In the 58 years since its publication, Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon has appeared in 14 languages, and inspired many artists. This blog (which takes its name from a line in the book) presented The Purple Crayon’s Legacy, Part I: Comics & Cartoons… nearly three years ago. It is at last time for Part II: Picture Books.

Anthony Browne, Bear Hunt (1979)

As Harold does, Bear goes for a walk. As Harold does, Bear carries something to write with (a pencil instead of a crayon). And, as is the case with Harold, what Bear draws becomes real. It’s true that, graphically, this is a very different book. Browne’s jungle scenes – all in color – recalls those of Henri Rousseau. Also, where Harold both creates and solves his problems, Bear’s problems – two hunters who want to shoot him – are not imagined. Fortunately, his pencil proves more powerful than their guns. I’m tempted to say that, in the book, the power to imagine a better reality trumps the power to kill. However, Browne handles this story with such a light touch that, while it may suggest such morals, that’s not the focus.

Jon Agee, The Incredible Painting of Felix Clousseau (1988)

Felix Clousseau’s art looks ordinary, but it’s not. His painting of a duck actually quacks. However, “that was only half of it,” observes Agee’s narrator as the duck leaves the painting. This is one of the book’s sly jokes (if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck…), which include comic names of rival painters (such as Felicien CaffayOllay), several Magritte references, and the pun on the final page. No, I won’t give away the ending. Read it yourself.

Chris Van Allsburg, Bad Day at Riverbend (1995)

In his Caldecott acceptance speech for Jumanji (1981), Chris Van Allsburg actually thanked “Harold, and his purple crayon.” He has elsewhere spoken of the book as the one he “remember[s] most clearly” from his childhood. Van Allsburg loved its theme of “the ability to create things with your imagination,” which, he says, is “a fairly elusive idea, but [the book] presents it so succinctly through these simple drawings that it registers very clearly.”

May of Van Allsburg’s books traverse (or blur) the line between imaginary and real, but Bad Day at Riverbend seems the most explicit homage to Johnson’s book. Rendered in coloring-book style, the people of Riverbend face a “greasy slime” that sticks aggressively to whatever it assaults. We readers recognize the “slime” as crayon scribbles, which (spoiler alert!) the book’s ending reveals to be true. The townspeople are … the victims of a child with a crayon.

Thacher Hurd, Art Dog (1996)

As Harold does, Art Dog creates art that changes physical realities. He also has his artistic adventures at night, beneath the moonlight. On one of the pages, he paints a somewhat goofy purple (with green spots) bird who reminds me of Harold’s drawings. Above the bird, on the wall, he has painted falling stars reminiscent of the one that Harold rides home in Harold’s Trip to the Sky (1957).

Some years ago, I wrote to Thacher Hurd to ask whether he or his parents (Clement Hurd and Edith Thacher Hurd) had known Johnson or Ruth Krauss. He said that they may have, though he had no memories of them. During our very brief email correspondence, I said “I’ve often thought that Harold would get along very well with Art Dog.” He responded, “Yes, I did put in a subtle aside to Harold and the Purple Crayon in Art Dog. I love that book, and loved it as a kid.”

Régis Faller, Voyage de Polo (2002: English translation: The Adventures of Polo, 2006) and its many sequels

Wordless (save for the occasional sound effect), Faller’s Polo books have an associative narrative logic that’s evocative of the Harold stories’ structure. In Voyage de Polo (The Adventures of Polo), he opens the door of his island tree home, walks over to a tightrope, and then starts carefully to make his way along it – shades of Harold’s tightrope act in Harold’s Circus (1959). The tightrope suddenly becomes stairs, which Polo then climbs – reminiscent of the stairs in Harold’s Fairy Tale (1957). Beyond those direct visual allusions (or, at least, they feel like allusions), the story’s art manages to link each panel to the next, and then to the next. You don’t quite know where Polo is going, but he’s traveling with a purpose, and fun to accompany for the duration of his journey. More than anything else, the chain of associations most strongly reminds me of Harold’s stories.

Delphine Durand, Bob & Cie., (2004; English translation: Bob & Co., 2006)

A small book that begins with “a blank page” and then waits for “the story” to get underway, Durand’s Bob & Cie. (Bob & Co.) pursues the metaphysical implications of Harold’s predicament. Except, in this story, it’s Bob’s predicament. It’s hard to summarize. By turns whimsical and profound, Durand’s absurdist metafiction is about faith, narrative, the universe, beginnings and endings. It’s one of my all-time favorite books. Someday, I’d like to write (a blog post? an essay?) about Durand’s work. Her sensibility and sense of humor appeal to me.

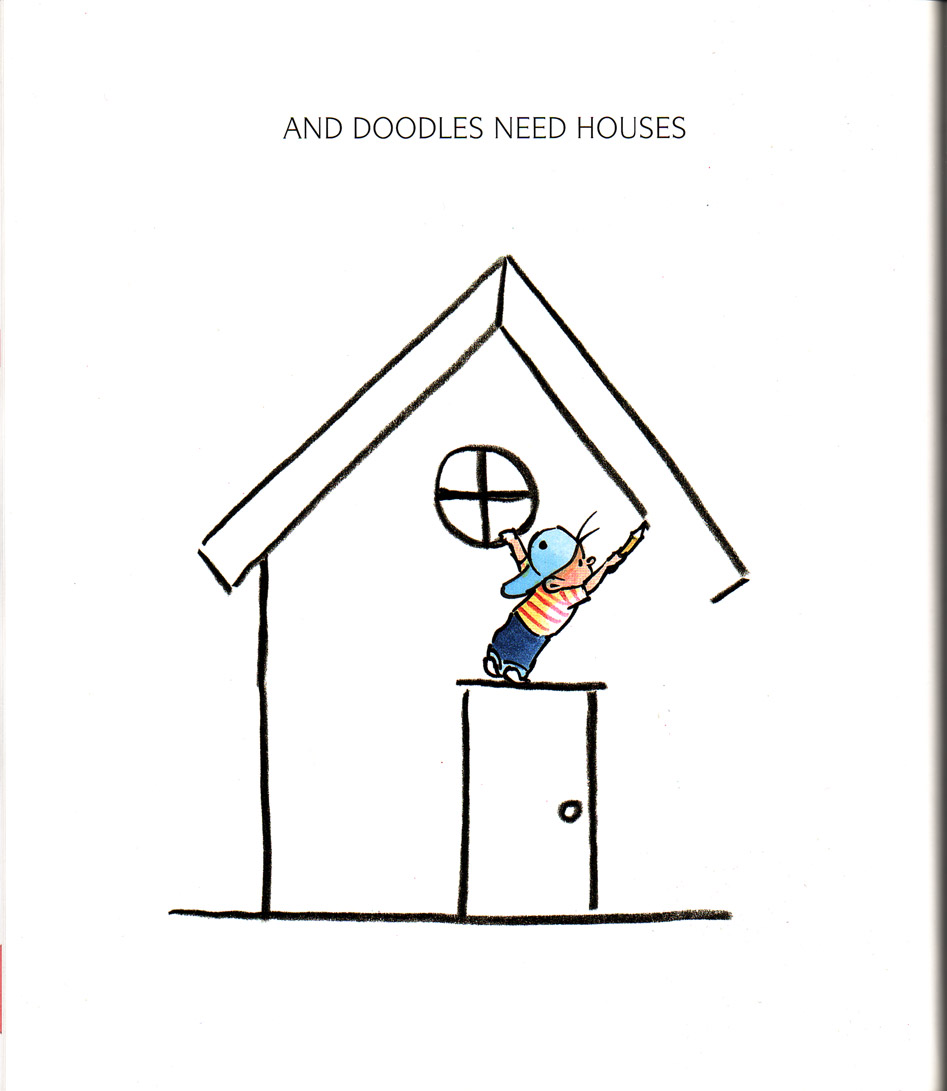

Patrick McDonnell, Art (2006)

The creator of the comic strip Mutts creates a story about a boy named Art who creates lots of art. This conceit inspires many puns on the name, and, well, lots of art (and Art). About a third of the way in, the book moves explicitly to Harold’s territory, when Art draws a house and then stands on the doorway in order to draw the roof.

Deborah Freedman, Scribble (2007)

When Emma insults her younger sister Lucie’s drawing of a kitty (“It looks like a scribble”), Lucie defends herself: “It’s a special scribble-kitty!” In retaliation, she scribbles all over Emma’s drawing of the Princess Aurora. Emma storms off. Then Scribble, Lucie, and the sisters’ real cat step into the drawings – which is the moment that the book enters Harold’s realm. It’s telling that only the younger sister crosses the boundary from real to imaginary worlds. Perhaps Freedman is suggesting that only the youngest children – Lucie, Harold – can make that leap, and fully believe it. Freedman’s second book, Blue Chicken (2011), also plays with the boundary between art and life. But, this time, a chicken is the artist.

Allan Ahlberg & Bruce Ingman, The Pencil (2008)

A pencil (which appears itself to have been rendered in pencil) draws a boy, a dog, a cat, a house, a road, and a park. As in Harold and the Purple Crayon, all things the pencil draws are real. The book departs from Johnson’s book when the pencil draws a paintbrush, who in turn colors everything the pencil draws. The decision to add color bends the narrative logic (how can a grey pencil draw color?), as does the decision to add an eraser (how can an eraser remove watercolors?). But the eraser proves a valuable antagonist. Just as the pencil draws enthusiastically, so the eraser embraces his function – threatening the world that pencil and paintbrush have created. I wonder: what would have Harold done with an eraser? He does cross things out (the witch in Harold’s Fairy Tale, the whole picture in A Picture for Harold’s Room), but he never erases.

A pencil (which appears itself to have been rendered in pencil) draws a boy, a dog, a cat, a house, a road, and a park. As in Harold and the Purple Crayon, all things the pencil draws are real. The book departs from Johnson’s book when the pencil draws a paintbrush, who in turn colors everything the pencil draws. The decision to add color bends the narrative logic (how can a grey pencil draw color?), as does the decision to add an eraser (how can an eraser remove watercolors?). But the eraser proves a valuable antagonist. Just as the pencil draws enthusiastically, so the eraser embraces his function – threatening the world that pencil and paintbrush have created. I wonder: what would have Harold done with an eraser? He does cross things out (the witch in Harold’s Fairy Tale, the whole picture in A Picture for Harold’s Room), but he never erases.

Matteo Pericoli, Tommaso and the Missing Line (2008)

The line of the hill disappears from Tommaso’s drawing, which shows “a house on a hill, / a tall tree and some mountains. / And two people – / him and his grandma.” So, of course, he goes off in search of it. On the right-hand page, Pericoli uses black ink for everything, except his character’s drawing and specific lines that Tommasso finds – those are all in orange. On the left-hand page, Pericoli places white text on an orange background. The orange at left makes each orange line at right “pop” out of the picture. Visually, it’s very effective.

The line of the hill disappears from Tommaso’s drawing, which shows “a house on a hill, / a tall tree and some mountains. / And two people – / him and his grandma.” So, of course, he goes off in search of it. On the right-hand page, Pericoli uses black ink for everything, except his character’s drawing and specific lines that Tommasso finds – those are all in orange. On the left-hand page, Pericoli places white text on an orange background. The orange at left makes each orange line at right “pop” out of the picture. Visually, it’s very effective.

Sure, Tommaso is also an artist, but, you ask, is there a more particular connection to Harold and the Purple Crayon? There are several, first of which is that Tommaso does find his line – “as real as he always remembered it” – out in the world. So, as in Johnson’s book, art can become real. Also, though Pericoli’s line is not as tight as Johnson’s, the pen-and-ink drawings on white pages evoke Johnson’s aesthetic sensibility. Just as Harold’s purple line does, Tommaso’s orange line has as powerful a visual presence.

Any obvious (or not-so-obvious) books I’ve missed? I realize there are many other metafictional books (Scieszka and Smith’s The Stinky Cheese Man, Barbara Lehman’s The Red Book, to name but two) or aesthetically comparable books (Lehman, again, Newgarden and Cash’s Bow Wow series) or books about artists (Lionni’s Frederick, McClintock’s The Fantastic Drawings of Danielle). My list may be too narrow, but its idiosyncrasies will I hope inspire discussion. So, let the discussion begin!

Related Posts:

- The Purple Crayon’s Legacy, Part I: Comics & Cartoons (13 Sept. 2010)

- More Metafiction for Children (4 Sept. 2010)

(And, yes, I do plan further parts in this series – with luck, they’ll appear more swiftly than Part II! Indeed, the blog has been quieter for this past month because, this summer, I’ve foolishly taken on more writing than I can cope with. I’m struggling to keep my head [nearly] above water.)

jules

JoeyC

JoeyC

Philip Nel

Harold Underdown

Philip Nel

Pingback: Styling Librarian #IMWAYR It’s Monday What Are You Reading? | The Styling Librarian

Scope Notes

Katherine Tillotson

JoeyC

Philip Nel

amy koss

Debbie

Kate Slater

Pingback: Peter McCarty’s Jeremy and his Monster |

Rachael