“What do you want to be when you grow up?”

“Happy,” said Thomas. “When I grow up, I am going to be happy.”

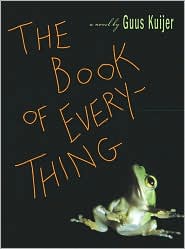

Nine-year-old Thomas sees things that others don’t, like “tropical fish swimming in the canals,” thousands of frogs massing outside his house, and the loveliness of sixteen-year-old Eliza, who has “an artificial leg made of leather” and seems to understand him. Guus Kuijer’s The Book of Everything (2004, translated by John Nieuwenhuizen, 2006) is a brief, beautiful tale of Thomas losing faith, making friends with his sister and Mrs. van Amersfoort, gaining confidence in himself, and learning to resist his father’s bullying. The prose is lyrical, the images are magical realist, and the story is full of wisdom and humor.  Here is a passage when Thomas, visiting Mrs. van Amersfoort, listens to Beethoven for the first time (the second sentence refers to her cat, who has been napping on a globe):

Nine-year-old Thomas sees things that others don’t, like “tropical fish swimming in the canals,” thousands of frogs massing outside his house, and the loveliness of sixteen-year-old Eliza, who has “an artificial leg made of leather” and seems to understand him. Guus Kuijer’s The Book of Everything (2004, translated by John Nieuwenhuizen, 2006) is a brief, beautiful tale of Thomas losing faith, making friends with his sister and Mrs. van Amersfoort, gaining confidence in himself, and learning to resist his father’s bullying. The prose is lyrical, the images are magical realist, and the story is full of wisdom and humor.  Here is a passage when Thomas, visiting Mrs. van Amersfoort, listens to Beethoven for the first time (the second sentence refers to her cat, who has been napping on a globe):

His ears started ringing again. The globe started spinning, cat and all. When he was about to draw Mrs. van Amersfoort’s attention to this, he saw that her heavy chair was floating above the floor like a low cloud. He barely had time to take this in when he felt the chair he was sitting in rising slowly, as if strong hands were lifting it. He wanted to shout with joy, but when he saw Mrs. van Amersfoort’s intent face, he realized that, with this music, it was normal for chairs to float. (19)

I love how this translates Thomas’s sense of wonder into a literal, physical experience. Kuijer does not tell us that Beethoven’s music makes them feel as if they were floating. Instead, they just float, borne upward in their chairs, drifting like low clouds. Beautiful.

The Book of Everything won the Flemish Golden Owl Award, but is not widely known in this country. It’s really, really good. I highly recommend it. I suspect that, once you read it, you’ll recommend it, too.