As American fast food workers strike for a living wage, it’s worth remembering that this struggle has a long history. It’s also worth teaching some of this history to children, so that they can learn about collective action, and fighting back against the powerful.  Julia Mickenberg and I collect some of these stories in the “Work” and “Organize” sections of our anthology, Tales for Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children’s Literature (2007), but there are many more such stories out there.  Michelle Markel and Melissa Sweet‘s Brave Girl: Clara and the Shirtwaist Makers’ Strike of 1909 (2013) is one of those.

A picture book published earlier this year, Brave Girl tells of newly arrived immigrant Clara Lemlich, who – as Markel’s text tells us – “knows in her bones what is right and what is wrong.”  When “no one will hire Clara’s father,” she gets a job as a garment worker to support her family, and quickly discovers what is wrong: companies hire immigrant girls to make clothing, paying them just a few dollars a month. Markel effectively dramatizes the cruel working conditions: “locked up in a factory,” she and the other young women are “stitching collars, sleeves, and cuffs as fast as they can. ‘Hurry up, hurry up,’ the bosses yell. The sunless room is stuffy from all the bodies crammed inside. There are two filthy toilets, on sink and three towels for three hundred girls to share.”  They’re also fined a half day’s pay for being a few minutes late, fined if they prick a finger and bleed on the cloth, and fired if that happens twice.  With just a few vivid details, Markel’s words and Sweet’s images gives us a sense of the oppressive, stifling working conditions.

A picture book published earlier this year, Brave Girl tells of newly arrived immigrant Clara Lemlich, who – as Markel’s text tells us – “knows in her bones what is right and what is wrong.”  When “no one will hire Clara’s father,” she gets a job as a garment worker to support her family, and quickly discovers what is wrong: companies hire immigrant girls to make clothing, paying them just a few dollars a month. Markel effectively dramatizes the cruel working conditions: “locked up in a factory,” she and the other young women are “stitching collars, sleeves, and cuffs as fast as they can. ‘Hurry up, hurry up,’ the bosses yell. The sunless room is stuffy from all the bodies crammed inside. There are two filthy toilets, on sink and three towels for three hundred girls to share.”  They’re also fined a half day’s pay for being a few minutes late, fined if they prick a finger and bleed on the cloth, and fired if that happens twice.  With just a few vivid details, Markel’s words and Sweet’s images gives us a sense of the oppressive, stifling working conditions.

“But Clara is uncrushable,” Markel tells us. Â That’s one of the key messages of the book. Â Clara is a fighter. Â Hungry and exhausted, she goes to the library to learn, getting by on a few hours of sleep a night. When the men don’t think that the women are tough enough to join a union and strike, Clara (the book always calls her by her first name, perhaps to create greater intimacy between character and reader) leads them out on strike. Â Police arrest her, hired thugs beat her: “They break six of her ribs, but they can’t break her spirit. It’s shatterproof.”

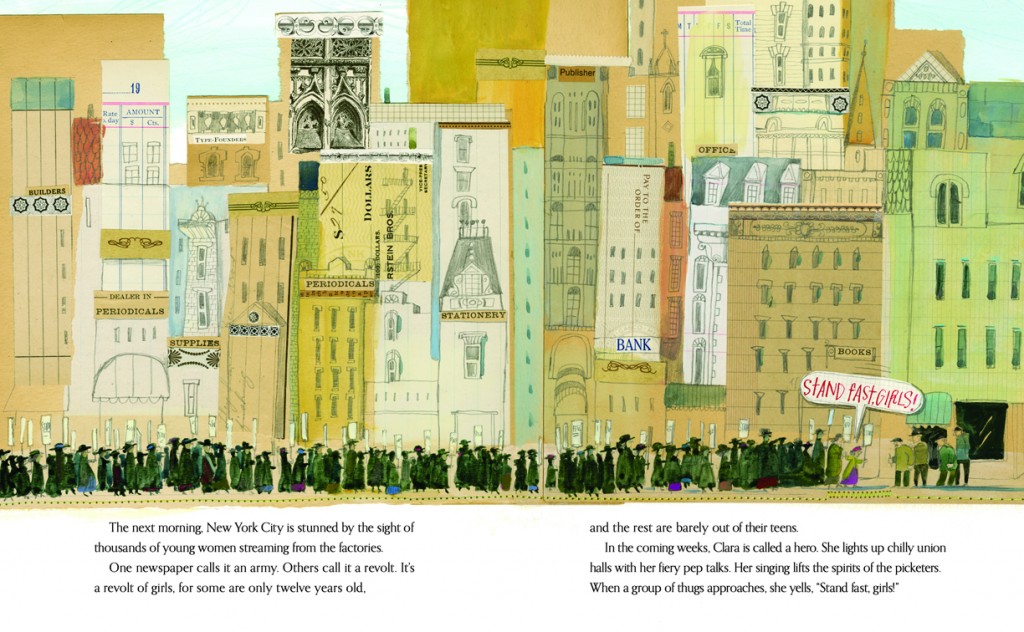

Another key message is that collective action creates change. At the book’s climax, Clara calls for a general strike, and in the winter of 1909 leads 20,000 garment workers out on a general strike.

The third important lesson young readers will take away here is that progress is hard-won and imperfect. The garment workers win the right to unionize, gaining better pay and a shorter workweek. However, getting there required them to walk the picket lines in the dead of winter, where they faced police brutality, backed by a legal system indifferent to their cause. In the end, though 339 dress manufacturers agreed to unions, the Triangle Waist Factory – where Clara herself worked – did not. Indeed, two years after this strike, the Triangle Waist Factory’s business practices (such as locking the workers in) killed 146 when a fire broke out in the building.

Amplified by Melissa Sweet’s watercolors and fabric-themed collages, Markel offers a history that should inspire a new generation of activists.  So, as you celebrate Labor Day today, remember the unions that made it possible.

Related posts on this blog:

- The Company Owns the Tools (3 Sept. 2012)

- This One’s for the Workers: Labor Songs, 1929-2010Â (3 Sept. 2011)

- Philip Levine’s “What Work Is” (4 Sept. 2011)

- Little Rebels, Little Conservatives, and Occupy Wall Street (19 Oct. 2011)

- Radical Children’s Literature Now! (article)Â (19 Nov. 2011)

- Radical Children’s Literature Now! (video)Â (30 July 2011)

- Radical Children’s Literature Now! (handout)Â (25 Jun. 2011)