As I look at the American Library Association’s lists of Banned and Challenged Books, one recurring theme emerges: most (though not all) depict difficulties faced by children and teens. Though the motive for banning books is protection, restricting access to these books hurts the children and teens who are most in need of them. Laurie Halse Anderson‘s Speak and Maya Angelou‘s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings both addresses the aftermath of rape. Harry Potter tells of a child who thrives despite the active neglect of his foster parents. Rudolfo Anaya‘s Bless Me, Ultima depicts the experience of facing peers who ridicule you for your culture and of facing parents more invested in their dreams than your own. Tim O’Brien‘s The Things They Carried and Walter Dean Myers‘s Fallen Angels depicts how war shapes a young psyche. Justin Richardson, Peter Parnell, and Henry Cole’s And Tango Makes Three shows that same-sex parents appear elsewhere in the animal kingdom, too. Alex Sanchez‘s Rainbow Boys depicts the challenges gay teens face.

As I look at the American Library Association’s lists of Banned and Challenged Books, one recurring theme emerges: most (though not all) depict difficulties faced by children and teens. Though the motive for banning books is protection, restricting access to these books hurts the children and teens who are most in need of them. Laurie Halse Anderson‘s Speak and Maya Angelou‘s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings both addresses the aftermath of rape. Harry Potter tells of a child who thrives despite the active neglect of his foster parents. Rudolfo Anaya‘s Bless Me, Ultima depicts the experience of facing peers who ridicule you for your culture and of facing parents more invested in their dreams than your own. Tim O’Brien‘s The Things They Carried and Walter Dean Myers‘s Fallen Angels depicts how war shapes a young psyche. Justin Richardson, Peter Parnell, and Henry Cole’s And Tango Makes Three shows that same-sex parents appear elsewhere in the animal kingdom, too. Alex Sanchez‘s Rainbow Boys depicts the challenges gay teens face.

Children in vulnerable populations need to read books that help them make sense of their experiences. As Mr. Antolini tells Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger‘s The Catcher in the Rye (another frequently challenged book), “you’ll find that you’re not the first person who was ever confused and frightened and even sickened by human behavior. … Many, many men have been just as troubled morally and spiritually as you are right now. Happily, some of them kept records of their troubles. You’ll learn from them – if you want to. … They tend to express themselves more clearly, and they usually have a passion for following their thoughts through to the end” (189). Or ,as Holden says earlier in the novel, “What really knocks me out is a book that, when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author was a friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it” (18).

Many of the books that have been banned or challenged are exactly the books that can be the friend to the young person who desperately needs to know that she or he is not alone, that other people have faced similar struggles. Though there are many such teens, I have been thinking a lot about the high suicide rate among gay teen-agers. (And, yes, Given Holden’s anxiety about “flits,” The Catcher in the Rye may not be the book to which gay teens turn.)

Dan Savage’s “It Gets Better” Project has strikes me as particularly effective because it lets GLBTQ youth know not only that they’re not alone, but also that the traumas of high school do end and life can be good and even wonderful at times.

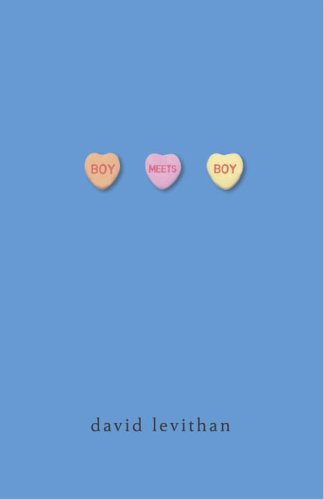

Of course, I’d much rather that young people lived in the world of David Levithan’s Boy Meets Boy, where teen-agers are allowed to express their sexual preference without fear of bullying. But we don’t live in that world. In the past three weeks, bullying has led to the suicides of Tyler Clementi, Seth Walsh, Asher Brown, Billy Lucas, and others whose deaths have not made headlines. It’s extremely hard for teen-agers to realize that life can get better for them. Videos like this can help.

Of course, I’d much rather that young people lived in the world of David Levithan’s Boy Meets Boy, where teen-agers are allowed to express their sexual preference without fear of bullying. But we don’t live in that world. In the past three weeks, bullying has led to the suicides of Tyler Clementi, Seth Walsh, Asher Brown, Billy Lucas, and others whose deaths have not made headlines. It’s extremely hard for teen-agers to realize that life can get better for them. Videos like this can help.

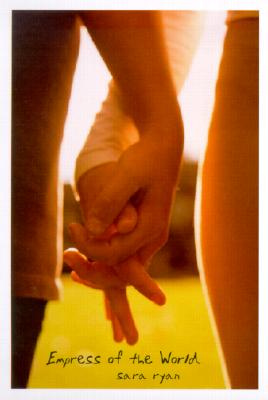

I think that books can help, too. In my Literature for Adolescents class, I teach Francesca Lia Block’s Weetzie Bat and Sara Ryan’s Empress of the World. I teach the former for its frank depiction of sexuality, but also its magical realism, its lyrical prose, and its influence on later writers… such as Sara Ryan, who alludes to Weetzie in her novel. I teach her Empress of the World because – in addition to being a well-written narrative – I find that my students are more likely to teach it than Weetzie Bat. They’re able to appreciate Weetzie Bat as art, but the conception of Cherokee Bat makes some uncomfortable. Since many will go on to be high school teachers, I want them to have a book about gay teens that they feel comfortable teaching.

Since many will go on to be high school teachers, I want them to have a book about gay teens that they feel comfortable teaching.

(Incidentally, I’m definitely open to other suggestions for other gay-friendly books for that “slot” on the syllabus. Each time I teach the class, I change it a little, swapping out some books, adding new ones, and so on. So… if you have suggestions, please place them in the comments below.)

High school can be a difficult time – especially if you’re a member of any group that’s mocked, bullied or ridiculed for being “different.” It’s hard enough growing up knowing that, say, your government believes that your sexuality makes you unfit to serve your country in uniform. Or growing up knowing that you need to keep your love a secret, lest you be the victim of a hate crime. If you’re taught to feel ashamed for who you are, you may not be inclined to talk to other people. A library is one place where you might find the books that can talk to you, and to help you know that you’re not alone.

Teen-agers of all types (different genders, sexualities, nationalities, ethnicities, body types, religions, etc.) need access to books that help them make sense of what they are going through. Denying them access to these books contributes to their marginalization and puts them at greater risk.

Why do some parents want to deny young readers access? I say “parents” because, according to the American Library Association, over half (55%!) of all challenges to books come from parents. To put that in perspective, the next-highest group of challengers are patrons (13%), followed by other (11%), administrators (9%), and board members (3%). I have to believe that, in seeking to deny readers access, these parents are acting in what (they think) is the best interests of their community. And, certainly, the desire to protect one’s children is universal (or nearly universal) among parents – and for good reason.

But any individual young person will not match one parent’s idea of what teenage-hood (or childhood) “is” or “should be.” There are as many different kinds of teen-agers (and children) as there are different kinds of adults. Never do we hear an adult say, “This book is inappropriate for adults” or “adults will like this.” Yet, if we replace the word “adults” with “teen-agers” or “children,” then we’ll see a phrase encountered far too often. A grown-up resists generalizations about him- or her-self, but is often quite happy to generalize about younger people. This (well-intentioned) impulse to protect young adults by upholding such generalized, abstract notions of “teen-ager” or “child” not only fails to prepare young persons for the sometimes cruel world they face, but in fact has a greater potential to make their lives harder.

I know that literature is not in itself a solution to the problems of homophobia and bullying. But it can help diminish the effects of both. And for the friends and families of Tyler Clementi, Seth Walsh, Asher Brown, Billy Lucas and all the other young GLBTQ people out there, we need to support the freedom to read.

Pingback: Jumping on the Banned Wagon « Write Up My Life

Pingback: News of the week | CMIS Evaluation Fiction Focus

Pingback: Jumping on the Banned Wagon | JulieHedlund.com