Soon after its publication in the fall of 1936, the title character of Munro Leaf’s Ferdinand began to take on a life of his own. Since the story is set in Spain and the book appeared just months after the start of the Spanish Civil War, people began to speculate on Ferdinand’s political allegiance, labeling him variously as pacifist, Communist, anti-Communist, Fascist, and anti-Fascist. Leaf insisted that he was just a bull who preferred smelling flowers, and nothing more. But Ferdinand had entered the public imagination, and began to accrue a range of meanings unimagined by Leaf or Robert Lawson, the book’s illustrator. He became a balloon in Macy’s Thanksgiving parade. In 1938, Slim and Slam (of “Flat Foot Floogie” fame) sang of “Ferdinand, the Bull with the delicate ego.”

That same year, Walt Disney released a hit animated adaptation of the book. During World War II, Australians spotting Japanese ships named themselves “Ferdinands” (because they sat up in the hills watching). Hitler banned the book; Franco prohibited its publication; Gandhi admired it. Stalin named an artillery piece the  Ferdinand (because the gun was a peacemaker). Ernest Hemingway wrote “The Faithful Bull” (1951) in response to Ferdinand. The late singer-songwriter Elliott Smith (Oscar-nominated for “Miss Misery”) had a tattoo of Ferdinand on his arm – you can see it on the cover of his album, either/or (1997). On 20 September 2007, 258,000 children around the U.S. read Ferdinand as part of “Read for the Record,” a literacy campaign sponsored by JumpStart. And this is only some of what Ferdinand has inspired in its first 75 years.

Ferdinand (because the gun was a peacemaker). Ernest Hemingway wrote “The Faithful Bull” (1951) in response to Ferdinand. The late singer-songwriter Elliott Smith (Oscar-nominated for “Miss Misery”) had a tattoo of Ferdinand on his arm – you can see it on the cover of his album, either/or (1997). On 20 September 2007, 258,000 children around the U.S. read Ferdinand as part of “Read for the Record,” a literacy campaign sponsored by JumpStart. And this is only some of what Ferdinand has inspired in its first 75 years.

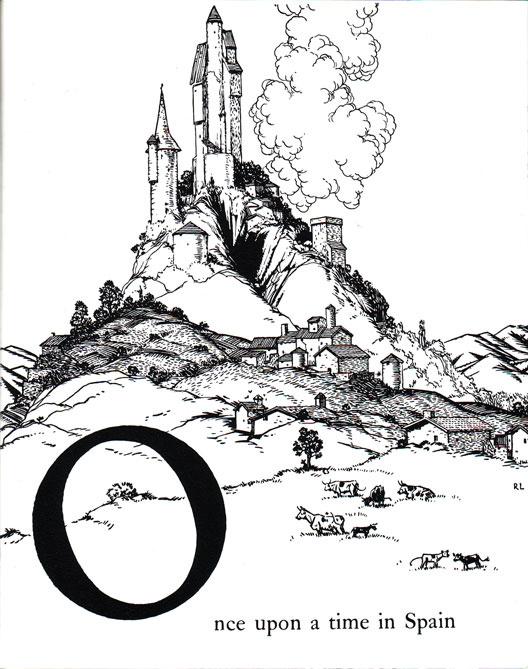

The story’s opening sentence inspired readers to draw comparisons between Ferdinand and its contemporary political context – the Spanish Civil War. In July of 1936, Franco’s fascist troops invaded Spain, intent on overthrowing the democratic Spanish Republic. In September of 1936, the Viking Press published The Story of Ferdinand. In 1937, readers accused Ferdinand of being, alternately, Communist, Fascist, Pacifist, anti-Communist, and anti-Fascist. Why?

The story’s opening sentence inspired readers to draw comparisons between Ferdinand and its contemporary political context – the Spanish Civil War. In July of 1936, Franco’s fascist troops invaded Spain, intent on overthrowing the democratic Spanish Republic. In September of 1936, the Viking Press published The Story of Ferdinand. In 1937, readers accused Ferdinand of being, alternately, Communist, Fascist, Pacifist, anti-Communist, and anti-Fascist. Why?

In Spain, after Franco’s invasion, the working classes organized, collectivized the land, formed workers militias, dismantled the church (which was pro-fascist), and took its land. They became known as the Loyalists because they were loyal to the Spanish Republic. Stalin sent military and political advisers to help the Loyalists. Mussolini and Hitler pledged assistance to Franco. In the U.S., left-leaning people of diverse political allegiances – liberals, Socialists, Communists – sent aid to the Loyalists. The North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, chaired by Bishop Francis J. McConnell, raised over $1 million. Americans sent 175 ambulances, and maintained eight hospitals with 125 American doctors and nurses. They also sent food and clothing. The Abraham Lincoln Brigade – 2,800 American volunteers, some 60% of whom were members of the Communist Party or Young Communist League – went to Spain to fight against Franco and his fascist allies. Ernest Hemingway, Lilian Hellman, and others wrote sympathetic articles about the brigade. Those U.S citizens who fought for a democratic Spain were the first Americans to join the fight against fascism – doing so in 1937 and 1938, three to four years before the U.S. got involved in what became the Second World War.

Reading Ferdinand as being specifically about Spain, a reader of 1936-1937 might see the book as Communist or anti-Fascist: Ferdinand takes control of his own destiny by opposing the wishes of the “Fascist” bullfighting community. The self-determined bull then stands in for the Loyalists and their supporters (Communists, Socialists, liberals). An alternate reading could figure Ferdinand as Pacifist because his defining characteristic is refusing to fight. No matter how much the bullfighters try to entice him, Ferdinand just sits and smells the flowers. According to this logic, Ferdinand is a Pacifist. A third approach would be to argue that Ferdinand’s decision not to battle his opponents is analogous to caving to Fascist demands. Though Ferdinand ends happily, in the Spain of 1936 and 1937, a failure to fight would mean certain victory by the Fascists.

The debate over whose “side” Ferdinand supports reflects the ways in which context creates meaning. Scholar Constance B. Hieatt suggests that people interpreted Ferdinand as pacifist because “he still liked to sit just quietly under the cork tree and smell the flowers” offered a Biblical allusion to Micah 4: “And he shall judge among many people, and rebuke strong nations afar and off; and they shall beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall not lift up a sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more. But they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree.” In Ferdinand, she writes, “the fig tree is replaced by a cork tree.” Switch the context from the Bible to gender, and we might arrive at the conclusion that the book supports the choices of those who depart from gendered norms. Our narrator remarks, “All the other little bulls he lived with would run and jump and butt their heads together, but not Ferdinand.” Male bulls, like male humans, are expected to be aggressive. Ferdinand isn’t. When his mother asks why he doesn’t join them, Ferdinand explains, “I like it better here where I can sit just quietly and smell the flowers.” An “understanding mother,” she “let him just sit there and be happy.” In this sense, Ferdinand suggests that parents ought to support their children, irrespective of whether those children conform to social expectations about gender.

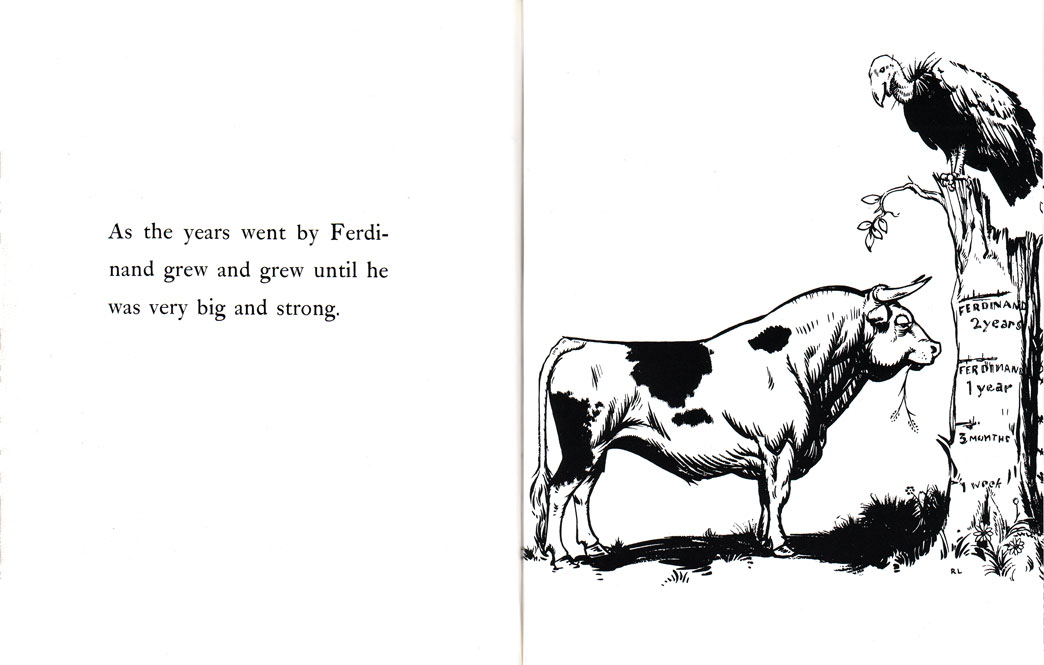

Focus on those vultures, and The Story of Ferdinand becomes a tale about mortality. Robert Lawson’s pictures introduce the vultures, recurring characters never mentioned in Leaf’s text. This productive tension between Leaf’s text and Lawson’s illustrations creates a rich reading experience, as the contributions of author and artist interact. Against the claim (aided by Lawson’s portrait of Ferdinand) that the bull “grew and grew until he was very big and strong,” the vulture portends death. Inasmuch as the marks ascending the tree trunk record the passage of time (“1 week” “3 months,” “1 year,” “2 years”), the vulture at the top suggests Ferdinand’s inevitable death. That the vulture is the next “marker” after only “2 years,” however, suggests that Ferdinand may die soon – as he would, if he were to participate in a bull fight. On the next two-page spread, the other bulls look at a “BULL FIGHT” poster as they aspire to be selected for the fight, not noticing the two vultures atop the roof. The bulls’ failure to see the vultures suggests a youthful unawareness of the fate in store for the chosen bull. Eighteen pages later, when Ferdinand, in a cart, heads to “the bull fight day,” a vulture stands atop the “Madrid” sign. Given that the cart is headed to the ring in Madrid, Lawson implies that Ferdinand is also heading to face his mortality. On the following two-page spread, when “Flags were flying, bands were playing…” two vultures sit atop a roof, providing a dark contrast to the celebratory mood. As silent but persistent witnesses to the book’s narrative, the vultures offer an ominous subtext and suggest the life of Ferdinand may end with his story. When we read, we interpret, and the context through which we interpret shapes what we see.

Munro Leaf always maintained that Ferdinand was not political. He said that the book was “the story of a Spanish bull that refused to go into the arena to fight – so they had to send him back home, where he settled down again to smelling the flowers.” In response to the controversy, he said, “I have been accused of defending or attacking practically every ‘ism’ that has popped up in the last few years. As far as I am concerned, there is one story there – the words are simple and quite short. They try to make sense and if there is a message in them, as many people seem to want, it is Ferdinand’s message, not mine – get it from him according to your need.”

Leaf’s wife and son have both suggested that Ferdinand’s message is the author’s – that it’s autobiographical. Gil Leaf once said of his father, “He’d do his own thing. He told his mother when he was 12 years old that when he grew up he was not going to work for anybody else.” On the occasion of Ferdinand’s fiftieth birthday, Margaret Leaf wrote of her late husband, “Munro always maintained that he meant no message, that he meant only to entertain. But I have a photo of him as a small boy lying down in front of a family group, and he is smelling a flower.”

Special Thanks to Gil Leaf for taking the time to talk with me about his father, and for supporting my Annotated Ferdinand project – which never found a publisher, and from which the preceding essay derives.

There have been several other tributes to Ferdinand in his 75th year. I neglected to consult them while assembling this… largely because the above was adapted from the (failed) book proposal I wrote four years ago! Here are the two best ones:

- Pamela Paul, “Ferdinand the Bull Turns 75.” New York Times, 31 Mar. 2011: <http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/03/31/ferdinand-the-bull-turns-75/>.

- Anita Silvey, “The Story of Ferdinand.” Anita Silvey’s Book-a-Day Almanac, 18 July 2011: <http://childrensbookalmanac.com/2011/07/the-story-of-ferdinand/>.

Works Consulted

“About Ferdinand.” Publishers Weekly 22 Aug. 1966: 54-55.

A.T.E. Review of The Story of Ferdinand. New York Times Book Review 15 Nov. 1936: 41.

Buhle, Mari Jo, Paul Buhle, and Dan Georgakas, editors. Encyclopedia of the American Left. Second Edition. New York and Oxford: Oxford UP, 1998.

Denning, Michael. The Cultural Front. London and New York: Verso, 1996.

“Ferdinand.” New York Times 20 Nov. 1937: 16.

Hearn, Michael Patrick. “Ferdinand the Bull’s 50th Anniversary.” Washington Post Book World 9 Nov. 1986: 13, 22.

Hieatt, Constance B. “Analyzing Enchantment: Fantasy After Bettelheim.” Canadian Children’s Literature 15-16 (1980): 6-14.

Leaf, [James] Gil. Telephone interview with Philip Nel. 29 Sept. 2003.

—. Telephone interview with Philip Nel. 1 June 2006.

Leaf, Margaret. “Happy Birthday, Ferdinand!” Publishers Weekly 31 Oct. 1986: 33.

Leaf, Munro. Being an American Can Be Fun. Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1964.

—. How to Behave and Why. Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1946.

—. The Story of Ferdinand. Illus. Robert Lawson. 1936. New York: Puffin Books, 1977.

—. A War-Time Handbook for Young Americans. Philadelphia and New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1942.

Steig, Michael. “Ferdinand and Wee Gillis at Half-Century.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 14.3 (Fall 1989): 118-123.

“(Wilbur) Munro Leaf.” Contemporary Authors Online. The Gale Group, 2000. Literature Resource Center.

“Writer for Young Tells of New Woes.” New York Times 18 Nov. 1937: 21.

Ariel Cooke

Philip Nel

Pingback: Illustration Daily – Day 111: The Story of Ferdinand – Kat Kins Art

Pingback: Module 2: The Story of Ferdinand | Ms. Roye's Book Corner

Pingback: My Friend, Ferdinand | Under The Cork Tree