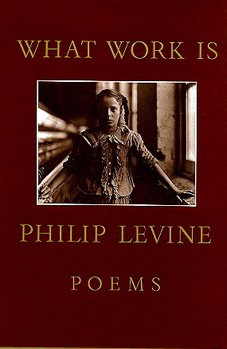

Yesterday, songs.  Today, a poem.  There are many poets to whom we might turn (Whitman and Sandburg rush to mind) for Labor Day, but I’ve opted for the title poem from What Work Is (1991) by America’s new Poet Laureate Philip Levine (b. 1928).  When you hear him read, he often shares a story about the poem – indeed, these succinct autobiographical narratives would make for a great collection of prose (were he so inclined).  So, here’s a recording of him reading “What Work Is,” including one of those introductions (he starts speaking at around 12 seconds in):

Yesterday, songs.  Today, a poem.  There are many poets to whom we might turn (Whitman and Sandburg rush to mind) for Labor Day, but I’ve opted for the title poem from What Work Is (1991) by America’s new Poet Laureate Philip Levine (b. 1928).  When you hear him read, he often shares a story about the poem – indeed, these succinct autobiographical narratives would make for a great collection of prose (were he so inclined).  So, here’s a recording of him reading “What Work Is,” including one of those introductions (he starts speaking at around 12 seconds in):

He’s a wonderful reader of his own work. Â And here is the poem itself:

We stand in the rain in a long line

waiting at Ford Highland Park. For work.

You know what work is–if you’re

old enough to read this you know what

work is, although you may not do it.

Forget you. This is about waiting,

shifting from one foot to another.

Feeling the light rain falling like mist

into your hair, blurring your vision

until you think you see your own brother

ahead of you, maybe ten places.

You rub your glasses with your fingers,

and of course it’s someone else’s brother,

narrower across the shoulders than

yours but with the same sad slouch, the grin

that does not hide the stubbornness,

the sad refusal to give in to

rain, to the hours of wasted waiting,

to the knowledge that somewhere ahead

a man is waiting who will say, “No,

we’re not hiring today,” for any

reason he wants. You love your brother,

now suddenly you can hardly stand

the love flooding you for your brother,

who’s not beside you or behind or

ahead because he’s home trying to

sleep off a miserable night shift

at Cadillac so he can get up

before noon to study his German.

Works eight hours a night so he can sing

Wagner, the opera you hate most,

the worst music ever invented.

How long has it been since you told him

you loved him, held his wide shoulders,

opened your eyes wide and said those words,

and maybe kissed his cheek? You’ve never

done something so simple, so obvious,

not because you’re too young or too dumb,

not because you’re jealous or even mean

or incapable of crying in

the presence of another man, no,

just because you don’t know what work is.

Levine’s third line says “You know what work is,” and his final line says “you don’t know what work is.” Â Between those two statements, the poem proves that we don’t know what work is… by giving us a deeper knowledge of what work is. Â It educates us in order to expose the depths of our ignorance.

Offering a nuanced examination of “work,” labor of the type celebrated by Labor Day oscillates between background and foreground. Â The speaker is at “Ford Highland Park,” his brother “Works eight hours a night,” and “somewhere ahead” a man can deny them work “for any / reason he wants.” Â This sort of physical labor creates the setting for and underwrites the intensity of feeling behind the emotional labor the poem’s speaker works through – the necessary, vulnerable act of expressing love for another person. Â “How long has it been since you told him / you loved him,” the speaker asks, before admitting to himself “You’ve never / done something so simple, so obvious” because he doesn’t know “what work is.” Â The work of loving a brother, he suggests, is not just the harder work, but the far more important work, and a work that we do not, cannot, fully understand.

I like, too, how the tonal shifts create not distance from the brother, but intimacy – both by conveying the speaker’s feelings, and by offering specific details about the brother’s life. Â In the first shift, the speaker changes the reference of the pronoun “you,” moving from his audience to himself: “Forget you. This is about waiting,” he says, returning to a different “you” a few lines later. Â The deliberate affront of “Forget you” evokes an emotion from the reader, setting the stage for another tonal shift later on. Â After describing his brother in sympathetic terms, our speaker reports that he “Works eight hours a night so he can sing / Wagner, the opera you hate most, / the worst music ever invented.” The frank rejection of his brother’s taste in music suggests both that perhaps the two have argued about it, and that the speaker dislikes Wagner with a comparable passion to his brother’s love for Wagner. This abrupt criticism’s context – expressing admiration and love for the brother – drains the remark of any animosity, suggesting instead that the speaker’s love is that much deeper because he dislikes his brother’s favorite composer, and admires the brother for singing it anyway.

Though the referent of the pronoun “you” shifts from audience to speaker, it also does not shift. Â With each invocation of that pronoun “you,” the speaker interpellates the reader into his second-person subjecthood. Â When he says, “suddenly you can hardly stand / the love flooding you for your brother,” he asks us to experience that intense love for our brother (or sister or mother or cousin or best friend). Â When he says “you don’t know what work is,” he is not just accusing himself; he is accusing us, too. Â And he makes a convincing case. Â The work for which we are paid robs us of the time to be with, and sometimes to be loving towards, the people who are most important to us. Â How much of our daily life do we spend away from the people we love the most? Â When will we next see that sibling, parent, old friend, niece, uncle again? Â (Indeed, will we see them again?)

It’s a powerful poem.  And Levine is one of our great poets.  I recommend What Work Is, The Simple Truth (1994), and – if you’d like a larger collection of earlier work – New Selected Poems (1991).  I’m embarrassed to admit that I’ve not read his most recent collection, News of the World (2009).  But I’ve just ordered myself a copy.