There are a lot of modernist children’s books, and a fair few directly influenced by the historical avant-garde – and, yes, I am sharing images, below.  I learned about these books (and a great deal more) last week at Children’s Literature and the European Avant-Garde, a conference at Linköpings University, in Norrköping, Sweden.  You would think that the author of a book with two chapters on the intersection between the avant-garde and children’s literature might be better acquainted with this body of work.  But I wasn’t.  As I listened to the international group of scholars speak, I often found myself thinking: Wow! Why didn’t I know this artist’s work?

- One answer was well, Phil, because you’re an American, and so unfamiliar with the Icelandic avant-garde or Hungarian modernism.

- But another, and equally important answer, was that this is the nature of specialized research: people uncover material that others do not, hidden in archives, long forgotten, … or from another field and never yet considered in this context. Â This is one reason we go to conferences.

- Finally, there is very little written on children’s literature and the avant-garde. Â It’s safe to say that this conference gathered together the largest group of people investigating this subject.

For your enjoyment, here is some of the art. Â Following that, brief reflections on the conference itself.

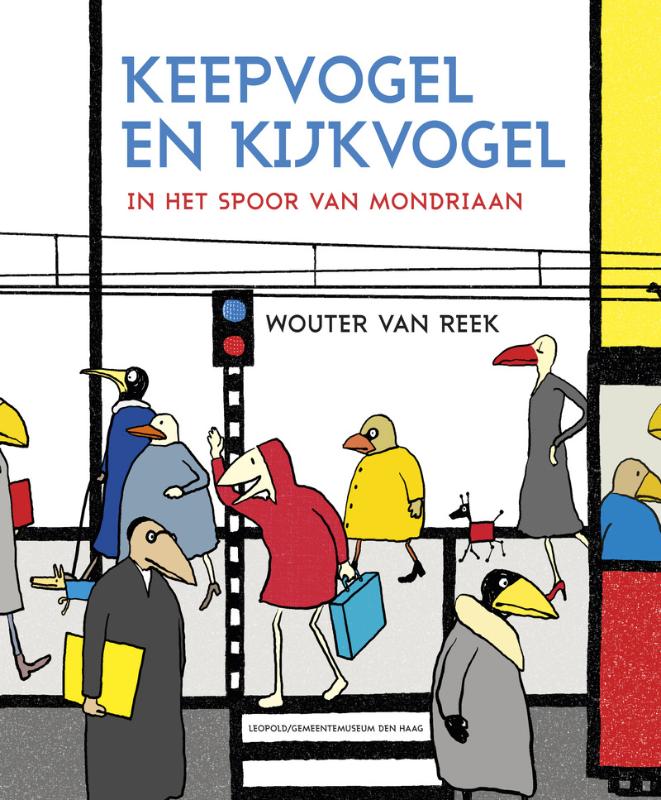

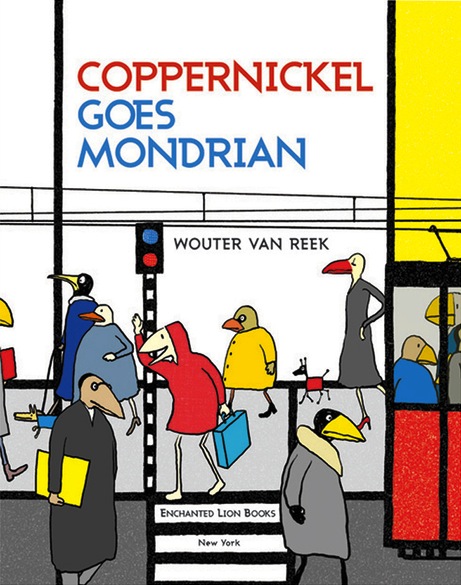

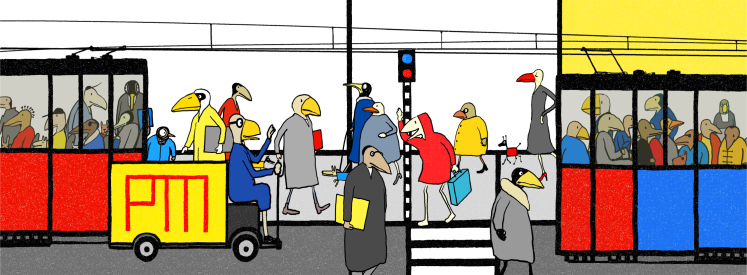

Wouter van Reek

Wouter van Reek’s Keepvogel en Kijkvogel: In Het Spoor Van Mondriaan (2011) – also introduced to us by Saskia de Bodt – has also been published in English as Coppernickel Goes Mondrian (2012).  This is one of many books I’ve added to my “to buy” list.

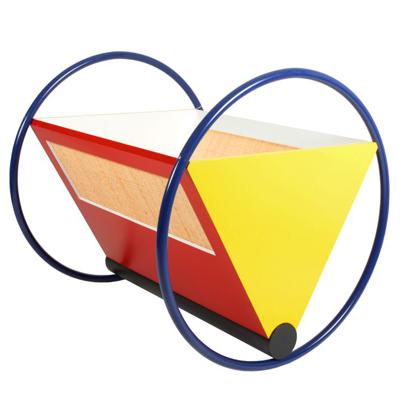

Bauhaus toys!

Michael Siebenbrodt, of the Bauhaus Museum Weimar, showed us (photos of) lots of Bauhaus toys and children’s furniture, such as Peter Keler’s Wiege (1922), a cradle – which, he told us, is weighted at the bottom so that it won’t roll all the way over.

Lyonel Feninger – modernist painter and creator of the Kin-der-Kids comic (1906) – created many toys, mostly (as I recall) for his kids or friends.

Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack’s top (designed in the 1920s) is still in production. Â It’s available from the Naef Store. Â That’s a link to the US version of the store, in the previous sentence: for other locations, try Naef’s main website.

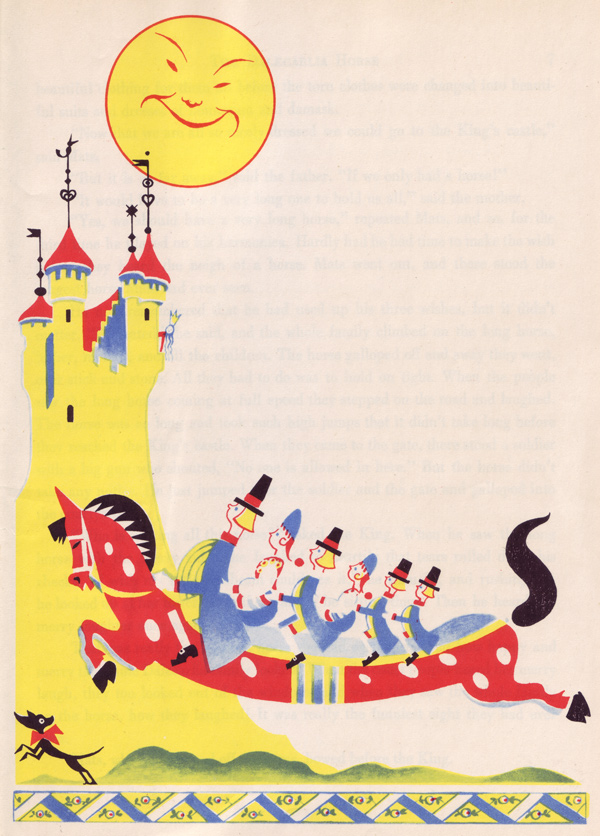

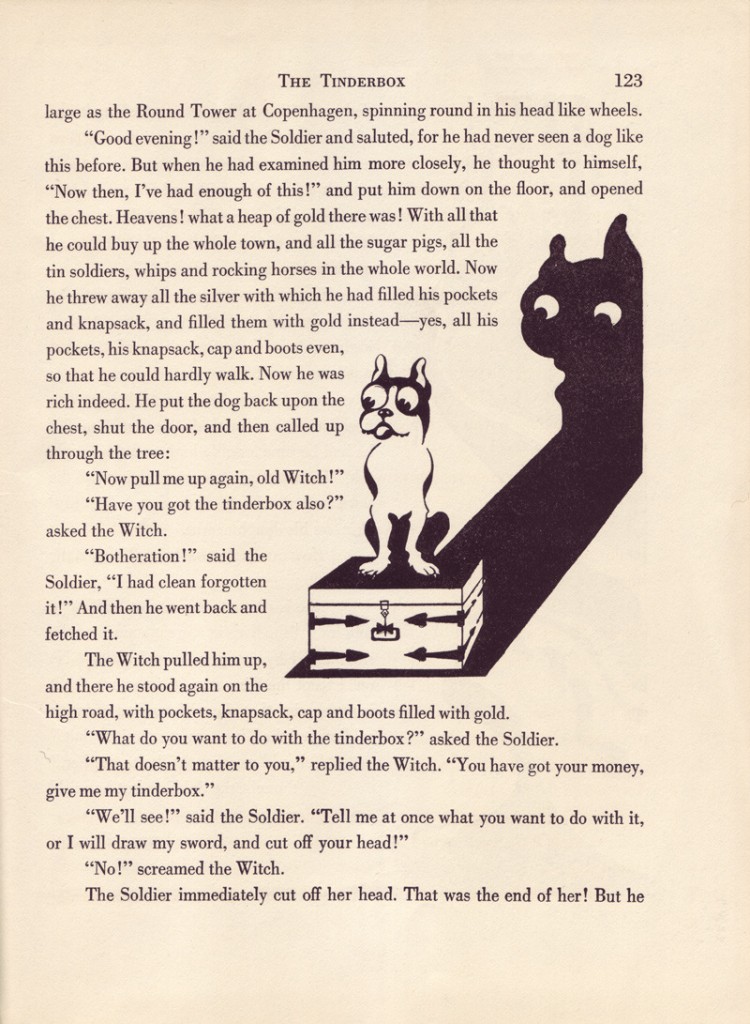

Einar Nerman

Would someone please reissue Einar Nerman’s children’s books?  As Elina Druker told us, Nerman (1888-1983) was a Swedish caricaturist strongly influenced by Art Nouveau.  His picture books are largely unknown today, but they look fantastic.  There’s the beautiful Crow’s Dream (1911), in which animals take over and rule a city – a satirical commentary on our treatment of animals and of each other.  I can’t find images of that on-line, but the great illustration blog 50 Watts has images from Fairy Tales from the North (1946), a few of which I’ll include below.

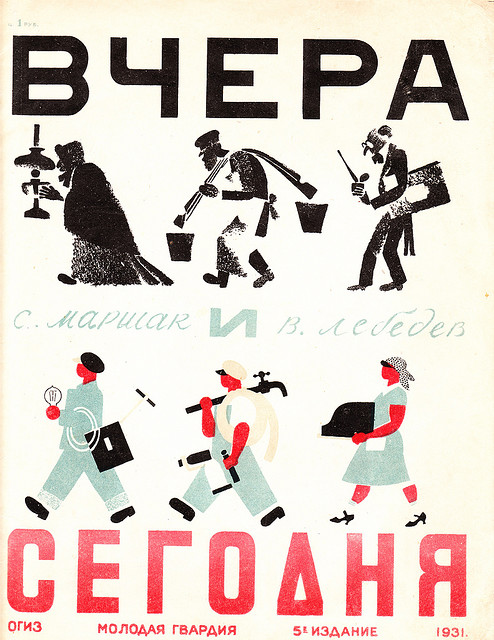

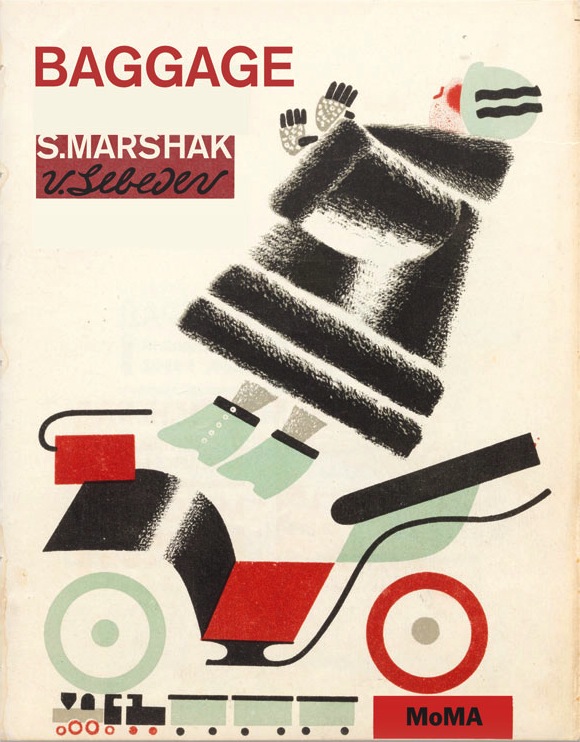

Samuil Marshak and Vladimir Lebedev

Because I was moderating this session, I failed to take many notes on Sara Pankenier Weld‘s insights into poet Marshak and artist Lebedev.  I can tell you that the above title, in English, is Yesterday and Today.  Also worth noting: MoMA has just published an English-language edition of Marshak and Lebedev’s Baggage (1926).

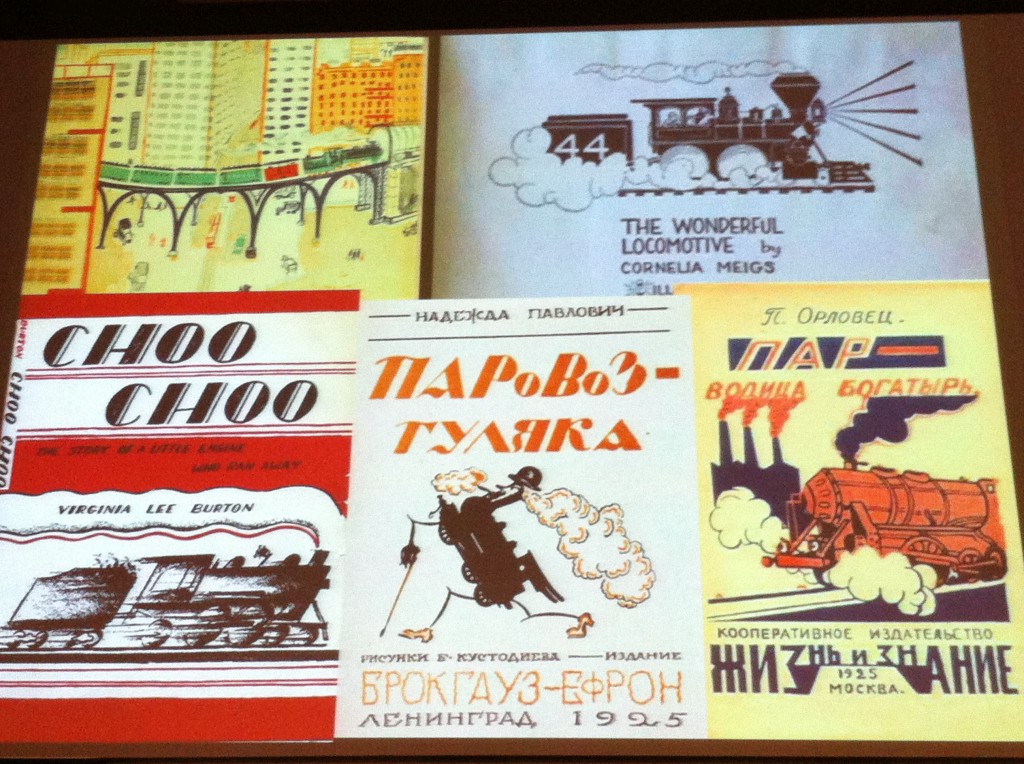

During this same session, Evgeny Steiner juxtaposed US and Soviet books that seemed to mirror each other.

As I said above, my moderating prevented me from getting many notes taken. Â But, here (above) is one slide, at least!

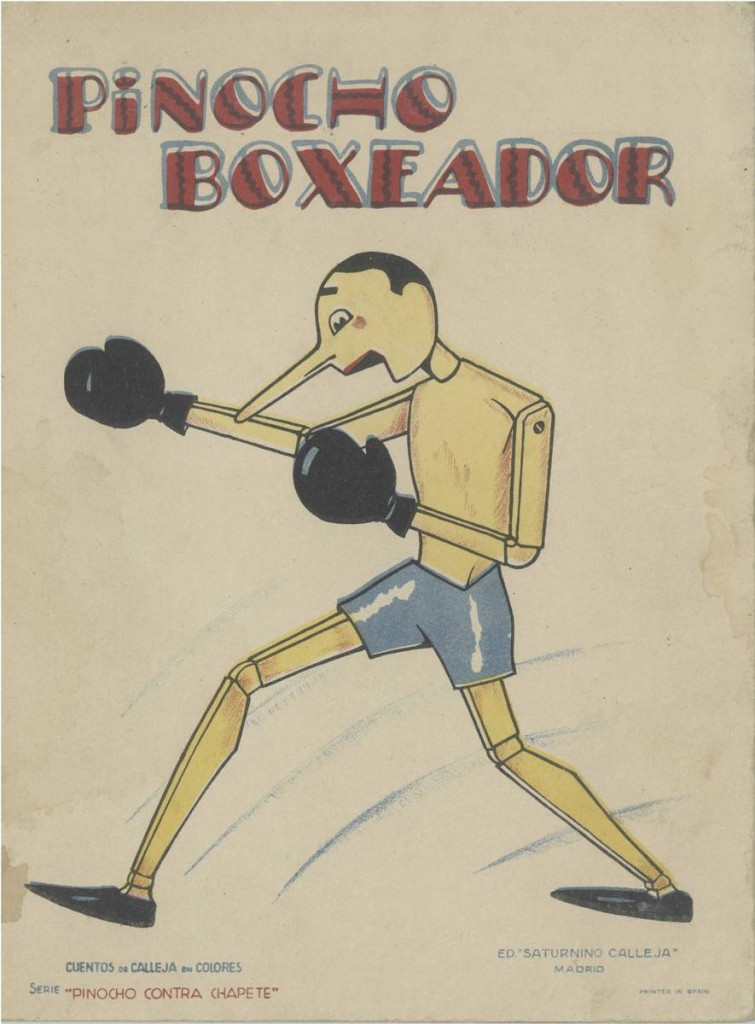

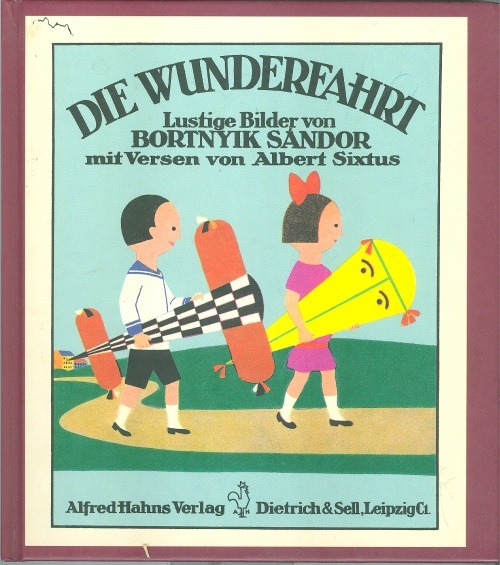

Sandor Bortnyik

Sandor Bortnyik only created one children’s book, the title of which Samuel Albert translated as Spot and Dot’s Adventurous Journey (shown below, published 1929).

There are apparently several versions of this, one of which has nonsensically playful verse – if I remember correctly, this version has neither been published nor translated. Â A Hungarian modernist, Bortnyik created posters, advertisements, and paintings. Â He was a major artist, but I’d never heard of him until hearing Albert’s talk.

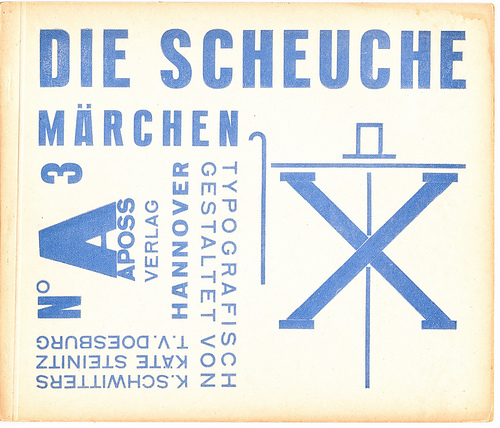

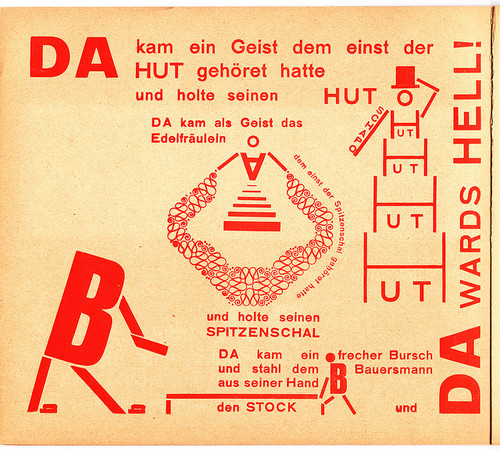

Kurt Schwitters

While we’re in the 1920s, I must here mention – as Hadassah Stichnothe and others did – the typographical delight that is Kurt Schwitters’ Die Scheuche (The Scarecrow, 1925).

A collection of Schwitters’ fairy tales, plus a full English version of the above appears in Schwitters’Â Lucky Hans and Other Merz Fairy Tales (translated by Jack Zipes, 2009).

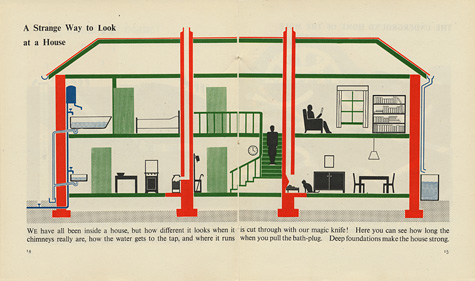

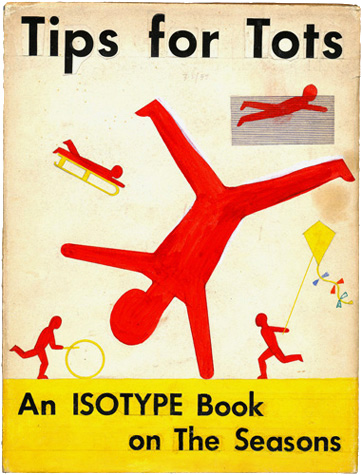

Otto and Marie Neurath’s ISOTYPE children’s books

Today, we’re familiar with silhouetted figures on signs, or graphs that use as a unit of measurement the image of the item measured.  Until hearing Hanna Melse’s paper, I didn’t know about the children’s books inspired by this pictorial language – which was named ISOTYPE (for International System Of TYpographic Picture Education).  Looking at the pictures, I thought that Chris Ware and Mark Newgarden would be especially interested – each image speaks with great economy and clarity, which is a stylistic trait they both admire.

above: Marie Neurath, Wonders of the Modern World (1948)

above: Otto and Marie Neurath, Tips for Tots (1944)

To learn more, see the ISOTYPE Revisited exhibit.

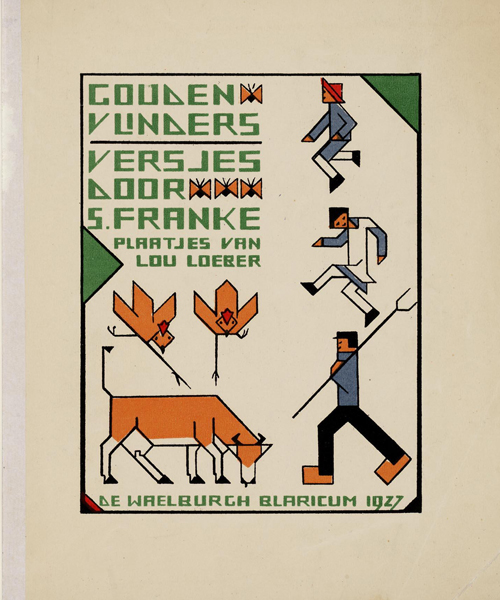

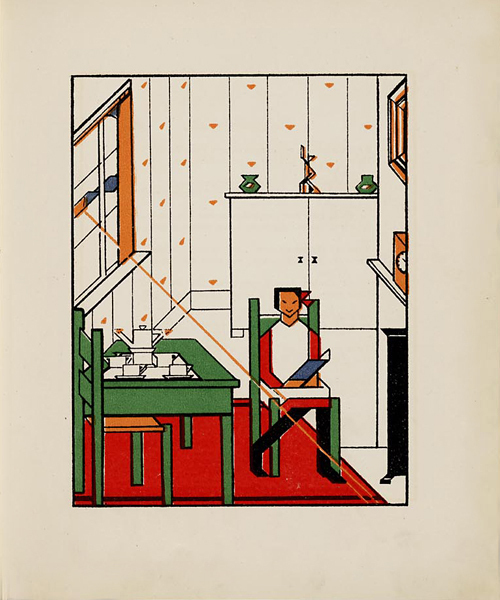

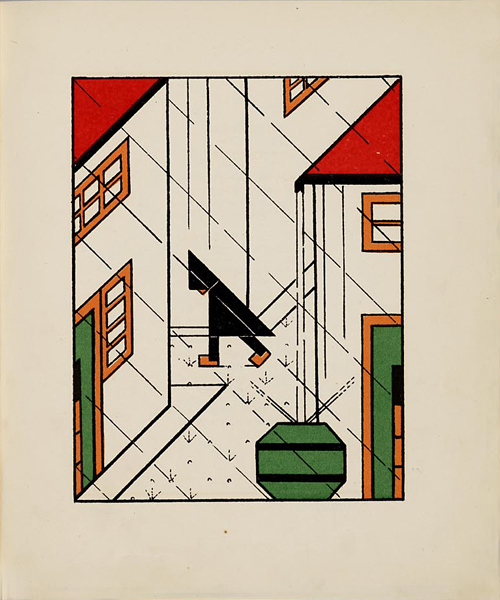

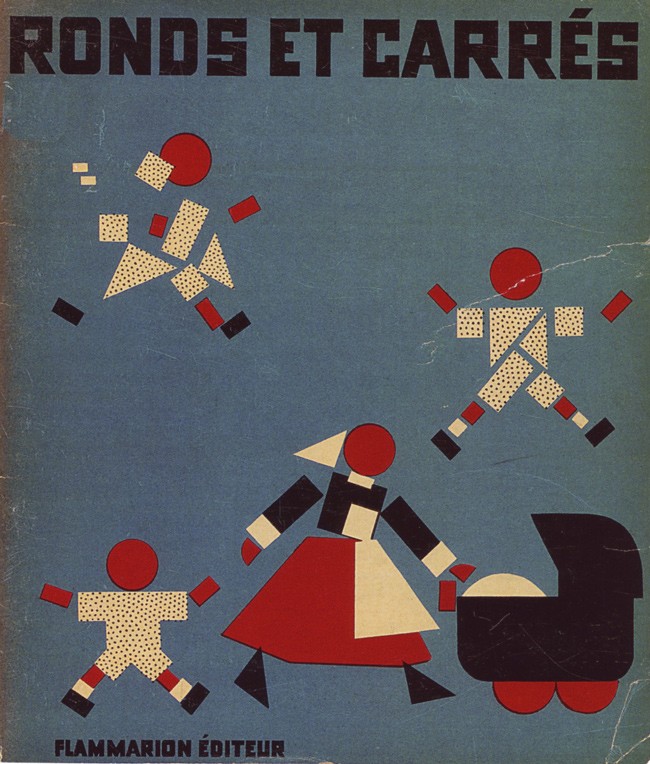

The Avant-Garde’s Legacy in French Children’s Literature

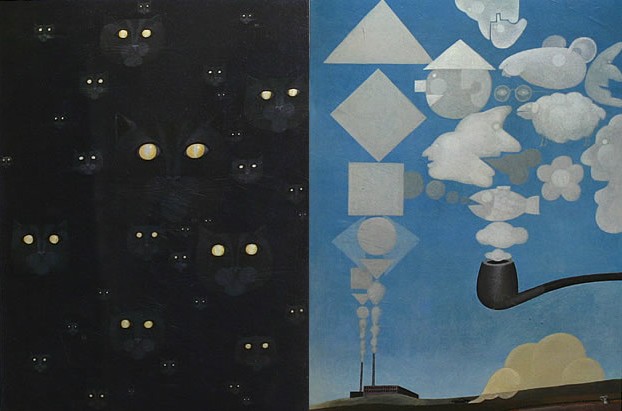

above: Nathalie Parain, ronds et carrés (round and square, 1932)

Sandra Beckett‘s discussion of the avant-garde and its legacy in French children’s literature was my favorite presentation. Â It gave me a greater understanding of French children’s literature’s willingness to take risks and push boundaries (in contrast to, say, American children’s literature). Â Beyond the paper’s thesis, I was intrigued by the books – some which I will seek for my own library, and others for my niece Emily’s Library.

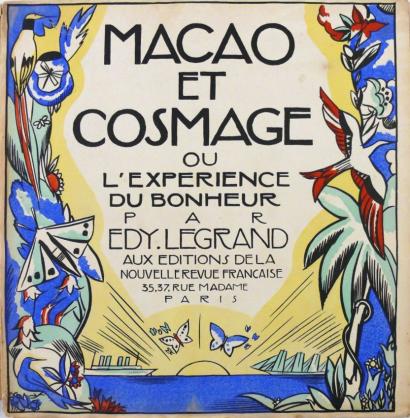

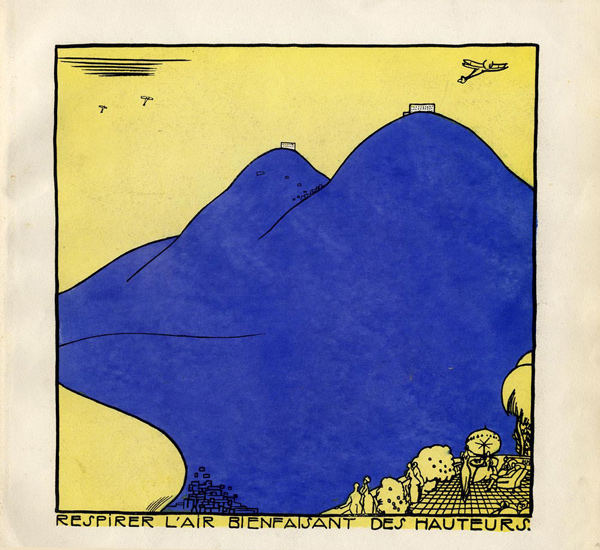

above and below: Edy-Legrand, Macao et Cosmage ou l’experience du bonheur (1919). Â Sandra Beckett calls it “the most visually daring work of an artist who would go on to become one of the premier illustrators of the 20th Century.” Â Edy-Legrand was only 18 at the time he created the book.

Evgeny Steiner would likely (and correctly) point out that Edy-Legrand’s images are more Art Nouveau than strictly surreal, but I presume that readers of this blog post won’t mind.

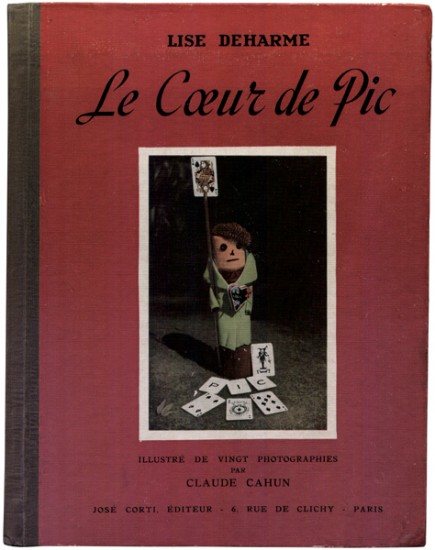

Above: Lise Deharme, Le Coeur de Pic, illustrated with photographs by Claude Cahun (1937).  Andre Breton, Man Ray, and other surrealists admired this book.  In his foreword to Le Coeur de Pic, Paul Eulard wrote, “The book has the age that you want to have.”

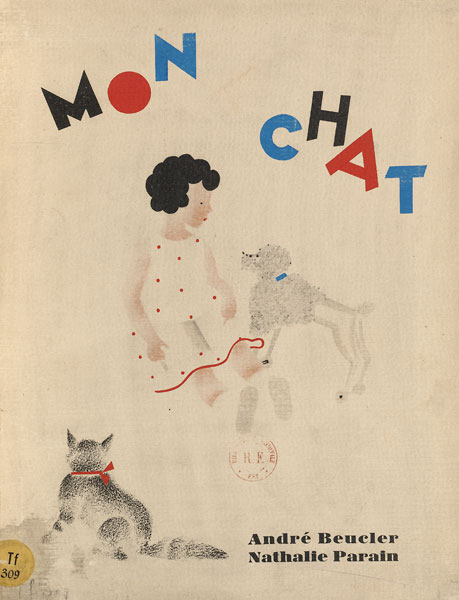

Above: Nathalie Parain, Mon chat (1930). Â You can also read the book in its entirety here.

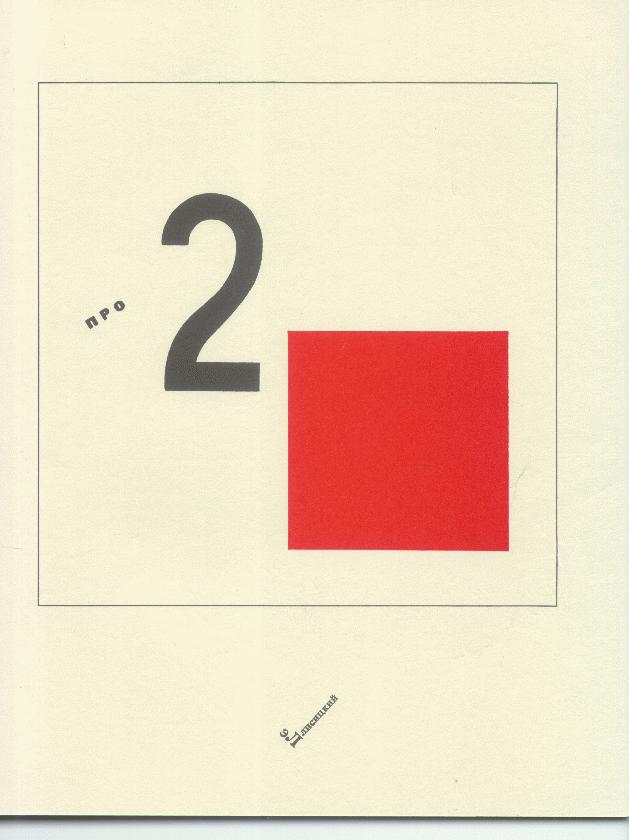

Sandra suggested that El Lissitzky’s About Two Squares (1922, above) influenced Anne Bertier’s Mercredi (2010, below).

This book (above) looks great & will definitely be joining Emily’s Library.

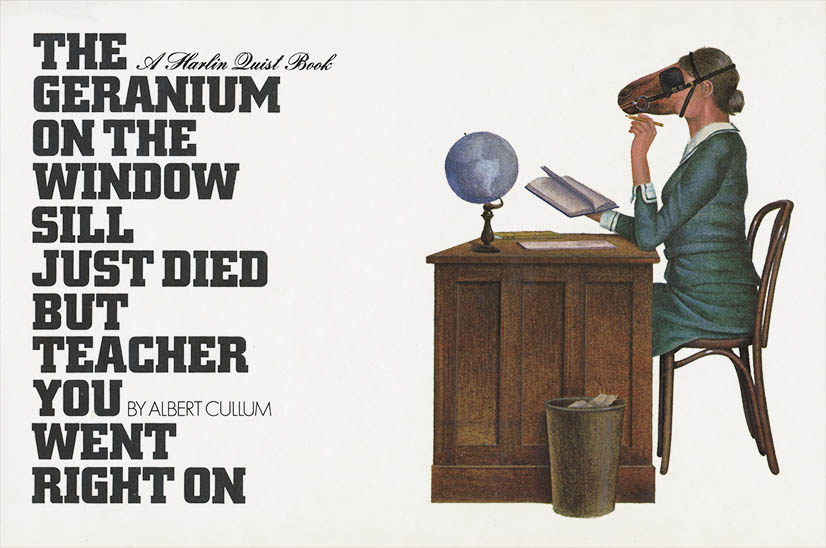

Moving into the 1960s and 1970s, publisher Harlan Quist’s pop art children’s books – also a focus of Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer’s talk – are all (or nearly all) out of print.  Many Quist books bring to mind Heinz Edelmann’s work (he was art director on Yellow Submarine), though not all do.

above: Albert Cullum, The Geranium on the Windowsill Just Died But Teacher You Went Right On (Quist, 1971).  The book has 30 illustrations, each one by a different artist.  Here’s the one by Nicole Claveloux:

And one by Cathy Deter:

One by Gerald Failly:

You can find many more pictures from The Geranium on the Windowsill… at Codex 99‘s post on the book (my source for the above images).

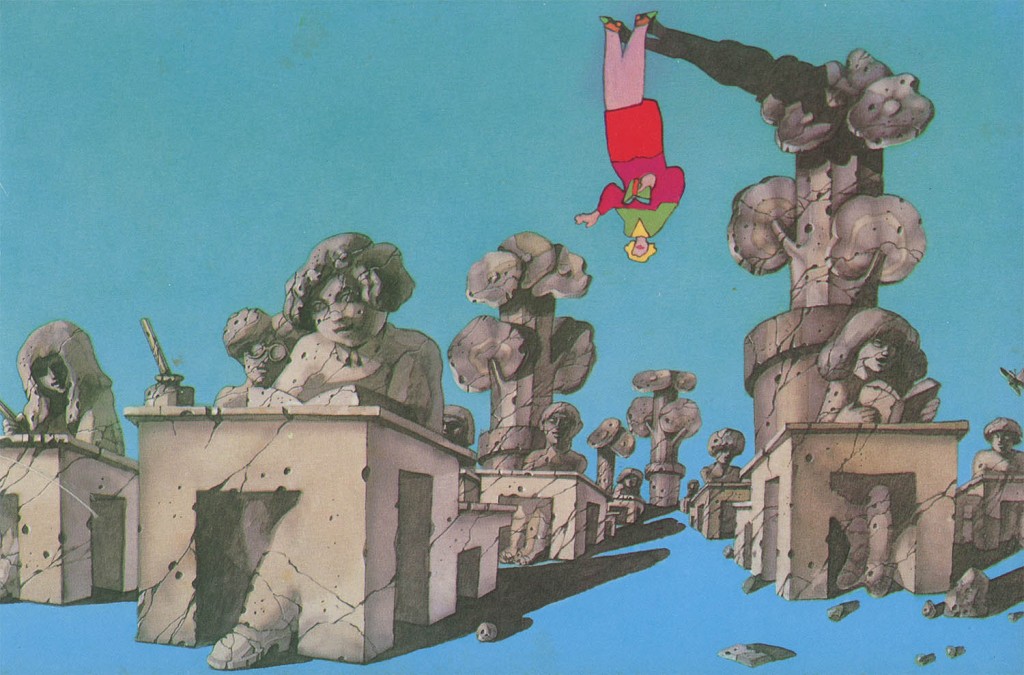

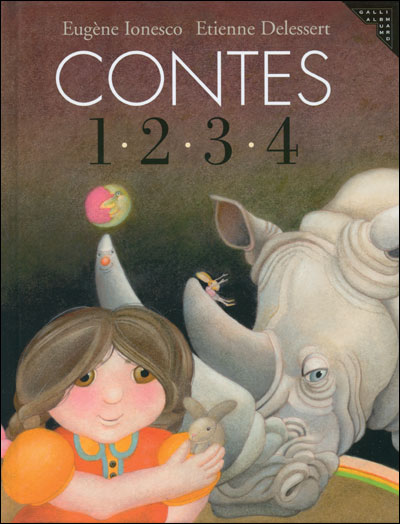

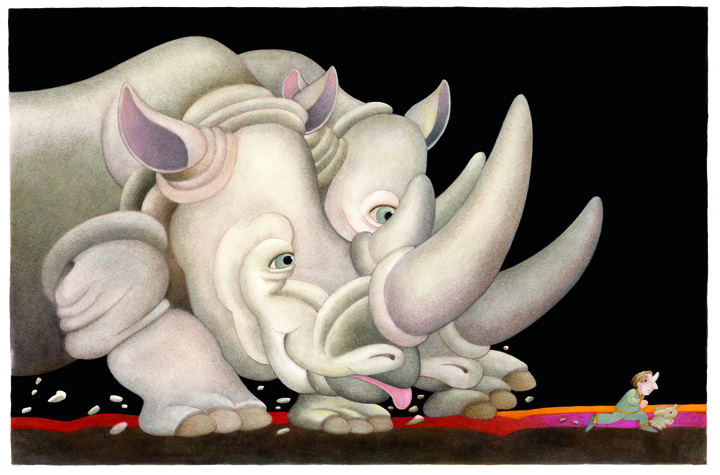

above: Eugène Ionesco and Etienne Delessert, Contes 1 2 3 4 (originally published 1969-1973), and recently republished in English as Stories 1 2 3 4 (McSweeney’s, 2012).

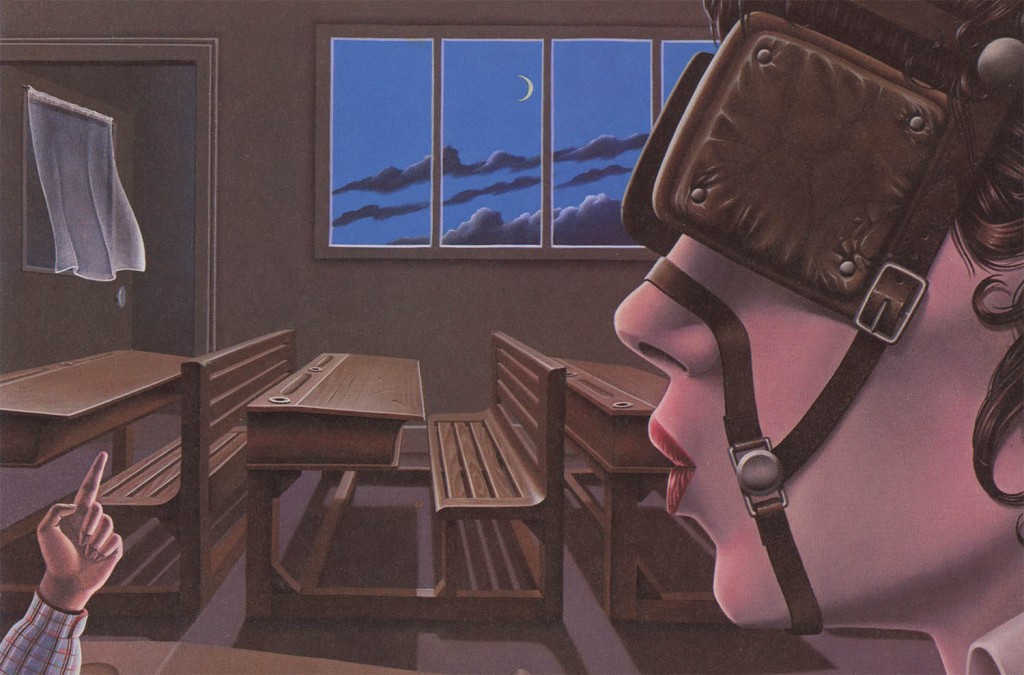

above: another illustration from Eugène Ionesco and Etienne Delessert, Contes 1 2 3 4.

Jules Walker Danielson has an extensive post on and interview with Etienne Delessert, which I recommend to you for further reading.

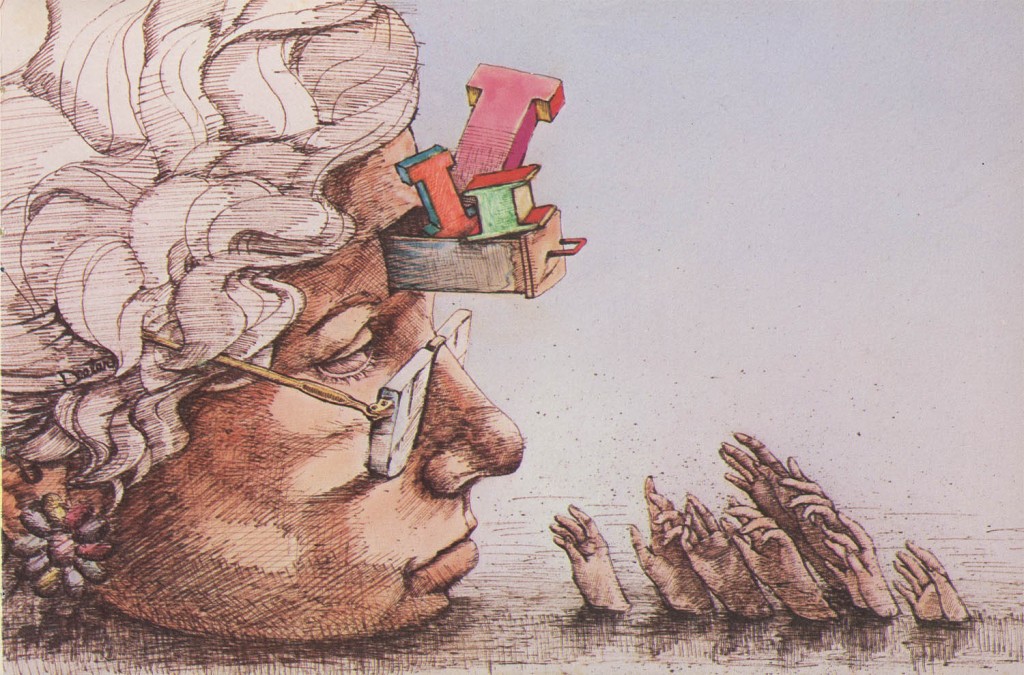

above: Jérôme Peignot and Robert Constantin, Au pied de la lettre (2003). Photo of slide created by Sandra Beckett.

Pop Art Children’s Books

I do realize that some of the above cross over into “Pop Art,” but since these next few images are from Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer’s talk (“Just what is it that makes pop art picturebooks so different, so appealing?”), I thought I’d give us a new section title.

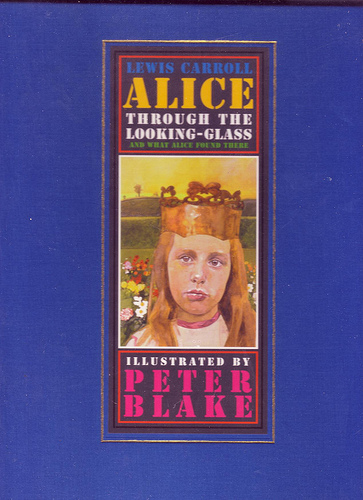

above: Peter Blake’s version of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (1972).

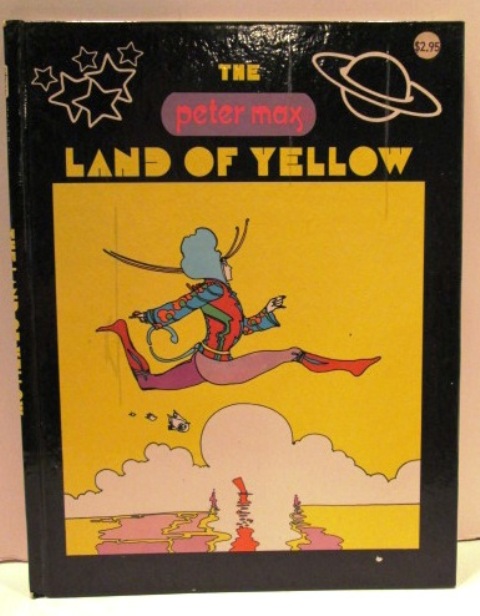

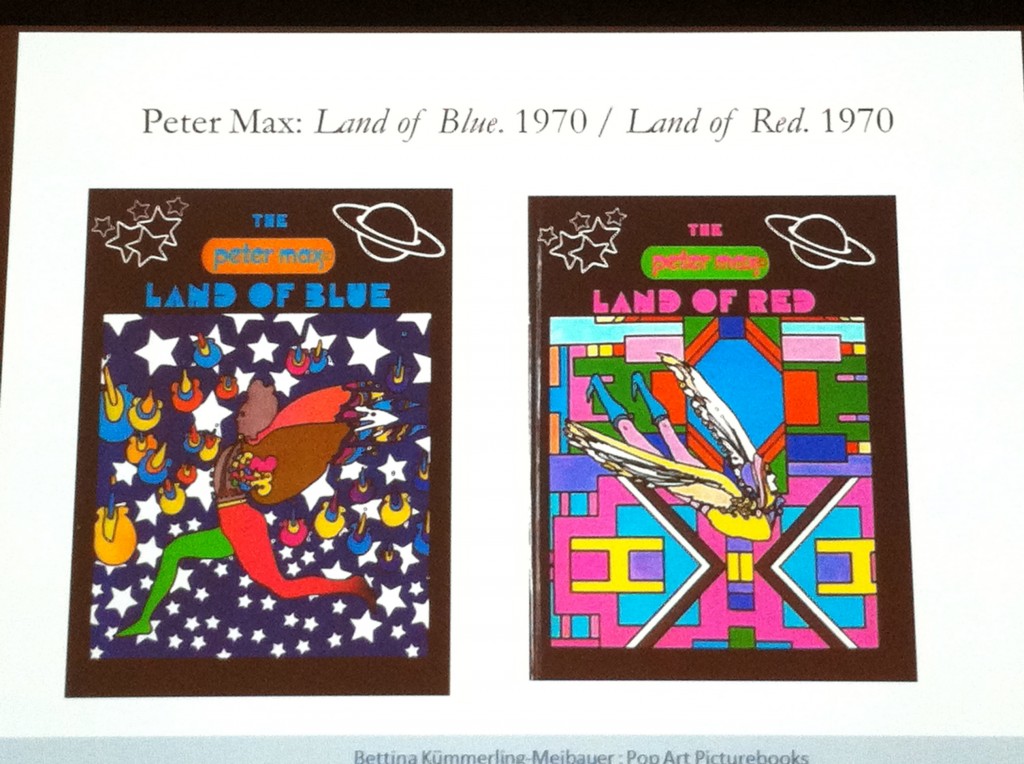

Inspired by Heinz Edelmann, Peter Max created The Land of Yellow (1970), The Land of Red (1970), and The Land of Blue (1970).

above: Peter Max, The Land of Yellow (1970).

above: Peter Max, The Land of Blue and The Land of Red (both 1970).  Photo of Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer’s slide.

above: two-page spread from Etienne Delessert’s How the Mouse Was Hit on the Head by a Stone and so Discovered the World (1971).  Original image on 50 Watts.

A Very British Avant-Garde

In her “A Very British Avant-Garde,” Kim Reynolds presented the results of the kind of archival research required to figure out just where these avant-garde books for children are being produced. Â To a one, I had never heard of any of the books she talked about.

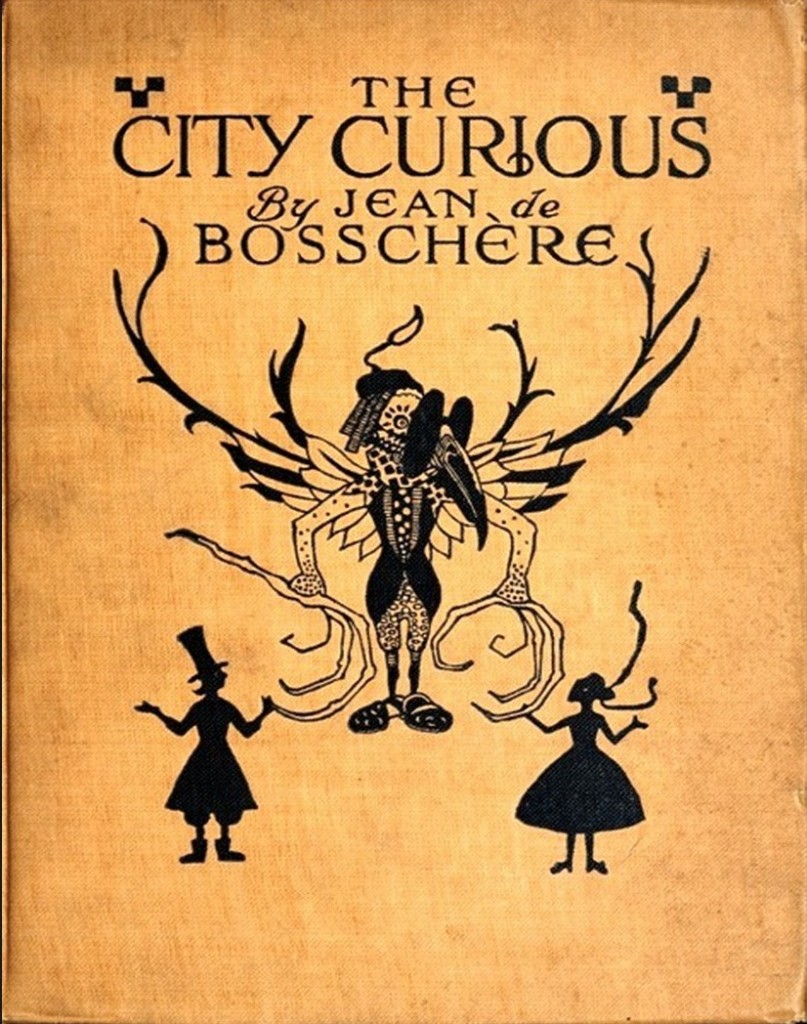

Kim reports that The Little Review called Jean de Bosschère’s The City Curious (1920) “a sinister little story.”

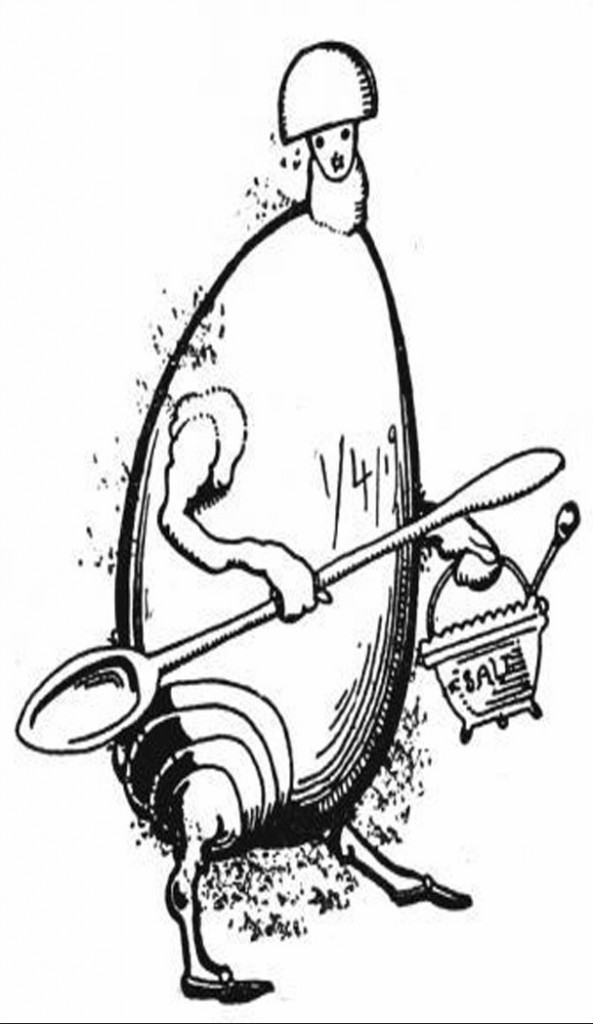

above: images from  Jean de Bosschère’s The City Curious (1920).  You can see more images from the book here.

above: my rather blurry photo of Kim’s slide featuring Enid Bagnol’s Alice and Thomas and Jane (1930).

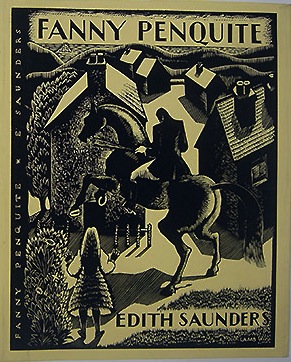

above:Â Edith Saunders, Fanny Penquite (1932). Â This more obscure title was published Oxford University Press and, as I recall, Kim was unable to find more information about the book’s author.

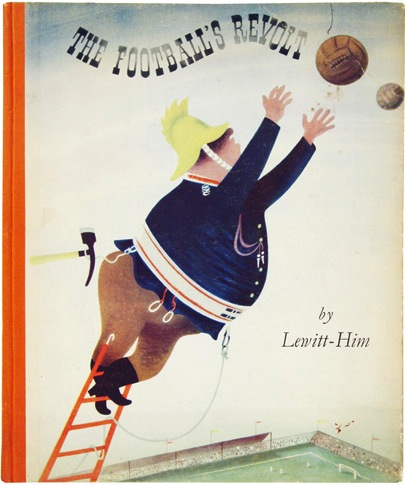

above: Lewitt-Him, The Football’s Revolt (1939) – a book about a football that decides it no longer wants to be kicked about!

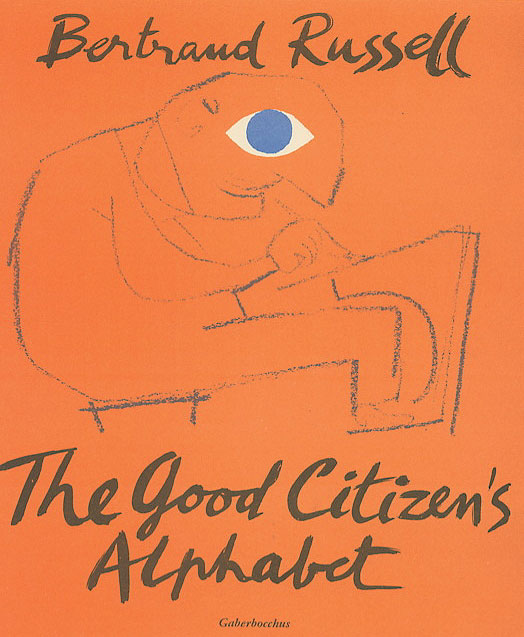

above: Bertrand Russell, The Good Citizen’s Alphabet, with drawings by Franciszka Themerson (1953).

I’ve left out a lot here, including Sirke Happonen‘s fascinating discussion of the production of Tove Jansson’s innovative Hur gick det sen? (1952) – the title means What Happened Next?, but the English translation bears the title The Book About Moomin, Mimble, and Little My.  And Olga Holownia’s award-winning presentation on the Icelandic avant-garde (which doesn’t really get going until the 1950s…!).  But the preceding, at least, offers a glimpse at some of the children’s books we learned about.

What’s harder to capture is the camaraderie of the event.  There were no competing sessions.  So, people from 25 countries all spent the better part of three days together.  Wisely, the organizers scheduled coffee breaks every couple of hours, and arranged for us all to have lunch together at the Museum of Work– a short walk from the conference venue.  Alas, there was little time to explore Norrköping, but we had evenings free.  I very much enjoyed hanging out with Kim Reynolds, Sandra Beckett, Olga Holownia, Nina Christensen, Sara Pankenier Weld, Anna Czernow, Evgeny Steiner, Samuel Albert, and many others whose names I should be mentioning here (apologies for omissions!).

Thanks to Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, Elina Druker, Maria Nikolajeva for organizing it.  Thanks to Allegra Roccato (who also took the above photograph) and the European Science Foundation for providing administrative and financial support.

And, coming up in my next post…: a few words on Tove Jansson’s Moomins, who are (inexplicably!) largely unknown in America.

Correction, 17 Oct. 2012, 5:25 pm.  Samuel Albert informs me that Bortnyik did not write the (unpublished) nonsensically playful verse for the book.  So, I’ve struck the words “by Bortnyik himself.”

Dave Ball

Charles Hatfield

Philip Nel

Perry Nodelman

Andre Alt

Suzanne Licht

Pingback: Children’s Literature and European Avant-Garde (Linköping University) | EQ

Emilio Quintana

Mark Newgarden

Philip Nel

Emilio Quintana

Philip Nel

Pingback: Image&Word » Blog Archive » Children’s Literature and European Avant-Garde, Norrköping

Pingback: Laurence › La maison d’édition Gaberbocchus