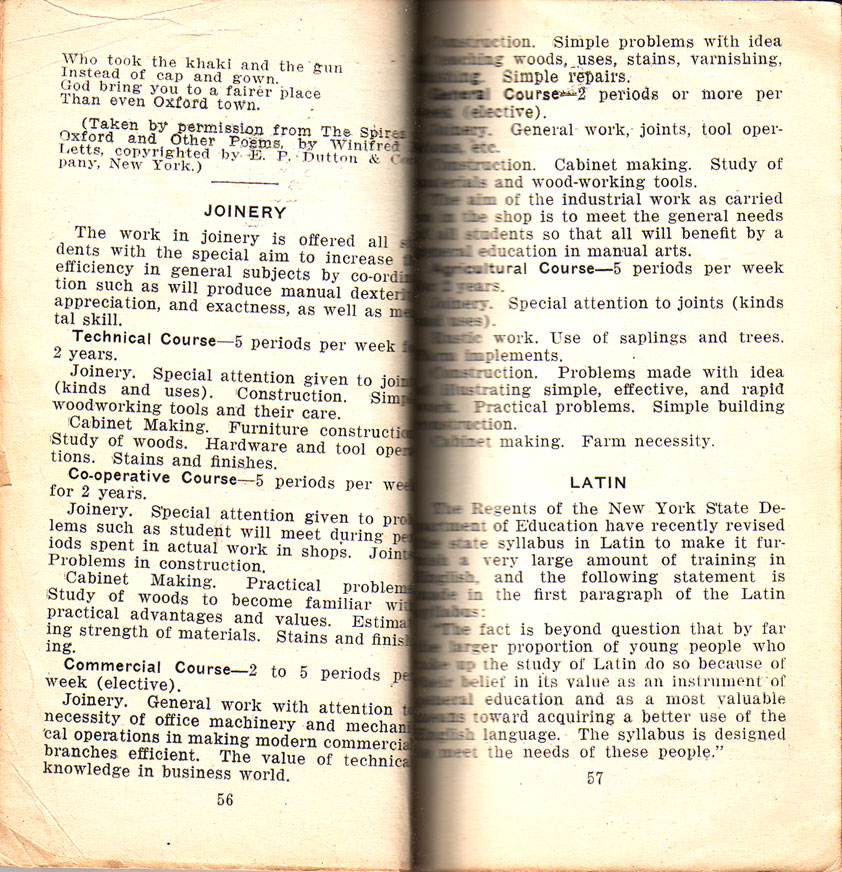

And the curriculum! Unlike today’s Newtown High School, there’s Biology, Chemistry,…

… and Freehand Drawing. Given his work for the school literary magazine and his later success as “Crockett Johnson,” I imagine that young Dave Leisk took these classes.

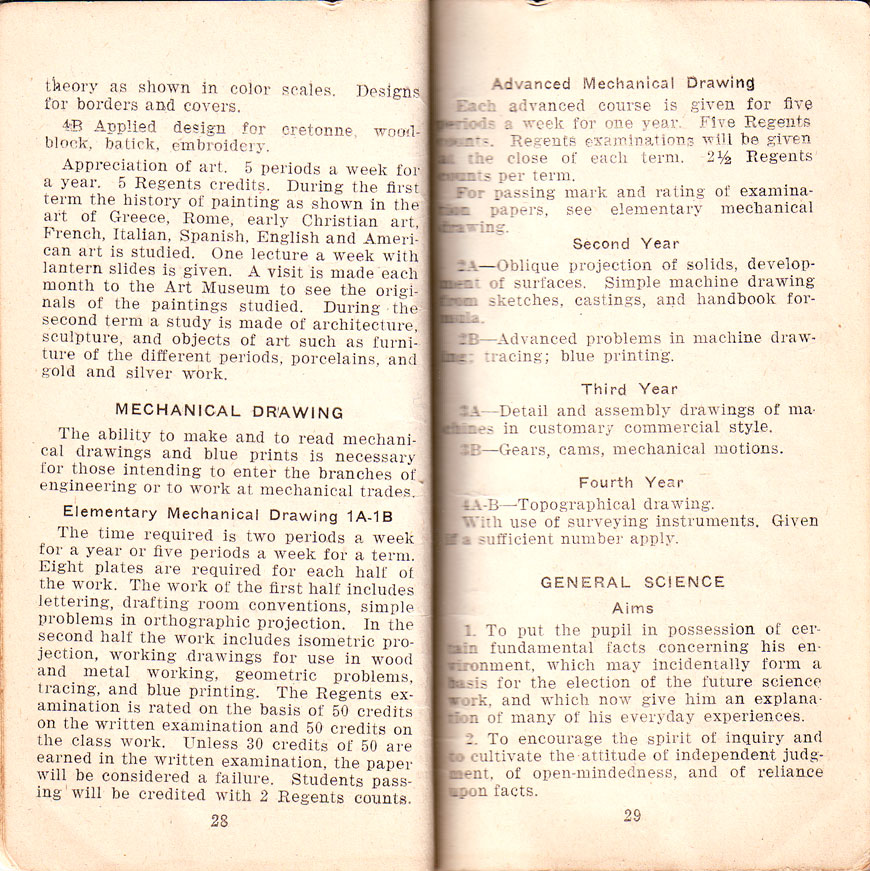

More curricula: Mechanical Drawing, General Science,…

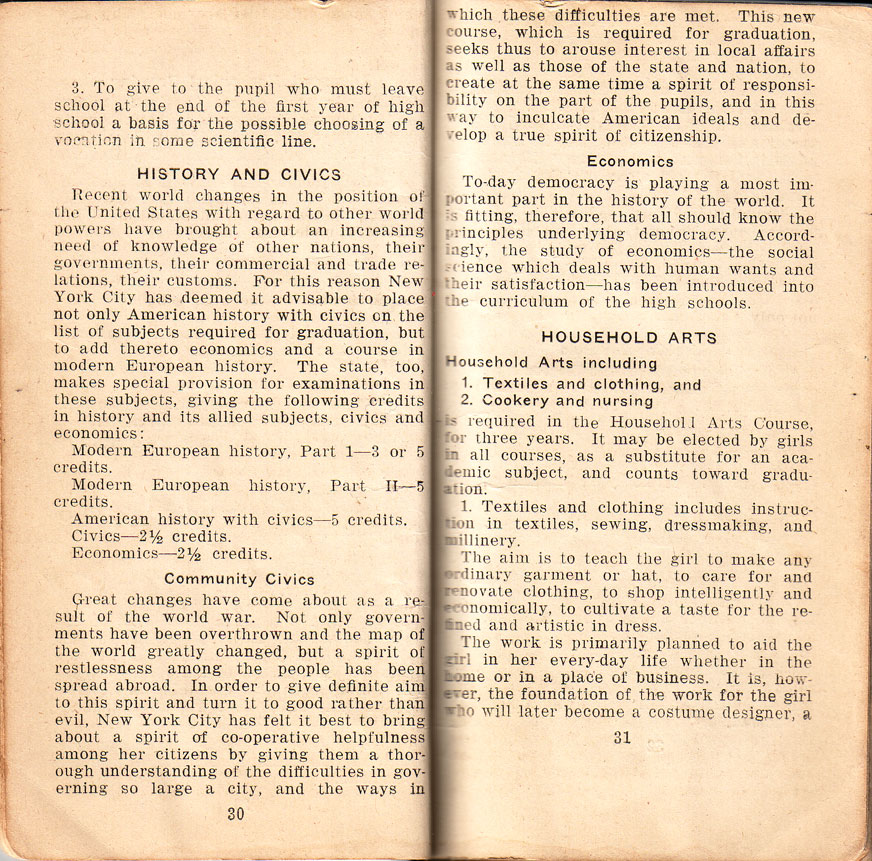

… History and Civics, and Household Arts –Â which, you’ll note, “may be elected by girls in all courses, as a substitute for an academic subject, and counts toward graduation.” Â Just by girls, mind you. Â Boys have to take the “academic subjects.”

The “Cookery and nursing” course in Household Arts “aims to make the girl a good homemaker and enthusiastic expert in home administration, who will put new life and interest into the old story of ‘Cooking’ and ‘Housekeeping.” Ah, socialization – and, very likely, one reason that you’ve heard of Crockett Johnson, but not of his sister Else.

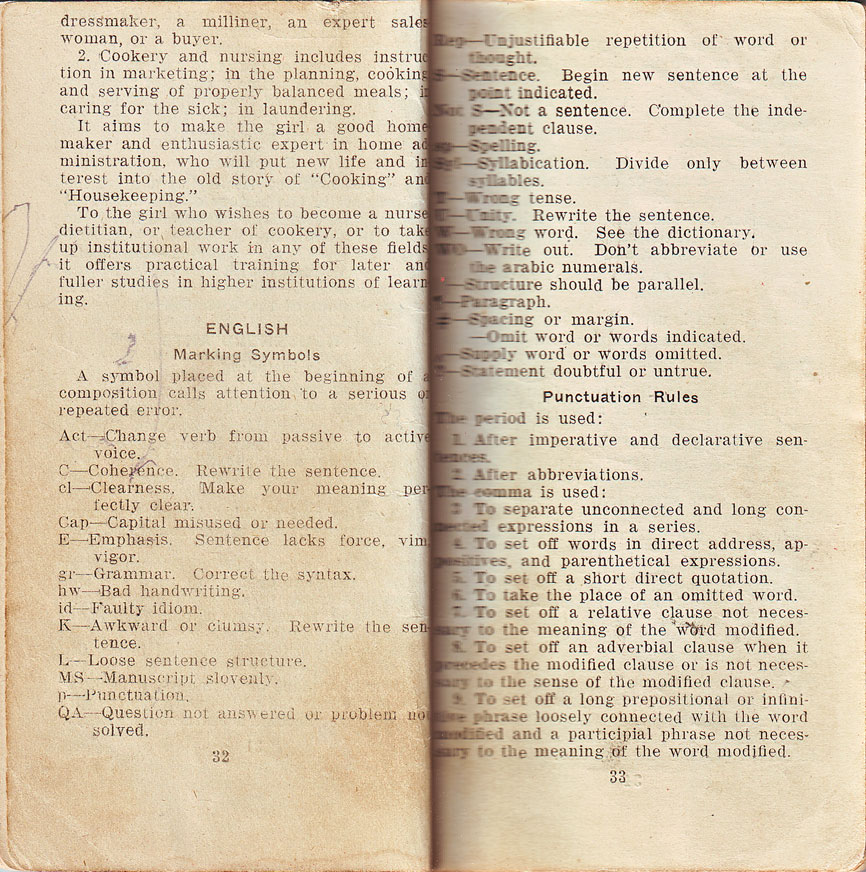

On to English! As a professor of English, I’m most intrigued by the one I don’t understand: “U – Unity. Rewrite the sentence.” Although I’ve certainly encountered sentences that lack unity, this directive doesn’t convey why the sentence lacks unity. And I get a big kick out of “MS – Manuscript Slovenly.” Sure, we’ve all seen these, but I expect that few of us have used this particular locution to describe their substandard condition.

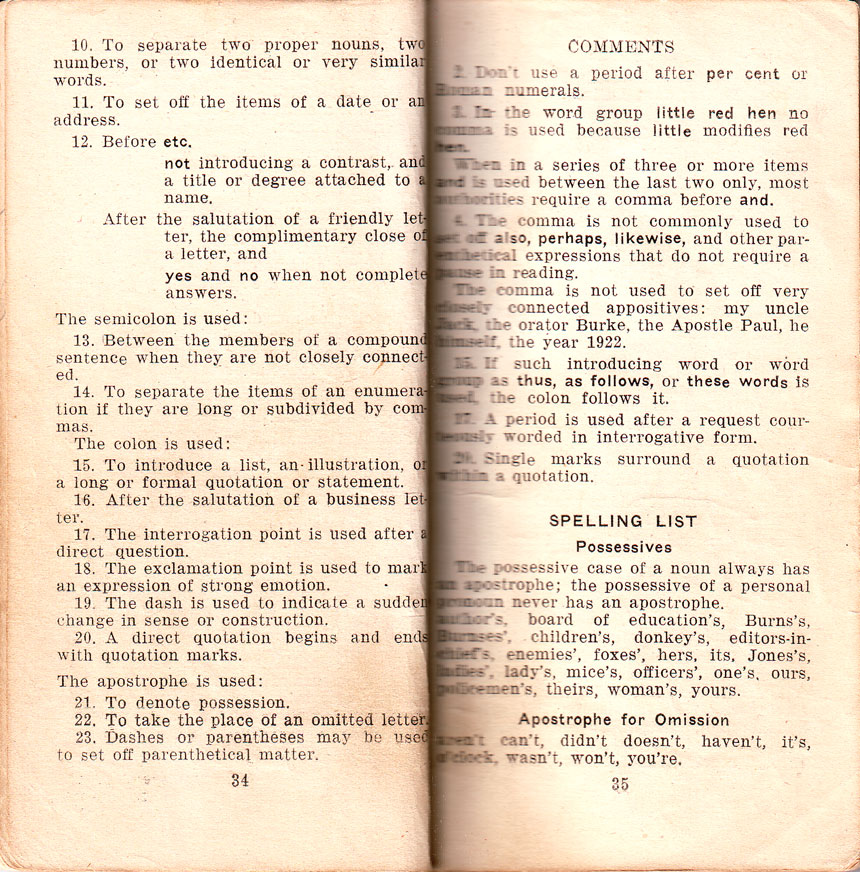

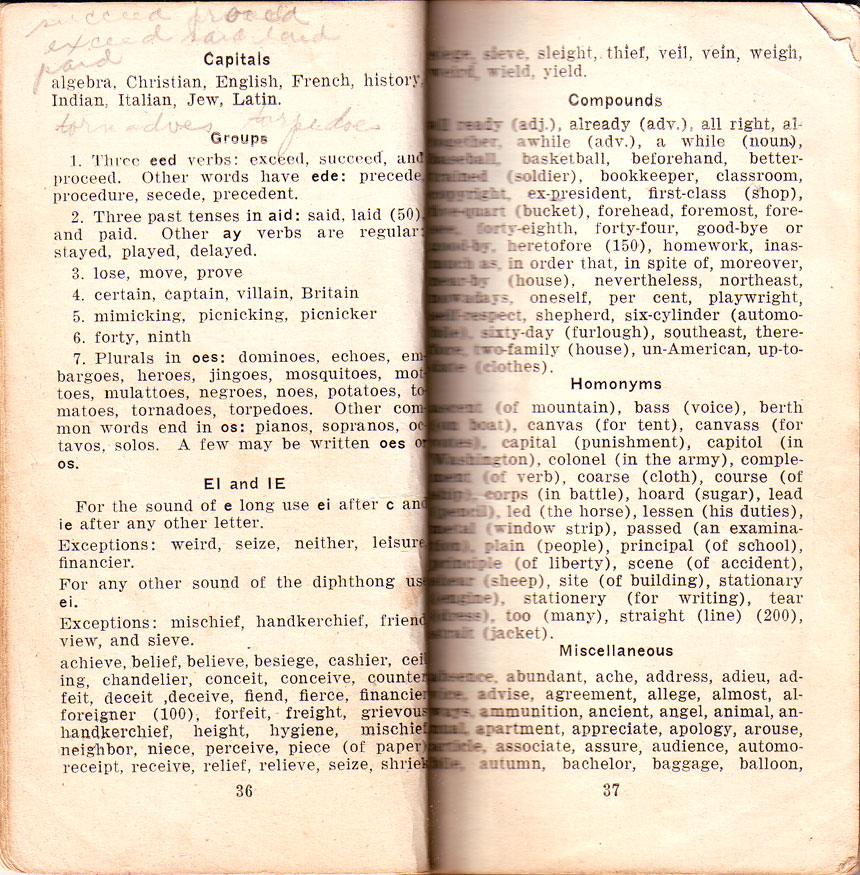

Following these rules, a “Spelling List” extends for eight pages, with groups of words in sub-lists identified by different types of common errors … all of which are (sadly) common at the college level today. You can see the first two types above (“Possessives,” “Apostrophe for Omission”). Below, “Capitals,” “Groups,” “EI and IE,” “Compounds,” and “Homonyms”:

That Newtown High School was racially integrated makes particularly interesting the inclusion (in the 7th item of “Groups”) of “mulattoes, negroes.” Â Such words would have been viewed as “neutral” to the faculty who assembled the handbook – “mulatto” indicated someone of “mixed race,” and “negro” described someone “black” or “African-American.” Â I’m placing all of these racial terms in inverted commas because they’re social constructs: When it comes to human beings, “race” is purely imaginary (we’re all part of the human race). Â However, as this handbook suggests, people deploy such imaginary categories in very real ways. Â That two of fourteen examples are racial classifications suggest that these racial designations were in common use.

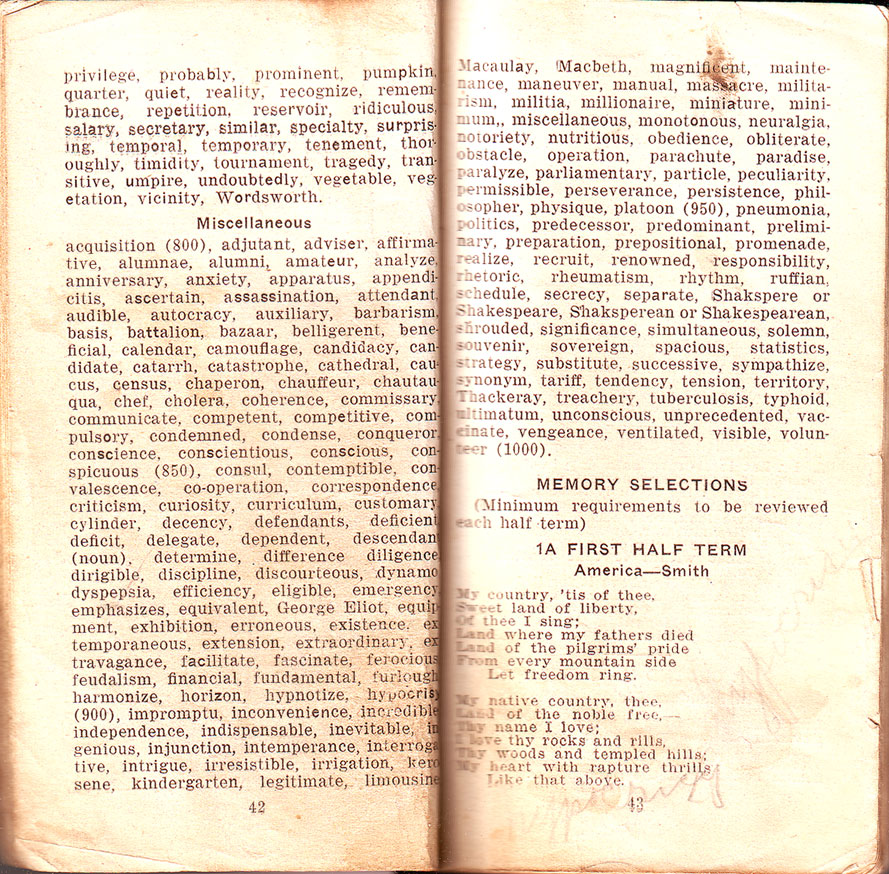

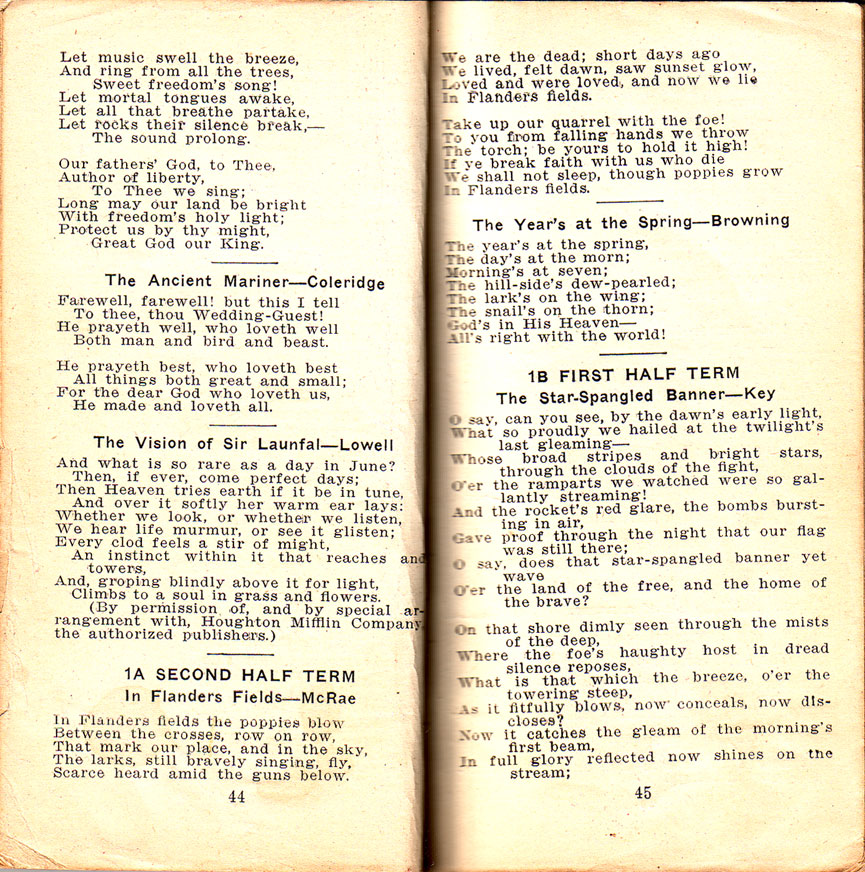

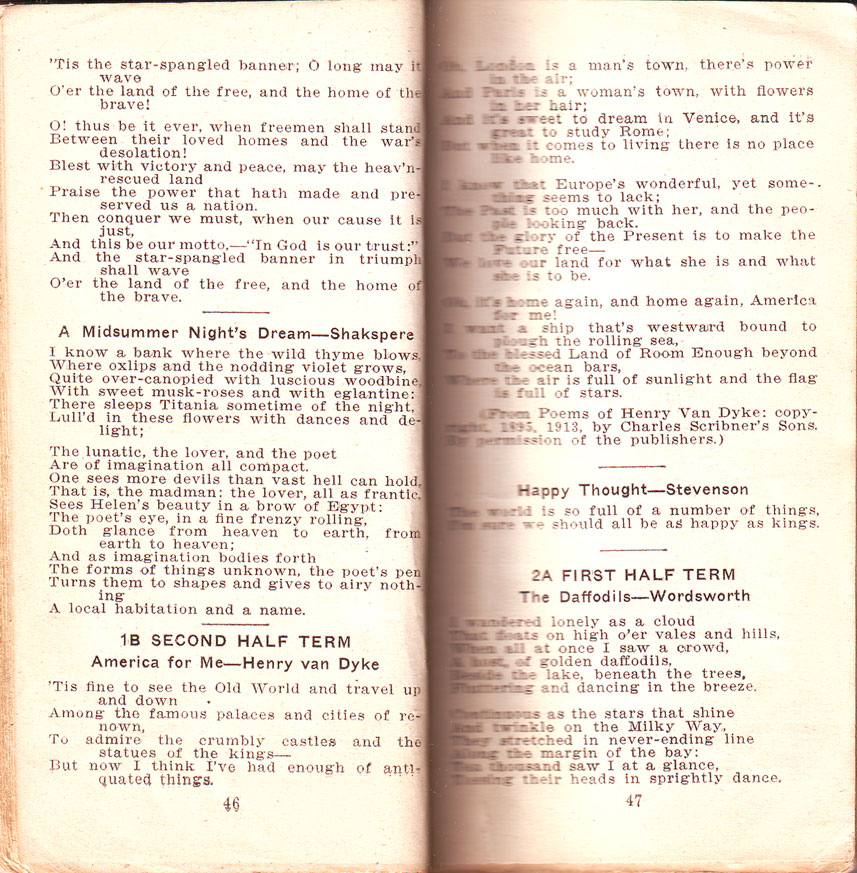

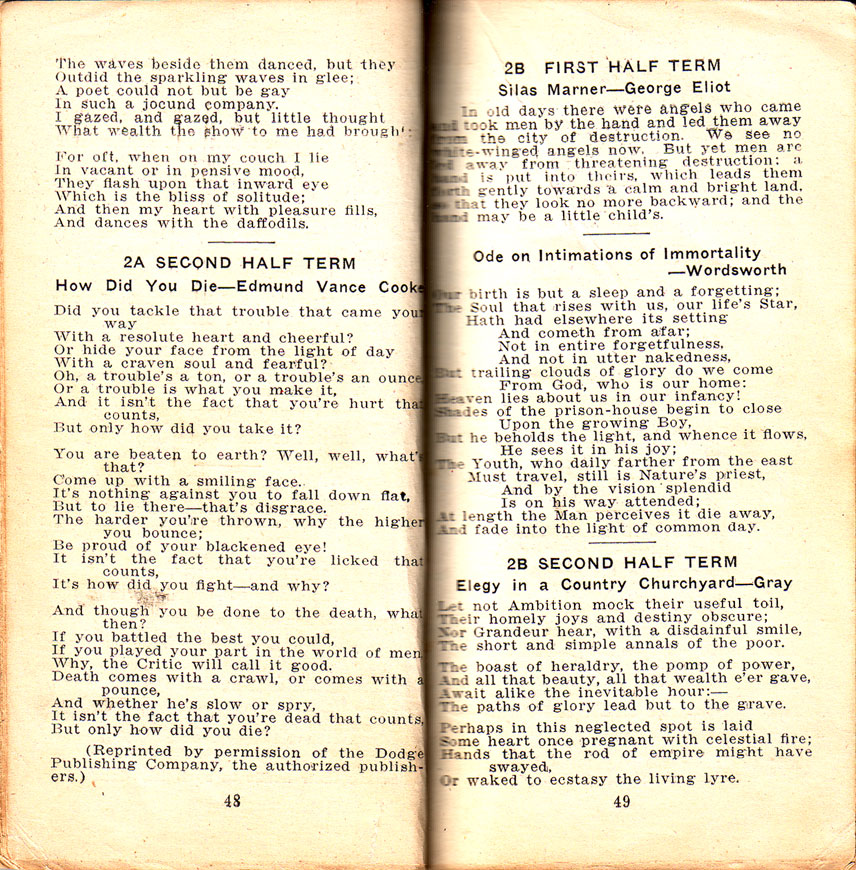

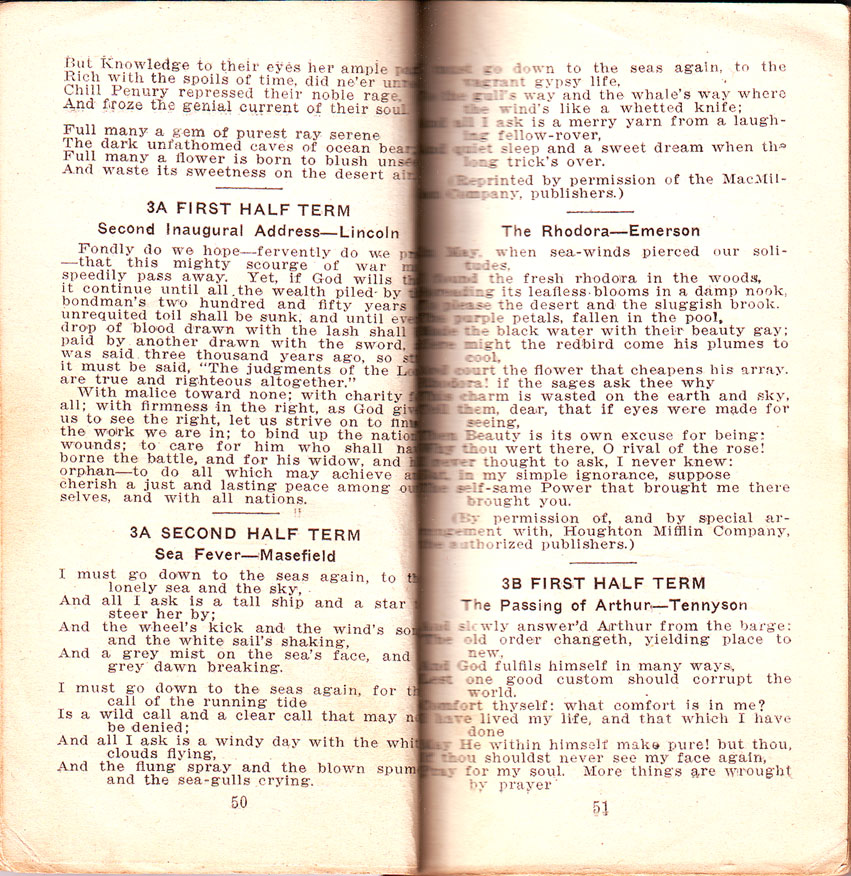

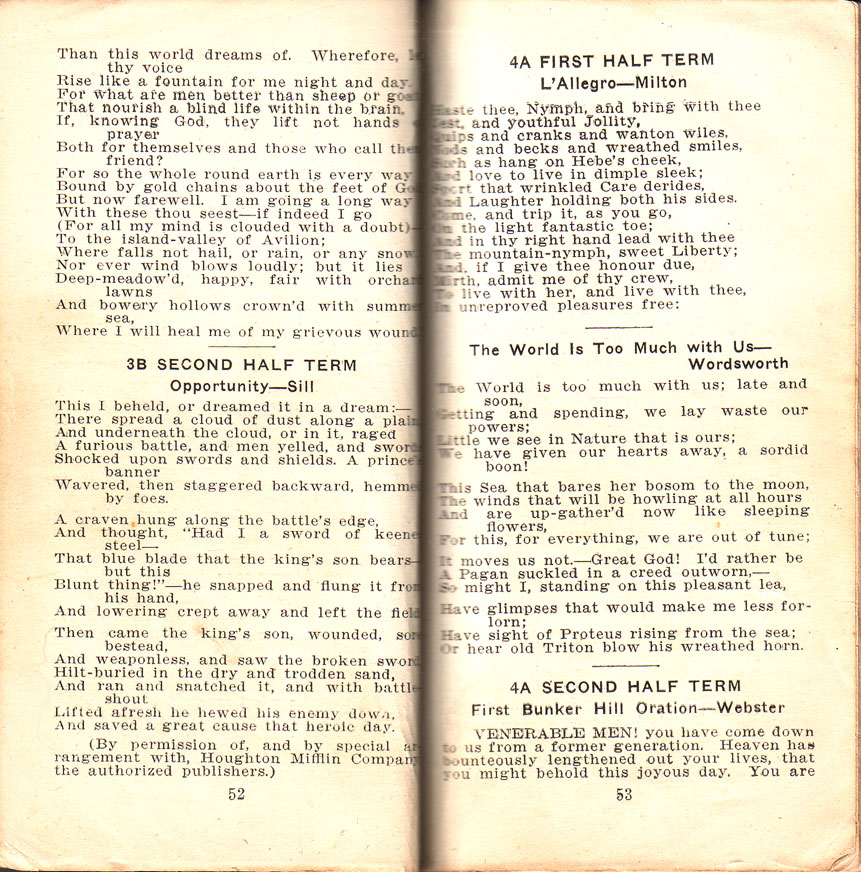

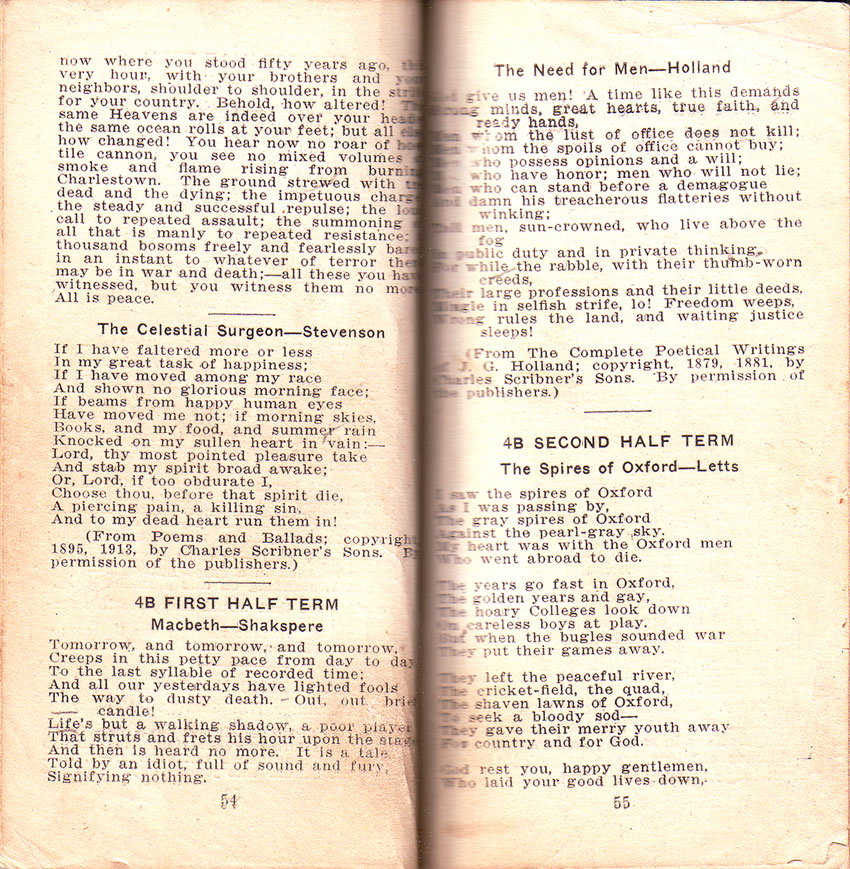

In addition to serving as a grammar textbook, the Newtown High School Handbook was a literary anthology. Â Its “Memory Selections” offer a sense of what were considered “canonical” literary works for high school students in 1921:

Here’s a breakdown of canonical works by author:

- 3 from William Wordsworth.

- 2 from Robert Louis Stevenson, William Shakespeare.

- 1 from Samuel Francis Smith, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, James Russell Lowell, John McCrae, Robert Browning, Francis Scott Key, Henry Van Dyke, Edmund Vance Cooke, George Eliot, Thomas Gray, Abraham Lincoln, John Masefield, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Edward Rowland Sill, John Milton, Daniel Webster, Josiah Gilbert Holland, Winifred Mary Letts.

By gender:

- Works by men: 24.

- Works by women: 2

By nationality:

- Works by English authors: 15

- Works by American authors: 10

- Work by Canadian author: 1

By date:

- The most recent works are Letts’ “The Spires of Oxford” (1916) and McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields” (1915), both patriotic poems in support of the Allied effort in World War I.

- The earliest works are the excerpts from Shakespeare’s Macbeth (c. 1603-1606) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (c. 1594-1596)

An on it goes, up to page 128 – the final six pages are advertisements.  Had we but world enough and time (a poem not included here), I’d take you through the second half.  But we do not.  Indeed, I would be surprised if anyone is reading these final few sentences.  This is, I know, a rather long post.

Cecil

Linda Kaplan Councill

Alexandra Vasiliadis