A brief report on the 2013 International Research Society for Children’s Literature (IRSCL) conference (held this year in Maastricht), including: Dutch children’s literature, street signs, and a loss of confidence in cut flowers.

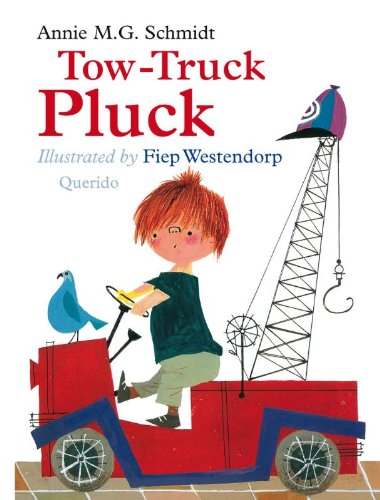

Tow-Truck Pluck and other tales by Annie M.G. Schmidt

I first read of Annie M. G. Schmidt in Guus Kuijer’s masterpiece, The Book of Everything (if you haven’t read this book, go read it now). Thanks to Kuijer, I bought Pink Lemonade, a collection of her poems. In a bookshop in Amsterdam earlier this month, after picking up her Jip and Janneke (1963), I was talking to a clerk about Dutch children’s literature.  He said yes, Dutch children all know Jip and Janneke, but everyone grew up reading Schmidt’s Tow-Truck Pluck (1971). That’s the one I should get, he said.  So, I bought both books, and have been thoroughly enjoying Tow-Truck Pluck. It’s charming, whimsical, and wise.  Reminds me a bit of Astrid Lindgren, actually.  During the IRSCL, I and some friends also attended the film adaptation (2001) of her book Minoes (1970), the story of a cat who turns into a young lady and assists a shy reporter. More English-speaking readers should get acquainted with Schmidt’s work.  (Bonus: she translated Harold and the Purple Crayon into Dutch – Paultje en het paarse krijtje.)

I first read of Annie M. G. Schmidt in Guus Kuijer’s masterpiece, The Book of Everything (if you haven’t read this book, go read it now). Thanks to Kuijer, I bought Pink Lemonade, a collection of her poems. In a bookshop in Amsterdam earlier this month, after picking up her Jip and Janneke (1963), I was talking to a clerk about Dutch children’s literature.  He said yes, Dutch children all know Jip and Janneke, but everyone grew up reading Schmidt’s Tow-Truck Pluck (1971). That’s the one I should get, he said.  So, I bought both books, and have been thoroughly enjoying Tow-Truck Pluck. It’s charming, whimsical, and wise.  Reminds me a bit of Astrid Lindgren, actually.  During the IRSCL, I and some friends also attended the film adaptation (2001) of her book Minoes (1970), the story of a cat who turns into a young lady and assists a shy reporter. More English-speaking readers should get acquainted with Schmidt’s work.  (Bonus: she translated Harold and the Purple Crayon into Dutch – Paultje en het paarse krijtje.)

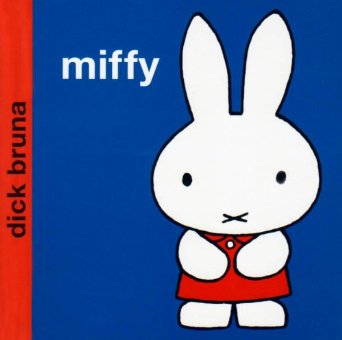

Miffy!

Miffy!

I think more English-speakers know Dick Bruna’s Miffy books, or at least are familiar with his iconic character.  (My general sense is that she’s better known in the UK than in the US or Canada.) But she’s such a phenomenon in the Netherlands that there’s an entire store devoted to Miffy and other Dick Bruna paraphernalia.  Here is a photo from inside the Miffy store in Maastricht:

Anne Frank

The most famous Dutch child is actually German. As I learned at the Anne Frank House, Otto Frank moved his family from Frankfurt to Amsterdam in order to escape Nazi persecution. (Before Maastricht, I spent a few days wandering Amsterdam and visiting my cousin.) If you are ever in Amsterdam, definitely visit the Anne Frank House. I had to wait a little over an hour in line, but it was well worth it. The museum is very well-organized, and contains lots of illuminating artifacts – including videos, photos, and the diary itself. It’s actually in the building where she and her family hid until they were betrayed to the Nazis. You can climb the stairs to where the family lived while in hiding. I was most struck by something Otto Frank – the sole survivor of the two families who lived two years in the Annex – said, on one of the videos. He said that the Anne Frank he encountered in the diaries was not the daughter he knew. The diaries revealed a side of her that he never saw. From this, he concluded that no parents ever truly know their children.

The most famous Dutch child is actually German. As I learned at the Anne Frank House, Otto Frank moved his family from Frankfurt to Amsterdam in order to escape Nazi persecution. (Before Maastricht, I spent a few days wandering Amsterdam and visiting my cousin.) If you are ever in Amsterdam, definitely visit the Anne Frank House. I had to wait a little over an hour in line, but it was well worth it. The museum is very well-organized, and contains lots of illuminating artifacts – including videos, photos, and the diary itself. It’s actually in the building where she and her family hid until they were betrayed to the Nazis. You can climb the stairs to where the family lived while in hiding. I was most struck by something Otto Frank – the sole survivor of the two families who lived two years in the Annex – said, on one of the videos. He said that the Anne Frank he encountered in the diaries was not the daughter he knew. The diaries revealed a side of her that he never saw. From this, he concluded that no parents ever truly know their children.

Bart Moeyaert

“All of us are composed of compost. Â And all of us are capable of sewing seeds of happiness.”

– Bart Moeyaert

As I mentioned, I was in Maastricht for the IRSCL (Aug. 10-14), and while it would be impossible to offer a full account of that conference (there were about 9 concurrent sessions), here are a few highlights. Â Bart Moeyaert‘s dinner speech on Sunday was magnificent. Â He began by greeting us, “Good evening ladies and 11 gentlemen.” Â (There are far more women who study children’s literature than men, and IRSCL attendance reflected that.) Â Then, he started his speech with the sentence “Recently I lost confidence in cut flowers.” What followed was a wise, witty, beautiful speech about hope, happiness, and, yes, cut flowers.

The way he spoke reminded me of Guus Kuijer’s Book of Everything – which, as I say, is a favorite (and seems to be the sole Kuijer book in English).  So, I now want to read Moeyaert’s books, about five of which have been translated into English.  I have just placed an order for his Dani Bennoni: Long May He Live (2004) and It’s Love We Don’t Understand (1999).

Keywords for Children’s Literature, International Edition

“Imagine a conference on Literature.”

– Emer O’Sullivan

Until IRSCL, I’d not even heard of Bart Moeyaert, despite the fact that he is an award-winning novelist and poet. Â This is why I went to his talk and why I attend IRSCL in the first place: I want to learn more about the vast world of children’s literature. As Emer O’Sullivan observed, “There are very few conferences so international [as IRSCL]. Imagine a conference on Literature.” Â And she’s right. That’s what makes the field so unmanageable and so interesting.

She made that comment during our roundtable, “Towards an International Version of Keywords for Children’s Literature,” which featured (from left to right, below), me (co-chair), Emer O’Sullivan, Nina Alonso, Nina Christensen, and Lissa Paul (co-chair).  (Photo by Sarah Park Dahlen).

If Keywords for Children’s Literature (NYU P, 2011) does well enough commercially, Lissa and I will edit a second edition that adds missing keywords and missing perspectives.  The original book’s contributors are from the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand; one editor (me) is American, and the other (Lissa) Canadian.  So, it’s very focused on children’s literature in English (as its introduction acknowledges). At a Nordic Children’s Literature Conference in Oslo last August, attendees asked us: Where’s the Nordic Literature?  And we thought: Right. Good point. So, thanks to Nina Christensen and the encouragement of Mavis Reimer (both of whom were at the conference), we convened this panel, during which we both gained many valuable suggestions on how we might proceed, and learned how challenging such a task would be.  Should one “internationalize” an extant entry by simply weaving in references to texts from non-Anglo countries?  If so, then which texts?  And what about keywords that emerge out of a particular linguistic or cultural context?  We need more contributors from different countries, and (we think) an editor from a non-English speaking country.  Should we get the opportunity, creating a more international edition will be a daunting task, but one very much worth pursuing.

A specialist in empathy

We go to conferences to learn from other people. Here are a few of the good ideas I heard.

We go to conferences to learn from other people. Here are a few of the good ideas I heard.

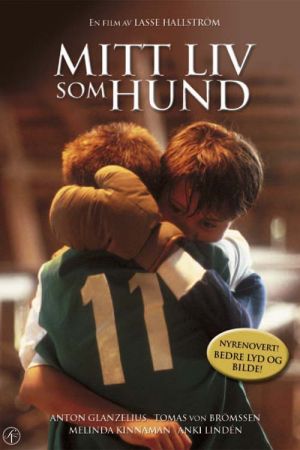

I keep coming back to the line, “I am a specialist in empathy,” from Ingemar, the 13-year-old narrator of Reidar Jönsson’s novel My Life as a Dog. Ingemar says, “I also keep track of other peoples’ accidents. Not only my own. One must compare. In reality, I am a specialist in empathy.”  I’m as intrigued by the notion (how would one become a specialist in empathy?) as I was by the paper in which it appeared: Nina Christensen’s analysis of three iterations of Laika in children’s culture.  (The other two were Lilian Brøgger’s picture book Nina Sardina, and the short film The Little Dog Laika).

The disabled thing

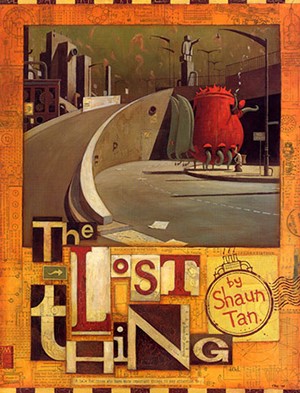

Nicole Markotic interpreted the title character of Shaun Tan’s The Lost Thing as a metaphor for disability. It’s out of place in other ways than just being lost – its non-normative body also marks it as different in this society. Â I’d never thought about that, nor that the boy himself’s anti-social behavior and obsessive collecting also aligns him (metaphorically) with an autistic child.

Nicole Markotic interpreted the title character of Shaun Tan’s The Lost Thing as a metaphor for disability. It’s out of place in other ways than just being lost – its non-normative body also marks it as different in this society. Â I’d never thought about that, nor that the boy himself’s anti-social behavior and obsessive collecting also aligns him (metaphorically) with an autistic child.

Against empathy

Lydia Kokkola‘s “Limiting Empathy: Refusing to Care About Literary Characters” taught me about affect and its limits in literary criticism. Â I especially liked her willingness to interrogate assumptions she had thought to be true. Â She had wanted to believe that empathizing with a character, feeling her trauma, would help us grow in understanding. But she’s changed her mind. Â I can’t do her argument justice, but her bibliography (incomplete, compiled from my notes) forms a great reading list for anyone interested in affect.

- Kenneth B. Kidd, “‘A’ is for Auschwitz: Psychoanalysis, Trauma Theory, and the ‘Children’s Literature of Atrocity'” Children’s Literature 23 (2005): 120-149. I’ve read this one, and recommend it.

- Eric Tribunella, Melancholia and Maturation: The Use of Trauma in American Children’s Literature (2009). I also recommend this one.

- Simon Baron-Cohen, Zero Degrees of Empathy (2012). Haven’t read this.

- Martha Nussbaum, Upheavals of Thought (2001). I’ve read about 100 pages of this one. Very interesting.

Martha Nussbaum, Cultivating Humanity (1997). Haven’t read this.

Martha Nussbaum, Cultivating Humanity (1997). Haven’t read this.- Blakey Vermeule, Why Do We Care About Literary Characters? (2011). Haven’t read this one either.

- Suzanne Keen, Empathy and the Novel (2010). Lydia Kokkola thinks this and Vermeule are better than Nussbaum, which catches my attention because Nussbaum’s work is smart. (I haven’t read this one.)

- Anastasia Ulanowicz, Second-Generation Memory and Contemporary Children’s Literature: Ghost Images (2013). Â I edited this one! Â While that was a pleasant recognition for me, all credit goes to Anastasia. The ideas are all hers.

What does it mean to love and act morally?

Deb Dudek‘s “‘Caring Gets You Dead, huh?’ or ‘all their wonderful nakedness’: Love and Moral Action in the Vampire Diaries” caught me immediately with a great hook of an opening line: “Don’t you just hate it when two beautiful men are in love with you?” But its central question (about the relationship between love and moral action) is what kept me thinking. The paper – which is part of a book project on Buffy, Twilight, and (obviously) The Vampire Diaries – ended with a close-reading of Moby’s cover of New Order’s “Temptation.”  If you haven’t heard that cover, you really need to, and so I’m embedding it below.

Due to scheduling conflicts, I missed so much, including Naomi Hamer‘s reading of the Harold and the Purple Crayon app, Libby Gruner on “Misreading the ‘Classics’: Dorks, Wallflowers, and The Catcher in the Rye,” Erica Hateley on Shaun Tan’s The Lost Thing (film and book both), and many others!  (Too many to list here.)

It says, “This book is worth reading”

Robin Bernstein won the IRSCL book award for Racial Innocence, which is the fifth (or sixth? or more-th?) award that book has won, and rightly so.  She recorded a speech to be played at IRSCL, but… the sound failed.  So, here’s what everyone should have heard.

Walk – Don’t Walk

Challenging the de facto masculine figures that appear in your typical traffic signs, here is one spotted in Maastricht.

|

Half of myself

My favorite part of this conference – and of conferences in general, these days – is people. Â I like to learn (as the preceding indicates), but I love seeing friends and making new friends. A note to younger readers who may have read that it’s nigh impossible to make good friends once you’re over 30: don’t believe it. Â You can still make good friends in your 30s and 40s (and, I’ll wager, after that!).

Though I have very good friends I met in my late ‘teens / early 20s (and before then), I think that more of the people to whom I am close I have met more recently. This is partly because I’ve moved or because people change. But it’s more because I now understand more acutely that friends are all we have. It’s not that I took friendships for granted when I was younger. I was aware of their necessity and fragility then, too. It’s more that – well, I don’t know that I can articulate precisely why.  Friendships are vital, sustaining, impermanent, though (I think) I now have a stronger sense  of which ones are more likely to endure. I can’t think of anything profound on which to conclude this thought, so I’ll leave you with a quotation from Matteo Ricci’s On Friendship: One Hundred Maxims for a Chinese Prince:

My friend is not an other, but half of myself, and thus a second me – I must therefore regard my friend as myself.

This is not a table

And finally, we bring you:

(a) Making an ironic point, a sign uses a table in order to advise others not to use it.

(b) An unlikely alliance between table and sign, in which latter defends former.

(c) A firm refutation of the table’s table-ness: if the sign is using that flat surface, then that flat surface cannot be a table.

(d) A table having an identity crisis. And a sign mocking it.

(e) All of the above.

(f) None of the above.

Zoe

Philip Nel