Children’s literature is literature. Intelligent adults already know this. However, as those of you who study or write or teach children’s literature are well aware, the world is full of alleged grown-ups who insist on spreading the myth that children’s literature is not literature, and (thus) cannot be studied as such.

Children’s literature is literature. Intelligent adults already know this. However, as those of you who study or write or teach children’s literature are well aware, the world is full of alleged grown-ups who insist on spreading the myth that children’s literature is not literature, and (thus) cannot be studied as such.

A week or so back, journalist Alison Flood reported on a conference alleged to be “Billed as the world’s first conference to discuss Harry Potter strictly as a literary text.” Presumably, that’s a swipe at the fan-organized conferences, the first of which was (I believe) Nimbus 2003: The Harry Potter Symposium, held nearly 9 years ago. While fan conferences do discuss the books as literary texts, it’s also true that they cover other, less traditionally “academic” subjects. (Full disclosure: I’ve been an invited speaker at two of the fan conferences, including Nimbus 2003.) However, it seems a bit of a stretch to say that this was “the world’s first conference to discuss Harry Potter strictly as a literary text.” It was not.

Ms. Flood also seems unaware of the vast body of scholarship on Rowling’s series – which Cornelia Remi has for years diligently tracked on her exemplary bibliography.  While Potter scholarship does vary in quality, the ignorance of Professor John Mullan – who is quoted in the article – is truly exemplary. There’s a rare purity in his empty prejudices, shaped without knowledge or reflection. According to Flood’s article, Mullan said, “I’m not against Harry Potter, my children loved it, [but] Harry Potter is for children, not for grownups…. It’s all the fault of cultural studies: anything that is consumed with any appearance of appetite by people becomes an object of academic study.” Professor Mullan concludes that the academics attending the conference “should be reading Milton and Tristram Shandy: that’s what they’re paid to do.” In one sense, it’s apt that a poorly informed article would be supported with a quotation from a poorly informed academic. In another sense, one might pity Mullan and Flood for being ill-equipped to complete their tasks – in his case, intelligent commentary, and, in hers, responsible journalism. As Clementine Beauvais noted in her report on the conference, “It isn’t just careless, or uninformed, to dismiss the Harry Potter series as a serious object of analysis; it is intellectually dishonest.”

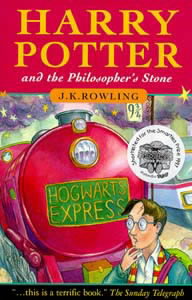

One suspects that Mullan and Flood would be surprised to learn that – in addition to the scores of books and articles about Rowling’s series – a portion of the manuscript for Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Sorcerer’s Stone for American readers) is currently on display in the British Library, alongside works by Chaucer, Edmund Spenser, William Blake, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, Kazuo Ishiguro, Ted Hughes, and George Eliot. Indeed, the exhibit – Writing Britain: Wastelands to Wonderlands – does not segregate children’s literature from “adult literature,” a decision which would likely distress Professor Mullan. In addition to Rowling, the British Library’s exhibit features Kenneth Graham’s Wind in the Willows, A. A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, Arthur Ransom’s Swallowdale, Susan Cooper’s Greenwitch, and Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures Under Ground (the book which, in revised form, became Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland). It also includes comics by Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore. It’s a fascinating, well-curated exhibit.

Rowling’s manuscript pages (written in longhand) display an earlier version of Chapter 6’s first page (67, in the Bloomsbury edition). In the published chapter, the second paragraph begins, “Harry kept to his room with his new owl for company. He had decided to call her Hedwig, a name he had found in A History of Magic” After another three sentences, the paragraph concludes:

Every night before he went to sleep, Harry ticked off another day on the piece of paper he had pinned to the wall, counting down to September the first.

On the last day of August, he thought he’d better speak to his aunt and uncle about getting to King’s Cross station next day, so he went down to the living-room, where they were watching a quiz show on television. He cleared his throat to let them know he was there, and Dudley screamed and ran from the room.

‘Er –Â Uncle Vernon?’

Uncle Vernon grunted to show he was listening.

In Rowling’s handwritten manuscript, the second paragraph begins, “Harry spent most of his time in his room with Widdicombe his owl.” Then, there’s some crossed-out material that’s hard to read with added harder-to-read tiny new material above it, after which Rowling writes:

He pinned a piece of paper on the wall, thinking of the days before he went to September the first marked on it, and he ticked them off every night. On the thirty first of August he thought he’d better speak to his uncle about getting to King’s Cross next day. So he went down to the living room, where the Dursleys were watching a quiz show on television.

Harry cleared his throat to tell them he was there, and Dudley screamed and ran from the room.

“Er – Uncle Vernon?”

Uncle Vernon grunted to show he was listening.

The revisions to the above offer a glimpse into Rowling’s creative process.

Three items stand out.

- First, the original name for Harry’s owl was not Hedwig, but Widdicombe. Hedwig was a medieval saint. Widecombe-in-the-Moor is a town in Devon, England. Ann Widdecombe is a British Conservative Party politician; however, given the distance between Rowling’s views and hers, as well as the close relationship between Harry and his owl, the socially conservative former member of Parliament is likely not the inspiration for the character of Harry’s owl. The town is the most likely source because Rowling collects words she likes, including those from street signs – Snape’s surname came from an English town. The new name for Harry’s owl offers stronger thematic resonances with the character, a noble owl who endures much suffering on Harry’s behalf. The change to the original name also reminds us how carefully Rowling considers her characters’ names. As is the case with Dickens’ names, Rowling’s names often telegraph a key trait of the character.

- Second, based on this selection, Rowling struggles more with descriptive passages than she does with characterization. The books’ sentences – which combine vivid detail with fast-paced narrative – derive from Rowling’s diligent editing. “He pinned a piece of paper on the wall, thinking of the days before September the first marked on it, and he ticked them off every night” becomes “Every night before he went to sleep, Harry ticked off another day on the piece of paper he had pinned to the wall, counting down to September the first.” Though only two words shorter than the earlier version, the published sentence is more sharply constructed. Its opening clause establishes place and time of day, allowing us to visualize where Harry is: “Every night before he went to bed” tells us that he’s in his bedroom, formerly “Dudley’s second bedroom” (32). It also establishes this ticking-off-days as a repeated behavior, occurring “Every night.” Where the original version begins by directing our attention to the paper on the wall, the new version first sets the scene before bringing in the subject of the sentence (our title character) and his nightly activity: “Harry ticked off another day.” It does not need to tell us that he is “thinking of the days before” school begins because the nightly counting-down clearly conveys that the subject is on his mind. The new sentence also ends with “September the first,” placing emphasis on the day Harry awaits, and providing an effective transition to the next sentence, which begins with “the last day of August.”

- Third, I say that characterization comes more easily to Rowling (based on this admittedly limited sample) because she makes very few changes to the descriptions of the Dursleys. In both, they are “watching a quiz show on television,” which (for Rowling) signals their shallowness. Always rude to his nephew, “Uncle Vernon grunted to show he was listening” (in both). Still spooked by his recent encounter with magic, “Dudley screamed and ran from the room” (in both). How apt that Rowling should have greater facility with character. Though she has a fully imagined secondary world, key to readers’ enjoyment are characters to whom they can relate. Rowling’s debt to the mystery genre helps make her books page-turners, but she has such avid fans because she’s able to make people care about Harry, Hermione, Ron, Sirius, Ginny, Dumbledore, Neville, and others.

I concede that my off-the-cuff analysis of a few textual differences could be more robust. But my larger point here is that of course Harry Potter can be –Â and often is –Â the subject of academic analysis. Indeed, for roughly a dozen years, it has attracted a great deal of attention from literary critics. If we are interested in the craft of the most popular and influential writer of her generation, then it’s worth taking J. K. Rowling’s work seriously. If we care about the adults today’s children will become, then we need to take children’s literature seriously. Stories provide children with their earliest ideas about how the world works, and about what literature is and why it matters. Professor Mullan should care about books for the young because the children who enjoy reading are the ones most likely to grow into adults willing to read Laurence Sterne and John Milton. But we all should care about children’s books not merely because they help create literate grown-ups. We should care about them, study them, hold conferences on them, and write them because they are Art.

Links of interest:

- British Library, Writing Britain: Wastelands to Wonderlands

- Cornelia Remi, Harry Potter Bibliography

- My most recent syllabus for Harry Potter’s Library: J. K. Rowling, Texts and Contexts

Priscilla Mizell

kbryna

Ali B

Canzonett

Philip Nel

Keith Hawk

Mary Galbraith

Philip Nel

RA Jones

Pingback: 2014 LIS7210 Library Materials for Children list | sarahpark.com