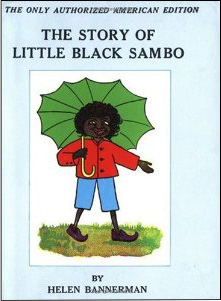

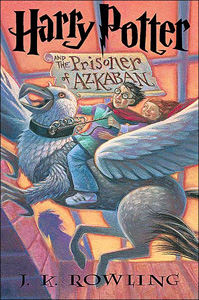

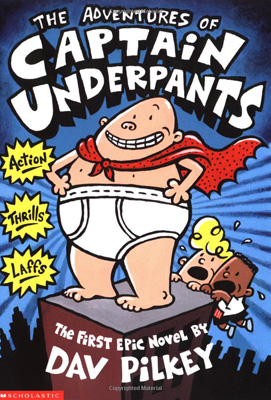

Sometimes, a new course draws on my expertise. Other times, a new course is a chance for me to develop that expertise. This class — “Censoring Children’s Literature” — is definitely the latter. I have an interest in the subject, and I’ve tried to structure the syllabus around major issues concerning the regulation of what children and young adults read: texts that have been Bowdlerized so as not to offend current sensitivities, texts altered without the author’s consent, texts over which there’s a documented scuffle between author and publisher, and of course the many reasons that adults may deem a text unsuitable for children or adolescents (profanity, sex, homosexuality, racism, religion, and so on). But I’m definitely not an expert on the subject.

Sometimes, a new course draws on my expertise. Other times, a new course is a chance for me to develop that expertise. This class — “Censoring Children’s Literature” — is definitely the latter. I have an interest in the subject, and I’ve tried to structure the syllabus around major issues concerning the regulation of what children and young adults read: texts that have been Bowdlerized so as not to offend current sensitivities, texts altered without the author’s consent, texts over which there’s a documented scuffle between author and publisher, and of course the many reasons that adults may deem a text unsuitable for children or adolescents (profanity, sex, homosexuality, racism, religion, and so on). But I’m definitely not an expert on the subject.

The class is called “Censoring Children’s Literature” because that’s what fit on the university’s line schedule. A more accurate title would be “What You Can and Can’t Say in Literature for Children and Young Adults.” In other words, rather than framing the class around “censorship” exclusively, I also recognize there are reasons to be concerned about what children read – they lack the experience of adults, their identities are in the process of being formed, and one may fairly consider them more impressionable than older readers. Certainly, one does not want to scar children emotionally, nor teach them to hate. On the flip side, part of growing up is learning to cope with a world that can seem indifferent to your troubles: literature can help you explore these troubles imaginatively.

The class is called “Censoring Children’s Literature” because that’s what fit on the university’s line schedule. A more accurate title would be “What You Can and Can’t Say in Literature for Children and Young Adults.” In other words, rather than framing the class around “censorship” exclusively, I also recognize there are reasons to be concerned about what children read – they lack the experience of adults, their identities are in the process of being formed, and one may fairly consider them more impressionable than older readers. Certainly, one does not want to scar children emotionally, nor teach them to hate. On the flip side, part of growing up is learning to cope with a world that can seem indifferent to your troubles: literature can help you explore these troubles imaginatively.

And, then, there’s the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: “Congress shall make no law […] abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” In other words, it’s one thing to seek to prevent your own children from reading a work you consider inappropriate, and it’s another thing to decide – on behalf of an entire school district or public library – that no children should have access to the work.

And, then, there’s the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: “Congress shall make no law […] abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” In other words, it’s one thing to seek to prevent your own children from reading a work you consider inappropriate, and it’s another thing to decide – on behalf of an entire school district or public library – that no children should have access to the work.

I expect the class to disagree about what books are and are not appropriate for younger readers. That disagreement is part of the point of having this conversation in the first place. Discerning how “the average person, applying contemporary community standards” — to quote the landmark obscenity ruling Roth v. United States (1957) — might perceive a book is a tricky business. But I am and have always been drawn to the difficult questions, the grey areas of a debate, the problems without clear solutions. So. Let the conversation begin!

I expect the class to disagree about what books are and are not appropriate for younger readers. That disagreement is part of the point of having this conversation in the first place. Discerning how “the average person, applying contemporary community standards” — to quote the landmark obscenity ruling Roth v. United States (1957) — might perceive a book is a tricky business. But I am and have always been drawn to the difficult questions, the grey areas of a debate, the problems without clear solutions. So. Let the conversation begin!

Maria Nikolajeva

Philip Nel

Kay Weisman

Philip Nel

Kenneth Kidd

Philip Nel

Pingback: Fusenews « A Fuse #8 Production

Debbie Reese

Claudia Pearson

Claudia Pearson

Philip Nel

Louise

Pingback: You Can Censor Children’s Literature, But Can You Erase Ideology?

Joseph T. Thomas, Jr.