As you likely already know, Margaret Mary Vojtko – an adjunct professor of French for 25 years – was found dead on her front lawn on September 1st. Facing mounting medical bills and lacking money to maintain or even heat her house, she died of a heart attack earlier that day. As Daniel Kovalik writes, “Even during the best of times, when she was teaching three classes a semester and two during the summer, she was not even clearing $25,000 a year, and she received absolutely no health care benefits.” His article, “Death of an adjunct,” has been widely shared across social media, been reprinted in the Huffington Post, and inspired stories in Inside Higher Ed, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and Gawker.

In some senses, her death was not preventable: she was 83 and fighting cancer. It’s likely that she would have died sooner rather than later.

But in other senses, her job killed her. And I’m not speaking figuratively. As Mr. Kovalik notes,

in the past year, her teaching load had been reduced by the university to one class a semester, which meant she was making well below $10,000 a year. With huge out-of-pocket bills from UPMC Mercy for her cancer treatment, Margaret Mary was left in abject penury. She could no longer keep her electricity on in her home, which became uninhabitable during the winter. She therefore took to working at an Eat’n Park at night and then trying to catch some sleep during the day at her office at Duquesne. When this was discovered by the university, the police were called in to eject her from her office. Still, despite her cancer and her poverty, she never missed a day of class.

Her job left her unable to meet her basic needs (heat, food, medicine). Furthermore, that level of stress has an adverse effect on a person’s health. People forced to cope with large levels of extreme stress –Â and poverty is definitely an extreme stress – have shorter life expectancies. A job that reduces you to poverty also hastens your demise.

I would not suggest that Duquesne University acted alone in killing Professor Vojtko, nor that all individuals at the university lacked sympathy for her. But the university is certainly an accomplice. While it claims to be a Catholic university, Duquesne has fought its adjuncts’ attempts to unionize, alleging that it deserved an exception on religious grounds; in contrast, Georgetown University, citing the Catholic church’s commitment to social justice, recognized its adjuncts’ union.

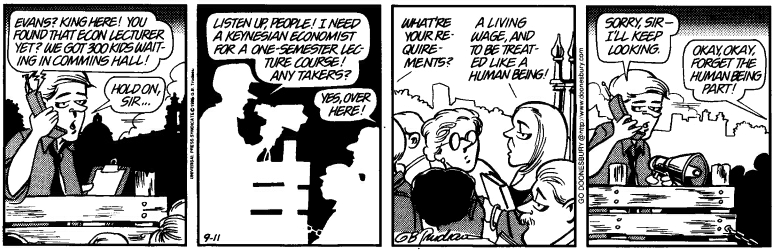

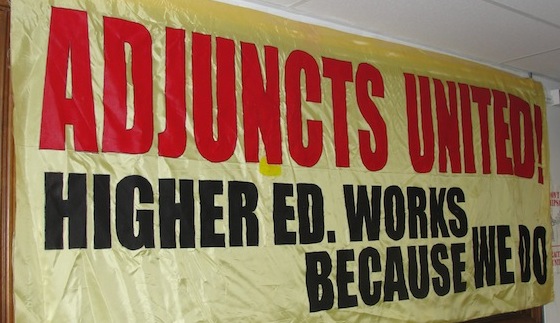

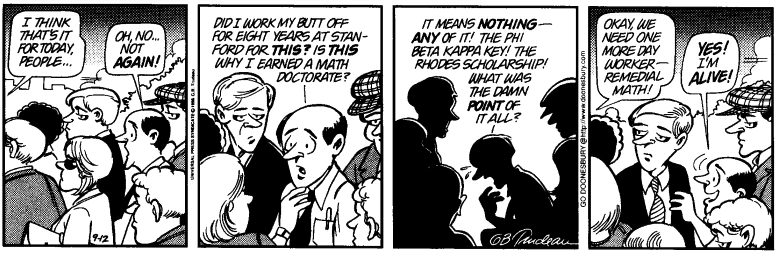

Duquesne has many accomplices. Its treatment of Professor Vojtko was cruel, but not unusual. Exploitation of adjunct labor has become the norm in academe. Faced with rising costs (and, in “state” schools, decreasing support from the state), colleges and universities consider adjuncts an “economic” solution to their staffing needs. They’re highly qualified cheap labor, and – as the number of tenure-track jobs decreases – there are more Ph.Ds. to choose from each year. It’s a buyer’s market. Duquesne only did what other universities and colleges have done. Indeed, at American universities, 73% of all instructors are non tenure-track (adjuncts or grad students).*

Yes, some institutions treat adjuncts more humanely than others. Some provide health insurance and even retirement plans. Some. But, even under the best conditions, adjuncts are second-class citizens. And, yes, some make it on to the tenure track. But most do not.

Relying on adjuncts as the primary way to teach classes has become normal, but it’s not good for the adjuncts and it’s not good for higher education. Adjuncts owe no loyalty to the institution that employs them; so, at the beginning of term, heads of departments must scramble to find people to cover classes. That’s no way to run a university. As Professor Vojtko’s death makes all too clear, that’s also not a humane way to treat an educator –Â or anyone, for that matter.

One reason that universities rely upon adjunct labor points to the third group responsible for killing Professor Vojtko: all those who mock academic labor, consider teaching a cushy job, argue that educators are lazy (as in the familiar misconception, you only teach a few classes and then you get summers off!). The concerted effort to refashion intellectual labor as a form of leisure diminishes sympathy for a hard-working group that has much to contribute. It deprives them of their humanity. It makes them easy targets. They become easy to neglect, easy to ignore, and easy to crush beneath the weight of indifference and poverty.

Certainly, teachers –Â at primary, secondary, and post-secondary levels –Â are not the only people who have been maligned in this way. Factory workers (especially unionized ones), policemen, firemen, all public-sector workers have all been criticized as somehow unworthy of the salary and benefits they receive.

I’ve been using the passive voice, failing to name just who is doing the maligning, because this is not merely the fault of one particular faction. Certainly, responsibility lies with pundits on the right who complain about “the takers” mooching off “the makers,” governors who slash education budgets while simultaneously giving tax breaks to the wealthy, and businesses pushing an “educational reform” because it serves their financial interests. But people on the left are also at fault. In an effort to reduce the cost of college (certainly a laudable goal), President Obama fails to address the single greatest contributing factor to the rising cost of tuition: decreasing state support requires universities to find money from other sources. This is not something that the privately funded Duquesne University (Professor Vojtko’s employer) faces, but the president’s move to hold colleges accountable without a comparable push to restore public funding simply perpetuates the myth that educators are too highly paid. This myth obscures the fact that many of us are not well paid at all.

I spent three years as an adjunct. Those years (1997-2000) were not happy ones. I was often angry. Indeed, I am frankly surprised and grateful that I have friends from that period of my life: a bitter person isn’t fun to be around. Today, I am tenured, a full professor of English at Kansas State University (which receives 20% of its funding from the state). As an ex-adjunct, I find stories like Professor Vojtko’s especially troubling. Her path might have been my path. It wasn’t, but it has been and will be the path of many others. The exploitation of adjuncts has only increased since my days as an adjunct.

This brings me to the fourth and final group I would indict in the death of Professor Vojtko: me, and people like me. No, I did not create the conditions that foster the exploitation of adjuncts. Nor do I support those who think that college should be run like a business, and am frankly appalled by the efforts (by President Obama, and others) to apply a capitalist ethos to institutions that strive to serve the public good. And, sure, I’m sympathetic to adjuncts. But that’s not enough.

Those of us who have attained even a modest amount of institutional power need to speak up. We need to support organizations fighting for adjunct rights –Â such as the American Association of University Professors. I have been intending to join this group for years, and only now –Â while writing this paragraph –Â did I actually join. Writing this essay and joining that group aren’t sufficient, I know. But it is at least a step in the right direction.

Those of us who have attained even a modest amount of institutional power need to speak up. We need to support organizations fighting for adjunct rights –Â such as the American Association of University Professors. I have been intending to join this group for years, and only now –Â while writing this paragraph –Â did I actually join. Writing this essay and joining that group aren’t sufficient, I know. But it is at least a step in the right direction.

We need to stop exploiting adjuncts. It’s killing them. And it isn’t good for the rest of us, either.

__________

* Note and Correction (added 22 Sept. 2013, 5:40 pm): According to the study, the 73% includes full-time, non-tenure track faculty (15%), part-time/adjunct faculty (37%), and graduate employees (21%). Those first two groups are both adjunct: that is, “full-time, non-tenure track faculty” is the equivalent of adjunct. So, if we add these two together, then we get 52% adjunct, plus an additional 21% graduate students, for a total of 73%. A more recent study indicates that  non-tenure track faculty (adjuncts and graduate students) now comprise 76% of instructors at American colleges and universities.  The correction here is that my original post stated that “73% of all instructors are now adjuncts”; using the source I originally cited, the more precise way to state this is that “73% of all instructors are now non-tenure track (adjuncts and graduate students).”  So, when Chris pointed this out (comment no. 37, below), I made the change.

Resources (updated 18 Nov. 2013, 3:00 pm)

- How much do adjuncts make? Check out The Adjunct Project.

- Adjunct Nation

- American Association of University Professors

- New Faculty Majority

- Justice for Adjuncts, Rather Than Charity. Â A Change.org petition (launched 22 Sept.), asking Duquesne to grant adjuncts union representation, job security, a living wage, and health and retirement benefits.

- MLA Subconference. Chicago. January 8-9, 2014. Â “an autonomous meeting of graduate workers, adjunct and contingent faculty, and unemployed or independent intellectuals that will coincide with the 2014 MLA convention.”

- Daniel Kovalik, “Death of an adjunct.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 18 Sept. 2013.  This is the article that started all the recent discussion.

- L. V. Anderson, “Death of a Professor.” Slate, 17 Nov. 2013. A nuanced look at Margaret Mary Vojtko, her death, and “the devil’s bargain universities have made by exploiting adjuncts.”

- Brian Croxall, “The Absent Presence: Today’s Faculty.” Brian Croxall 27 Dec. 2009.

- James J. Donahue, “In a sense, I am Jacob Horner.” Creativity in the College Classroom, 20 Sept. 2013.  Great rebuttal to Duquesne’s claims that its own limited acts of charity somehow compensate for 25 years of exploitation.

- Joe Fruscione, “Adjunct, Help Thyself.” Vitae 14 Oct. 2013.

- Terry McGlynn, “On being a tenure-track parasite of adjunct faculty.” Small Pond Science 24 Sept. 2013.

- Christian Pyle, “Adjuncts: the invisible majority.” North of Center, 27 Apr. 2011. An adjunct explains … the life of an adjunct. This will be especially useful to any readers beyond academe or in academe but from different countries. Thanks to Kate Bowles (@KateMfD) on Twitter, I can tell Australian readers that “US adjunct is closest to Australia’s sessional/casual precariat. #highered‘s friends without benefits.”

- Roger Whitson, “How to Survive a Graduate Career.” Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor 22 (2013): 58-70.

- The #iammargaretmary hashtag on Twitter

- “25 Telling Facts About Adjunct Faculty Today,” Best Colleges Online, 17 Sept. 2012.

Tosha Sampson-Choma

Philip Nel

Frances Cachon

Charles Hatfield

Christian Pyle

Charles Petterson

Philip Nel

Philip Nel

Liz Evans

Erin Wilson

Brigitte Fielder

Gwen Tarbox

Tim Schneider

Mary

Janet blackman

dreamingchange

Lisa

Victoria Brockmeier

Maria Maisto

Philip Nel

Pingback: This Job Can Kill You. Literally. | Research Material

Vanessa Vaile

Julia Eichelberger

K. Mushtaq Elahi

Barbara

Tim Warneka

Michael Marsh

Pingback: This Job Can Kill You. Literally. | Habari Gani, America!

Alyssa

Philip Nel

Vincentius Patricius

Aaron

Kate

Joanna

Carlota

Pingback: Sunday Salon: What I’ve Been Reading Online | the dirigible plum

Chris

Laura Winton

Jenna

JD

Philip Nel

Michael

Caroline McAlister

Ahli Anggur

Chris

Emma Watson

Alex. Arthur

Dawn

Pingback: Justice for Adjuncts | Lucubramus

Pam

John

John

MBG-ITH

Emma Watson

Emma Watson

Emma Watson

Vincentius Patricius

paul sheldon

paul

Vincentius Patricius

America Danvers

Maha Muslimah

Vincentius Patricius

Dennis Bathory-Kitsz

Chris

Vincentius Patricius

Dennis Bathory-Kitsz

Pingback: Education Reform: A Story About Me, Mexico and the US | The Fumi Chronicles

Vincentius Patricius

Pingback: New Grad Student Insights - Neil Traft

Pingback: Adjuncts, Ass-hats, and Adding to the Ether | Spilt Infinitive Digital Literary Magazine

Barry Roberts Greer

Frank BC

Pingback: Graduation: What Next? | Chera Hammons: Poet and Writer

Pingback: Adjuncts are Essential (1) | the Essential Adjunct

Pingback: You Might be an Adjunct | the Essential Adjunct