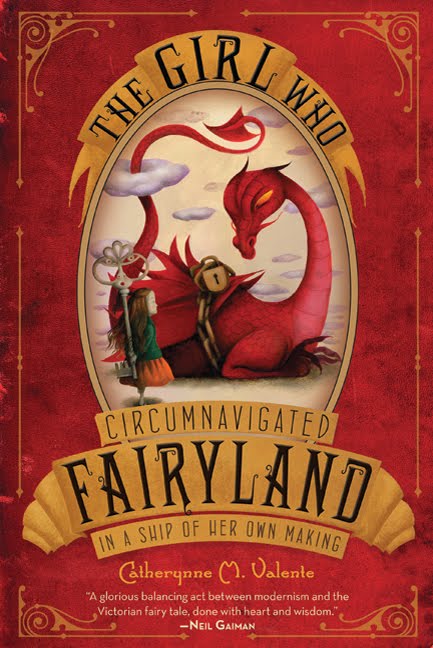

The problem with a blurb from Neil Gaiman on a cover is that, invoking Gaiman, it inevitably diminishes the book by comparison. This is not the book’s fault. Gaiman is one of our most gifted contemporary writers. Catherynne M. Valente may not be, but I wouldn’t even be thinking about the comparison if Gaiman’s endorsement were absent from the cover. Her The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making is clever, well-plotted, engaging, and inventive. It’s not Gaiman, but it is good.

The problem with a blurb from Neil Gaiman on a cover is that, invoking Gaiman, it inevitably diminishes the book by comparison. This is not the book’s fault. Gaiman is one of our most gifted contemporary writers. Catherynne M. Valente may not be, but I wouldn’t even be thinking about the comparison if Gaiman’s endorsement were absent from the cover. Her The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making is clever, well-plotted, engaging, and inventive. It’s not Gaiman, but it is good.

Better points of comparison are L. Frank Baum and J.M. Barrie. As Barrie does in Peter and Wendy, Valente several times calls children “heartless,” and deploys a narrative voice that shifts between third person, second person, and first person – though it stays mostly in third. As Barrie’s narrator does, Valente’s invokes that heartlessness to consider the child’s desire to abandon home for fairyland: “September did not even wave good-bye. One ought not to judge her: All children are heartless.” That said, and again following Barrie’s example, Valente does invite us to judge her protagonist. As many parents are, these narrators are torn between granting the child her freedom and keeping her close by.

Instead of being transported from Kansas via tornado, 12-year-old September gets whisked away from Nebraska by the Leopard of Little Breezes. Also bringing to mind the Oz books, Valente’s fantastic characters combine nature and machinery in ways that recall Baum’s. There’s Lye, a golem made of soap; Gleam, a lamp that speaks through messages on its shade; and herds of velocipedes (free-range bicycles). Valente also seems to have taken seriously Baum’s goal (in his introduction to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz) to strive for a “a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heart-aches and nightmares are left out.” Valente’s tone suggests that the “good” characters will not come to any harm. That said, and as is also true of Baum, by about halfway through the book, much that threatens the heroine seems to revoke the promise of a nightmare-free story. As the narrator observes, “I have tried to be a generous narrator and care for my girl as best I can. I cannot help that readers will always insist on adventures, and though you can have grief without adventures, you cannot have adventures without grief.”

In discussing a few of the many works that likely inspired The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of her Own Making, I do not mean here to deride the book as “derivative.” All art derives from other art. What makes something feel original is the way in which it combines all that inspired it. Neil Gaiman’s books do this work seamlessly. Transformed by his imagination, his influences feel organic. They don’t feel like influences at all. To read a Gaiman novel is to get caught up in his world – you may catch allusions to Norse mythology, or Victorian writer Lucy Clifford, but the feeling is something fashioned out of whole cloth.

This is not entirely the case with Valente, though the garrulous narrator may be partially the cause. Fond of shifting out of third person and offering editorial comments, the narrative voice prevents readers from becoming too absorbed in the story. Pushing its audience way from such absorption, The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of her Own Making instead gives them space to think about the narrative, the allusions, the books that seem to be Valente’s favorites. As fans of Lemony Snicket know, such a narrator can also be fun to spend time with. He (or she) treats the reader like a confidante, suggesting an intimate, even privileged, relationship with the person holding the book. Valente’s narrator is not only good company; she (or he) is wise, witty, and unpredictable. As she (he?) admits late in the novel, “I am a sly and wicked narrator. If there is a secret to be plumbed for your benefit, Dear Reader, I shall strap on a head-lamp and a pick-ax and have at it.”

In this review, I’ve deliberately avoided “secrets”: narrative is one of the many pleasures of The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairlyand in a Ship of Her Own Making. So, you’ll find no spoilers here. Featuring a female lead who is both thoughtful and brave, the book is a fantasy that offers a meditation on fantasy’s tropes. As Dumbledore does in the Harry Potter series, this novel too dismisses the idea that its hero is a “chosen one.” Late in the book, one of September’s allies remarks, “You are not the chosen one, September. Fairyland did not choose you – you chose yourself.”

Should you choose to read Valente’s novel, you’ll find it a smart, metafictive tale, with plenty of adventure, humor, and insight. Neil Gaiman calls it “A glorious balancing act between modernism and the Victorian fairy tale, done with heart and wisdom.” He’s right.

Monica Edinger

jules

Philip Nel

Sam bloom

Richard Flynn