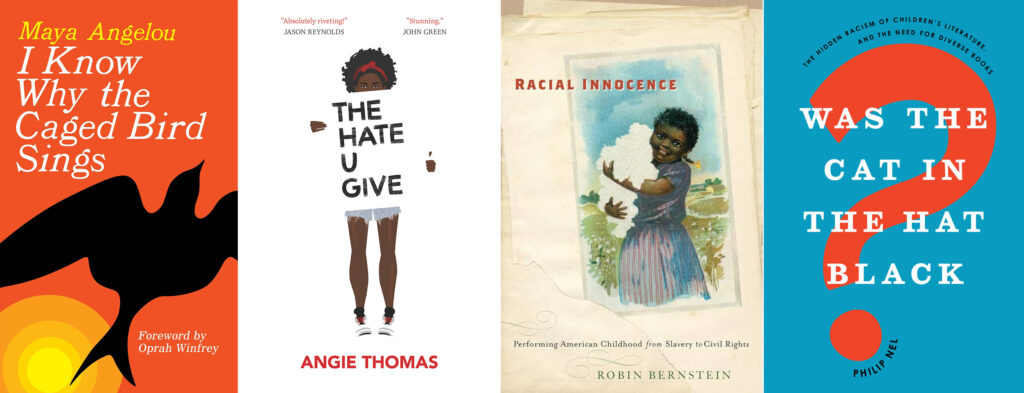

Back in April, US Defense Secretary Pete “Signal” Hegseth ordered 381 books removed from the US Naval Academy’s Nimitz Library. These included works read by young people—Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give—and scholarship on books for young people, such as Robin Bernstein’s Racial Innocence and my Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature and the Need for Diverse Books.

The editor of Bookbird, the journal of the International Board of Books for Young People, asked me to write about it. I did, and the piece — “Being Banned Is Not an Award” — came out last week.

Though I have written about censorship before, during the editing process, I gained a deeper understanding of how censorship can, in some circumstances, be strategic. And I have lately wondered if I should be more strategic.

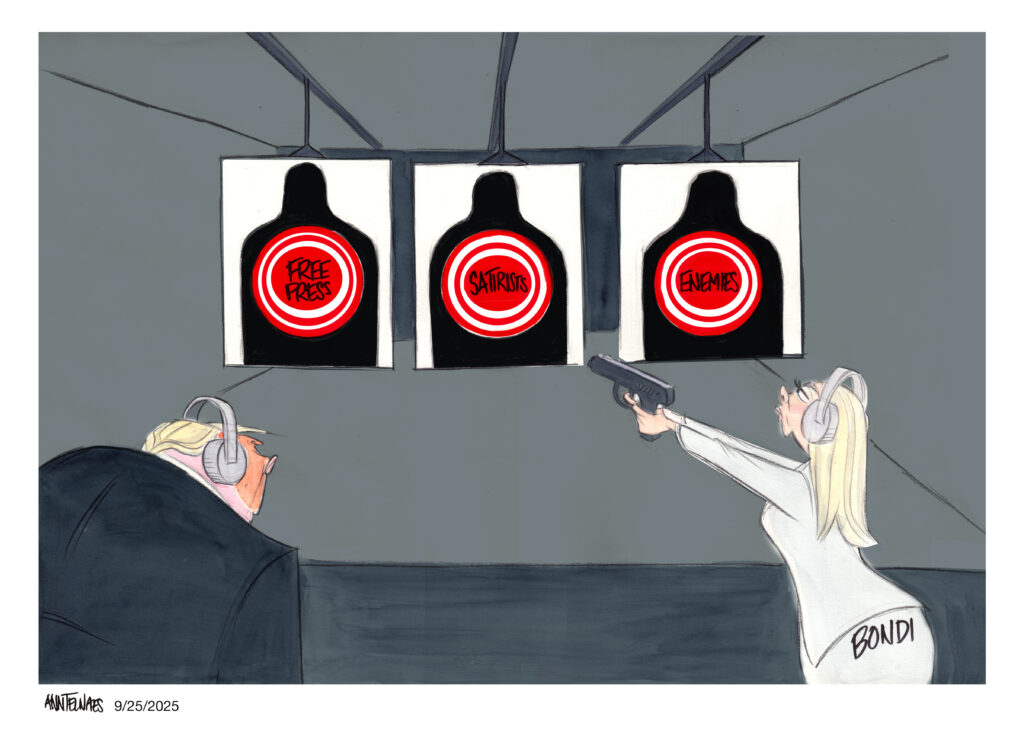

As we edited my piece, the editor worried that my comments about Pete Hegseth constituted libel. The editor also thought this sentence, from late in the piece, potentially libelous: “The Trump administration is rewriting all government websites to align with whatever lies it’s currently promoting.” However, as I told the editor, libel is a false statement that may damage a person’s reputation. My statements were true. Of course, America’s thin-skinned, whiny orange overlord considers all criticism to be libel. But I didn’t think we should use his fragile ego as a standard for determining “libel” or anything else.

The editor asked if I could make some changes, and suggested that I try to make the piece “‘timeless’ so that it could be read universally, regardless of time and place.” Though I made other changes, I said no, that I could not make it “timeless.” I could certainly aim for greater clarity, but I could not strive for timelessness. The piece addresses a current event — that fact itself immediately indicates its time and place.

The editor responded, apologizing for the ”timeless” advice, and explained “I grew up in a country where criticizing government (at that time) can lead to disappearance of the person, so people had to learn how to do it in a certain ways.” As he said, “There is a certain balance between being personal enough but also impersonal enough to protect themselves.”

I then understood that I was wrong. I had thought that I was facing editorial censorship on a piece about censorship. But the editor was proposing censorship as a strategy for speaking out safely amidst autocracy. He was trying to save me from myself.

Because I grew up in a country that taught me I had a right to freedom of speech (even if that right has always been imperfectly upheld), I decided not to follow his advice. After all, the laziest search of my published writings, my blog, my social media shows me to be a critic of the Trump regime — going back to at least 2016. The title of one of my pieces is “Trump Is a Liar. Tell Children the Truth.” So, I reasoned, it’s too late for me. If the regime decides that I fall into its zone of interest, there’s ample evidence of my anti-fascist writings for them to persecute me.

This month, I have had moments where I’ve wondered if I should have followed the editor’s advice. It’s less the attempt to silence Jimmy Kimmel, and more that it’s now apparently dangerous both to condemn all political violence and to acknowledge that, in the case of Mr. Kirk’s murder, the target of said violence was a professional bigot who encouraged violence for his own ends.

The late Mr. Kirk advocated “lethal force” against immigrants, said the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was “a huge mistake,” said that journalist Joy Reid, First Lady Michelle Obama, and Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson “do not have the brain processing power to be taken seriously” – and so they “had to go and take a white person’s job.” He called Democrats “maggots, vermin, and swine,” promoted lies about the 2020 election, called members of the LGBTQ+ community “freaks,” and claimed that Islamic areas were “a threat to America.” He alleged that Haitian immigrants were “raping your women and hunting you down at night.” He blamed anti-whiteness on the “Jewish donors” who, he claimed, funded it. He even said that “it’s worth it to have a cost of, unfortunately, some gun deaths every single year so that we can have the Second Amendment.”

Though his views ranged from false to dangerous, his murder was unequivocally bad. Whether the target is Speaker of the Minnesota House of Representatives Melissa Hortman or conservative activist Charlie Kirk, all political violence is bad.

But I do understand why all members of groups he disparaged might not mourn his death.

As for me, though I do not mourn what he stood for, I do mourn his death. To be shot is terrifying, and to be shot in public is even more so: no one should have to suffer that end. I also mourn for the man he could have become. I believe in people’s capacity to learn, and to change — if given the opportunity. He no longer has the opportunity to put his considerable talents to better use. I mourn that, too.

It should not be controversial to say these things. Just as it should not be controversial to quote Mr. Kirk’s words — those are his legacy.

Ta-Nehisi Coates provides some characteristically helpful context in this Atlantic essay:

More than a century and a half ago, this country ignored the explicit words of men who sought to raise an empire of slavery. It subsequently transformed those men into gallant knights who sought only to preserve their beloved Camelot. There was a fatigue, in certain quarters, with Reconstruction—which is to say, multiracial democracy—and a desire for reunion, to make America great again. Thus, in the late 19th century and much of the 20th, this country’s most storied intellectuals transfigured hate-mongers into heroes and ignored their words—just as, right now, some are ignoring Kirk’s.

As Coates points out, “Burying the truth of the Confederacy, rewriting its aims and ideas, and ignoring its animating words allowed for the terrorization of the Black population, the imposition of apartheid, and the destruction of democracy.” And, he concludes, “The import of this history has never been clearer than in this moment when the hard question must be asked: If you would look away from the words of Charlie Kirk, from what else would you look away?”

Though publicly speaking the truth has become more dangerous in the US, we must not look away.

So, while I’ve had moments of wondering whether I made the right choice, they were but moments. I made the right editorial choice in June, and I think I am making the right choice today — even if it feels like a more dangerous moment now.

As Timothy Snyder reminds us, most of autocracy’s power is freely given. So, we must not surrender in advance.

The greatest risk we face today is not the suspension of a talk show. Nor is it being fired for speaking the truth.

The greatest risk we face today is allowing the authoritarians to take this country from us. The greatest danger is fascist USA for generations to come. It is far easier to fight fascism now, in a period of autocratic breakthrough, when the autocrats are merely trying to consolidate power and act with impunity. The fight is much harder once autocrats have already consolidated power.

So, I do not plan to silence myself. For as long as I can, I will speak up and speak out.