When I posted news of my “Censoring Children’s Literature” course last month, several people (well, OK, one person …maybe two) expressed an interest in hearing more about the course. So, given that Banned Books Week is coming up next week, here’s an update. Having lately been examining two versions of Hugh Lofting’s Doctor Dolittle (1920, 1988) and three versions of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964, 1973, 1998), we’ve been addressing this question: Do Bowdlerized texts alter the ideological assumptions of the original? The answer is more complicated than you might think.

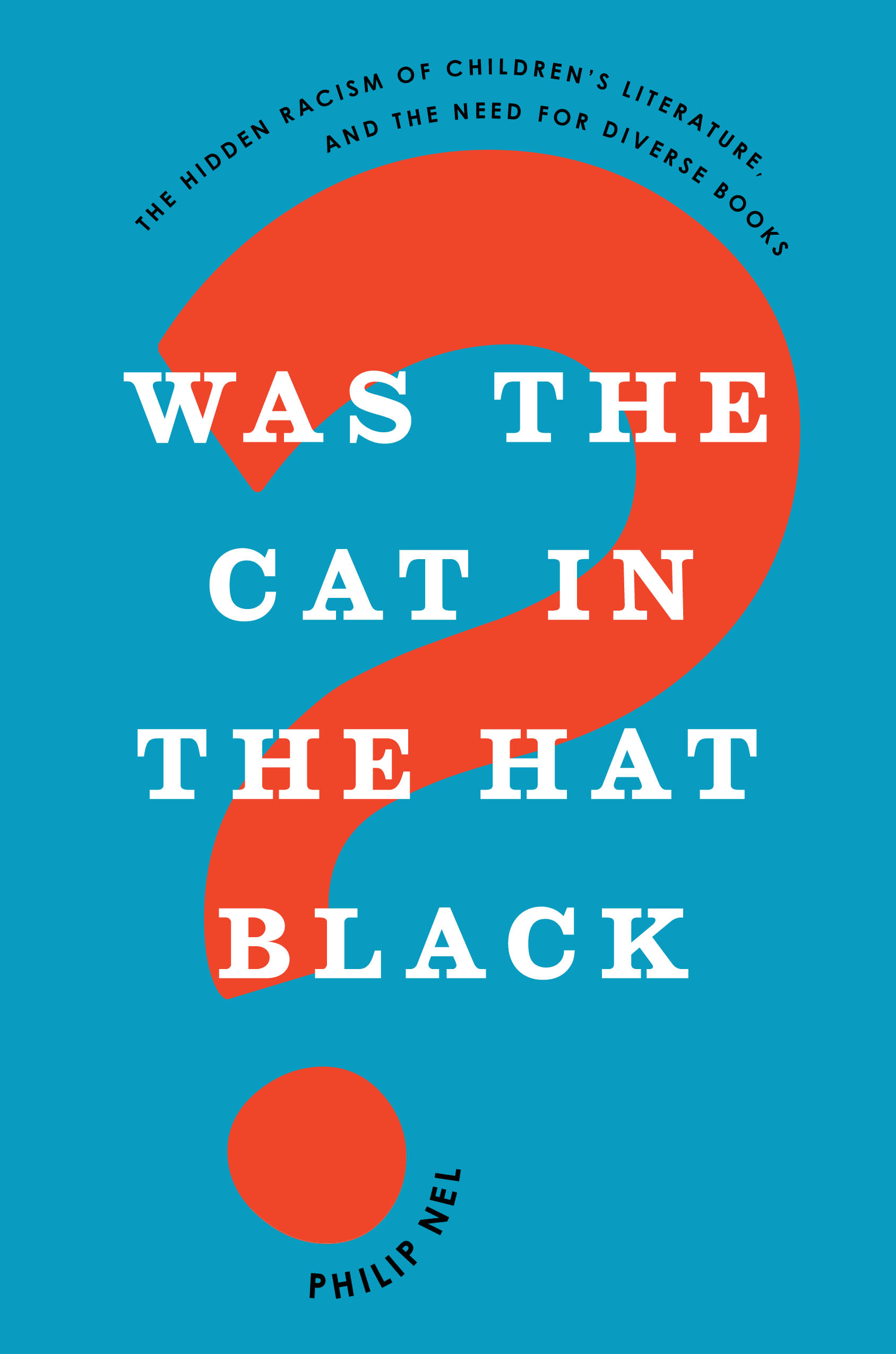

NOTE. Please see my revised, substantially expanded, better inquiry into this subject – Chapter 2 (“How to Read Uncomfortably: Racism, Affect, and Classic Children’s Books”) of Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature and the Need for Diverse Books (Oxford UP, 2017), pp. 67-106.

NOTE. Please see my revised, substantially expanded, better inquiry into this subject – Chapter 2 (“How to Read Uncomfortably: Racism, Affect, and Classic Children’s Books”) of Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature and the Need for Diverse Books (Oxford UP, 2017), pp. 67-106.

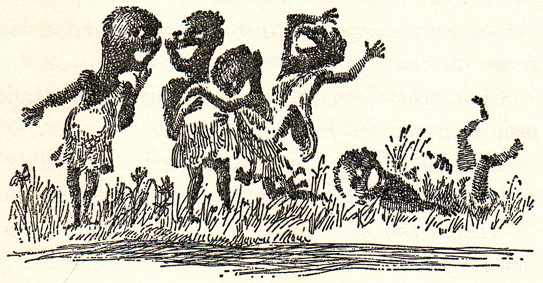

One could make a case for “yes, they do alter the ideological assumptions of the original.” The 1988 edition of Doctor Dolittle removes all references to skin color: “black man” becomes “man,” and “white man” becomes “man” or “foreign man.” Instead of tricking Prince Bumpo by preying on his desire to be white (in the original), Polynesia tricks Prince Bumpo by hypnotizing him (in the current version). In the 1973 edition of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the Oompa-Loompas are no longer African Pygmies – they’re from Loompaland. Illustrator Joseph Schindelman changes their colors from black to white, and current illustrator Quentin Blake keeps them white in his 1998 edition. Inasmuch as Willy Wonka’s workers are human beings imported from another country, the whitened Oompa-Loompas remove the original book’s implication that a person of European descent had enslaved people of African descent, and that the latter group had gladly accepted their new lot as his slaves. Similarly, inasmuch the colonialist impulses of Doctor Dolittle are now no longer so explicitly attached to skin color, the 1988 edition diminishes the overt racism of the original edition. The King of the Jolliginki may still throw childish temper tantrums and Prince Bumpo still may be easily duped, but in the new edition they’re simply color-less victims of Lofting’s satire.

The Oompa-Loompas, as illustrated by Joseph Schindelman, 1964

The Oompa-Loompas, as illustrated by Joseph Schindelman, 1973

The Oompa-Loompas, as illustrated by Quentin Blake, 1998

One could also make a case for “no, they do not alter the ideological assumptions of the original,” claiming that the new versions instead more subtly encode the same racial and colonial messages of the original versions. After all, the Oompa-Loompas still live in “thick jungles infested by the most dangerous beasts in the entire world,” and are still a “tribe” who do not learn English until they come to Britain. Even though the animals are now nonsensical (“hornswogglers and snozzwangers and those terrible wicked whangdoodles”), it’s not unreasonable for a child to assume that a “tribe” living in “thick jungles” are Africans living in Africa. And they still happily acquiesce to being shipped to England “in large packing cases with holes in them,” and find life in a factory preferable to life in their native land. Though I don’t agree with all of Eleanor Cameron’s 1972 critique, the 1973 and 1998 versions of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory do not fundamentally contradict her concerns about “Willy Wonka’s unfeeling attitude toward the Oompa-Loompas, their role as conveniences and devices to be used for Wonka’s purposes, their being brought over from Africa for enforced servitude, and the fact that their situation is all a part of the fun and games.”

Similarly, while the 1988 edition of Doctor Dolittle makes an effort to make race invisible, it does not make the original book’s colonial ideologies vanish. Though now from “the Land of the Europeans” instead of “the Land of the White Men,” Doctor Dolittle is an enlightened white European who goes to civilize the natives. The King of the Jolliginki may now be colorless, but he still lives in a palace “made of mud” in the jungle, and is foolish enough to be duped by a bird (Polynesia). Both he and his men are prone to childlike tantrums, which (even sans color) invokes the stereotype of Africans as childlike. And the monkeys still stand in for indigenous people. They are sick because of lack of proper sanitation (flies infect their food supply), and they have no history: “the monkeys had no history books of their own before Doctor Dolittle came to write them for them, they remember everything that happens by telling stories to their children.” Removing skin color from the text and illustrations does not necessarily remove colonialism. As New York librarian Isabelle Suhl wrote of the Doctor Dolittle series in 1968, “These attitudes permeate the books … and are reflected in the plots and actions of the stories, in the characterizations of both animals and people as well as in the language that the characters use. Editing out a few racial epithets will not, in my view, make the books less chauvinistic.”

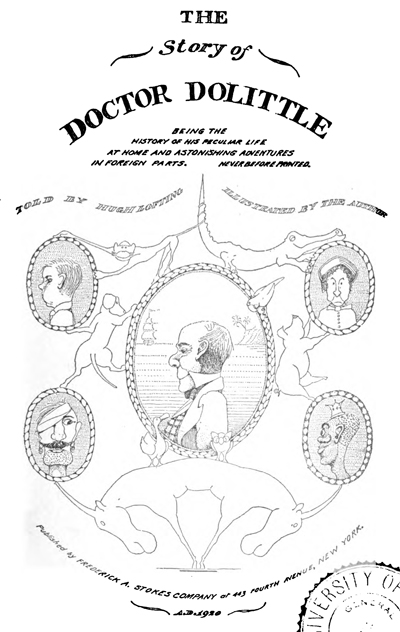

frontispiece, The Story of Doctor Dolittle, illustrated by Hugh Lofting, 1920 |

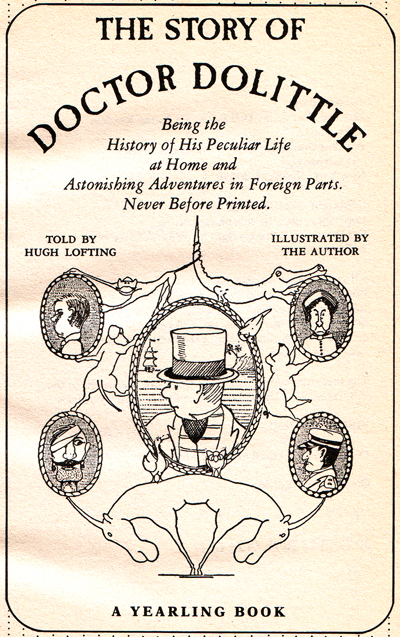

frontispiece, The Story of Doctor Dolittle, illustrated by Hugh Lofting, 1988 |

So, then. What do you do with these books? If you’re persuaded by the idea that de-colorizing the books also removes ideology, then you can with clear conscience read the new versions to young people and encourage young people to read them. After all, Dahl himself revised Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and in so doing replaced Africa with the pleasantly nonsensical Loompaland. And Doctor Dolittle’s kindness towards animals has inspired many advocates of animal rights. The 1988 edition uses the words of one such person, Jane Goodall, as a blurb on the back of the book: “Any child who is not given the opportunity to make the acquaintance of this rotund, kindly, and enthusiastic doctor/naturalist and all of his animal friends will miss out on something important.” Along side of any troubling ideas, the Dolittle books contain much that may delight and instruct.

However, if you’re concerned that the books simply dress up racial and colonial ideologies in different costumes, then you face a choice: (1) Discourage children from reading them, (2) Permit children to read only the Bowdlerized versions, (3) Allow children to read any version, original or Bowdlerized.

(1) Discussing revised editions of her own works, Anne Fine asks, “Which is the real version? Who’s to say? The originals are the ones I would save from a fire. I rather hope the newer versions are the ones my readers would take with them to desert islands.” I think what she means by this is that she hopes people re-read the revised editions, but thinks the originals should be preserved for posterity. In Should We Burn Babar?, Herbert Kohl uses a similar logic: “I wouldn’t ban or burn Babar, or pull it from libraries. But buy it? No. I see no reason to go out of one’s way to make Babar available to children, primarily because I don’t see much critical reading going on in the schools and children don’t need to be propagandized about colonialism, sexism, or racism.” So, then, we might relegate Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Doctor Dolittle – whether original or revised – to the status of cultural artifact, historically significant but no longer read.

One problem with this approach is that it acts as a kind of covert censorship, a blacklist of sorts. It says: “oh, no, we’re not banning the book. We’re just not inviting it.” So, if you’re of a libertarian mindset, this response will not suffice.

(2) What about allowing children to read only the Bowdlerized versions, then? That might (in some measure) appease the person of libertarian leanings who nonetheless does not wish to collude in the replication of harmful ideologies. Yes, it might… if you believe that the Bowdlerized versions do – as Lori Mack, editor of the 1988 version of Doctor Dolittle, said of that volume – “preserve Hugh Lofting’s style and spirit” but without “the offensive caricature.” However, if you’re a literary purist who believes in granting access to the original work or if you worry that these versions offer only a more subtle, insidious kind of propagandizing, then this approach will fail.

But will it? Books containing stereotypes (whether re-costumed or not) invite children to participate in that way of thinking, but children do not have to accept the invitation. They may resist. If a book’s presentation of people of color does not conform to other images of people of color, then a child may dismiss the book as anomalous. As an outlier, it perhaps does not unconsciously shape their perceptions.

(3) If you believe in the child’s potential to resist, then you might argue for granting access to the original work on the grounds that the egregiousness of the original’s stereotypes will serve as a kind of “warning flag.” In other words, one might argue that blunt offensiveness is less harmful than a subtler delivery of prejudices because the reader is more likely to reject the former. We can read a book and disagree with the book; encountering a book with racist imagery might be more likely to provoke our censure. Encountering a book in which that imagery has been cleaned up (even while leaving other underlying assumptions intact) might be less likely to provoke our censure. In sum, we could make the case that unvarnished prejudice serves as a better teaching tool.

One problem of this approach, however, is the disproportional burden it places on members of the stereotyped group. The white child (for example) who encounters Prince Bumpo or an Oompa-Loompa has the unearned privilege of not seeing people of her or his ethnicity being stereotyped. The African-American child (for example) does not have that privilege. This is not to say that prejudice lacks any ill consequences for the dominant group – a white child learning that he or she is more important, more central, can teach that child that dominating children (or adults) of color is acceptable behavior. Rather, this is to say that prejudice harms different groups in different ways.

What, then, is the solution? I’d be the first to acknowledge that there is no ideal solution. One could argue, for instance, that a “colorless” Doctor Dolittle rightly highlights the fact that race is a fiction: black, white, beige, yellow, etc. are pure fantasy. We’re all members of the human race. On the other hand, one could counter that claim by noting that while race may be imaginary, people act on racial distinctions as if they were real: denying the social fact of race is a form of lying.

As an educator, I’m inclined to fall back on the (albeit imperfect) solution of reading troubling texts with young people, and talking with them about what they encounter. As Herb Kohl writes, “It is not developmentally inevitable that children will learn how to evaluate with sensitivity and intelligence what the adult world presents them. It is our responsibility, as critical and sensitive adults, to nurture the development of this sensibility in our children.” Further, he notes, critical reading can be a source of both pleasure and power: “children quickly come to understand that critical sensibility strengthens them. It allows them to stand their ground …. It is a source of pleasure of well – of the joy that comes from feeling that one is living according to conviction and understanding.”

As a negative state, innocence cannot be sustained indefinitely. As they grow up, children will gain experience and knowledge. Some of those experiences will hurt; some of that knowledge will make them sad. If we exclude troubling works from the discussion, then children are more likely to face sadness and pain on their own. It is, I think, better that we give them the tools with which to face prejudice-bearing literature. In doing so, we can help them learn to cope with a world that can be neither just nor fair. With this knowledge, perhaps we may also give them a source of power.

Pingback: Should we burn Babar? | CMIS Evaluation Fiction Focus

Libby

Philip Nel

Monica Edinger

Pingback: What to Do About Classical Children’s Books that are Racist? « educating alice

Pingback: Monica Edinger: What to do about Classical Children’s Books that are Racist? | What's hot right now....

Debbie Reese

Debbie Reese

Mia Olufemi

Libby

Joseph T. Thomas, Jr.

Philip Nel

Joseph T. Thomas, Jr.

Debbie Reese

hope

Philip Nel

Beth Kakuma-Depew

Pingback: Censoring Children’s Books « The Catablogger

Man of la Book

Zhazhmali Stanportafort

Amanda

Pingback: The Great Geek Manual » Geek Media Round-Up: September 21, 2010

Jill Bernstein

Jill Bernstein

the.effing.librarian

Philip Nel

Sayantani DasGupta

Mark

Amy Bennett-Zendzian

anonymous

Marijane White

gwen

Uly

JustD

gwen

Pingback: Weekly links | CMIS Evaluation Fiction Focus

QueenLyzard

Pingback: Fusenews: The broken motel sign adds a nice touch too « A Fuse #8 Production

Pingback: Useful sites (weekly) « Rhondda’s Reflections – wandering around the Web

Shannon

Miss Lynx

Mary Galbraith

Mary Galbraith

Philip Nel

Mary Galbraith

Pingback: Banned Books Week : Embracing Education

Pingback: The Scop: The Website of Jonathan Auxier

Pingback: Paul's Thing » Banned Books Week & Book Review

David

Pingback: Other Places Talking About Roald Dahl Saying Mean Things « Roald Dahl Racism

Pingback: Should We Ban “Little House” for Racism? | Adios Barbie

Mary

BCruz

Ji McArthur

Pingback: Detour - Shelf Directed

Someone

Someone

Pingback: Students at Binghamton: Sick and Tired of being Sick and Tired! | NZINGA

MaryAnn Ruegger

Pingback: Une nouvelle édition de Huckleberry Finn édulcorée | The Buried Talent

Pingback: The Tom and Jerry racism warning is a reminder about diversity in modern storytelling

Pingback: Try, try again? Revising Children’s Literature for Inclusion | theracetoread

Pingback: READING TO THE MAX PRINTABLE | Tips of a Camp Counselor

Pingback: was the cat in the hat black? review – what the log had to say

mark taha

Sally

Kate

Mike

Mike

Pingback: MÄ«li savu tuvÄko jeb Ko darÄ«sim ar neÄ“rtajiem vÄrdiem literatÅ«rÄ? | punctum

Pingback: Doctor Dolittle: Charming Or Uncomfortable? | Befferkins, the Random