This fall, I am teaching English 545: Literature for Adolescents on-line for the first time. That is, this is the first time I’m teaching the course on-line. It’s the umpteenth time I’ve taught the course, and the second time I’ve taught on-line.

One thing I learned from teaching on-line this past spring:Â Build the entire course before the term begins. And, yes, I learned that because I failed to do it. So, I am building it now. This week, I finished the curriculum for the first two weeks. In case others may find it useful, I’m sharing that below. (Scroll down.)

A word or two about what’s not in this blog post. Missing are the ensuing discussion, my responses to students’ responses, quizzes, my responses to the quizzes, the full syllabus, and resources on the course’s Canvas site. In other words, this is a partial representation of those first couple of weeks.

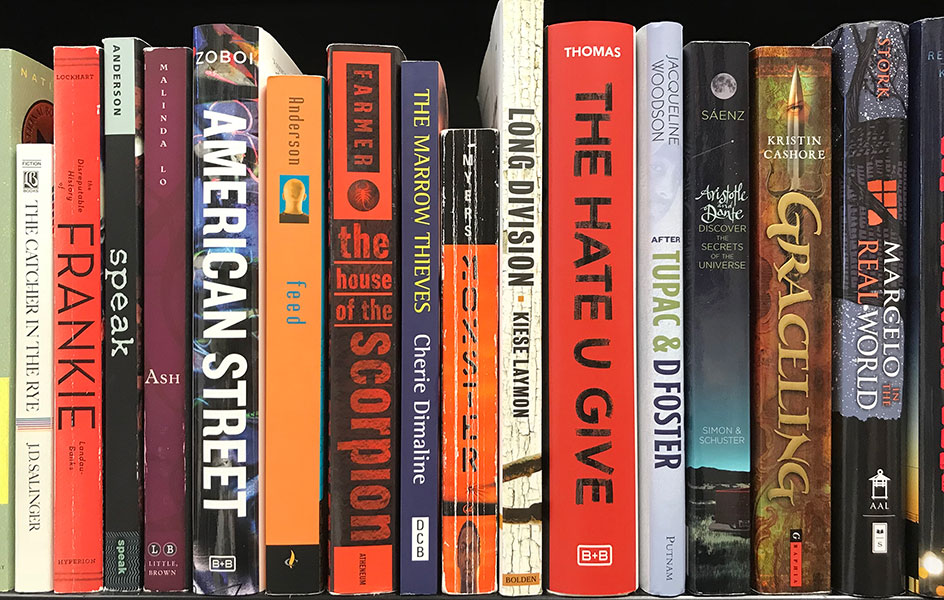

Here are the main literary texts we will read:

- Laurie Halse Anderson, Speak.

- M.T. Anderson, Feed.

- Kristin Cashore, Graceling.

- Cherie Dimaline, The Marrow Thieves.

- Nancy Farmer, The House of the Scorpion.

- Kiese Laymon, Long Division.

- E. Lockhart, The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks.

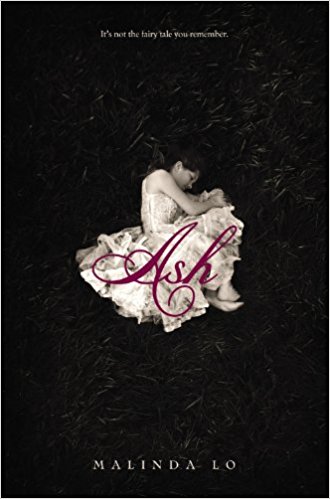

- Malinda Lo, Ash.

- Walter Dean Myers, Monster.

- Benjamin Alire Saenz, Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe.

- J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye.

- Francisco X. Stork, Marcello in the Real World.

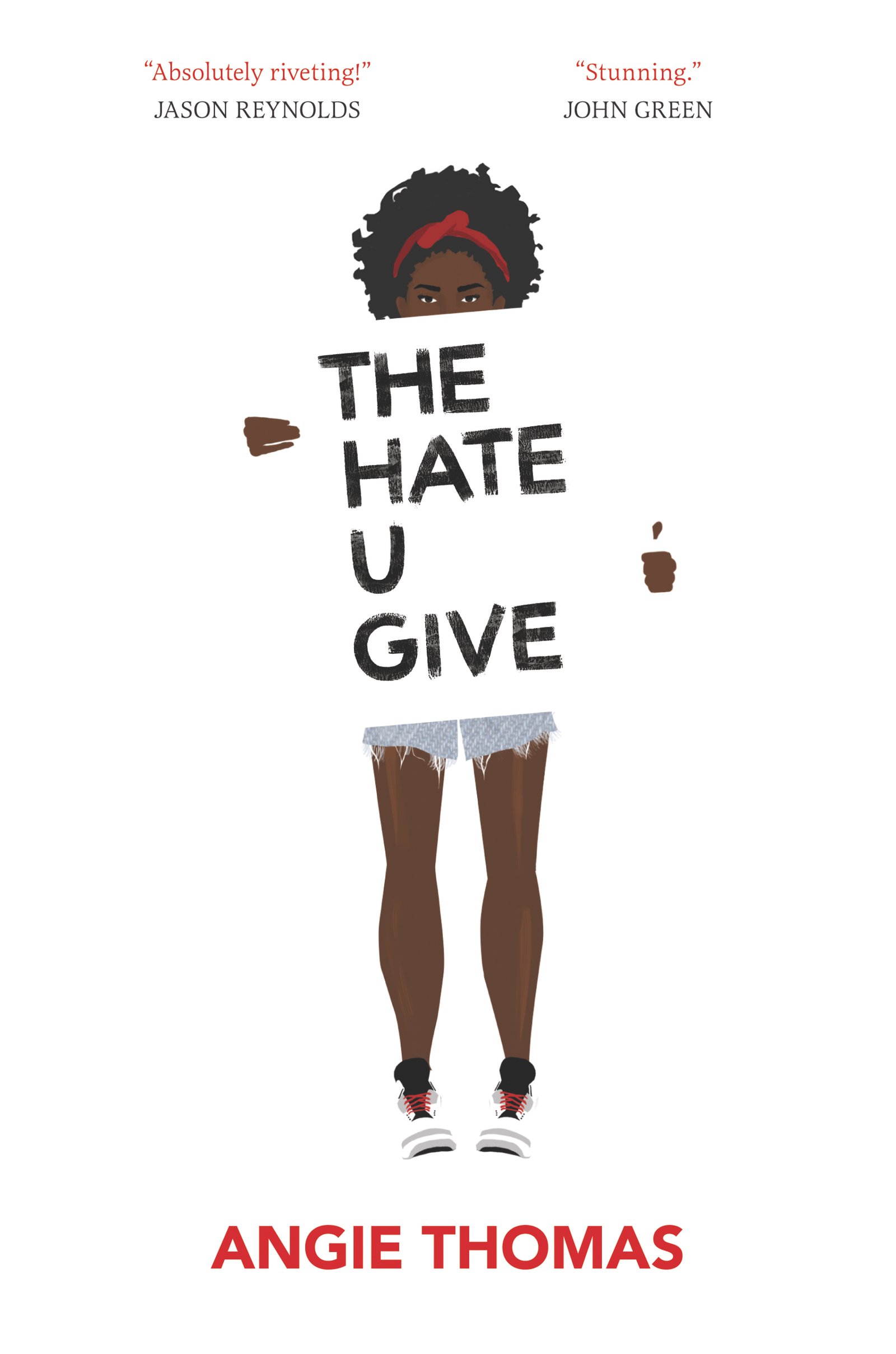

- Angie Thomas, The Hate You Give.

- Jacqueline Woodson, After Tupac & D. Foster.

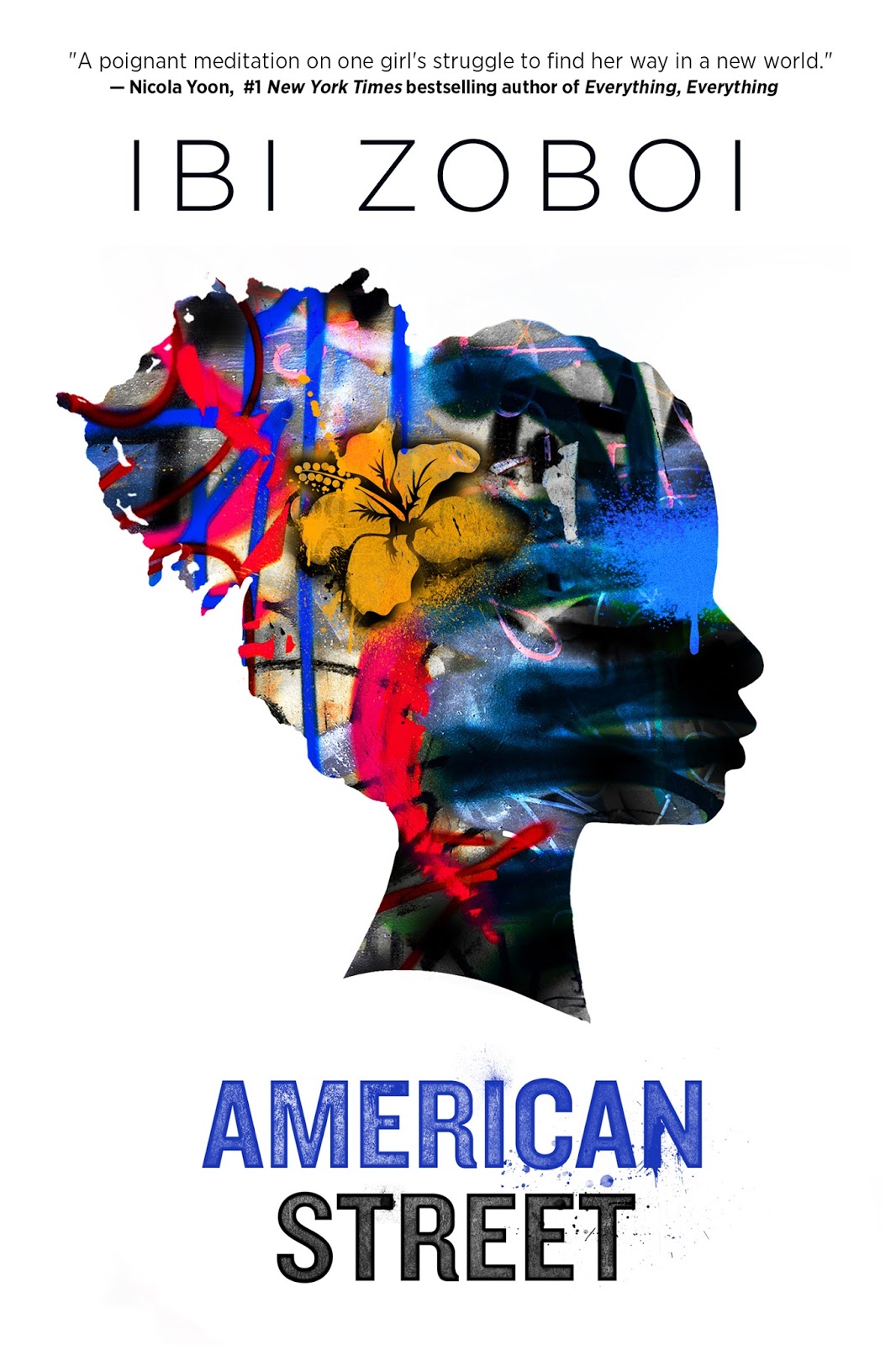

- Ibi Zoboi, American Street.

There will also be a few versions of “Cinderella” (both in preparation for Malinda Lo’s Ash and to get students thinking about the “YA” in many fairy tales), and a few secondary texts, all of which I will either link to or provide a pdf (available via Canvas). I’m really excited about the novels, three of which are from 2017 – and thus I’m teaching them for the very first time. I’m also teaching Ash (2009) for the first time.

|

|

|

|

I never teach a class exactly the same way twice. I’m always trying to improve. Now that I’m teaching on-line, I am also trying to improve my skills as a creator of videos! That learning curve is represented below: the second video is (I think) the weakest, and video #1 has some strengths but needs snappier editing. By three and four, the edits are improving. And the fifth (the first one on E. Lockhart’s Frankie Landau-Banks) is the best thus far.

WEEK 1

week #1, discussion #1: Intro.

I’ll repeat the questions from the video below.

1. What’s your name? And what do you prefer to be called?

2. Where are you from? And where are you located now, while you’re taking this class?

3. Here are our course’s objectives. Listen to them because at the end, I will ask you (A) which of our course objectives are you most looking forward to meeting? And (B) which objective do you think will be the most challenging for you?

This class will introduce you to a range of literature for adolescents, and develop your critical skills in reading these works. We will study works that feature adolescent characters, depict experiences familiar to adolescents, and are taught to or read by adolescents. We will approach these works from a variety of critical perspectives (including formalist, psychoanalytic, queer theory, feminist, Marxist, historical, postcolonial, ecological) — perspectives that many high schools want their teachers to know. In summary, this course will be about different kinds of literature read by young adults, approaches to thinking about this literature, and adolescence’s relationship to power. We will develop these skills via writing a once-weekly journal, participating in class discussions, taking a weekly quiz, and completing these and any other assignments on time.

Now that you know the course’s objectives, (A) which of our course objectives are you most looking forward to meeting? And (B) which objective do you think will be the most challenging for you? (C) Do you have any other objectives? If so, please list them.

4. Your adolescence is very likely far more recent than mine. And yet I know that high school and college are different – that you have very likely changed at least a little since high school… and possibly quite a lot. So, my third question is this. Describe your adolescence in one word. And why do you choose that word to describe your adolescence? The why is important.

5. Have you taken an on-line class before?

Format for answer: VIDEO

week #1, discussion #2: Adolescence, YA Literature, and… J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (through Chapter 10)

Part I: Adolescence & YA Literature

Repeating (below) the questions from the video (above) –

1. What is adolescence?

2. What are the social characteristics of adolescence?

3. Drawing on Lee Talley’s essay, what is “Young Adult”?

Format for answer: TEXT

Part II: J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye (1951), through Chapter 10

Those two questions I asked you on day 1 – now is the time to answer them.

1. On page 1, Holden tells us “I had to come out here and take it easy.” Where is here? From where is he narrating this story? And how do you know? Beyond the quotation I called your attention to, offer a supporting quotation or quotations from the text that tells you where he is when he is telling the story (as opposed to where he is when it happens).

2. Once more, M.H. Abrams’ classic definition of the unreliable narrator:

The fallible or unreliable narrator is one whose perception, interpretation, and evaluation of the matters he or she narrates do not coincide with the implicit opinions and norms manifested by the author, which the author expects the alert reader to share. (A Glossary of Literary Terms, 6th ed., p. 168)

And… I asked you to track Holden’s unreliability. So. offer a couple of examples where you see the narrator’s perception in tension with those “implicit opinions and norms” of the book.

Format for answer: TEXT

Questions to think about for next class (not this one) –

1. Symbols! This is why English teachers like the book. Holden keeps returning to ideas and objects that he invests with significance – this is how he conveys his emotional truths. The red hunting hat. The question of where the ducks go in the winter. The “Little Shirley Beans” record. Childhood (his own and his sister Phoebe’s). And, of course, the title of the novel itself. So, my question is this: track a symbol. Where does it recur and why? That is, what does it mean?

2. By the end of the novel, what (if anything) has Holden learned? And what’s next for Holden?

3. In addition to finishing the novel, I’ve also asked you to read my “7 questions we should ask about children’s literature.” Pay particular attention to the first of those 7 – What does this book present as normal? Apply that question to the novel, following up with these more specific questions that I have borrowed (and slightly modified) from Nathalie Wooldridge:

- What or whose view of the world, or kinds of behavior does the book present as normal?

- Why is the book written from this perspective? How else could it have been written?

- Â What assumptions does the book make about age, gender, race, class, sexuality, and culture (including the age, gender, race, class, sexuality, and culture of the reader)?

- Whose perspectives does the book present? Whose perspectives does the book silence or ignore?

4. Why has this novel become such a cultural touchstone? Should it be a cultural touchstone? Indeed, should it be on this syllabus? That last question is not a trick question. First of all, I’m always changing this syllabus, and I don’t always include The Catcher in the Rye. Second, you should question what’s on this syllabus. For this class, there are millions of books to choose from. Should Catcher in the Rye be among these 15?

Again, these last 4 questions are for next time.

week #1, discussion #3: J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (to end)

Answer the question that corresponds with your group number. Post your comment, drawing on examples from the book – remember the importance of close reading. Quote from the text to support your arguments. And then please respond to at least one other person in your group – ideally to two or three. Post your initial comment before the due date (end of Friday) for this discussion. If your responses to others’ occur after that, it’s OK – the discussion will still be enter-able for a week after the due date. Try to chime in as soon after the deadline as you can. I realize that we are all having a conversation asynchronously. Do your best.

1. As I say, I think all the symbols are why English teachers like the book. Holden keeps returning to ideas and objects that he invests with personal significance – this is how he conveys his emotional truths. He’s not likely to say, directly, “I’m afraid of adulthood” or “I miss my brother Allie” or “I feel vulnerable.” No, he’s going to put on his red hunting hat. He’s going to wonder about where the ducks go in the winter. He’s going to search for and then carry around the “Little Shirley Beans” record. He’s going to talk about childhood (his own and his sister Phoebe’s). And, of course, his fantasy of becoming a catcher in the rye. So, I asked you to track a symbol. Where does it recur and why? That is, what does it mean?

2. By the end of the novel, what (if anything) has Holden learned? And what’s next for Holden? Holden talks about wanting to be a catcher in the rye: “Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around — nobody big, I mean — except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff” (173). He talks about pretending he’s a deaf mute, living in a cabin near the woods (198-99, 204-05). He tries to erase all of the fuck yous realizes he can’t: “If you had a million years to do it, you couldn’t rub out even half the ‘Fuck you’ signs in the world. It’s impossible” (202). People keep “asking me if I’m going to apply myself when I go back to school next September. It’s such a stupid question, in my opinion. I mean how do you know what you’re going to do till you do it? The answer is, you don’t. I think I am, but how do I know? I swear it’s a stupid question” (213). That he asks himself this question at the end tells us what? Will he apply himself? Will he follow Antolini’s advice to learn from other writers?

3. So, I also asked you to read my “7 questions we should ask about children’s literature” and to pay particular attention to the first of those 7 – What does this book present as normal? Apply that question to the novel, following up with these more specific questions borrowed (and slightly modified) from Nathalie Wooldridge:

- What or whose view of the world, or kinds of behavior does the book present as normal?

- Why is the book written from this perspective? How else could it have been written?

- What assumptions does the book make about age, gender, race, class, sexuality, and culture (including the age, gender, race, class, sexuality, and culture of the reader)?

- Whose perspectives does the book present? Whose perspectives does the book silence or ignore?

I am asking you these questions because I want you to think critically about this novel and all novels we read. You do not need to agree with or like or enjoy each novel on the syllabus. I ask that you make an attempt to understand each work, but I also invite you – I encourage you – to raise critical questions about each work – backing up your critique with examples from the book.

4. Finally, a big question: Why has this novel become such a cultural touchstone? Should it be a cultural touchstone? And should it be on this syllabus? As I said last time, that question is not a trick question. (1) I’m always changing this syllabus, and I don’t always include The Catcher in the Rye. (2) You should question what’s on this syllabus. Of the millions of Young Adult books we could read, should Catcher in the Rye be among the mere 15 on the syllabus? Key here as in all questions is defending your answer with examples from the book.

Format for answer: TEXT

Don’t forget: journal entry due Sunday night!

Next time: E. Lockhart’s The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks. Its placement next on the syllabus is not accidental. So, you might consider her novel as being in conversation with Salinger’s novel. What would Lockhart’s book say to Salinger’s book? Each book features a protagonist inclined to rebel – against what does each protagonist rebel? And what does each protagonist accept? You might compare/contrast a bit as you read.

WEEK 2

week #2, discussion #1: E. Lockhart’s Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks (2008), through “Broken Date”

1. Let’s start with an exercise in close-reading. How does the novel’s opening letter position you, the reader? (Read the letter that opens the novel.)

A. What are the key words or phrases in that opening letter? Why?

B. What questions does the letter raise about the novel you are about to read?

C. What clues does the letter give you for the novel that you are about to read?

D. And where does the letter position you in relation to the novel’s main character, Frankie Landau-Banks? What sort of relationship does it invite? Are you sympathetic? Unsympathetic?

Sketch out some answers to these questions, referring to specifics in that opening letter – actually quoting them – in your response. Feel free to refer to moments beyond that opening letter, too.

2. What questions does Frankie (and the novel itself) raise about masculinity and femininity? That is, how might it invite us to think critically about the gender roles that we’re encouraged to inhabit – “acceptable” versions of masculinity and femininity? Point to a few examples. And one last question for part 2 of our discussion: If she landed in The Catcher in the Rye or he landed in her novel, what would Frankie say to Holden?

3. What is the panopticon? How does it work as a system of control? And… what might it tell us about adolescence – or, if you like, about Frankie?

Don’t forget to cite specifics from the novel in your answers!

Format for answer: TEXT

week #2, discussion #2: E. Lockhart’s Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks, to end

1. Here is a more succinct version of this question than what’s included in the video: Does the novel propose the idea that women/girls and men/boys use power differently? In what ways might it be helpful to think of power as distinctly gendered? In what ways might that not be helpful to understand power as gendered?

Here is the longer version, which I offer mostly for the citations therein. Several times, Frankie notes how the Loyal Order of the Bassett Hounds – that bastion of patriarchal privilege – fosters bonding, “togetherness,” “connection” (see pp. 195, 221, 222). She longs for such a bond herself… but doesn’t get one. At the end, we learn that, while Trish is a “loyal friend,” “Trish’s lack of understanding is a condition of that loyalty” (338). Does Frankie’s lack of a female cohort undermine the feminist critique of patriarchy, expressed elsewhere in the novel? Is it positing that women’s power works differently (a version of Elizabeth’s argument in the debate, pp. 160-165)? If so, does that difference contradict Frankie’s frequent critique of the “double standard” she faces as a girl? Or, whether it is or is not contradictory, might it be positing an alternate form of power?

2. Near the end of the novel, Porter asks, “Why did you do all that, Frankie?” She answers his question with two questions: “Have you ever heard of the panopticon?” And “Have you ever been in love?” (329). What do these two questions tell you about her motivations? And why do you suppose Lockhart does not have Frankie elaborate? Finally, how might these two questions influence our interpretation of the novel?

3. E. Lockhart has said that there will be no sequel to this novel. Her narrator, however, does offer two possibilities for Frankie’s future (336-337): “They sometimes go crazy, these people” or they “change the world” (337). Defending your answer with examples from this book, which future is more likely? Make sure you refer to the final chapter.

Please respond to at least one other comment in your group. As before, post your initial comment before the deadline; your second (and third, etc.) can fall after the deadline.

Format for answer: TEXT

Don’t forget: journal entry due Sunday night, and quiz due Monday night.

For next week, we’re reading Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak (1999). Talk to you then!

Incidentally, I’ve been posting these on YouTube because the Hale Library fire knocked our course infrastructure system (Canvas) for a loop. Its video-sharing apparatus (MyMediaSite) hasn’t been working. So, I decided to use my YouTube channel. I haven’t yet decided if I will post all Literature for Adolescents course videos on YouTube… or just do so until the university’s Canvas site stabilizes again.*

The main downside is that students will be able to see the videos far ahead of two weeks in advance. Following the advice of other on-line teachers, I make visible curriculum for only two weeks into the future. The philosophy behind that is you don’t want a student to rush through the class. They should proceed at roughly the pace of the semester, learning as they go, improving their discussion responses etc. in response to feedback from me and other students. Showing them two weeks into the future allows them to better manage their time – and work ahead if their schedule demands that.

The upside is the possibility that these videos might be useful to other teachers or students of Literature for Adolescents. If you do find any of these useful, let me know. Also, if you spot any mistakes or have suggestions, let me know – though keep in mind that you are not seeing all of the teaching. I will be joining the students’ discussion – typically via text, though sometimes via video. And my responses to their discussion will sometimes result in additional readings – always brief ones, but useful ones.

That’s all for now.

* A public thanks to everyone working in K-State’s ITS, Telecommunications, and all who have been putting in long hours to get the university fully on-line again. I appreciate it! And so do my fellow faculty members!

Meg

Philip Nel