Good afternoon. Thanks for coming. Thanks to Susan Kemper for organizing this, and to KU for hosting.

I’m @philnel on Twitter. The Board of Regents is @ksregents. And the hashtag for this conference is #FreeSpeechKS. If you Tweet, feel free to tag us. In case there are any Regents unable to attend, I will periodically live-Tweet my talk, and post the full text when I finish.

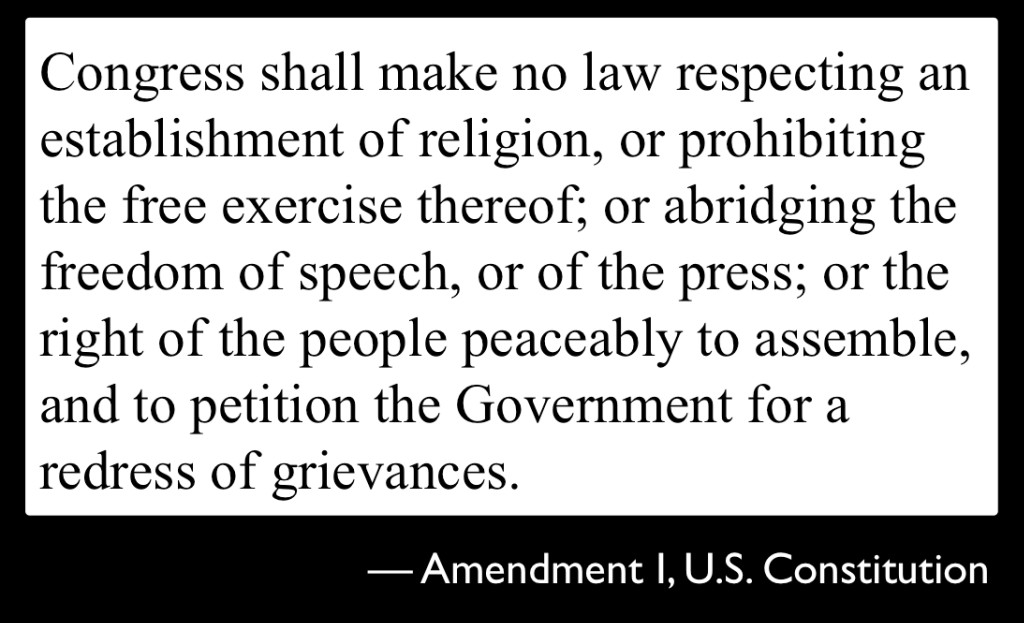

I open with that because everything I am saying now is protected under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. It’s protected whether I say it in this room, on a blog, via social media, or directly to Regents Chairman Fred Logan. What we are all doing here today is asserting our rights as U.S. citizens to speak, without fear of censure.

I also open with that because what we are doing here is asserting our rights, as scholars, to academic freedom. As the AAUP’s 1940 Statement on Academic Freedom reminds us,

Institutions of higher education are conducted for the common good…. The common good depends upon the free search for truth and its free exposition. Academic freedom is essential to these purposes and applies to both teaching and research. Freedom in research is fundamental to the advancement of truth. Academic freedom in its teaching aspect is fundamental for the protection of the rights of the teacher in teaching and of the student to freedom in learning.

This fundamental principle is under attack – and not just in Kansas, but in South Carolina, Tennessee, Michigan, Colorado, and many other places. Across the country, opponents of freedom of speech are trying to quash intellectual inquiry, to prevent educators from doing their jobs, and to take away their basic rights as citizens.

Now, of course, that’s not how they put it. They offer different reasons. A state legislator in Michigan has threatened to take $500,000 away from Michigan State University’s budget because the university has a few courses on labor unions. According to him, even to talk about the subject would “encourage labor disputes.” Meanwhile, Tennessee Senator Stacey Campfield didn’t like the University of Tennessee’s student-run Sex Education Week – which included speakers from a range of perspectives, including clergy, and proponents of abstinence education. So, he proposed legislation forbidding the university from using any of its money on any invited speakers. This would shut down even commencement speakers, even anyone who came for free but received travel reimbursement. Senator Campfield’s reasoning? Teaching about sex didn’t promote “diversity of thought.”

And, as it so often does, South Carolina has embraced political recklessness with the greatest fervor. This year, its legislature cut $52,000 from the College of Charleston’s budget because – as a voluntary, summer read – the college recommended Alison Bechdel’s award-winning Fun Home, a lyrical, beautiful memoir about her own coming out and her relationship with her closeted gay father. State representative Garry Smith alleged that recommending the book was a form of, and I quote, “academic totalitarianism,” because it “promoted” homosexuality. Also this year, the College’s Board of Trustees ignored the recommendations of the College’s search committee, and instead appointed as the College of Charleston’s new president, Lt. Governor Glenn McConnell, a man so nostalgic for the Confederacy that he likes to dress up as a Confederate general and opposed attempts to remove the Confederate flag from the statehouse grounds.

And, as it so often does, South Carolina has embraced political recklessness with the greatest fervor. This year, its legislature cut $52,000 from the College of Charleston’s budget because – as a voluntary, summer read – the college recommended Alison Bechdel’s award-winning Fun Home, a lyrical, beautiful memoir about her own coming out and her relationship with her closeted gay father. State representative Garry Smith alleged that recommending the book was a form of, and I quote, “academic totalitarianism,” because it “promoted” homosexuality. Also this year, the College’s Board of Trustees ignored the recommendations of the College’s search committee, and instead appointed as the College of Charleston’s new president, Lt. Governor Glenn McConnell, a man so nostalgic for the Confederacy that he likes to dress up as a Confederate general and opposed attempts to remove the Confederate flag from the statehouse grounds.

These are only a few examples of recent attacks on academic freedom.

But my point is: We in Kansas are not alone. Others are fighting this fight, too.

The reasons for these attacks differ. In the case of South Carolina, it’s ordinary bigotry –against gay people, and against people of color. In Tennessee, ignorance also motivates the censor. In Michigan, it’s explicitly anti-labor, enforcing a curriculum designed to create compliant workers, rather than engaged, inquisitive citizens.

Ideologically, Michigan’s censors are closest to Kansas’s censors – both see the university not as a place for intellectual inquiry, but as a business that produces future employees. The Kansas Board of Regents views Kansas universities as poorly managed credentialing factories. The Regents are the new management, here to tell us how we should do our jobs, advising us not to step out of line, to just keep producing the diplomas that customers – excuse me, students – are paying for.

This is why the Board of Regents always justifies their policy by telling us: It’s legal. We’re lawyers. We’ve checked the Constitutionality of this, and it’s legal.

This is why the Board of Regents always justifies their policy by telling us: It’s legal. We’re lawyers. We’ve checked the Constitutionality of this, and it’s legal.

To that, I have four responses. First, if you actually have to check the constitutionality of your social media policy, then you’re aware that the policy is so extreme … that people are going to tell you “This is unconstitutional.”

Second, while it’s worthwhile to investigate the legality of this policy, why is that the only question they seem to be asking? Why not ask: Is this good for higher education in Kansas? That, after all, is their job as Regents – to advocate for higher education in Kansas.

Third, they don’t ask these questions because the Kansas Board of Regents see a university as just another corporation. But a university is different from a corporation. People who work for universities exchange ideas because it’s our job to exchange ideas. Debate, dissent, discussion – freedom of inquiry – are at the core of what the academic enterprise is all about.

Fourth – and this is a longer point – historically, new forms of media have always been the targets of censors. And, historically, the censors have always failed. History tells us that if the Board of Regents attempts to uphold any version of their current policy, then they will ultimately fail.

There are many reasons why they will fail, the first of which is that powerful ideas – like freedom of speech – are stronger than the state, more enduring than any who would suppress them. Socrates questioned the wisdom of the Athenian state. It sentenced him to death by drinking a mixture containing hemlock. We do not remember the people who tried to censor (and ultimately killed) Socrates, but we still remember Socrates and his ideas – among them, the Socratic method of asking questions to help us arrive at a deeper understanding. I use this method in my classes every day, and I expect many other teachers here use it as well.

In the seventeenth century, when the British Parliament sought to replace one means of censorship with another, John Milton wrote one of the most eloquent defenses of freedom of speech. Replacing the Star Chamber, Parliament’s Licensing Order of 1643 said that any publications deemed offensive to the government could be seized and destroyed, and writers, printers, and publishers of such works could be arrested and jailed. In words that speak directly to our current situation, Milton’s Aeropagitica (1644) criticized this law:

how can a man teach with autority, which is the life of teaching, how can he be a Doctor in his book as he ought to be, or else had better be silent, whenas all he teaches, all he delivers, is but under […] the correction of his patriarchal licencer to blot or alter what precisely accords not with the hidebound humor which he calls his judgement. […] I hate a pupil teacher, I endure not an instructer that comes to me under the wardship of an overseeing fist.

That’s exactly the problem here. We cannot teach “under the wardship of an overseeing fist.” We need to be able to share ideas – such as this quotation, which comes from my colleague, Blake scholar Mark Crosby.

As the flames of the French Revolution ravaged Paris a century and a half later, the British government was again worried – this time, worried that challenges to monarchy would jump the English Channel. So, they enacted repressive legislation against the freedom to publish an opinion. This culminated in the famous 1794 treason trials, in which the British government prosecuted people for imagining. To write or to think about the end of monarchy, you have to imagine the death of the king and so, according to the government, be engaged in a treasonable act. The defense successfully argued that the only people imagining the king’s death were the prosecution.

As the flames of the French Revolution ravaged Paris a century and a half later, the British government was again worried – this time, worried that challenges to monarchy would jump the English Channel. So, they enacted repressive legislation against the freedom to publish an opinion. This culminated in the famous 1794 treason trials, in which the British government prosecuted people for imagining. To write or to think about the end of monarchy, you have to imagine the death of the king and so, according to the government, be engaged in a treasonable act. The defense successfully argued that the only people imagining the king’s death were the prosecution.

One of the pieces of writing that emerged from this period (and, again, thanks to Mark Crosby for pointing me to it), William Godwin’s Political Justice (1793) offered this vigorous and eloquent defense of freedom of speech that offers guidance to us today:

No government ought … to resist the change of its own institutions; and still less ought it to set up a standard upon the various topics of human speculation, to restrain the excursions of an inventive mind. It is only by giving a free scope to these excursions that science, philosophy and morals have arrived at their present degree of perfection, or are capable of going on to that still greater perfection.

This is what the Regents resist understanding: “the excursions of an inventive mind” – and “giving a free scope to these excursions” – is the purpose of higher education. In restraining these excursions, the Regents attack our core mission.

So. What to do? In Tennessee, people protested, and, in the face of strong opposition, Senator Campfield’s bills died after he failed to bring them up for a vote prior to the deadline. In South Carolina, the College of Charleston’s student government and faculty senate have voted no confidence in their Board of Trustees. Students and faculty have taken to the streets. This past Monday, the cast of the Off-Broadway musical adaptation of Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home performed scenes from the play at the College.

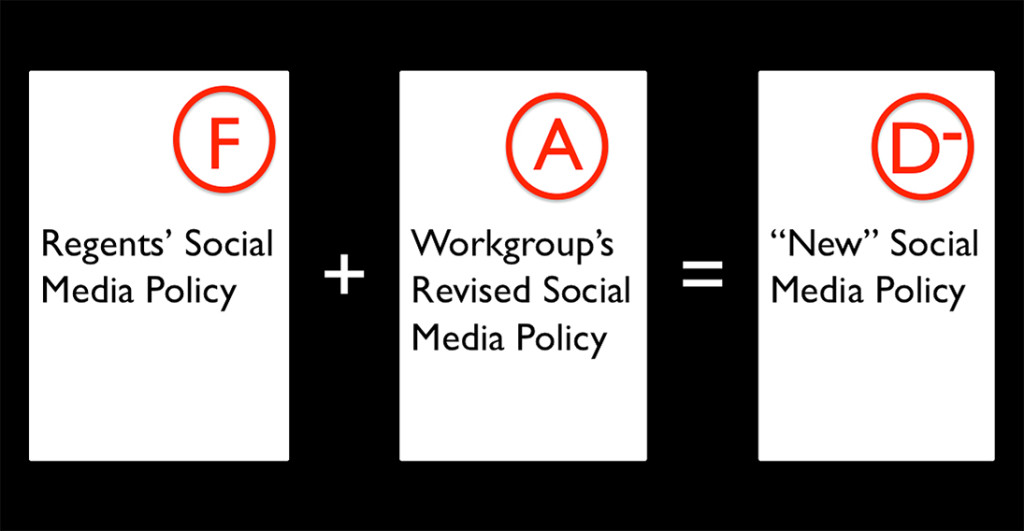

Here, at their May meeting, the Board of Regents will, I think, present a “revised” policy that adds language affirming academic freedom to a policy that otherwise eviscerates academic freedom. They will present this incoherent policy as a compromise, deliberately ignoring the fact that when you add pieces of an “A” policy (the work group’s revision) to an “F” policy (the Regents’ original) you do not magically transform that “F” into an “A.” You get, maybe, a “D-.”

In response, I propose that we: (1) say that we have no confidence in the Kansas Board of Regents’ leadership, (2) demand that they resign, and (3) call for reform in how Regents are selected. Selecting a regent should not be an act of political patronage. People who oversee higher education should actually know something about higher education. I would not presume to tell Regent Logan how to run his law firm — because I have no background in law. And yet Mr. Logan presumes he knows what’s best for higher education. Logan and the Regents’ aggressive indifference to the recommendations of the work group, their condescension towards the faculty, staff, and students that they ostensibly oversee is a clear signal that they have no business serving as Regents.

But we need to do more than this. We need to challenge the pervasive argument that education should follow a business model. Higher education provides a public good. We must, as Thomas Jefferson wrote, “Educate and inform the whole mass of the people. They are the only sure reliance for the preservation of our liberty.” That is the purpose of higher of education. And it is the purpose that our current regents reject.

The Board of Regents don’t seem to care that their repressive policies threaten the ability of Kansas universities to attract the very best faculty. After all, given the current academic job market, Kansas universities will still find people to staff the classes. Sure, they may not be the best – but so what? Diminishing the value of a Kansas university degree does not trouble the Regents because they have no interest in research. They simply want to funnel as many paying customers (“students”) as they can through the credential-granting business (“university”). Because you measure the value of a university by how many degrees it grants, don’t you?

That attitude is dangerous. It threatens not just higher education, but the republic itself. Education is not just about producing diplomas. It is about thinking. It is about challenging assumptions. It is about nurturing an informed citizenry who are willing to challenge the assumptions of those who govern them. It is about making people uncomfortable, in ways that may impair harmony among co-workers, or discipline by superiors – in ways that may not be in the “best interest” of whomever is running a university at any given time. A university is about precisely what the Board of Regents’ social media policy prohibits.

So. It’s time for these Regents to step down. And it’s time for Kansans to fight back.

This is the full text of the talk I gave today, at Academic Freedom and Responsibility in the Age of Social Media, a symposium held the University of Kansas. The conference hashtag: #FreeSpeechKS.

Toni Tadolini

Elizabeth Dodd

Misty Anderson

Christina Hauck

Cora Cooper

Pingback: Still Teaching the Work | Teaching_the_Work