What makes an award-winner?  One of the best picture books of 2008, Kadir Nelson’s We Are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball (2008) won neither the Caldecott Medal nor a Caldecott Honor. The following year, Jerry Pinkney became the first African American to win the Caldecott Medal – “given to the artist of the most distinguished American picture book for children” – for his The Lion & the Mouse (2009).1 That said, We Are the Ship did not come up completely empty-handed.  It did win the Coretta Scott King Author and Illustrator Awards, “given to an African American author and illustrator for outstanding inspirational and educational contributions.”2 And it received plenty of great reviews.  But it should have won the Caldecott.

A lavishly illustrated non-fiction work, Nelson’s We Are the Ship may have missed the Caldecott due to a perception that it is more illustrated book than picture book. However, art gives the book its narrative power, and an interdependent relationship between words and pictures conveys the histories of athletes who, denied participation in the all-white major leagues, displayed their talents in the low-paying but high-performing Negro Leagues. A compelling sports history, We Are the Ship not only was the best picture book of 2008, but is one of the best picture books of the last decade.

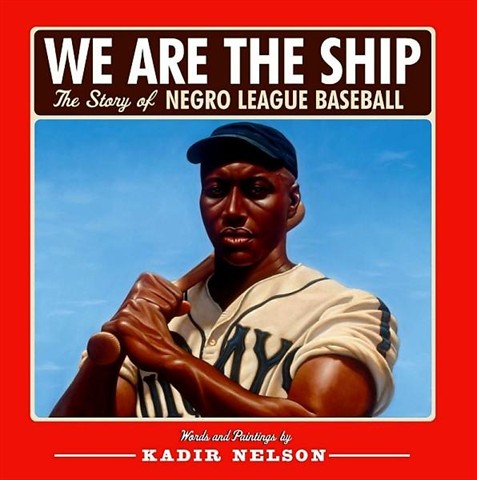

Critics would be correct to point out that, at about 500 words per page, We Are the Ship has far more text than an ordinary picture book; at 88 pages (including index), Nelson’s chronicle is much longer than a typical picture book, which runs 64 or fewer pages. However, the 2008 Caldecott winner The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2007) is over 500 pages, and Nelson’s We Are the Ship succeeds because of “the interdependence of pictures and words,” to quote Barbara Bader’s definition of the picture book.3 In its first page of text, “5th Inning” (each chapter is named for an inning) speaks of five of the “Greatest Baseball Players in the World: The Negro League All-Stars,” including Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and George “Mule” Suttles. On the page to its left, the chapter’s first image shows Gibson, his uniform’s sleeves rolled up, the muscles on his strong arms visible, hands gripping the bat resting on his shoulder. Beyond making his story stand out, the portrait amplifies the comment that “Josh Gibson was a powerful hitter, but we had other fellows who could hit just as far” (41): this single picture of a strong player stands in for so many others. Nelson’s painting – which also appears on the book’s cover – has Gibson looking directly at the reader, unsmiling, ready to play ball. The look on his face highlights this sentence: “Many of our guys could have rewritten the record books if they had been given the chance to play in the majors” (41). The juxtaposition of those words with his determined expression conveys the sense that those are his thoughts right now, while he stares at us.

Critics would be correct to point out that, at about 500 words per page, We Are the Ship has far more text than an ordinary picture book; at 88 pages (including index), Nelson’s chronicle is much longer than a typical picture book, which runs 64 or fewer pages. However, the 2008 Caldecott winner The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2007) is over 500 pages, and Nelson’s We Are the Ship succeeds because of “the interdependence of pictures and words,” to quote Barbara Bader’s definition of the picture book.3 In its first page of text, “5th Inning” (each chapter is named for an inning) speaks of five of the “Greatest Baseball Players in the World: The Negro League All-Stars,” including Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and George “Mule” Suttles. On the page to its left, the chapter’s first image shows Gibson, his uniform’s sleeves rolled up, the muscles on his strong arms visible, hands gripping the bat resting on his shoulder. Beyond making his story stand out, the portrait amplifies the comment that “Josh Gibson was a powerful hitter, but we had other fellows who could hit just as far” (41): this single picture of a strong player stands in for so many others. Nelson’s painting – which also appears on the book’s cover – has Gibson looking directly at the reader, unsmiling, ready to play ball. The look on his face highlights this sentence: “Many of our guys could have rewritten the record books if they had been given the chance to play in the majors” (41). The juxtaposition of those words with his determined expression conveys the sense that those are his thoughts right now, while he stares at us.

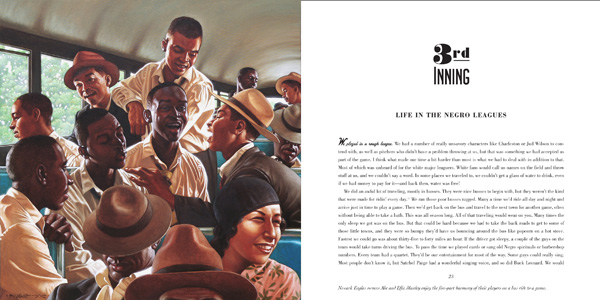

Nelson’s borderless single-page and double-page illustrations immerse the reader in the world of the league. Just after the narrator tells us that the Negro League’s success inspired white owners of independent Negro teams to form a “rival league of their own” (9), we turn the page to find two pages filled with a single magnified ticket for the first Colored World Series, between the Kansas City Monarchs and the Hilldale Club in 1924. Both pages of this spread unfold out, revealing a panoramic view – four pages wide – of both teams and their managers, standing in Kansas City’s Muehlebach Field. The effect is like stepping into a color photograph, even though it’s actually a painting based on a black-and-white photo. Enhancing the vividness of the athletes, Nelson renders them in detail and in color, but leaves the crowds behind them blurrier and in shades of grey. The contrast between the fuzzy background and the crisp, bright foreground makes the teams pop out at the viewer. Though a period photograph would likely have had handwritten names beneath each person, Nelson’s typewritten captions convey an air of historical authenticity. The result makes us feel as if we are both looking at and standing inside a photo from 1924.

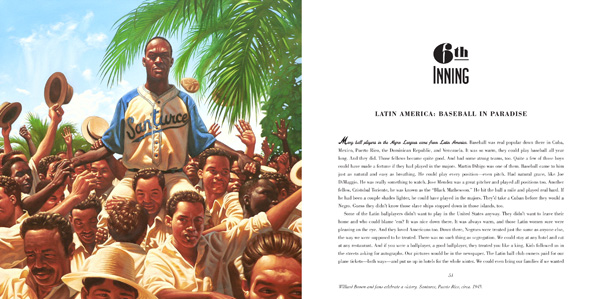

Writing in a conversational tone, Nelson makes history come alive by creating the feeling of an oral interview, as if an old-time Negro league player were talking to us. When discussing the fact that many ballplayers came from Latin America, Nelson’s narrator says of Cristóbal Torriente: “If he had been a couple shades lighter, he could have played in the majors. Major league owners would take a Cuban before they would a Negro. Guess they didn’t know slave ships stopped down in those islands, too” (53). The omission of “of” between “couple” and “shades,” the absence of “I” before “Guess,” and the contraction “didn’t” creates an informal, colloquial feel to the language. In his Author’s Note, Nelson reveals that this was precisely his intent: he read interviews and listened to ex-players tell their stories, and decided that “hearing the story of Negro League baseball directly from those who experienced it firsthand made it more real, more accessible” (80).

The result of eight years’ work, We Are the Ship will appeal to anyone interested in baseball, portraiture, history, the struggle for civil rights, or beautiful picture books. Taking its title from Negro National League founder Rube Foster’s comment that “We are the ship; all else the sea,” Nelson’s book chronicles the rise and demise of the league that began to fade when the Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson in 1947. In so doing, Nelson brings to life the unsung heroes of the sport. As he writes, “We had many Josh Gibsons in the Negro Leagues. We had many Satchel Paiges. But you never heard about them. It’s a shame the world didn’t get to see them play” (51). Thanks to We Are the Ship, the world will now at least get a glimpse.

However, more people would get that glimpse if We Are the Ship had won the Caldecott – because that would ensure its presence in every single public and school library in America.  I realize, of course, that award-winners are the result of a consensus; the prize goes to whichever book more committee members agree on.  And the work that beat Nelson’s, Beth Krommes‘ pictures for Susan Marie Swanson‘s The House in the Night (2008), is definitely good.  The elegant simplicity of the text (inspired by a nursery rhyme) works well with the scratchboard-and-watercolor artwork, itself reminiscent of classic illustrations by, say, Wanda Gág.  I see why the committee chose The House in the Night. I like the book, and enjoy re-reading my copy. But We Are the Ship is more innovative, distinctive, and virtuosic.  In sum, “the most distinguished American picture book for children” of 2008 was and is We Are the Ship.

__________

1. “Welcome to the Caldecott Medal Home Page.” American Library Association. <http://www.pla.org/ala/mgrps/divs/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/caldecottmedal/caldecottmedal.cfm>.

2. “The Coretta Scott King Book Awards for Authors and Illustrators.” Â American Library Association. <http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/rts/emiert/cskbookawards/slction.cfm>.

3. Barbara Bader, American Picturebooks from Noah’s Ark to the Beast Within (New York: Macmillan, 1976), p. 1.

Angela

Eric Carpenter

Philip Nel

Pingback: The Santurce Crabbers: Sixty Seasons of Puerto Rican Winter League Baseball : Team Sport Guide

Marcia ianni

Pingback: The Picture Book Is Dead; Long Live the Picture Book

Beth Krommes

Philip Nel

Philip Nel