Bumble-Ardy gets adopted by his Aunt Adeline after his “immediate family gorged and gained weight. / And got ate.” When he throws himself a birthday party without her permission, Aunt Adeline threatens his guests: “Scat, get lost, vamoose, just scram! / Or else I’ll slice you into ham!” On the next two-page spread, Bumble tells his aunt, “I promise! I swear! I won’t ever turn ten!” There are other jokes about – and references to – death in Bumble-Ardy. One reason for this theme may be that Maurice Sendak’s new picture book is a celebration of mortality. It sings us the “Happy Birthday” song, but changes the lyrics to We’re all gonna die!

Bumble-Ardy is a genuinely jubilant book. Its thematically death-saturated commemoration of its title character’s ninth birthday is not gloomy. If it inadvertently evokes the early Christian practice of celebrating deathdays,1 that’s likely because its 83-year-old author understands what its nine-year-old protagonist does not: each birthday brings us one year closer to our death. As is the case with other Sendak heroes (such as Where the Wild Things Are’s Max, and In the Night Kitchen’s Mickey), Bumble is a version of his creator. They share a birthday of June 10th – Sendak was born in 1928, and Bumble (according to the book) in 2000. Reinforcing this connection, Sendak repeats the date four times on the opening three pages, each with a different year.

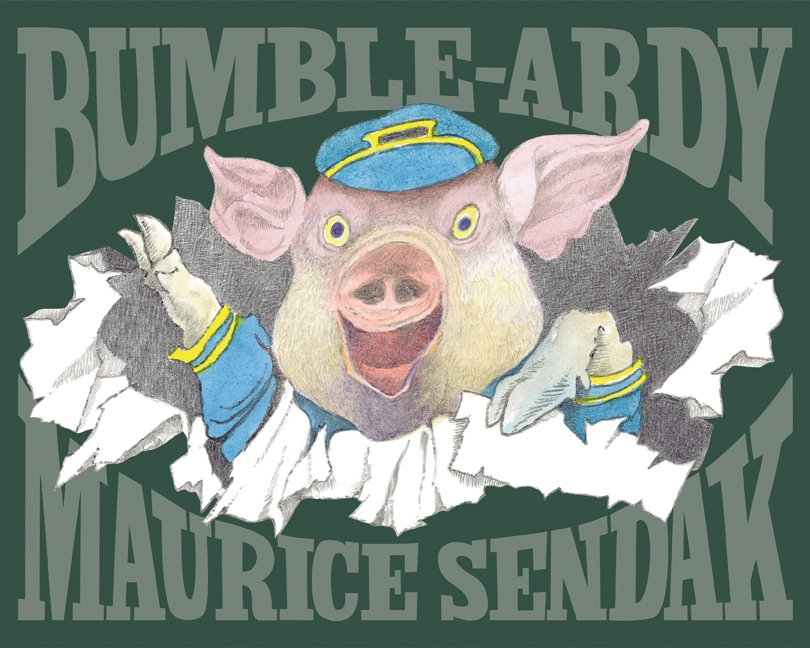

On the title page, the birthday’s fourth and final appearance is June 10, 2008. That was a significant date and year for Sendak: he turned 80, had a triple-bypass that temporarily left him too weak to work or walk his dog, and mourned the passing of his partner of more than 50 years, Dr. Eugene Glynn. Though Dr. Glynn died in May of the previous year, in 2008 Sendak spoke publicly about his sexuality for the first time. Asked by the New York Times whether there were anything he had never been asked, Sendak answered, “Well, that I’m gay.” It’s tempting to see Bumble – as he bursts through the June 2008 calendar on the title page and shouts “Well!” – as an echo of Sendak’s declaration of his own sexual identity.

But biographical interpretations are tricky, and ultimately limiting. While all artists’ lives influence their works, no work is purely a reflection of its creator’s autobiography. All art offers indications elsewhere, ideas and themes that cannot be reduced to a life history. In this book, two pigs carry a banner reading “SOME SWILL PIG,” evoking Charlotte’s “SOME PIG” in E.B. White’s classic novel. On the page before the title page, Bumble reads the Hogwash Gazette, which announces “WE READ BANNED BOOKS!” – an allusion, perhaps, to In the Night Kitchen’s status as a banned book. The masquerade party itself seems a more chaotic, more artistically eclectic version of Rosie’s backyard show in The Sign on Rosie’s Door. (Incidentally, like Lenny in that book, Bumble also wears a cowboy hat.)

At the party, one of Bumble’s guests comes dressed as death – skull mask, skeletal costume beneath a black cloak – but carries a banner wishing Bumble long life. “MAY BUMBLE LIVE 900 YEARS!” it proclaims. And that’s the heart of this book. It knows that death will come later or sooner, but it’s willing to celebrate while it can.

1. Early Christians thought it would be sinful to observe the birth of Christ or of saints, as doing so would continue the pagan practices of the Egyptians and Greeks. One should instead (they thought) celebrate the day on which a saint ascended to heaven. Around the 4th century AD, they began to change their mind, paving the way for the celebration of Christmas. See Charles Panati’s Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (1987), p. 33.

mta

Philip Nel

Pingback: Fusenews: She could be Fuse #8.1 « A Fuse #8 Production

leda