Gene Marks’ instantly infamous “If I Were a Poor Black Kid” column (Forbes, 12 Dec. 2011) is a classic example of how privilege remains invisible to the privileged. Though he acknowledges that he is “a middle aged white guy who comes from a middle class white background” and so “life was easier for” him, the rest of his column betrays too little of the awareness expressed by those early sentences. For instance, “If I was a poor black kid I’d use the free technology available to help me study” assumes that the kid in question would have access to this technology. Even a claim as benign as “If you do poorly in school, particularly in a lousy school, you’re severely limiting the limited opportunities you have” overlooks the fact that it takes an unusual student to rise above the limitations of a “lousy school.” Sure, there are students who do this, but they’re the exception, not the rule.

Mr. Marks assumes that opportunity is equally distributed. While we might admire the personal optimism conveyed by a claim like “I believe that everyone in this country has a chance to succeed,” the article does not sufficiently acknowledge that some people – those with access to better schools, those who do not go to bed hungry, those with health care – have a much, much better chance of success.

I owe my own success to precisely that sort of privilege. Don’t misunderstand: I have worked hard, and I continue to work hard. But my success in life derives not just from my work ethic. It also comes from unearned privilege.

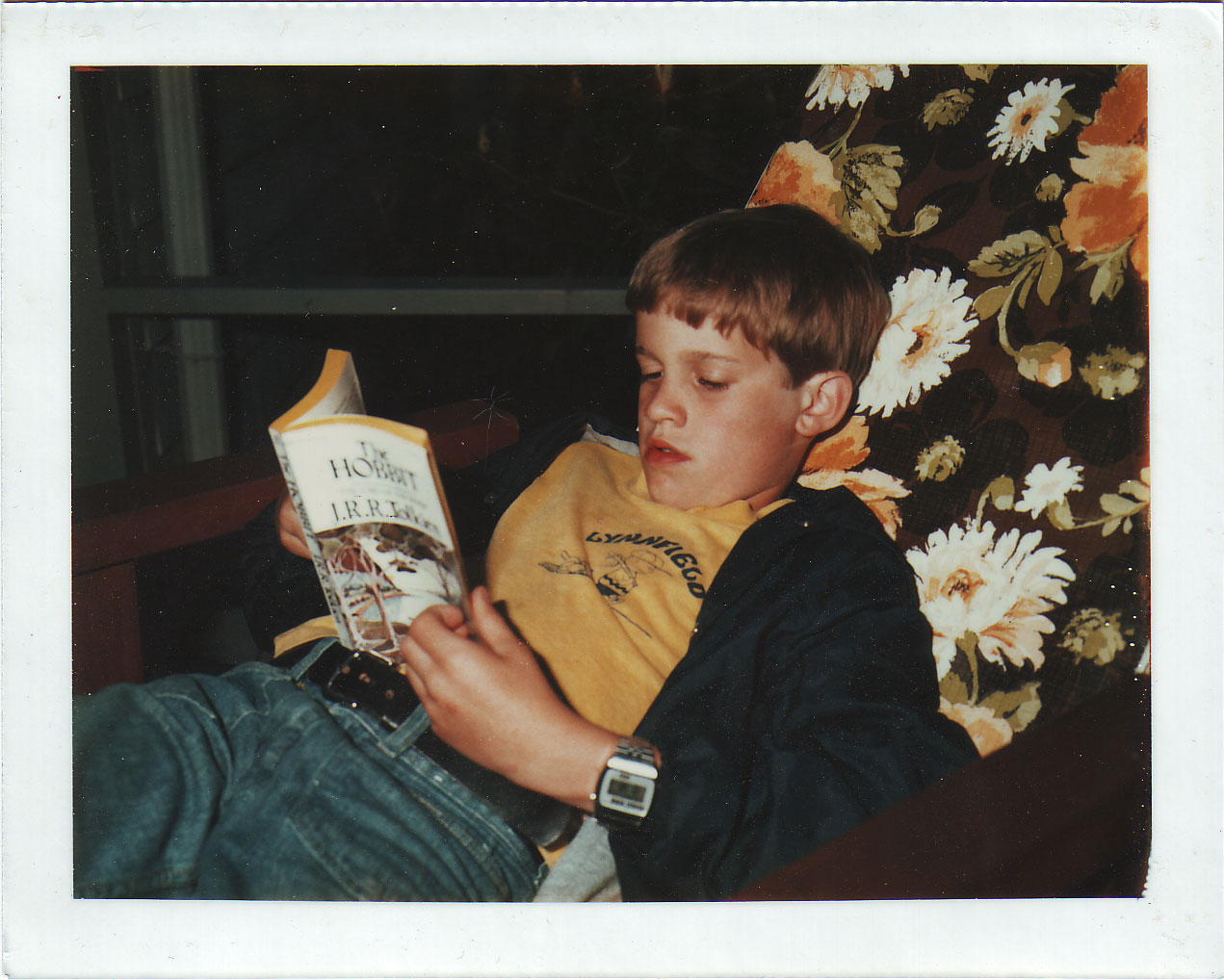

If I had stayed in public school, I’m not sure that I would have gone to college at all. On my first day of first grade, the teacher asked which of us could read. I was among those few who raised my hand – I’d been reading since I was 3 years old. She gave us literate students a book to read. I finished it first, and raised my hand. “I’ve finished,” I said. Her response: “Read it again.” I began to read it again. On my first day of school and subsequent ones, I learned that school was boring.

The result was that, though I still read for pleasure, I became a terrible student. I’d finish the worksheet first, and then devote my free time to amusing my classmates. I paid attention only when it suited me, trusting that I’d be able to master the material on my own. For a few years, this approach worked well. However, by the time I reached sixth and seventh grade, it was no longer working. My grades were slipping, and I began to slip behind.

And here’s where that unearned privilege saved me.

Just before I entered eighth grade, my mother got a job teaching at private schools – first, Shore Country Day School (in Beverly, Mass.), and second, Choate Rosemary Hall (in Wallingford, Conn.). Her employment allowed my sister and me to attend both schools for free. That’s right: in addition to receiving a salary (and on-campus housing in the case of Choate), her labor enabled her offspring to attend gratis. Had she lacked a college degree, had she lacked experience teaching and working with computers, I would not have had that opportunity.

She’s also a great example of how privilege – or its lack – gets compounded over time. She worked hard, overcoming both the diminished expectations accorded her gender, and discrimination from male bosses. But she also benefited from privilege. As a white South African, she had access to educational opportunities that black South Africans did not. I can say with certainty that if my mother were from the same country but of a different race, I would not be where I am today. That’s unearned privilege.

Attending private schools made all the difference for me. Although I had peers in public school (a perfectly adequate public school) who did well and went on to college, I too easily succumbed to the prevailing attitude (among the students) that one should do as little as possible. In private school, however, the prevailing attitude was that we all needed to work hard. The work was challenging, and we had to rise to our teachers’ expectations.

That was just the nudge I needed. I didn’t become an “A” student overnight. Indeed, I had to do an extra year at Choate to pass the language requirement (there was no way I was going to make it through third-year Russian), and to get my grades up enough to get into college. Aided by a semester abroad (in Valladolid, Spain), I did three years of Spanish in two years, improved my grades, and got accepted at a couple of good colleges.

At the University of Rochester, I became a model student, and graduated summa cum laude with a B.A. in both English and Psychology. But, here, too, privilege came to my aid. Having that excellent private-school education meant that I knew how to study. During my freshman year, many of my public-school friends were shocked by the amount of work. I wasn’t. The work may have been harder, but I knew what I had to do.

In calling attention to the role privilege has played in my own success, I do not mean to dismiss the role of a solid work ethic. Mr. Marks is correct to emphasize the importance of hard work. For most of college, I worked two jobs – one via Work/Study, and one as a Resident Advisor (which paid for room and half of board). I say “most” because I became an R.A. my second year; indeed, I was one of two sophomore R.A.s that year. (The others were all juniors and seniors.) In addition to those jobs, I studied hard, spending long hours in the library. I carried those work habits on to graduate school and into my career as an English professor.

However, I must point out that I was not working, say, 30-hour weeks in addition to doing schoolwork. The hours of the R.A. job varied, and the Work/Study job was, to the best of my recollection, about 8 hours a week, give or take. I have students now who work full-time, are the sole caregiver for their children, and are pursuing a B.A. That’s a much steeper hill to climb.

The problem in this country is not laziness. The problem is unacknowledged, unearned privilege. It’s not that people lack industry; they lack opportunity. But the privileged – unconscious of the degree to which their own advantage has aided them – fail to see this, and so write well-intentioned, naïve articles like “If I Were a Poor Black Kid.” Mr. Marks means well, but his prescription for success would not have helped me. And I was a middle-class white kid.

Lia

Joyce

Philip Nel

Sarah

Sarah

tracy tucker

Claudia Pearson

Laura Atkins

Sarah Park

Philip Nel

Robin Bernstein

pete zimm