I sometimes feel that I should apologize to students who took earlier iterations of my courses. I know more now than I did then, and have crafted a much better syllabus than we used for that earlier class. That said, I also know that in a few years’ time, I will consider my current (new! improved!) syllabi to be embarrassingly inadequate. But, then, the more we learn, the more we are conscious of how much we do not know.

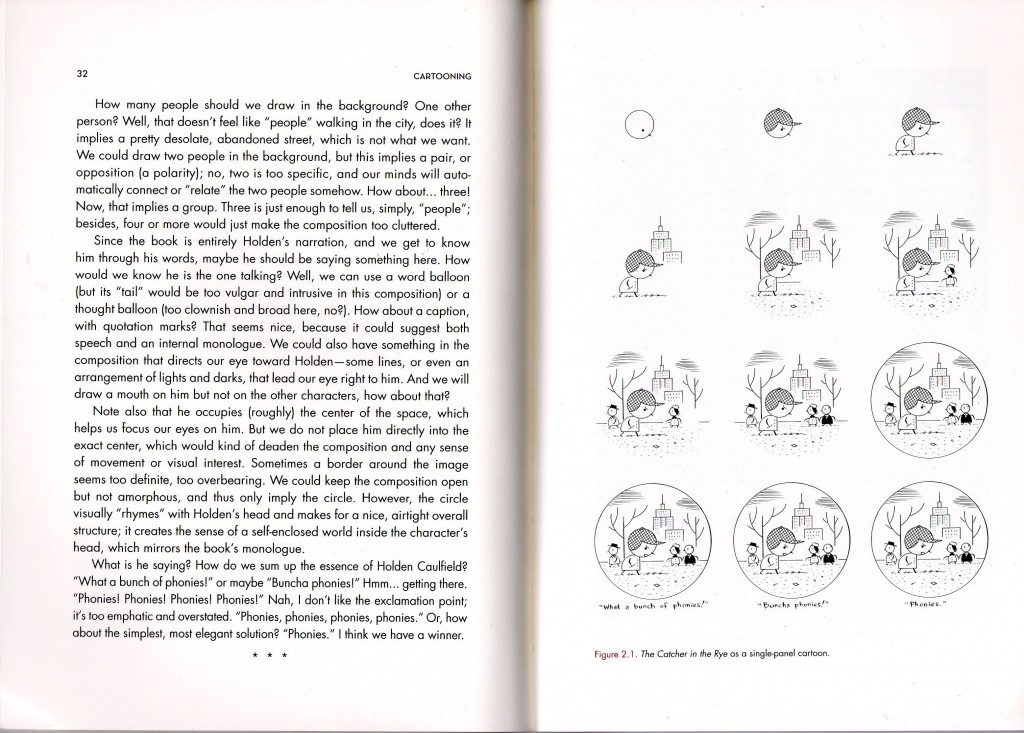

My new “Graphic Novel” course – its third iteration – occasions these reflections. I’m particularly pleased with the paper assignments: Using Ivan Brunetti’s Cartooning Philosophy and Practice (a required text for the first time), I’ve scrapped one large paper for two smaller ones, both of which require (a) creativity and (b) analysis of part a. One of these creative assignments is to render an entire novel as a single-panel cartoon. Yes, this is challenging, but Brunetti walks you through the process, and students can follow his example (click for larger image).

The idea in both this and the other creative assignment is to get the students to think like a comics artist. It is not to create a comics artist. I’m an English professor, and this is neither a creative-writing class nor a studio class & so I do not expect them to create art. In evaluating students’ work, I’m grading their analysis rather than the creative work itself. Why did they make these choices and not different ones?  Do they think their choices worked? What have they learned from the experience? These are the questions their analysis must address.

I want students to see just how difficult and complex the comics form is. With a novel, you have all that is available to a creative writer – diction, tone, metaphor, point of view, and so on. With comics, you have all that is available to a creative writer and to an artist. It’s not only the words that matter; it’s every millimeter of space on the entire page. Students need to think about layout, design, size, shape, space, perspective, and so on. Graphic novels – I’m using the term “comics” and “graphic novel” interchangeably – are far more formally complex than ordinary novels. I hope the creative assignments will help students appreciate the form’s complexity.

I want students to see just how difficult and complex the comics form is. With a novel, you have all that is available to a creative writer – diction, tone, metaphor, point of view, and so on. With comics, you have all that is available to a creative writer and to an artist. It’s not only the words that matter; it’s every millimeter of space on the entire page. Students need to think about layout, design, size, shape, space, perspective, and so on. Graphic novels – I’m using the term “comics” and “graphic novel” interchangeably – are far more formally complex than ordinary novels. I hope the creative assignments will help students appreciate the form’s complexity.

In order to deepen their sense of how comics work, I’m also assigning more critical reading. Scott McCloud’s definition (juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence) – itself a modified version of Will Eisner’s – has become the dominant way of thinking about comics.  And it’s a valuable paradigm. But Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik provide another model, Brunetti yet another, and Robert C. Harvey another still. It’s valuable for students – and all of us – to ponder competing theories of how comics work.

And it’s a valuable paradigm. But Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik provide another model, Brunetti yet another, and Robert C. Harvey another still. It’s valuable for students – and all of us – to ponder competing theories of how comics work.

An ideal course would give equal time to the single-panel comic (which McCloud excludes from his definition), the daily comic strip, the comic book, and the long-form graphic narrative (often called the “graphic novel”). Mine spends most of its time on the longer-form works, but does include more comic strips than it used to – and that’s an improvement. What I really want is a brief anthology of classic comic strips, running from Winsor McCay (Little Nemo in Slumberland) to Richard Thompson (Cul de Sac). The large format of McCay would make his inclusion tricky, but let’s say we just include one McCay and as a fold-out. Then you’d want other greats: George Herriman, Otto Soglow, Frank King, Ernie Bushmiller, Hal Foster, Milt Caniff, Crockett Johnson, Walt Kelly, Charles M. Schulz, G. B. Trudeau, Lynn Johnston, Lynda Barry, Bill Watterson, Aaron McGruder, Richard Thompson. Oh, and I’m sure I’m missing someone. Anyway, one could do a week’s worth of a narrative-driven strip but otherwise restrict the selection to a few Sunday strips per artist, say. This is the anthology I want to assign. Since it doesn’t exist, I furtively copy a very few strips for the course pack or handouts.

It’s all about balancing competing interests. I want different graphic styles, different time periods (my course offers only a glance a medium’s history, alas), different identity categories (race, gender, sexuality, nationality, &c.). On this last point, I’m pleased to be including Ho Che Anderson’s excellent King: A Comics Biography, but sad to have lost Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese and even Neil Gaiman’s Sandman (!). There are texts I feel bad about cutting (Persepolis, which does at least remain on my Lit for Adolescents syllabus), work that I keep meaning to include but don’t (Joe Sacco’s Palestine), and artists I lack the courage to assign in an undergraduate class (I’ve taught the brilliant, powerful, disturbing work of Phoebe Gloeckner in a grad class, but not undergrad). But I like what’s there: Spiegelman’s Maus, Tan’s The Arrival, Barry’s One Hundred Demons, Tezuka’s Buddha (Vol. 1), Bechdel’s Fun Home, Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen, Ware’s brand-new Building Stories (which isn’t out until October), and all the rest. (If you didn’t follow the link to the syllabus in the second paragraph, then click on relevant words in this sentence.)

It’s all about balancing competing interests. I want different graphic styles, different time periods (my course offers only a glance a medium’s history, alas), different identity categories (race, gender, sexuality, nationality, &c.). On this last point, I’m pleased to be including Ho Che Anderson’s excellent King: A Comics Biography, but sad to have lost Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese and even Neil Gaiman’s Sandman (!). There are texts I feel bad about cutting (Persepolis, which does at least remain on my Lit for Adolescents syllabus), work that I keep meaning to include but don’t (Joe Sacco’s Palestine), and artists I lack the courage to assign in an undergraduate class (I’ve taught the brilliant, powerful, disturbing work of Phoebe Gloeckner in a grad class, but not undergrad). But I like what’s there: Spiegelman’s Maus, Tan’s The Arrival, Barry’s One Hundred Demons, Tezuka’s Buddha (Vol. 1), Bechdel’s Fun Home, Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen, Ware’s brand-new Building Stories (which isn’t out until October), and all the rest. (If you didn’t follow the link to the syllabus in the second paragraph, then click on relevant words in this sentence.)

Every syllabus is an impossible puzzle that begets a series of necessary but regrettable compromises. That’s never more true than in Big Broad Course Topics: Children’s Literature, The Novel, the Graphic Novel. These topics are immeasurably huge, and a single semester cannot even approach doing them justice.

But… that’s OK. Each such course provides an introduction to the material, and gives students the skills to seek out more knowledge on their own. And this is the point of college: to prepare students for a lifelong journey of learning. Students should graduate from a university proud of what they’ve learned, but also humbled and inspired by all they’ve yet to learn. College is only the first step.

Taken in that context, I’d say that my syllabi for Fall 2012 – while they could be better, and will be, in future – represent a pretty good first step. (Though, of course, critical comments are always welcome!)

Gwen Tarbox

william nericcio

Charles Hatfield

Charles Hatfield

Pingback: Adolescent Literature: Reading “Wish List” | the dirigible plum