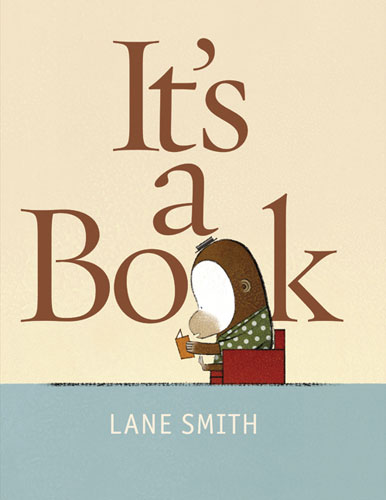

I’m surprised by the extent of the kerfuffle over the use of a single word in Lane Smith’s It’s a Book. In her Amazon.com review, librarian Margaret Burke writes, “I usually love Lane Smith’s books but was disappointed with the word jackass in the first page. I will NOT put this book in my library collection.” On her blog, Library Lady writes that the word “simply isn’t necessary” and that, although she “will still share the book in storytime,” she “just won’t read the last page.” Even Adam Gopnik’s smart and otherwise laudatory review in the New York Times takes issue with the word, calling it a “false note” and a “too-easy joke.”

I’m surprised by the extent of the kerfuffle over the use of a single word in Lane Smith’s It’s a Book. In her Amazon.com review, librarian Margaret Burke writes, “I usually love Lane Smith’s books but was disappointed with the word jackass in the first page. I will NOT put this book in my library collection.” On her blog, Library Lady writes that the word “simply isn’t necessary” and that, although she “will still share the book in storytime,” she “just won’t read the last page.” Even Adam Gopnik’s smart and otherwise laudatory review in the New York Times takes issue with the word, calling it a “false note” and a “too-easy joke.”

It is a joke, but easy? I defy Mr. Gopnik and anyone else to come up with a better punch line. “It’s a book, silly” and “It’s a book, donkey” simply are not as funny as “It’s a joke, jackass.” The double meaning of the word “jackass” makes the joke work. The character is both a male donkey and a foolish individual. No other punch line will work as well here.

The joke is not exclusively “for adults,” as many Amazon.com reviewers allege. It’s a joke for kids, too. How do I know this? I know this because kids will get the joke. A joke for adults goes over the heads of children – so, for example, the humor of a joke that relies upon sexual innuendo would likely be lost on a 7-year-old. But the “jackass” joke is one that a grade-schooler can get. I suspect that what really upsets the book’s critics is the idea of a child laughing at this “jackass” joke. Laughter conveys the child’s knowledge that the term for an animal is also a term for a blockhead. Laughter confirms that the child is not as “innocent” as the adult wishes to believe. Not willing to concede that his or her assumptions about the imagined innocence of children may be flawed, the adult instead strikes back at the evidence – which, in this case, is It’s a Book.

One Amazon.com reviewer even calls the word an “expletive,” but it isn’t. “Jackass” is a noun, and certainly an insult to the character at whom it’s directed, but I wouldn’t elevate it to the status of “expletive.” Nor would any reputable dictionary. Neither Webster’s Unabridged nor the Oxford English Dictionary lists “jackass” as “slang,” “vulgar,” “offensive,” or “taboo word” (these latter two are terms used by the OED to describe some expletives). It’s simply conveying the fact that this character is a bit of a dolt. And it’s making a joke as it does so.

Contemporary children face many serious problems: cuts in funding to education, overcrowded schools, poverty, bigotry, abuse, neglect, and so on. The word “jackass” doesn’t even make the list. I suppose one reason for opposing the word is that, unlike the many real problems faced by young people, this one seems more manageable. It’s a single word, it’s uncomplicated, and standing up against it plays upon our culture’s Romantic (and still popular) ideas of children – that they’re innocent, more “pure” than adults. For some critics, I expect, taking a “principled” stand against “bad language” is satisfying on many levels – emotional, moral, paternal/maternal, etc.

However, decrying the use of this word is also extremely silly. “Jackass” is a male donkey. “Jackass” is a fool. And, in the case of It’s a Book, “jackass” is a joke.

Jeff Pettiross

Jonathan Rogers

Gregory K.

Philip Nel

Jonathan Rogers

Gregory K.

Philip Nel

Gregory K.

Pingback: Links of the week | CMIS Evaluation Fiction Focus

Ms. Yingling

T. Crockett