Welcome to the fifth installment of “Emily’s Library,” in which I list books bought for my 13-month-old niece. As noted in the first entry in this series, my aim is to build for her a kind of “ideal” library of children’s books – understanding, of course, that ideals are impossible, and that my own criteria (see first entry) are fuzzy at best. Despite its shortcomings in theorizing its own criteria, this ongoing list does name good books, and thus may (I hope) be useful to other people seeking books for young readers. (At the end of this blog post, you’ll find links to other resources for finding good children’s books.)

I have not included in my tally (above) works in translation – that is, if a book is listed in both French and English versions, I only count it once (though I do list it below). I do realize that no translation is identical to its original. As Walter Benjamin writes, in translation “the original undergoes a change.” Expanding on that idea, he offers the following simile: “Just as a tangent touches a circle lightly and at but one point, with this touch rather than with the point setting the law according to which it is to continue on its straight path to infinity, a translation touches the original lightly and only at the infinitely small point of the sense, thereupon pursuing its own course according to the laws of fidelity in the freedom of linguistic flux.”1 So, perhaps I should have included translated works in my tally. I didn’t because I feel that, somehow, it’s a limitation of mine – choosing (usually) French translations of English-language originals. I need to find more French-language originals. (As noted in the original “Emily’s Library” post, Emily is being raised in both English and French.) For me, at least, absenting these translations (from the total) signals my list’s deficiencies. Hence, the slight “under-counting.”

Well. On with the list!

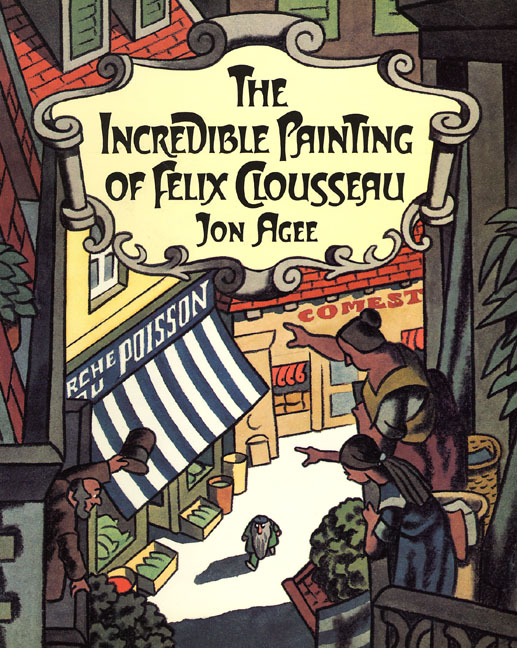

Jon Agee, The Incredible Painting of Felix Clousseau (1988)

Jon Agee, The Incredible Painting of Felix Clousseau (1988)

René Magritte + Ernie Bushmiller = this book by Jon Agee. It’s a comic look at the power of art. It has rival painters whose names are puns on French cuisine. And, as in Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon, the imagination is a source of both possibility and danger. But art is triumphant in the end.

Ludwig Bemelmans, Madeline (1939)

In the first of Bemelmans’ books about Madeline, the title character is small but brave: “not afraid of mice,” says “Pooh-pooh” to the tiger in the zoo, and happily displays her post-appendectomy scar. (Does anyone know why her hair is red in the tiger scene, but blonde in all the other scenes?) In addition to enjoying this book on its own merits, I want to make sure that Emily reads books with strong female characters.

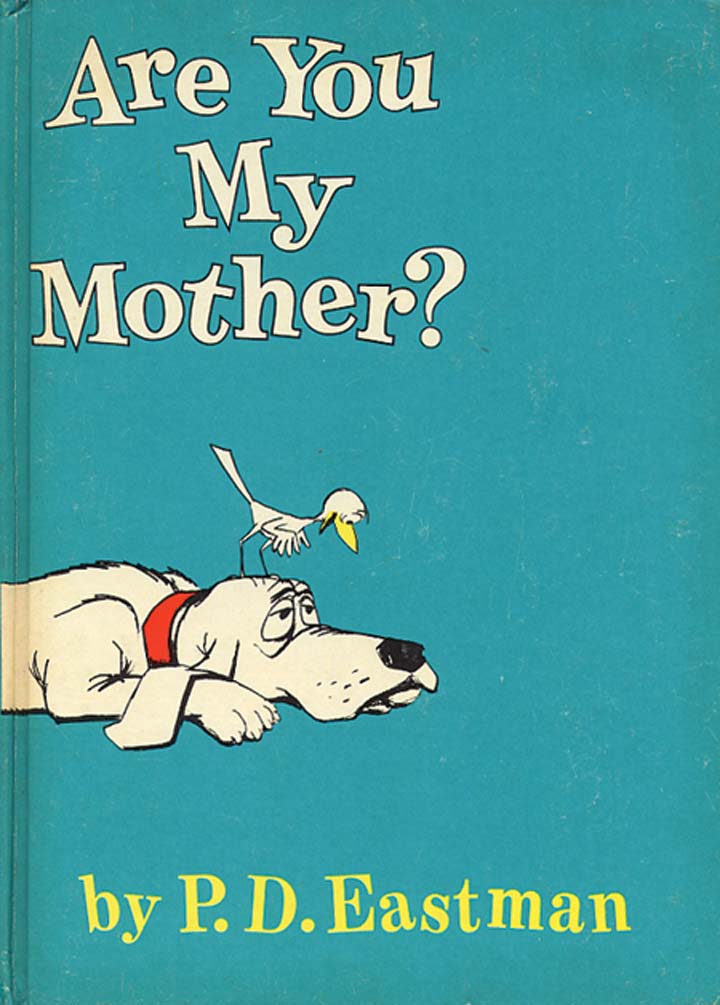

P.D. Eastman, Are You My Mother? (1960)

P.D. Eastman, Are You My Mother? (1960)

A childhood favorite in our family. Favorite line: “‘Oh, you are not my mother,’ said the baby bird. ‘You are a Snort’” (spoken after the baby bird is picked up by an earth mover). For those 1 or 2 people who may not be familiar with this book, a baby bird falls from his nest, and seeks his mother, discovering that kitten, hen, dog, boat, plane, and “Snort” are all not his mother. The repetition of the question to increasingly absurd mother figures is fun (and comic). Of course, baby bird reunites with mother by the end.

P.D. Eastman, Go, Dog. Go! (1961)

An absurdist work, comparable to Dr. Seuss’ One fish two fish red fish blue fish. However, instead of fantastic creatures, Eastman gives us ordinary creatures (dogs) in unusual colors and situations. Sure, the “party hat” dialogue (in which girl dog repeatedly asks boy dog whether he likes her party hat) might interpreted as endorsing the notion that women’s appearance needs to please men – not a great message. On the other hand, the dogs of many colors playing together might be seen as an implicit endorsement of racial diversity (if dogs of different colors play together, so can children of different colors) – a much better message. I think, though, that this was a favorite book of my sister’s (when she was little) because it had lots and lots of dogs. In cars! In trees! On a boat!

Lois Ehlert, Color Farm (1990)

As in Ehlert’s earlier Color Zoo (1989, included on Emily’s Library Part 1), you turn the die-cut pages to see shapes become animals. Bright colors, ingenious design, shows us the hidden geometries of the animal kingdom.

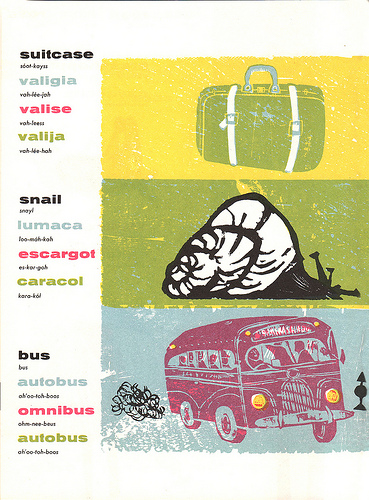

Antonio Frasconi, See and Say / Guarda e Parra / Regarde et Parle / Mira y Habra: A Picture Book in Four Languages (1955)

Ideal for Emily, who is being raised multi-lingual! Frasconi’s book prints a series of objects, each named in in English (printed in black), in Italian (blue), French (red), and Spanish (green). Given that it has an English pronunciation guide for each word (and the word always first appears in English), the book does imagine English-speaking children as its primary audience. However, illustrated by bright woodcuts, the book is great “first words” book for young children, and language education for any age. Used copies are not too hard to find, but this book really ought to be brought back into print.

|

The images above come from The Ward-o-Matic‘s post on the book. Visit the site to see more.

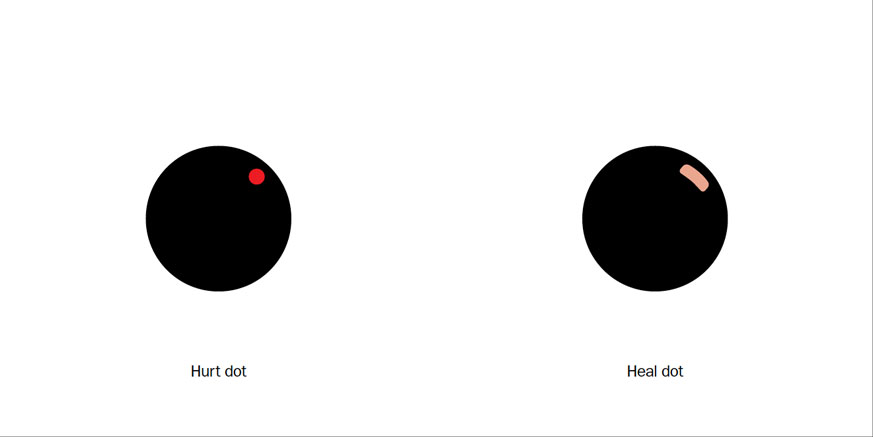

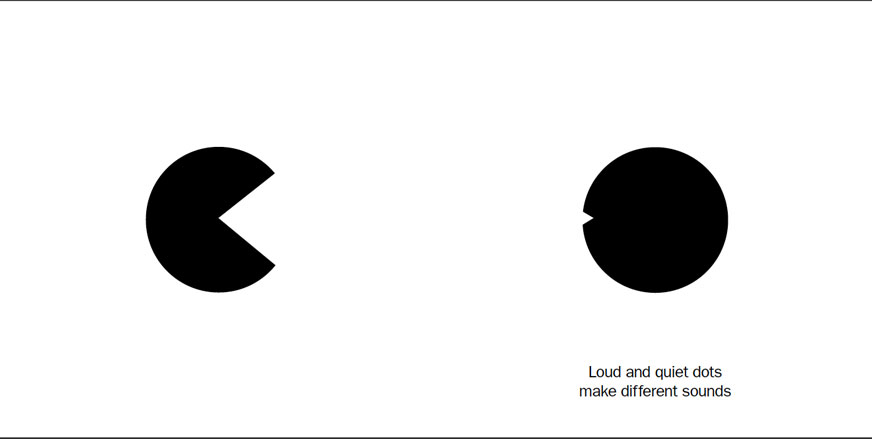

Patricia Intriago, Dot (2011)

A beautifully designed concept book, in which a dot can be slow or fast, bounce up and down, be hungry or full, happy or sad. Or shy. The interaction between word and dot makes this work so well. For “Dot here” on the left page, white words stand out on the upper portion of a large black dot. For “Dot there” on the right page, much smaller black text (on white page) beneath a small dot. In addition to the pun (“Dot” as “That”), the two-page spread conveys the concept so well. It’s almost impossible to convey, in words, the effect of Intriago‘s book. Better if you take a look at a few images.

These images come from Joy Chu’s The Got Story Countdown (scroll down). See also Jules Walker Danielson’s Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast for more on the book.

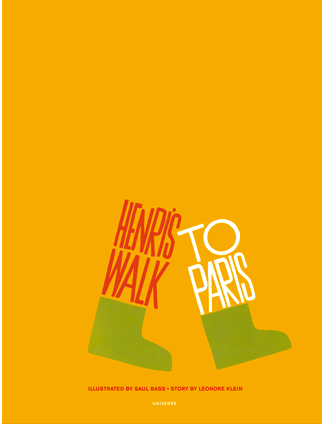

Leonore Klein and Saul Bass, Henri’s Walk to Paris (1962)

Leonore Klein and Saul Bass, Henri’s Walk to Paris (1962)

A beautiful book illustrated (and designed) by Saul Bass, famous for his movie posters and film title sequences. This recently republished book is a visual delight. Its pictures animate the story of little Henri, who sets off for the city, has a nap en route, and, upon waking, resumes his journey… but in the wrong direction.

Ruth Krauss and Maurice Sendak, Bears (2005)

The first version of Krauss’s 26-word story appeared in 1948, with pictures by Phyllis Rowand. In this new version, Maurice Sendak brings back Max (from Where the Wild Things Are) and creates a parallel narrative, in which he (Max) chases a dog to rescue his kidnapped teddy bear. Krauss’s pleasantly absurdist verse and Sendak’s detailed, exuberant illustrations create a great book for young readers. It recalls his early work for children – the Nutshell Library (1962), A Very Special House (1953) and his other collaborations with Krauss.

Edward Lear, The Owl and the Pussy-Cat, illustrated by Ian Beck (1995)

Edward Lear, The Owl and the Pussy-Cat, illustrated by Ian Beck (1995)

“They took some honey, and plenty of money, wrapped up in a five pound note,” which in Beck’s rendering, has a portrait of Edward Lear himself. His version of “the land where the Bong-tree grows” has giant shrubs (or Bong-trees?), all carefully manicured, with the occasional large candy-cane sprouting up in their midst. Beck’s art gently evokes the affection and whimsy in Lear’s interspecies romance.

Leo Lionni, Alexander and the Wind-Up Mouse (1969)

Alexander wishes he were more like Willy, the wind-up mouse whom the children love playing with. Perhaps the magic lizard can change him into a wind-up mouse, too? This, at least, is his wish until he finds that Willy has been tossed into a box of toys that are about to be discarded. As is often the case in Lionni’s stories, Alexander is a fable with a twist. Emily has this book courtesy of her mother’s and my childhood.

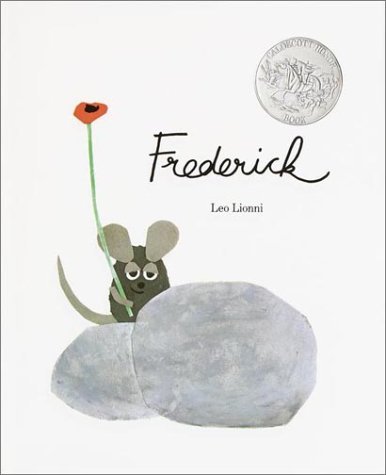

As you read the book for the first time, you might think that Frederick is a version of Aesop’s “The Ant and the Grasshopper”: Frederick is the Grasshopper, gathering no food for the winter; the other mice are industrious like the Ant, preparing for winter’s dearth. Lionni invokes this famous fable in order to upset our expectations. Though Frederick seems lazy, he is in fact gathering the dreams that will sustain his fellow mice through the winter. When their food runs out, they have his art. His words make them feel warm, paint visions in their minds, and give them hope. Lionni’s fable is not a version of “The Ant and the Grasshopper.” It’s about the ways in which art keeps us alive.

Leo Lionni, Frédéric (1975) [Frederick (1967)]

Frederick in French translation.

Leo Lionni, Swimmy (1963)

When Swimmy teaches the little fish to swim in the form of a big fish (with Swimmy as the eye), the many smaller fishes can move throughout the ocean unafraid of the larger fishes – who now see them, collectively, as a single large fish. So, a parable about the power to be gained by organizing? A pro-union fable? Perhaps. According to Leo Lionni, “The central moment is not so much Swimmy’s idea of a large fish composed out of lots of tiny fish but his decision, forcefully stated, that ‘I will be the eye.’ Anyone who knew of my search for the social justification for making Art, for becoming or being an artist, would immediately have grasped what motivated Swimmy, the first embodiment of my alter ego, to tell his scared little friends to swim together like one big fish. ‘Each in his own place,’ Swimmy says, suddenly conscious of the ethical implications of his own place in the crowd. He had seen the image of the large fish in his mind. That was the gift he had received: to see.”2

Robert McCloskey, Make Way for Ducklings (1941)

Robert McCloskey, Make Way for Ducklings (1941)

McCloskey’s classic, in which Mr. and Mrs. Mallard, decide to raise their ducklings on an island in Boston Public Garden. As Leonard Marcus reports in his A Caldecott Celebration (1998), a story (reported in the newspapers) of “a family of ducks that had stopped traffic as it made its way through the nearby streets of Beacon Hill” inspired the story. To make sure that he could draw the ducks to his satisfaction, he studied duck anatomy at the American Museum of Natural History. And he bought sixteen live ducks to live with him and his roommate at the time, Marc Simont. As Simont recalls, this was both noisy and messy, but it enabled McCloskey to draw the bids the way he wanted to. To find out what the underside of a duck looked like in flight, McCloskey “wrapped one of the ducks in a towel and put it so that its head spilled over the couch. Then he lay down on the flor and looked up and sketched it,” Simont told Marcus.3 The result of his efforts was the Caldecott-winning book of 1942.

James Marshall, George and Martha (1972)

James Marshall, George and Martha (1972)

As the book’s subtitle says, Five Stories About Two Great Friends. The first in the series about these two hippos, George and Martha stages gently comic conflicts that conclude with a bit of wisdom. In the final story, while skating to Martha’s house, George “tripped and fell. And he broke off his right front tooth. His favorite tooth too.” The deadpan humor of “His favorite tooth,” amplifies Marshall’s minimalist drawing of a hippo not tripping, but launching himself aloft, suddenly weightless. Though distraught over his lost tooth, George gets a new gold one. When Martha compliments him for looking “so handsome and distinguished” with his new tooth, he says “That’s what friends are for…. [T]hey always know how to cheer you up.” Martha reminds him, “But they also tell you the truth,” and smiles.

James Marshall, George and Martha Encore (1973)

The second (of seven) in the George and Martha books finds George learning to dance, learning French, and failing to disguise himself. Martha forgets her suntan lotion, and has trouble getting her garden to grow.

James Marshall, George and Martha Tons of Fun (1980)

Dedicated to Maurice Sendak, the fifth book focuses more on Martha than George – which, I suppose, may have influenced the dedication. In his introduction to George and Martha: The Complete Stories of Two Best Friends (1997), Sendak “admit[s] to favoring Martha; she never forgets and rarely forgives altogether, and she gets the best Marshall lines” (4).

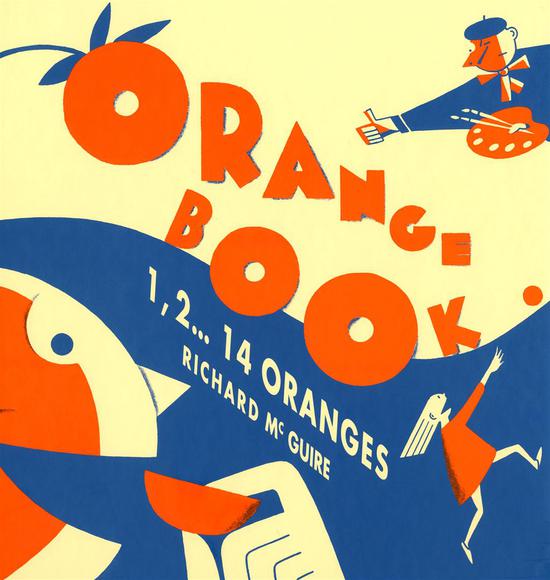

Richard McGuire, The Orange Book (1992)

Limiting his palette to three sharply different colors, McGuire creates concise, strong images. The bright orange spheres and slices almost hover above the surface of cream pages illustrated in blue – orange’s opposite on the color wheel, and likely chosen for maximum contrast. In pages full of visual humor and allusions, the book follows the trajectory of fourteen oranges on their journeys out into the world: “One was sent to a sick friend,” and “Two was used in a juggling act.” In this sense, The Orange Book merely uses the counting-book genre as a frame upon which to explore larger questions. As McGuire has said, the book is “really the story of the paths of life. I guess there is the general idea of ‘interconnectedness,’ too, which interests me.”4 The first of his four picture books, The Orange Book is a visual delight and ought to be brought back into print!

Richard McGuire, Orange Book: 1, 2… 14 Oranges (2001) [The Orange Book (1992)]

French-language translation of McGuire’s The Orange Book. (The cover to this version is above, next to the commentary on the English-language edition.)

My Very First Mother Goose, edited by Iona Opie and illustrated by Rosemary Wells (1996)

My Very First Mother Goose, edited by Iona Opie and illustrated by Rosemary Wells (1996)

Over 100 pages of Mother Goose rhymes, featuring the distinctive bunnies, cats, humans, and other animals of Rosemary Wells. This book and its companion volume Here Comes Mother Goose (1999) – another book I ought to get for Emily – are bright, comic, and big! (Nearly a foot [30 cm.] tall by 10.5 in [26.5 cm.] wide.)

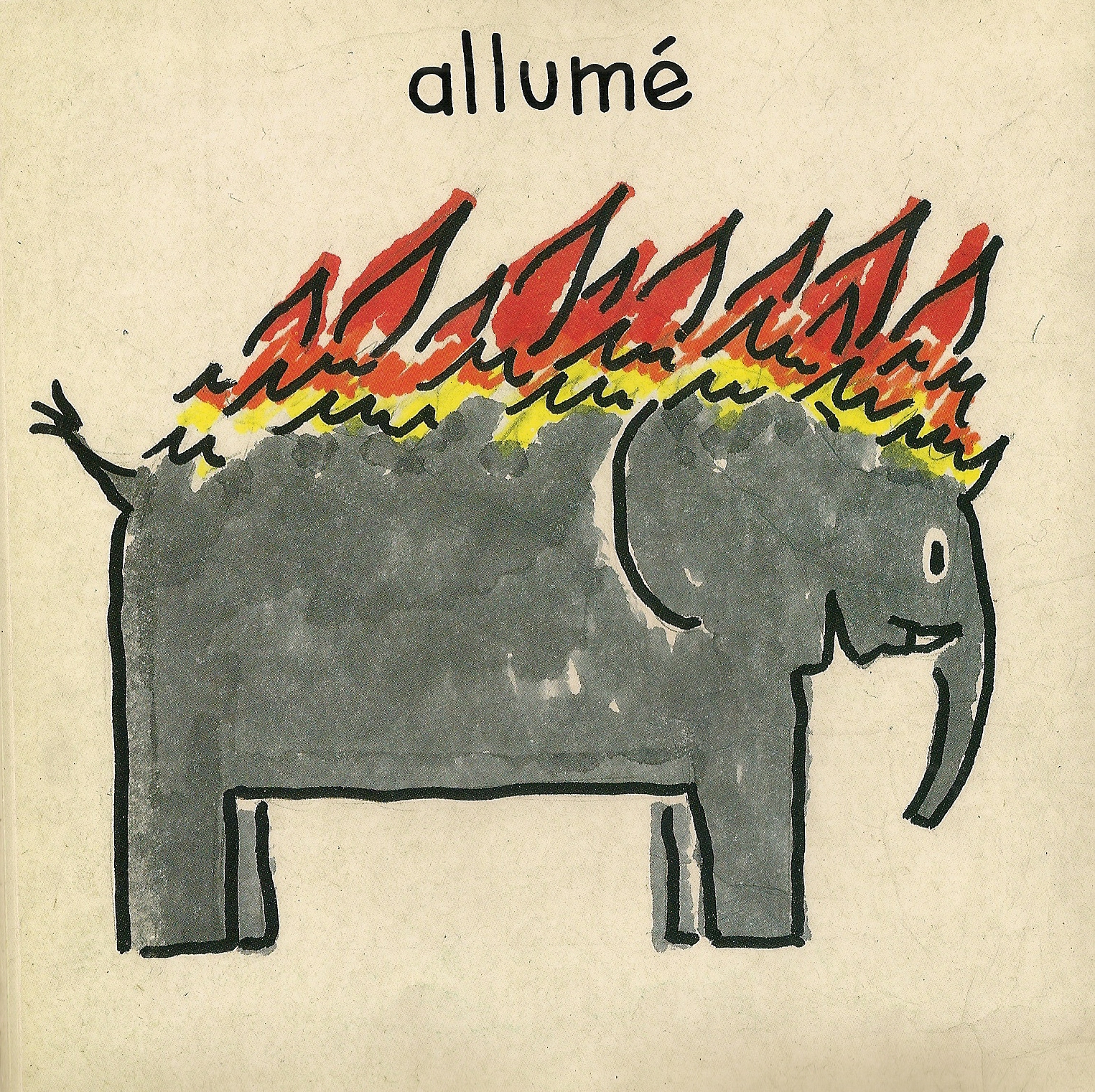

Francesco Pittau & Bernadette Gervais, Les Contraires (1999)

En Français, a humorous exploration of opposites, using the elephant as its unit of measurement. Items such as Big and Small or Long and Short may not surprise. But some of the opposites are a bit… unusual.

|

|

In English, the above are “Lit” and “Extinguished.” Images from Brunette à Paris (and there are more images there, too).

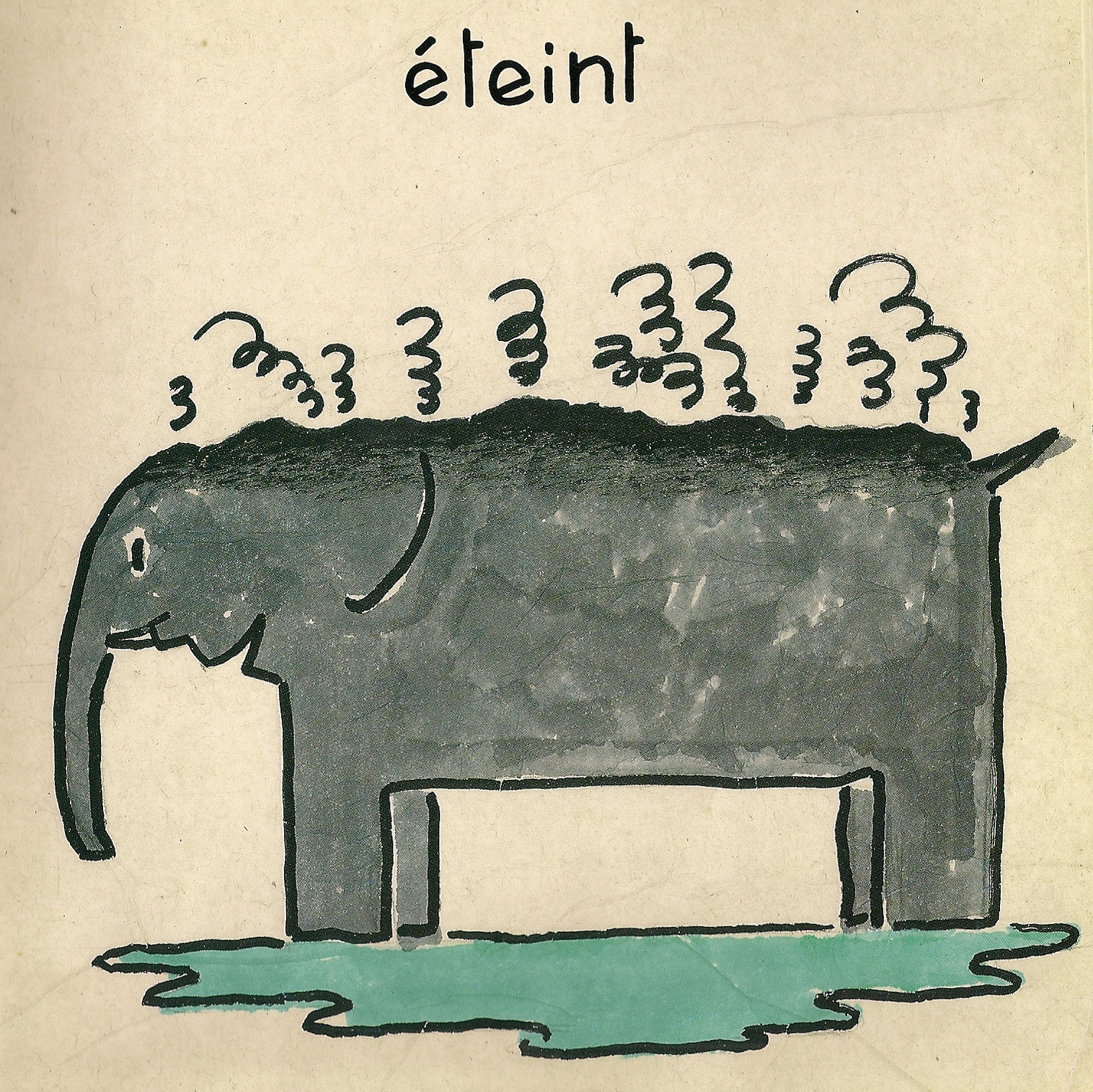

Francesco Pittau & Bernadette Gervais, Elephant Elements (2001) [Les Contraires (1999)]

English-language version of Les Contraires.

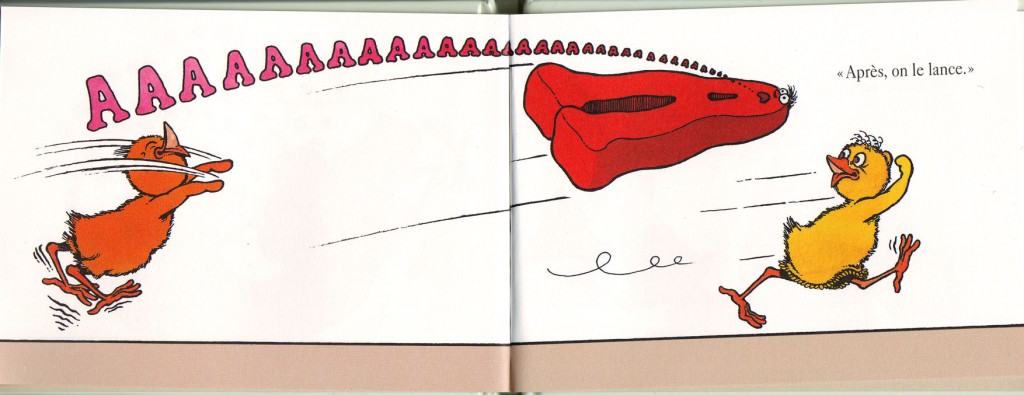

Claude Ponti, Le A (1998)

En Français, Ponti‘s Tromboline et Foulbazar tickle, throw, and poke the letter A. Full of humor and the sound of the A… when it is being tickled, thrown, and poked!

Beatrix Potter, The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902)

Beatrix Potter, The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902)

Another book that reaches Emily courtesy of her mother’s (and my own) childhood, Potter’s classic picture book offers a satisfying combination of suspense, a moral, and dark sense of humor. I particularly like the line “Your Father had an accident there; he was put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor.” Droll. I remember, as a child, being quite worried on Peter’s behalf: how would he get out of Mr. McGregor’s garden? Potter devotes most of the book to Peter either evading McGregor or trying to find his way out once more. Though Peter receives his punishment at the end (getting only chamomile tea, while his sisters get “bread and milk and blackberries for supper”), the fun of the book is his adventure. The well-behaved Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail merely provide a “safe” moral frame for his mischief.

Peggy Rathmann, 10 Minutes Till Bedtime (1998)

Peggy Rathmann, 10 Minutes Till Bedtime (1998)

The countdown to bedtime has rarely been as diverting. As the main character prepares for bed, a tour group of hamsters arrive to see the house. So, of course, these guests must be shown around. Particularly fun are the family of hamsters, each child of which has a different numbered jersey – and a distinct personality. 1 kicks a ball, 2 mimics the protagonist, 7 takes photographs. With each page full of detail, the book offers much for the eyes to explore.

Peggy Rathmann, Au lit dans 10 minutes [10 Minutes Till Bedtime (1998)]

French-language edition of Rathmann‘s 10 Minutes Till Bedtime.

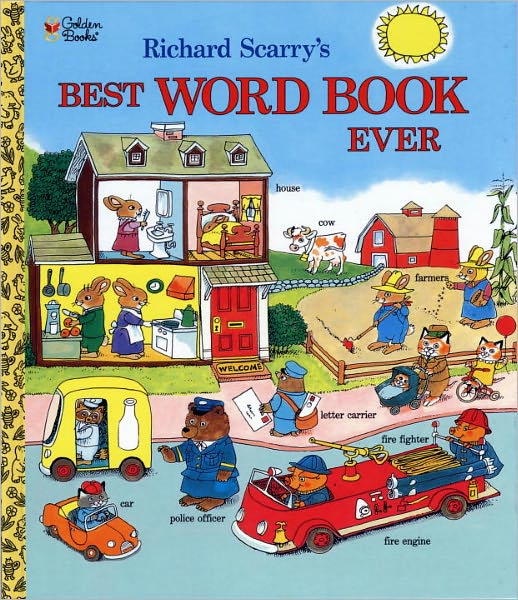

Richard Scarry, Richard Scarry’s Best Word Book Ever, revised edition (1980)

Richard Scarry, Richard Scarry’s Best Word Book Ever, revised edition (1980)

Originally published in 1963, this version modernizes some of the gender roles – both rabbit parents prepare breakfast in the kitchen (instead of just mother), and so on. The extraordinary detail of Scarry’s pictures prompts slow, careful reading. Each two-page spread contains so much detail, each of which bears a label: skyscraper, telephone booth, mail truck, fire hydrant, book reader, and so on. I particularly enjoy the pages that remind us that these clothed animals are in fact stand-ins for clothed humans, as when Scarry takes us to the zoo. Clothed mice children, each of which holds a balloon, visit the elephants, bears, monkeys, and other larger animals. The anthropomorphic cats do not chase the mice: one sells them balloons, another is a zookeeper, and the other is a veterinarian who “makes sure all the animals are healthy.” I was going to buy Emily the French translation as well, but the French version is of the 1963 edition, which preserves all the “traditional” gender roles.

Charles G. Shaw, It Looked Like Spilt Milk (1947)

Like a Rorschach Test, but much more fun. Shaw, a modernist painter with experience in poster design, presents a series of white shapes on a blue background. Each shape resembles something in (white) silhouette – a rabbit, a birthday cake, a tree. This imaginatively engaging concept book does, at the end, tell you what the white shape is: a cloud!

Dr. Seuss, One fish two fish red fish blue fish (1960)

Dr. Seuss, One fish two fish red fish blue fish (1960)

As the first page points out, “From there to here, / from here to there, / funny things / are everywhere.” A concept book (and Beginner Book) of scenes loosely connected by the two children who become recurring characters after the first few fish-centric pages.

Dr. Seuss, Oh, the Thinks You Can Think! (1975)

On a recent business trip to the US, Emily’s mother bought this, Seuss’s ode to the imagination. It’s a celebration of creativity. As the final lines of the book advise, “Think left and think right / and think low and think high. / Oh, the thinks you can think up if only you try!”

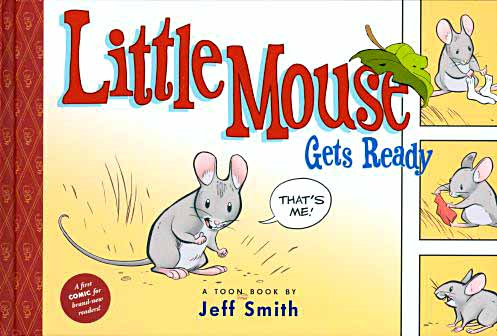

Jeff Smith, Little Mouse Gets Ready (2009)

Jeff Smith, Little Mouse Gets Ready (2009)

In a Geisel Honor book published by Françoise Mouly’s Toon Books, Smith – creator of the graphic-novel epic, Bone – has his title character dressing himself. Told in comics format, smith offers a charming look at one of a child’s first accomplishments (putting on clothes in the right order, managing those buttons!) with a great punch-line at the end… which I will not reveal here.

Ed Young, Seven Blind Mice (1992)

Seven blind mice, each a different color, try to figure out what has arrived near their pond. The reader soon realizes that it’s an elephant, but each mouse successively gets it wrong… until the final mouse. She figures it out. Young‘s book won a Caldecott 1993.

________________________

1. Walter Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator,” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1985), 73, 80.

2. Leo Lionni, Between Worlds (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 232.

3. Leonard Marcus, A Caldecott Celebration (New York: Walker & Company, 1998), 7-8.

4. Thierry Smolderen, “An Interview with Richard McGuire,” Comic Art 8 (Summer 2006), 25.

| When possible, I’ve bought each of these books locally, ordering via Claflin Books & Copies.

Amazon.com is a sweatshop, and (when I can) I prefer to buy from places that are not. |

|---|

Looking for other great children’s books? Try these blogs:

- Elizabeth Bird’s Fuse #8

- Julie Walker Danielson’s Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast

- Anita Silvey’s Children’s Book-a-Day Almanac

Related posts on Nine Kinds of Pie:

- Emily’s Library, Part 1: 62 Great Books for the Very Young (2 Jan. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 2: Wordless Picture Books (3 Jan. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 3: En Français (4 Jan. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 4: Ten Alphabet Books (24 Feb. 2012)

- How to Find Good Children’s Books (April 2011)

- Desert Island Picture Books (Oct. 2011)

- Mock Caldecott, 2011: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2011)

- Mock Caldecott, 2010: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2010)

That’s all for now, but there will be more “Emily’s Library” features.

Anne

Patricia Intriago

Philip Nel