For America’s Independence Day, here’s a little-known chapter in the history of American anti-racism. Following the Second World War, progressives founded a dozen planned integrated communities across the country. While working on my biography of Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss, I learned about one of those communities – a section of Norwalk Connecticut directly adjacent to where Johnson and Krauss lived, and where they both had several friends. Its name is Village Creek. It was and is a fully integrated community. Here’s how it began.

For America’s Independence Day, here’s a little-known chapter in the history of American anti-racism. Following the Second World War, progressives founded a dozen planned integrated communities across the country. While working on my biography of Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss, I learned about one of those communities – a section of Norwalk Connecticut directly adjacent to where Johnson and Krauss lived, and where they both had several friends. Its name is Village Creek. It was and is a fully integrated community. Here’s how it began.

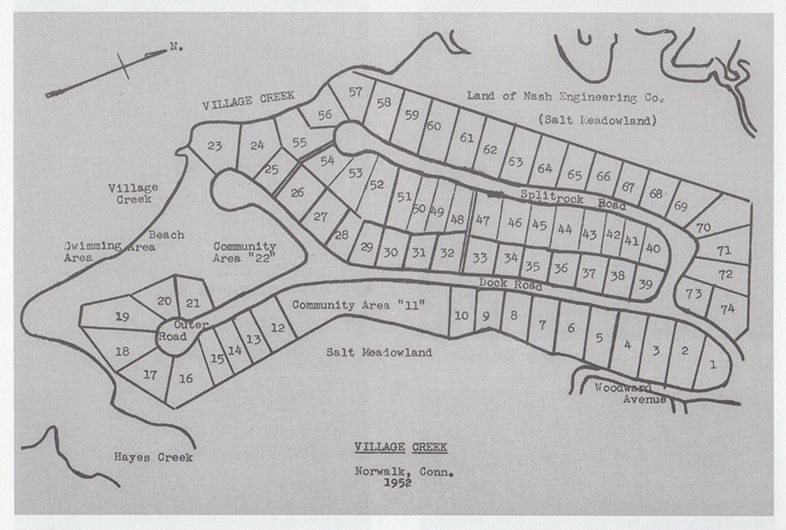

In 1948, city planner Roger Willcox was looking for a home within commuting distance from New York. He and about thirty other people, most of whom were veterans and sailors, wanted waterfront property where they could raise their families and go sailing. As Willcox recalled, when discussing the kind of community they would like to have, they decided that “one of the basic principles” was that there should be “no discrimination because of race, creed or color. The world is made of all colors, creeds, and if we’re going to build a community that we want families to grow up in, and have it recognized in the world, it ought to represent the kinds of people who live in the world.”1 In July of 1949, when they bought the land just across the creek – Village Creek – that would become the Village Creek cooperative neighborhood, they drew up a covenant prohibiting discrimination “on account of race, color, religious creed, age, sex, national origin, ancestry or physical disability.”2

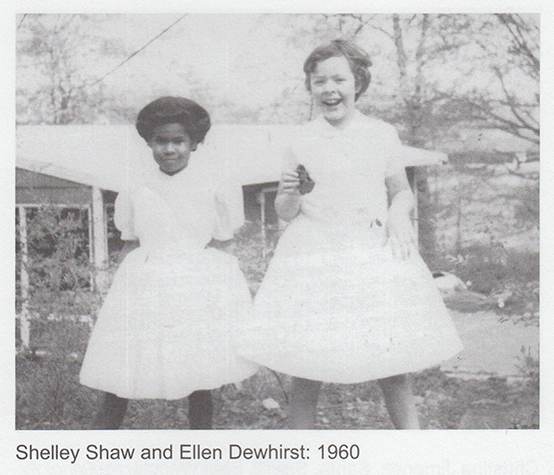

To ensure that it would remain an interracial community, the rules of the Village Creek Home Owners Association specified that Village Creek had to be one third black-owned and two-thirds white owned. To keep the ratio intact, anyone wishing to sell their property had to sell it back to the community. When one of the former residents told me about this ratio, I thought, “Ahh, they’re keeping it two thirds white to placate the whites in the surrounding community.” He said, no, “if we didn’t have this covenant, then if anybody wanted to sell, the real estate agents would immediately go to a black family and say you can move in here because there’s a lot of black people living here. And, of course, then it would start to become a black community. The whites would move out.” And the whole point was to keep it integrated.3

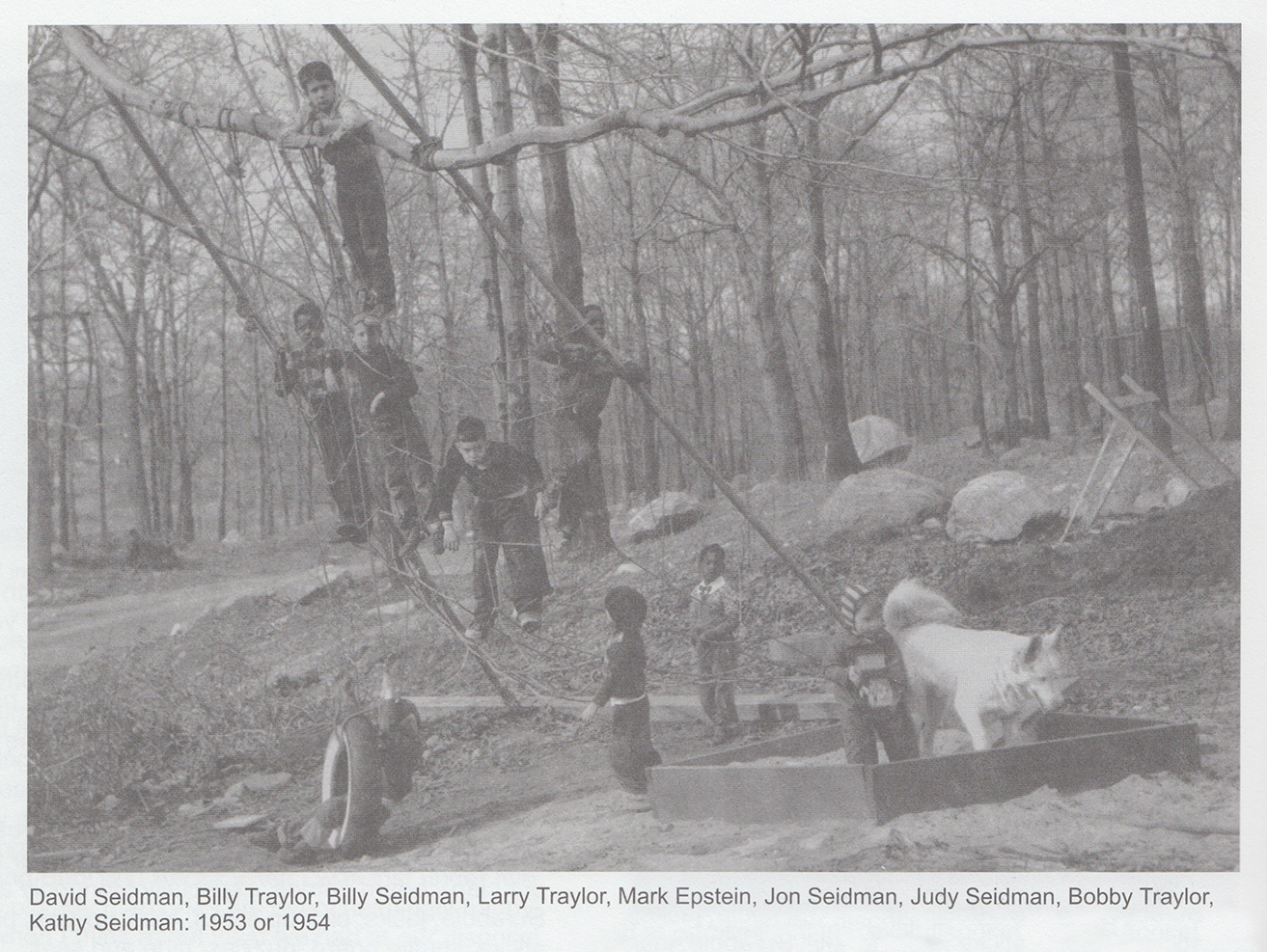

At the time, integrated communities such as Village Creek were virtually unheard-of: this was the first in Connecticut, and, at the same time it was founded, across the United States veterans with similar goals were creating eleven other co-operative communities – some integrated, some simply co-operatives. Although Johnson and Krauss approved of Village Creek (and likely would have bought there if it existed when they moved to Connecticut), many Norwalk residents were suspicious. Detractors called it “Commie Creek” and claimed that the houses’ roofs were designed to guide Soviet bombers to New York City.4 But Village Creekers united against such adversity. When local banks refused to underwrite mortgages on Village Creek homes, Village Creek property owners either built their houses themselves or sought mortgages from New York City banks. When real estate agents would not show Village Creek houses to white families, Village Creekers helped sell houses by word of mouth.5

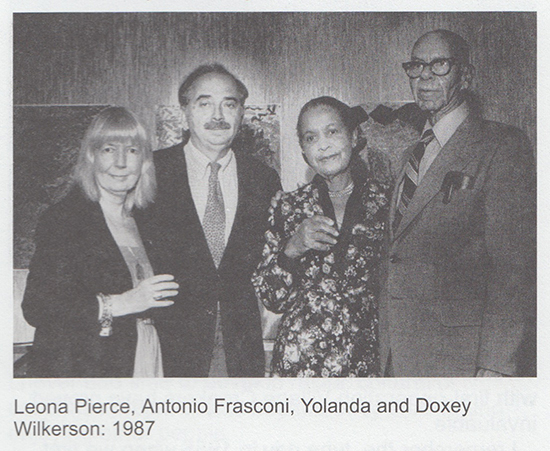

Although it was not “Commie Creek,” Village Creek did attract many progressive residents. Philip Oppenheimer, one of Village Creek’s founding members, met other founding members through their mutual support of Henry Wallace’s 1948 presidential campaign.6 Some other early residents included Doxey Wilkerson, African-American professor of Education and Daily Worker columnist; Frank Donner, civil liberties attorney, AFL-CIO lawyer, and active critic of Anti-Communist witch hunts; and Antonio Frasconi and Leona Pierce, artists who (along with their two children, Pablo and Miguel) would become friends of Johnson’s and Krauss’s.

When Village Creek parents wanted to set up a cooperative nursery school for their children, they asked Norma Simon to help her do it. Norma – whose students inspired Krauss’s A Very Special House – and her husband Ed had moved up to the area in 1952. She had attended the Bank Street School, and by 1952 was teaching at the Thomas School in Rowayton. Norma Simon, with the help of her husband and Village Creek parents, transformed the basement of Martin and Sylvia Garment into the Community Cooperative Nursery School – which would become another place where Ruth Krauss would visit, talk with children, listen to children, make notes, and transform their ideas into children’s books. Founded on Bank Street principles, the Community Cooperative Nursery School was a progressive nursery school; enrolling the children of Village Creek, it had black children, white children, and children of many nationalities. Suspicious of its liberal founders, detractors dubbed it “the Little Red Schoolhouse.”7

In a way, this was hardly surprising, since such detractors also thought that all Village Creekers must be Communists, and even went so far as to say that the modern architecture of Village Creek houses were in fact signals to enemy planes. Norma, whose first children’s book (The Wet World) was published in 1954, soon discovered that her association with “the Little Red Schoolhouse” led to an unofficial blacklist: a PTA would invite her to speak, discover that she was director of the school, and, instead of accusing her directly, would then phone up to say, sorry, but the meeting had been cancelled, no need to come.8

That’s a bit of Village Creek’s early history, most of which had to be cut from my biography, Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature (2012). To the best of my knowledge, no one has written about these post-war utopian experiments. Here’s hoping someone reads this post and writes a full history, or a children’s book. 65 years after its founding, Village Creek is still going strong.

Notes

- Roger Willcox, telephone interview with the author, 26 Sept. 2004.

- Roger Willcox, “President’s Report: Welcome to our 50th Anniversary Celebration.” Village Creek Home Owners Association: 50th Anniversary Celebration (South Norwalk, Conn.: P.M. Ink, 2000), p. 1.

- Martin Garment, telephone interview with the author, 24 Sept. 2002.

- Philip Openheimer, [reminiscence], Village Creek Home Owners Association: 50th Anniversary Celebration. booklet. South Norwalk, Conn.: P.M. Ink, 2000. p. 13.

- Willcox, telephone interview with the author, 26 Sept. 2004.

- Openheimer, [reminiscence], Village Creek Home Owners Association: 50th Anniversary Celebration (South Norwalk, Conn.: P.M. Ink, 2000), p. 13.

- Norma Simon. Telephone interview with the author. 20 June 2002; Martin Garment, telephone interview, 24 Sept. 2002.

- Simon, telephone interview, 20 June 2002.

Further Reading

- Friedan, Betty. “We Built a Community for Our Children.” Redbook Mar. 1955: 42-45, 62-63.

- Prevost, Lisa. “A Planned Community Stays the Course.” New York Times [New York Edition] 26 Sept 2010: RE 8.

- “Village Creek Historic District.” Connecticut Freedom Trail June 2011

Source for photographs

Village Creek Home Owners Association: 50th Anniversary Celebration. booklet. South Norwalk, Conn.: P.M. Ink, 2000

Barbara Morganstern Sammons

Doris Ruth Oppenheimer

Frederick G. Yost

Eva Epple

Sheila Erbter Johnson

frederick yost

Steve Cohen

Pat Haggler

Philip Nel

Catherine Sloane

Tania Theresa Fredericks

Tania Theresa Fredericks

David Greene

David momGreene

Michael Mendershausen

Philip Nel

Jan Kleinbord