We’ve had a lot of luck with records. Some of the songs that have made our names a household word – like “slop-bucket” – are the little series of animal songs that we’ve been writing.

–Â Michael Flanders, introduction to “The Gnu,” At the Drop of a Hat (1960)

As Michael Flanders says, the animal songs made him and his partner Donald Swann famous. The duo’s best-known such number may be “The Hippopotamus,” with its cheerful, waltzing chorus of

As Michael Flanders says, the animal songs made him and his partner Donald Swann famous. The duo’s best-known such number may be “The Hippopotamus,” with its cheerful, waltzing chorus of

Mud, mud, glorious mud!

Nothing quite like it for cooling the blood.

So follow me, follow

Down to the hollow,

And there let us wallow

In glorious mud!

Indeed, I suspect that even a few Americans know this one. I say that because, if you are English, you’re very likely to at least have heard of Flanders and Swann. If you are American, well, that’s much less likely. (In terms of Flanders-and-Swann awareness, Canadians seem somewhere in between – more than Americans, but less than Britons.) So, to acquaint or re-acquaint yourself with Flanders and Swann, let’s listen to “The Hippopotamus.”

There’s even a children’s-book version of this, The Hippopotamus Song: A Muddy Love Story (1991), illustrated by Nadine Bernard Westcott. (I haven’t seen the book, and so can’t vouch for how well or poorly the song has been adapted.)

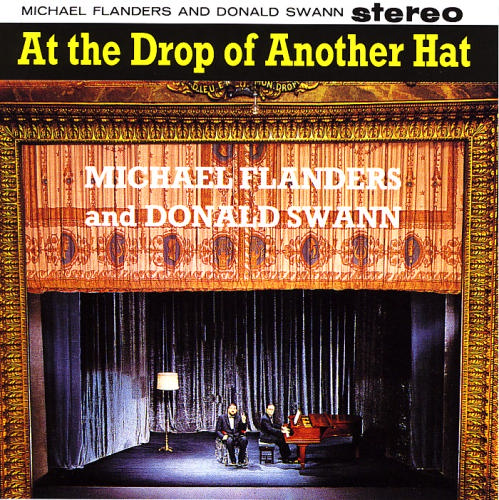

If you’re unfamiliar with this duo, you might think of Flanders (1922-1975) and Swann (1923-1994) as something of a British Tom Lehrer (b. 1928), but without the cynicism. As Flanders himself observes in At the Drop of Another Hat (1964), “The purpose of satire, it has been rightly said, is to strip off the veneer of comforting illusion and cosy half-truth – and our job, as I see it, is to put it back again.” They are satirists, but (usually) lack the aggression of Lehrer, favoring instead satire’s sense of play and a kind of wry, bemused judgment – or, in the case of songs like “The Hippopotamus,” more whimsy than judgment.

If you’re unfamiliar with this duo, you might think of Flanders (1922-1975) and Swann (1923-1994) as something of a British Tom Lehrer (b. 1928), but without the cynicism. As Flanders himself observes in At the Drop of Another Hat (1964), “The purpose of satire, it has been rightly said, is to strip off the veneer of comforting illusion and cosy half-truth – and our job, as I see it, is to put it back again.” They are satirists, but (usually) lack the aggression of Lehrer, favoring instead satire’s sense of play and a kind of wry, bemused judgment – or, in the case of songs like “The Hippopotamus,” more whimsy than judgment.

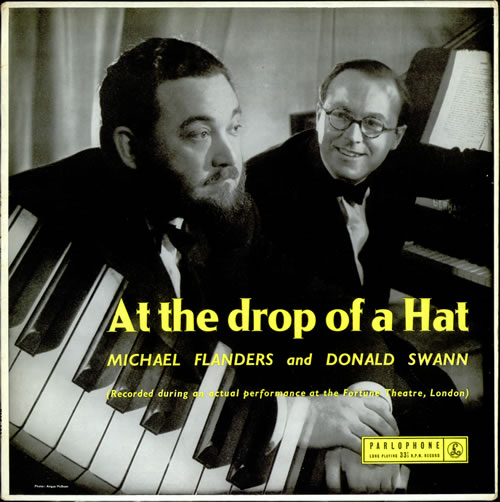

Though Lehrer famously set his “The Elements” to Gilbert and Sullivan’s “Major-General’s Song,” the librettist and composer of The Pirates of Penzance had a much stronger influence on Flanders and Swann. Flanders was the Gilbert, writing nearly all of the lyrics, and Swann the Sullivan, writing all of the music (and the occasional lyric). With wit, wordplay, and complex rhyme schemes, the duo wrote over a hundred songs, and between 1956 and 1967 gave hundreds of performances in the UK, Canada, and the US –Â plus, in 1964, a few in Australia and New Zealand. George Martin (yes, the Beatles’ producer) produced their best-known albums. David Hyde-Pierce and John Lithgow are probably the duo’s best-known contemporary fans.

Never heard of Flanders and Swann? Or care to be reacquainted? Well, here’s my (admittedly subjective) list of essential songs, complete with audio, commentary, and (when available) video. The first was “The Hippopotamus Song” (above); so, moving to the second….

2) “A Transport of Delight”

A paean to the “monarch of the road,” that “Scarlet-painted London Transport, Diesel-engined, Ninety-seven horsepower Omnibus!” Swann takes on the role of driver, Flanders the conductor, and they sing heartily, with a mix of affection and mockery.

A paean to the “monarch of the road,” that “Scarlet-painted London Transport, Diesel-engined, Ninety-seven horsepower Omnibus!” Swann takes on the role of driver, Flanders the conductor, and they sing heartily, with a mix of affection and mockery.

A few allusions of note. “Earth has not anything to show more fair” is from Wordsworth’s “Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802.” “Army lorry” puns on the Scots song “Annie Laurie,” which includes the line “And for bonnie Annie Laurie, / I’d lay me down and dee” (“dee” being a Scots pronunciation of “die”).

3) “The Gas-Man Cometh”

The GALMI method has its flaws, as this song points out. (No, the song doesn’t use the expression “GALMI,” but that’s an acronym for “Get A Little Man In.” I’ve heard it on British sitcoms.)

4) “First and Second Law”

Showing their range, Swann and Flanders explain thermodynamics via a jazzy scat number. This is still the reason I know anything about thermodynamics. You see, Flanders and Swann are the music of my childhood. Though I grew up north of Boston Massachusetts, my parents lived in London during the latter half of the 1960s. They even saw Flanders and Swann perform there. In the U.S., borrowing the records from friends, my dad taped, on a reel-to-reel (the bulkier predecessor of the cassette recorder), At the Drop of a Hat and At the Drop of Another Hat – though I later learned that he only taped the pieces that he liked. Fortunately, that was the majority of each record.

5) “The Gnu”

In the introduction (which I’ve omitted), Michael Flanders talks about the song’s inspiration, which involves being unable to park (or get out of his car) on the street where he lives:

The road itself is a bit of a snag. That road has got the steepest camber on it – you know, the old slope – of any road in London. It’s about one in three. If you try to park your car by the pavement, as people do from time to time, the car’s tilted, like that. Well now, that means you can only get this near-side door open a little bit, then the pavement stops it. If you want to use this door you can make a jump for it. Bad enough all up and down the road, but just outside where I happen to live, 1a (of course it would be), it’s just like the great North face of Everest. The thing’s right over on its side. You can’t get this door open at all, you’ve got to keep it full of petrol or it shows empty. I can’t use this door, I’ve got to get into this thing [Flanders’ wheelchair], you see, on the pavement.

He asks his local council about it, and they send a man round to take a chunk out of the road so that it’s level in front of Flanders’ house, thus allowing him to navigate from his car to his wheelchair and vice versa. However, ever time he arrives at his space, someone else is parked there –Â always the same car. “The number of this car,” he says, “I’ll never forget this number as long as I live. I’ve sat gazing at it for hours on end sometimes, thinking of nothing else. The number is 346-GNU.”

In case you are doubtful, a gnu is a real animal. The Oxford English Dictionary describes it as a “South African quadruped (Catoblepas gnu), belonging to the antelope family, but resembling an ox or buffalo in shape; also known by its Dutch name wildebeest.”

6) “Misalliance”

In which two plants become star-crossed lovers, a silly premise with a plaintive melody that makes it curiously affecting.

7) “Madeira M’Dear”

A bit more risqué than the other songs here, “Madeira M’Dear” contains excellent zeugma, when one word gets used to refer to more than one word in the same sentence.  These particular lyrics often use the first word (the multi-referential one) in more than one sense. So, for example, “She lowered her standards by raising her glass, / Her courage, her eyes – and his hopes.”

Here are Flanders and Swann performing the song for American television in 1967. Flanders glosses “flat” as “apartment” for American viewers and – presumably to appease censors – changes “prowess” to “finesse.” Incidentally, if he looks a little breathless, that may be because he has only one working lung. The polio that put him in the wheelchair also took away one of his lungs.

UPDATE, 7 Aug. 2014, 1:30 pm: In retrospect, this song might better be classified among those that have not aged well (described in my caveat below). I direct readers to my conversation with Jonathan Dresner (in the comments) for precisely why.

8) “A Happy Song”

This represents the absurdist side of the duo – also on display in such numbers as “Kokoraki.” If you enjoy Spike Jones or Mel Blanc, then “A Happy Song” is for you. Â It’s one of three “Songs for Our Time” on At the Drop of a Hat, each of which, Flanders explains, is his and Swann’s attempt to write a pop hit. Of this particular one, Flanders tells the audience, “We felt that really, on the whole, in this time of crisis and political conflict, what the world needed most was another simple happy chorus song, something which expressed the feelings of all the ordinary people all over the world, and in which everyone could join.” He then pronounces the song’s nearly unpronounceable refrain, and invites people to “join in, if you wish.”

This represents the absurdist side of the duo – also on display in such numbers as “Kokoraki.” If you enjoy Spike Jones or Mel Blanc, then “A Happy Song” is for you. Â It’s one of three “Songs for Our Time” on At the Drop of a Hat, each of which, Flanders explains, is his and Swann’s attempt to write a pop hit. Of this particular one, Flanders tells the audience, “We felt that really, on the whole, in this time of crisis and political conflict, what the world needed most was another simple happy chorus song, something which expressed the feelings of all the ordinary people all over the world, and in which everyone could join.” He then pronounces the song’s nearly unpronounceable refrain, and invites people to “join in, if you wish.”

9) “The Rhinoceros”

Another reason that Flanders and Swann’s songs are great for children and adults: they expand your vocabulary, as in this song’s refrain, “the bodger on the bonce.” As a noun, “bodger” is “one who bodges; a botcher”; as an adjective, “bodger” is (in Australian slang) a term for “Inferior, worthless.” “Bonce” is a slang term for “head.” So, then, according to the lyric, the rhino has something botched on its head. (All definitions courtesy of the OED.)

10) “The Armadillo”

Who knew that Armadillos had love songs? And with such plaintive melodies, too! Â (The track begins, however, with an elephant joke – the previous song on the record is “The Elephant.”)

11) “Slow Train”

An elegy for closed railway stations, this one is surprisingly poignant. As Flanders says in his introduction,

Unusual song this for us, perhaps, because it’s really quite a serious song, and it was suggested by all those marvelous old local railway stations with their wonderful evocative names, all due to be, you know, axed and done away with one by one, and these are stations that we shall no longer be seeing when we aren’t able to travel anymore on the slow train.

TheGawain provides more detail in this great post on Flanders and Swann. As he tells us, in 1963 Dr. Richard Beeching

wrote a lengthy report on the profitability of British Railways (or lack thereof) and concluded that most of the rail network made no net contribution towards any profits that could potentially be made. He duly recommended removing about half of the route mileage and rather more than half the stations. The Tories implemented the report with unusual haste for any Government; Labour largely opposed it up until the moment when they saw the overall profit/ loss account of the nation and duly decided to continue.

This cross-party enthusiasm for Beeching left very little opportunity for the pro-rail remnants of the population to express any form of opposition except by attempting to prove “undue hardship” at closure inquiries. An examination of the railways which survived on this basis (prime examples include Middlesborough to Whitby, Inverness to Wick & Thurso and Kyle of Lochalsh, Glasgow to Mallaig and Plymouth to Gunnislake) show that in order to demonstrate that closing the local railway would cause undue hardship it was necessary to show that the area was devoid of alternative roads. As a result the minor rural dead loss railways going nowhere which deserved to be axed all survived, while the middling routes serving notable market towns found that the market towns were also served by roads, enabling easy closure of the railways.

The Government then proceeded to spend vast amounts of public money building roads to replace these railways which needed closing down because the Government didn’t have any public money available to spend on keeping them running.

That’s the context for this song. For more, see TheGawain’s piece or this very thorough Wikipedia essay on the song.

12) “The Sloth”

A comic ode to laziness.

Yes, there are many other songs I could have included. Fans of Flanders and Swann will no doubt be asking: What about “Design for Living”? Where’s “A Song of the Weather”? And what about “A Song of Patriotic Prejudice”? Fair questions. I decided to limit myself to a dozen, but I concede that there may be a better twelve songs to introduce people to Flanders and Swann.

A few songs have not aged as well – either because they’re topical, or because casual sexism or imperialism is (happily) no longer culturally acceptable. Remarkably, there are very few such songs. So, on the one hand, “The Reluctant Cannibal” suggests that people everywhere face the same problems, such rebellious children (who, in this case, “won’t eat people”) and parents baffled by their offspring. To their credit, Flanders and Swann also avoid pseudo-primitive dialect, singing in their usual accents. On the other hand, the humor of this piece depends upon the difference between “civilized” society and the more primitive “Tropics” (they don’t provide a specific location where these cannibals reside). The song is not in the realm of, say, the first line of Cole Porter’s “Let’s Do It” (“Chinks do it, / Japs do it. / Up in Lapland, / Even little Laps do it”), but the piece hasn’t endured quite as well as their animal songs.

Interested in learning more? I don’t think there’s an ideal Flanders and Swann “hits” collection. In any case, the live records include amusing spoken-word performances (mostly from Flanders), which would need to be either included or excised –Â in assembling this, I’ve mostly done the latter. You could use iTunes to create your own “hits” collection, and then (depending on your fondness for Flanders’ monologues) either retain or cut the spoken-word parts. In iTunes, you can do that under the “Options” setting of a song, by changing the start time and/or stop time.

Interested in learning more? I don’t think there’s an ideal Flanders and Swann “hits” collection. In any case, the live records include amusing spoken-word performances (mostly from Flanders), which would need to be either included or excised –Â in assembling this, I’ve mostly done the latter. You could use iTunes to create your own “hits” collection, and then (depending on your fondness for Flanders’ monologues) either retain or cut the spoken-word parts. In iTunes, you can do that under the “Options” setting of a song, by changing the start time and/or stop time.

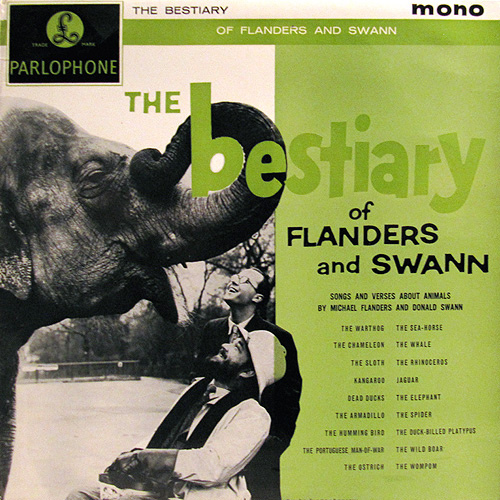

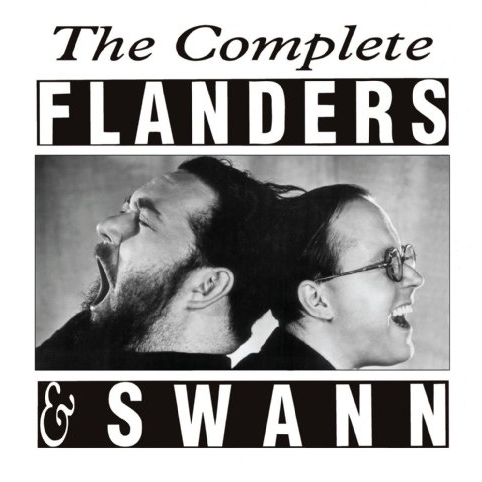

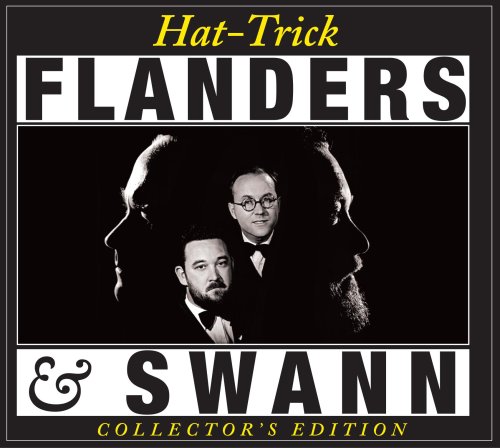

Or, if you seek the full experience, then I recommend The Complete Flanders and Swann, which includes At the Drop of a Hat, At the Drop of Another Hat, The Bestiary of Flanders and Swann plus some bonus tracks, and a great booklet featuring illuminating notes and commentary by Charles Fox. I’ve just discovered there’s another collection with more music I’ve never heard – including many performances not in The Complete Flanders and Swann. Sadly, Hat-Trick: Flanders and Swann Collector’s Edition is out of print.

Or, if you seek the full experience, then I recommend The Complete Flanders and Swann, which includes At the Drop of a Hat, At the Drop of Another Hat, The Bestiary of Flanders and Swann plus some bonus tracks, and a great booklet featuring illuminating notes and commentary by Charles Fox. I’ve just discovered there’s another collection with more music I’ve never heard – including many performances not in The Complete Flanders and Swann. Sadly, Hat-Trick: Flanders and Swann Collector’s Edition is out of print.

Fortunately, Flanders and Swann’s many admirers have gathered lots more information for you to peruse:

- Tim Overton’s Flanders and Swann OnLine

- Donald Swann (official website)

- TheGawain’s Flanders and Swann (blog post, 11 Mar. 2013)

- Flanders and Swann (Wikipeida page)

- Slow Train (Wikipedia page)

- More from Flanders and Swann’s 1967 TV appearance, in which they perform “All Gall” (a topical song about Charles de Gaulle), “My Horoscope,” and “The Armadillo.”

Jonathan Dresner

Philip Nel

Jonathan Dresner

Philip Nel

mark seganish

Philip Nel

Roger Hanington

John S Burton

Stephen Howlett

e. millet

Evan

Philip Nel

KStock

Dean

tim fitzhigham

Maggie Ward

Caroline Vaughan

Alan

William Shafer

Dismal enough

chris taylor

Avital Pilpel

Leon Berger

Anna donnelly

Rob Gerrard

Dr. Mabuse

Tony Young

Alan Wendt

Dr. Mabuse