We tend to imagine the self as an unbroken whole, but it might better be described as plural, a series of selves that, though temporally contiguous (and often overlapping) are not always the “same” self. That’s one of the conclusions suggested by Robert Krulwich in “Who Am I?,” a Radiolab podcast from 2007. It is also a central theme of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), whose protagonist answers the Caterpillar’s question, “Who are you?” like this: “I–I hardly know, Sir, just at present–at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have changed several times since then” (35). Later, she offers to tell the Gryphon “my adventures–beginning from this morning,” adding, “but it’s no use going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then” (81).

We tend to imagine the self as an unbroken whole, but it might better be described as plural, a series of selves that, though temporally contiguous (and often overlapping) are not always the “same” self. That’s one of the conclusions suggested by Robert Krulwich in “Who Am I?,” a Radiolab podcast from 2007. It is also a central theme of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), whose protagonist answers the Caterpillar’s question, “Who are you?” like this: “I–I hardly know, Sir, just at present–at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have changed several times since then” (35). Later, she offers to tell the Gryphon “my adventures–beginning from this morning,” adding, “but it’s no use going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then” (81).

The ever-changing self is one reason that encounters with the past can be surprising. They remind us of earlier versions of ourselves – discarded, forgotten selves. They remind us of parts of our current selves that we no longer recall. They tell us who we were, who we are, and – perhaps – who we have yet to become.

This blog post launches an occasional series of excursions into my past, each one motivated by a particular thing. This first one is Proustian. As he had a cup of tea and a madeleine, Marcel Proust experienced a “shudder,” as his senses transported him to his childhood, when he would wish his aunt Léonie a good morning, and she would give him a madeleine, “dipping it first in her own cup of tea.”

This blog post launches an occasional series of excursions into my past, each one motivated by a particular thing. This first one is Proustian. As he had a cup of tea and a madeleine, Marcel Proust experienced a “shudder,” as his senses transported him to his childhood, when he would wish his aunt Léonie a good morning, and she would give him a madeleine, “dipping it first in her own cup of tea.”

For Proust, it was the taste of madeleines and tea. For me, it was the smell of crayons.

In the process, this past September, of helping my mother move, I had to face the vast archive of my childhood – well over a dozen boxes, some containing items I’d not seen in 30 years. I needed months to sort through it all, but I had only days. She was moving at month’s end, and I couldn’t ship everything from her house to mine. I made snap decisions, some of which I regret. The saddest item to throw out was a cigar box full of crayons, most of them well-worn, some of them broken.

The smell of those crayons transported me to my many childhood hours spent drawing. Then, the boundary between the real world and imagined ones was literally paper-thin. The crayon was the key that opened the door.

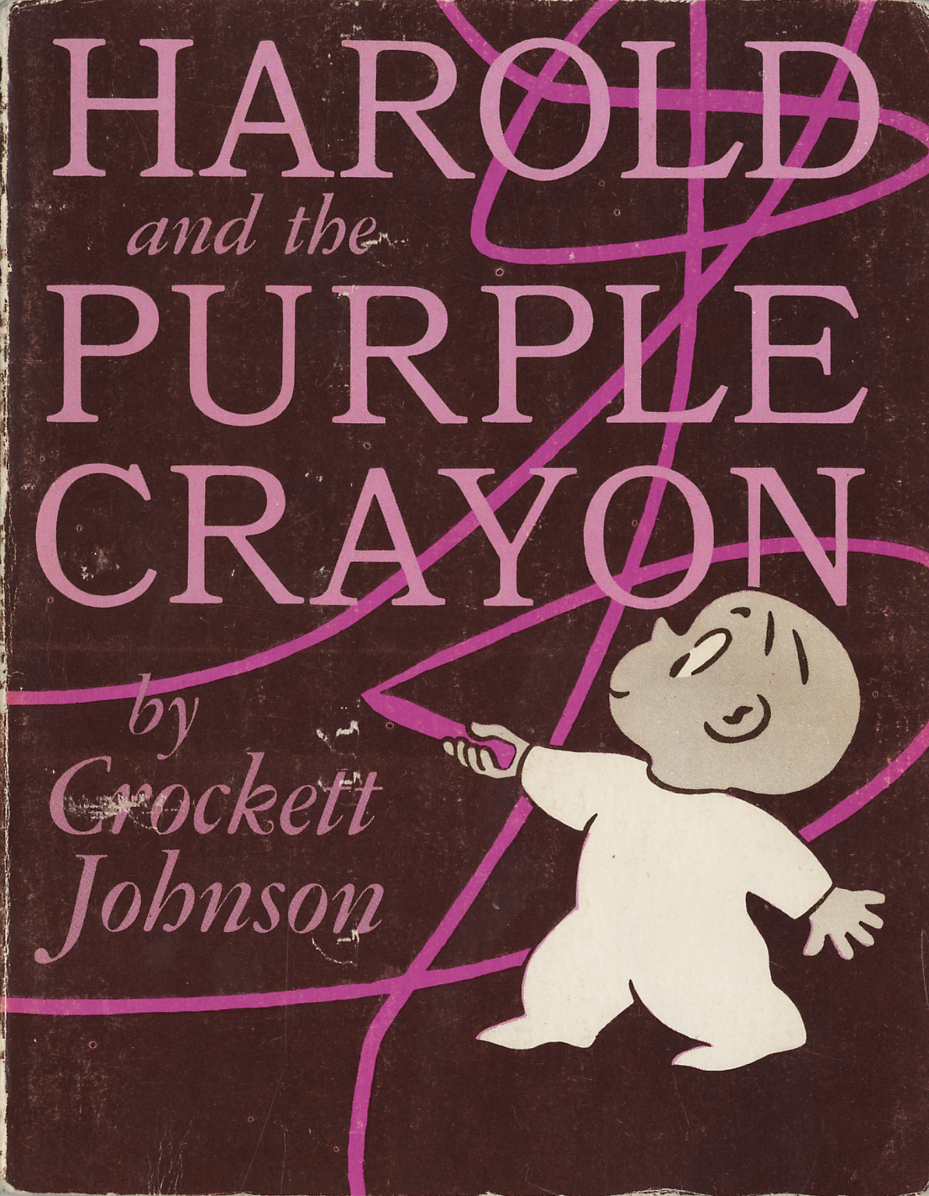

As a child, I knew that my art was only lines on paper (to paraphrase R. Crumb), but it did not feel that way. Drawing was an emotionally immersive experience. While I was moving those crayons across the paper, I was in the drawing, part of it. I realize that this is one reason that Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon resonates on such a deep level. Harold enters his drawing because that’s what childhood art-making feels like.

As a child, I knew that my art was only lines on paper (to paraphrase R. Crumb), but it did not feel that way. Drawing was an emotionally immersive experience. While I was moving those crayons across the paper, I was in the drawing, part of it. I realize that this is one reason that Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon resonates on such a deep level. Harold enters his drawing because that’s what childhood art-making feels like.

Before I threw out the box of crayons, I first photographed it, then dumped the crayons out onto the floor, and ran my fingers through them. So I could retain just a little, I decided to save the purple ones. As Crockett Johnson’s biographer, that choice seemed a reasonable compromise.

But it’s hard to make reasoned compromises about irreplaceable things. My mother had saved my childhood drawings, in recycled manila envelopes, each labeled by year. I thought: well, I can’t save all of this – so, I’ll save representative samples. I put out most for recycling, but saved a few pieces of art created by me at 5 and 6 years old. Later, I thought: why not save more of these? I even went out to retrieve one drawing I’d thrown into the recycling bin. Now, I think: why not save them all? Had I kept them, these drawings would have taken up the space of a large art book. Maybe two.

In that moment, having no idea what I’d uncover, I was conscious mostly of limited time at mom’s house and limited space at home. So, I thought: better to be ruthless about this.

So many lost things. So few saved. But I’m grateful for these glimpses into the past, traces of that crayon line that extends from my childhood bedroom floor to my adult career. I’m also surprised by how much of what interested me then still interests me now. I’m four decades removed from that small boy who made those drawings. Yet I am also still that boy, dreaming that art can transform the world.

Charles Hatfield