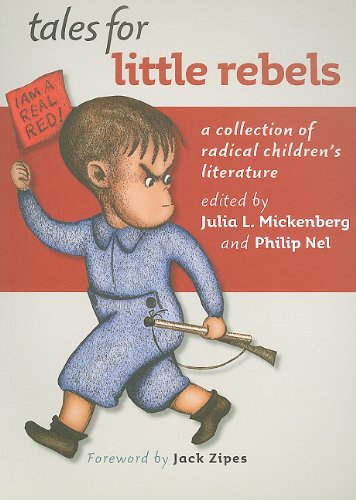

The headline reads “Occupying children’s minds: ‘Radical children’s literature at Wall Street protests.'”  Featured prominently is Julia Mickenberg’s and my Tales for Little Rebels.  After reading the piece (though, not, I suspect, the book itself), one commenter, writing under the name of “forcerecon2,” worrries that Tales for Little Rebels represents “the indoctrination of our children.”  Coming from the left but also opposing indoctrination, Occupy Wall Street organizer Kelley Wolcott writes in response to the suggestion that children of OWS protesters read Tales for Little Rebels: “I think that we should provide teaching related services that DO NOT have an agenda, and treat children in a respectful way that allows them to explore their own ideas about what is fair or not fair without imposing an adult agenda.”  Though the stories contained in the book are more sympathetic to Wolcott’s point of view than to forcerecon2’s, both statements convey only a partial understand how literature works.

The headline reads “Occupying children’s minds: ‘Radical children’s literature at Wall Street protests.'”  Featured prominently is Julia Mickenberg’s and my Tales for Little Rebels.  After reading the piece (though, not, I suspect, the book itself), one commenter, writing under the name of “forcerecon2,” worrries that Tales for Little Rebels represents “the indoctrination of our children.”  Coming from the left but also opposing indoctrination, Occupy Wall Street organizer Kelley Wolcott writes in response to the suggestion that children of OWS protesters read Tales for Little Rebels: “I think that we should provide teaching related services that DO NOT have an agenda, and treat children in a respectful way that allows them to explore their own ideas about what is fair or not fair without imposing an adult agenda.”  Though the stories contained in the book are more sympathetic to Wolcott’s point of view than to forcerecon2’s, both statements convey only a partial understand how literature works.

All children’s literature is political – from Dr. Seuss to The Poky Little Puppy to Left Behind: The Kids.   All stories bear the influence of the world in which they were produced; some display that influence more prominently, and others more successfully mask ideological assumptions.  There are no stories “that DO NOT have an agenda.”  Yet, if children’s literature serves a socializing function, predicting its effectiveness on children is a tricky business.  Child readers might embrace the message, or resist it, or … even forget all about it.

It’s true that Tales for Little Rebels does include some stories written by people who wished young readers to adopt a very specific, often quite sectarian, view of the world.  Caroline Nelson’s “Nature Talks on Economics” – one of the stories that inspired the coverage on The Daily Caller and Fox Nation – does harbor such aspirations.  In that tale, revolutionary chick cries, “Strike down the wall!” and liberates itself from the “egg state.”  A lesson about nature becomes a metaphor for revolution.

However, in and of itself, this story provides little evidence that Tales for Little Rebels is a tool of indoctrination.  First, it’s but one of 44 stories on subjects ranging from peace to the dignity of work, from the power of the imagination to opposing bigotry, from environmental protection to finding strength in organizing – stories that would be quite apropos to the OWS protesters, incidentally.  It would be truly remarkable for one story to manage to indoctrinate those who read it.  Taken in context with other literature or read in a socialist family (as “Nature Talks on Economics” very likely was done, originally), it stands a stronger chance – but only if the child hearing the story identified with the values of his or her parents.

Which brings me to my second point: children are not passive beings, empty receptacles which people can fill with ideas.  They’re certainly affected by the culture in which they live, but they’re also capable of thinking for themselves.  Indeed, we hope that some of the stories in Tales for Little Rebels nurture that kind of critical thinking – Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish’s The Races of Mankind, which uses science to challenge racism, or Oscar the Ostrich, in which the birds defeat a would-be fascist by taking their heads out of the sand, and speaking out against him.  Though, of course, children may fail to get these messages.  Tales for Little Rebels includes a scene from Revolt of the Beavers, a play in which beavers liberate Beaverland from a tyrant, and redistribute the wealth.  When an NYU Professor of Psychology interviewed hundreds of child audience members about lessons the play imparted, they told him they learned things like “never to be selfish,” and “beavers have manners just like children.”  Not exactly what (I imagine) the play intended to teach.

That brings me to my third point – a point which I’m going to borrow from Philip Pullman, since he’s far more articulate than I am. Â Just because an author intends for readers to receive a certain message from a work, there’s no guarantee that the story will turn out as the author intends:

whatever my intention might have been when I wrote the book, the meaning doesn’t consist only of my intention. The meaning is what emerges from the interaction between the words I put on the page and the readers’ own minds as they read them. If they’re puzzled, the best thing to do is talk about the book with someone else who’s read it, and let meanings emerge from the conversation, democratically.1

And that’s the best message to take away from this conversation – and it’s what I think Wolcott means when she encourages “Treating children with respect and allowing them to explore their own ideas.”

Tales for Little Rebels contains a range of opinions from people on the twentieth-century left.  Though Julia and I expected that most of the stories would resonate with contemporary progressives, we also deliberately included some stories that would not (notably “ABC for Martin,” which we nicknamed “the Communist ABC”).  We didn’t want to whitewash history by excising stories that may be embarrassing to those on the left – so, those stories are in the book, too.  But they’re in there along with introductory material that invites readers to think critically about them.  We didn’t create the book hoping that it would encourage everyone to adopt a particular “party line.”  Rather, we hoped that it would encourage readers of all ages to think, to ask questions, and to understand that the world in which they live is not a given.  People can change it.  They can change it.

_____________________

1. Philip Pullman, “Intention,” Keywords for Children’s Literature, ed. Philip Nel and Lissa Paul (New York University Press, 2011).

Related content (updated 19 Nov. 2011):

- Radical Children’s Literature Now! (article) (12 Nov. 2011)

- Radical Children’s Literature Now! (video) (30 July 2011)

- Radical Children’s Literature Now! (handout) (25 Jun. 2011). This also includes relevant awards and other resources.

Ira Mickenberg

Pingback: From the Square :: NYU Press » ‘Scary’ little rebels, or rebels with a cause?

Yvette Mickenberg

Marah

Philip Nel

Pingback: Trouble, Butler and OWS | (Making / Being in / Staying in) TROUBLE

Pingback: Fusenews: “Even books meant to put kids to sleep should give them strange dreams.” « A Fuse #8 Production

Pingback: American Studies and Occupy Wall Street « AMS :: ATX

Marah

John Swanson