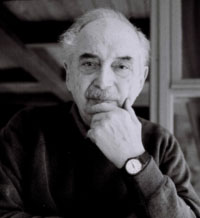

Antonio Frasconi, woodcut artist and children’s-book illustrator, died on January 9th at the age of 93. I heard about it this morning, but I’ve yet to find a full obituary (apart from this brief notice by Joey of Purchase College). So, I’m writing a few words.

He was born in Buenos Aires, to Franco Frasconi (a chef) and the former Armida Carbonia (a restaurateur), both of whom had emigrated from Italy during World War I. Young Antonio grew up in Montevideo, where, by age 12, he had become a printmaker’s apprentice and, by his teens, was seeing his satirical cartoons appear in local newspapers.

In the 1940s, he began working in woodcuts, producing work which won him a scholarship from the Art Students League in New York. To study there, he emigrated to the United States in 1945. By 1948, he had his first exhibit – at the Weyhe Gallery, also in New York.

But the reason I know about him are his beautiful illustrations for children’s books. He married fellow artist Leona Pierce in 1951, and the birth of their first son, Pablo, in 1952, inspired him to create work for young people. As Frasconi noted in a 1994 Horn Book interview, “the happiness he brought, both as an inspiration and as an audience for my work, made me think in terms of using my work as part of his education.” Frasconi observed that, with his accented English, his own reading to Pablo was different than his wife’s reading to Pablo. He went to the library, looking for bilingual books, and, finding none, decided to create his own.

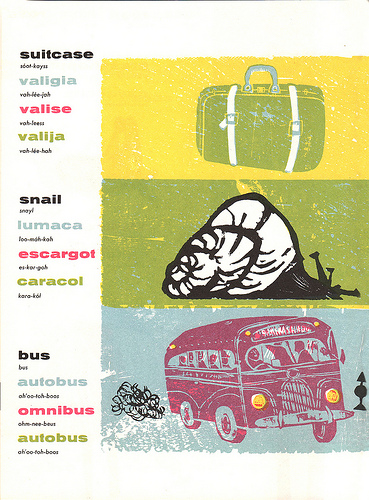

The result was the groundbreaking and beautiful See and Say: A Picturebook in Four Languages (Harcourt, 1955). It presents a series of objects, each named in in English (printed in black), in Italian (blue), French (red), and Spanish (green). Illustrated in bright woodcut prints, the book is a great “first words” book for young children, and language education for any age. Though not the first children’s book Frasconi illustrated, it was the first one he both wrote and illustrated, and I highly recommend it. Used copies are not too hard to find, but this book (attention, New York Review Children’s Collection!) really ought to be brought back into print.

|

The images above come from The Ward-o-Matic‘s post on See and Say. Visit the site to see more.

Back in 2000, I spoke with Mr. Frasconi because he was a very close friend of Crockett Johnson. Both men leaned left, had artistic influences that extended beyond children’s books, and held each other’s work in high regard. Indeed, Antonio’s political leanings inspired him to move – along with his family (Leona, Pablo, and Miguel) – to Village Creek, a planned integrated community that is directly adjacent to Rowayton, Connecticut, where Johnson and his wife Ruth Krauss lived. That was in 1957. The family met Johnson and Krauss soon after moving there, and quickly became friends.

There were regular spaghetti dinners at Ruth and Dave’s house (Crockett Johnson’s real first name was “Dave,” and friends called him “Dave”). Antonio illustrated Ruth’s The Cantilever Rainbow (1965), her greatest avant-garde children’s book. When the Berkeley Free Speech Movement (1964-1965) got television coverage, Dave phoned Antonio so that he could come over and see it (at that time the Frasconis didn’t have a TV). So, the family went over and watched the protests. When Dave started serious painting, the Frasconis were among the first people he showed them to. As Miguel Frasconi recalled, Dave was “so excited,” as he explained to Antonio “the geometric properties of these pictures – like he had discovered something totally new.” At the time, Miguel thought: “this is an adult, and he’s as excited as a little kid.”

There were regular spaghetti dinners at Ruth and Dave’s house (Crockett Johnson’s real first name was “Dave,” and friends called him “Dave”). Antonio illustrated Ruth’s The Cantilever Rainbow (1965), her greatest avant-garde children’s book. When the Berkeley Free Speech Movement (1964-1965) got television coverage, Dave phoned Antonio so that he could come over and see it (at that time the Frasconis didn’t have a TV). So, the family went over and watched the protests. When Dave started serious painting, the Frasconis were among the first people he showed them to. As Miguel Frasconi recalled, Dave was “so excited,” as he explained to Antonio “the geometric properties of these pictures – like he had discovered something totally new.” At the time, Miguel thought: “this is an adult, and he’s as excited as a little kid.”

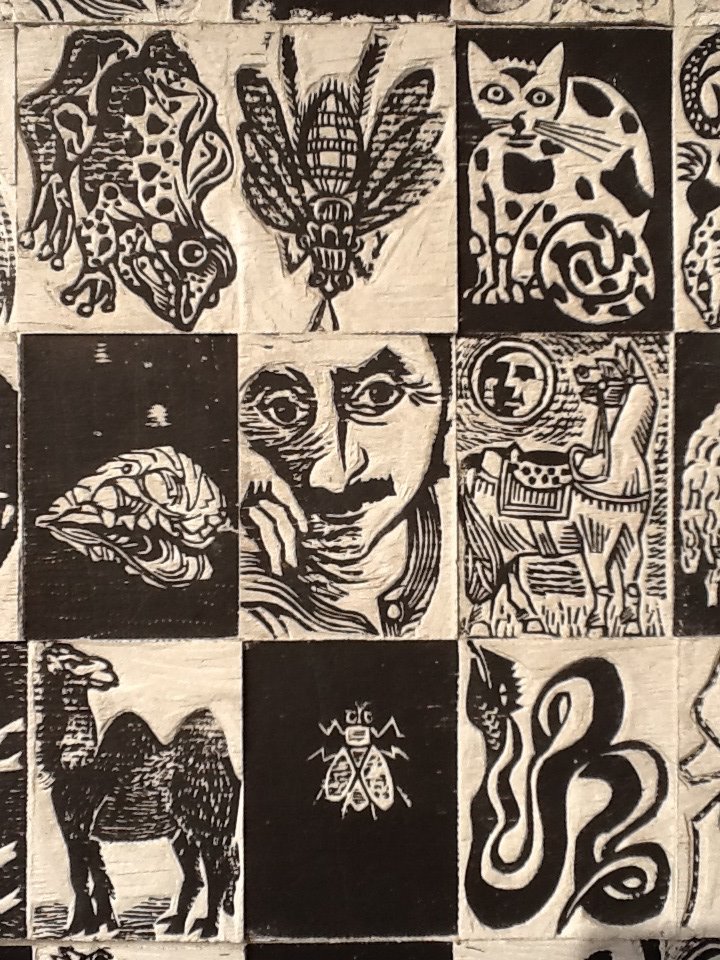

While my own brief acquaintance (one interview, really) with Antonio Frasconi and his family derived from work on my biography of Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss (2012), Frasconi’s work is well worth getting to know in its own right. He illustrated and designed over 100 books, including collections of poetry by Langston Hughes, Walt Whitman, and Pablo Neruda. He created Los Desparecidos (The Disappeared, 1984), a powerful collection of woodcuts that tells the story of those tortured, imprisoned, or killed under the Uruguayan dictatorship. He created art for children’s books. He was a great teacher, artist, and humanitarian.

Thanks for sharing your recollections with me. And rest in peace, Mr. Frasconi.

Works Consulted:

“Antonio Frasconi.” The Annex Galleries. <http://www.annexgalleries.com/artists/biography/739/Frasconi/Antonio>

“Antonio Frasconi.” Contemporary Authors Online. Detroit: Gale, 2003. Literature Resource Center. Web. 13 Jan. 2013.

“Antonio Frasconi (Uruguay).” North Dakota Museum of Art. <http://www.ndmoa.com/Exhibitions/PastEx/Disappeared/Frasconi/index.html>

Goldenberg, Carol. “An interview with Antonio Frasconi.” The Horn Book Magazine Nov.-Dec. 1994: 693+. Literature Resource Center. Web. 13 Jan. 2013.

Nel, Philip. Telephone interview with Antonio Frasconi. 12 Oct. 2000.

—. Telephone interview with Miguel Frasconi. 2 Dec. 2007.

—. Telephone interview with Pablo Frasconi. 28 Nov. 2007.

Sources for images: Facebook post from Miguel Frasconi, Ward-o-Matic blog post on See and Say, and “Artist and Professor Antonio Frasconi, 1919-2013” (at Jane Public Thinking).

DALE FULLER

Philip Nel

Hannah Mae

Pingback: Antonio Frasconi, Woodcut Master

Philip Nel

Carl Reilly

Philip Nel

Pingback: Keeping a Green Tree in your Heart: A Selection of Tree Poetry Books –

THOMAS GENTILLE