Those of us who read, create, study, or teach children’s literature sometimes face skepticism from other alleged adults. Why would adults take children’s books seriously? Shouldn’t adults be reading adult books?

There are many responses to these questions:

- Children’s books are the most important books we read because they’re potentially the most influential books we read. Children’s books reach a young audience still very much in the process of becoming. They stand to make a deeper impression because their readers are much more impressionable.

- Adults who dismiss children’s literature neglect their responsibilities as parents, educators, and citizens. What future parents, teachers, doctors, construction workers, soldiers, leaders, and neighbors read is of the utmost importance, if for no other reason than some of us will continue to live in the world they inherit. If books leave such a powerful impression on young minds, then giving them good books is vital.

- Almost no children’s literature is written, illustrated, edited, marketed, sold, or taught by children. Adults – and adults’ idea of “children” – create children’s books. It’s profoundly hypocritical for an adult to suggest children’s literature as unworthy of adult attention. Indeed, adults who make such claims are either hypocrites, fools, or both.

- Children are as heterogeneous a group as adults are. There is no universal child, just as there is no universal adult. Defining the readership of any work of “children’s literature” is a tricky, sticky, complex task. Paradoxically and as the term itself indicates, “children’s literature” is defined by its audience – it’s for children. It thus a literature for an audience whose tastes, reading ability, socio-economic status, hobbies, health, culture, interests, gender, home life, and race varies widely. Children’s literature is literature for an unknowable, unquantifiable group. The very term “children’s literature” is a problem. Only someone who has never thought about children or what they read could argue that children’s literature does not merit serious consideration.

- Children’s literature has aesthetic value. Good children’s books are literature. Good picture books are portable art galleries. If we don’t take children’s literature seriously, then we diminish an entire art form and those who read it. We also prevent ourselves from being able to distinguish quality works from inferior ones – thus neglecting our responsibilities outlined in no. 2, above. This is not to suggest that we can or should all agree on what is a great children’s book. We can’t and we shouldn’t. What we can and should do is care about what makes children’s books bad or good, average or classic, banal or beautiful.

But my focus in this post is less on those preceding five points (or the many other points that could be added) and more on a sixth point: that children’s books have much to give those of us who are no longer children. There are levels of meaning we may have missed when we read the book as a child. There are experiences adults have that grant us interpretations unavailable to less experienced readers – just as children may arrive at interpretations unavailable to adults who have forgotten their own childhoods. In children’s books, there is art, wisdom, beauty, melancholy, hope, and insight for readers of all ages.

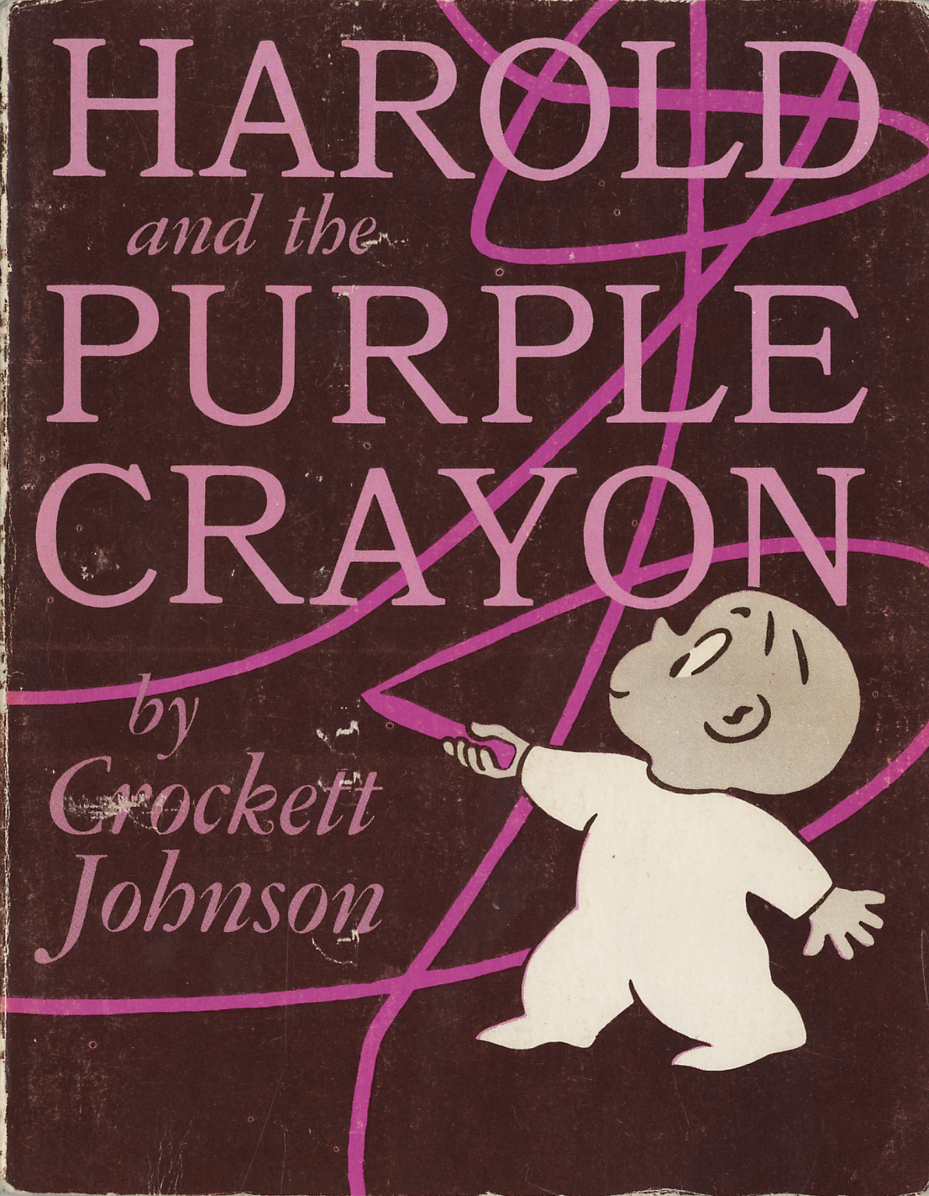

What inspires me to make this sixth claim is that I have no memory of reading Harold and the Purple Crayon as a child. As an adult, I created a website devoted to the book’s creator, Crockett Johnson, and wrote a biography of Johnson and his wife, fellow-children’s book writer Ruth Krauss. But the book that inspired both website and biography is completely absent from my memories of early childhood.

What inspires me to make this sixth claim is that I have no memory of reading Harold and the Purple Crayon as a child. As an adult, I created a website devoted to the book’s creator, Crockett Johnson, and wrote a biography of Johnson and his wife, fellow-children’s book writer Ruth Krauss. But the book that inspired both website and biography is completely absent from my memories of early childhood.

The book does appear in memories of those memories. In eighth grade, when I had long since “graduated” into reading chapter books, my mother got a job teaching at a private school, thus enabling my sister and I to attend the school for free. Once a week (or was it once a month?), there was a faculty meeting after the end of the school day. During that meeting, my sister and I were left alone in the school library to do our homework. She did her homework. I did not. Instead, I wandered over to the picture books and began reading them. There, I rediscovered Harold and the Purple Crayon, a book I then remembered fondly from my pre-school days. I also realized that there were other books about Harold – Harold’s Trip to the Sky, Harold’s ABC. Had I read these other Harold stories when I was younger? I wasn’t sure. But I knew they were just as enchanting as the first Harold book.

So, at the age of 14 – an age when you might expect a person to be reading Young Adult novels – I began to collect paperbacks of Crockett Johnson’s Harold books.

I don’t know what needs were fulfilled by those particular words and pictures. Perhaps it was the books’ presentation of the imagination as a source of power and possibility. Maybe Harold’s iconic, clear-line style better enabled me to identify with him as he, and his crayon, navigated an uncertain, emerging landscape.

For that matter, I don’t know why, as a freshman in college, I adopted as my bedtime reading A. A. Milne’s The World of Pooh and The World of Christopher Robin. (The former contains both Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at Pooh Corner; the latter collects all the verse from When We Were Very Young and Now We are Six.)

My point is that books “for children” can speak to people of all ages and backgrounds – if we are ready to listen. It’s hard to predict when or why we will be ready to listen. It is indeed dangerous to assume that recommended age-ranges on the backs of books will tell us anything about who may read those books. When I read and re-read the Harold stories at age 14, the books did not then have age ranges on them, though I note that a more recent copy of Harold’s Fairy Tale claims it’s for “Ages 3 to 8.” As Philip Pullman has said of his own work,

I did not intend the book for this age, and not that; for one class of reader, and not others. I wrote it for anyone who wants to read it, and I want as many readers as I can get, and I want to meet them honestly…. For a book to claim “This was written for children of 11+”, when it simply wasn’t, is to tell an untruth.

Exactly.

Books “for children” or “for teenagers” are books for all who are ready to listen to them. They are for all who recognize that art cannot be confined within such narrow labels.

Update, 21 Sept 2015: A revised, expanded, and much better version of the above now appears in the Iowa Review‘s Fall 2015 issue. Check it out!

Celia keenan

Steven Withrow

Perry Nodelman

Philip Nel

Robin Bernstein

Philip Nel

Roswitha

Virginia Lowe

jill Carter-Hansen

Perry Nodelman

Liz Parrott

Philip Nel

Aaron Kashtan

Gloria Hardman

Rosanne Parry

Pingback: Weekend Reading: Children's Literature Link Roundup | Super Simple Learning Blog

Pingback: Links for Online Assigned Materials | Childhood's Places

Pingback: Picturebooks and Age-Appropriateness – SLAP HAPPY LARRY