Last month, there was some on-line discussion about this quote (from me) in a CNN.com article:

But Nel argues that the answer isn’t simply removing “problematic” children’s classics like Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” which uses the N-word 219 times, from school reading lists.

Such stories, “if used carefully, appropriately and in context can be a way to educate people about racism,” he says.

Teaching problematic children’s classics can allow children of color to critique and disagree with a book, express anger at oppression and find the language to talk about racism while also teaching white children to identify racist ways of thinking and challenge their own racialized assumptions, Nel explains.

My thanks to all who have participated in this conversation, and my apologies for joining it a little late.

Oh, god. This makes me ragey: pic.twitter.com/z3Krc9M5RB

– Mom’Baku Kennedy (@MicaKenBooks) October 23, 2018

Mica Kennedy (@MicaKenBooks on Twitter) embeds the above quotation and then asks, “These texts are inherently damaging – yet somehow, it’s the job of black children to rise above and make this a teaching moment? I. Think. The. Hell. Not.”

This CNN article quoting Philip Nel just makes me angry each time I look at it.

Native/Kids of color will do what?! https://t.co/1GI7wAmArB

– Dr. Debbie Reese (@debreese) October 23, 2018

Dr. Debbie Reese (@debreese on Twitter) writes, “This CNN article quoting Philip Nel just makes me angry each time I look at it. Native/Kids of color will do what?!”

In response, Dr. Laura M. Jimenez (@booktoss on Twitter) writes, “There is so much wrong with the paragraph. So, so, so wrong. Mostly, @philnel’s white privilege is visible. Hell, his privilege is having a damn parade!”

There is so much wrong with the paragraph. So, so, so wrong. Mostly, @philnel ‘s white privilege is visible. Hell, his privilege is having a damn parade ! #kidlitsowhite #WeNeedDiverseBooks

– Dr. Laura M. Jimenez (@booktoss) October 24, 2018

These critics helpfully highlight the context absent from that quotation, and I am grateful to them for doing so. While such texts can provide a teaching moment, it is not the job of Black children to (if I may quote Mica Kennedy) “rise above and make this a teaching moment.” I can see how the above quotation might convey that impression, but I emphatically do not recommend a pedagogical practice that relies upon Black, indigenous, and children of color to educate their peers. Thanks to Ms. Kennedy, Dr. Reese, and Dr. Jimenez for their critiques.

This blog post is my attempt to publicly counter the potential harm that may be done if people walk away from the CNN.com article with the wrong impression. I wouldn’t want the excerpted quotation to enable the perpetuation of racist harm in classrooms. For example, let us imagine that a child or parent of color objects to a teacher’s inclusion of Huckleberry Finn or Little House on the Prairie, and this teacher then cites that quotation as justification for his or her argument. Indeed, should that (or something similar to that) happen, please direct the teacher to this blog post. Then, you can tell the teacher, “Actually, no. That is not what he meant at all.”

Here’s a little context missing from the CNN.com quotation, but present in Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature and the Need for Diverse Books (2017). Bowdlerized versions of racist classics aspire to remove the racism but instead re-encode it more subtly. So, if (and only if) one is going to read those books, better to read the un-Bowdlerized versions and to do so — in context – in the context of books that offer accurate representations and that debunk the racism.

Here’s a little context missing from the CNN.com quotation, but present in Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature and the Need for Diverse Books (2017). Bowdlerized versions of racist classics aspire to remove the racism but instead re-encode it more subtly. So, if (and only if) one is going to read those books, better to read the un-Bowdlerized versions and to do so — in context – in the context of books that offer accurate representations and that debunk the racism.

That said, and as also noted in Was the Cat in the Hat Black?, there are excellent reasons for not teaching or reading such books at all. Here are two paragraphs from Chapter 2 of the book:

Advocates of bowdlerizing or banning these novels correctly point to the powerful role that the original versions of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Doctor Dolittle have played in dehumanizing people of color. As New York librarian Isabelle Suhl wrote in 1968, “what justification can be found by anyone–and I ask this particularly of those adults who still defend Lofting–to perpetuate the racist Dolittle books? How many more generations of black children must be insulted by them and how many more white children allowed to be infected with their message of white superiority?” Racist texts can inflict real psychic damage on children of all races, but the child who is a member of the targeted group sustains deeper wounds than the child who is not. The racial ideologies of Dahl, Lofting, Travers, and Twain all but ensure that children who are (and have historically been) the targets of prejudice will suffer in ways that White children will not. The White child who encounters the n-word or Prince Bumpo or an Oompa-Loompa has the unearned privilege of not seeing people of her or his race being stereotyped. That said, as Suhl notes, such books damage White children, too, conveying to them that they are more important, and that dominating people of color is acceptable. Prejudice harms different groups in different ways, and its harmful effects are not distributed equally. Even assigning such a text risks reinforcing structural racism.

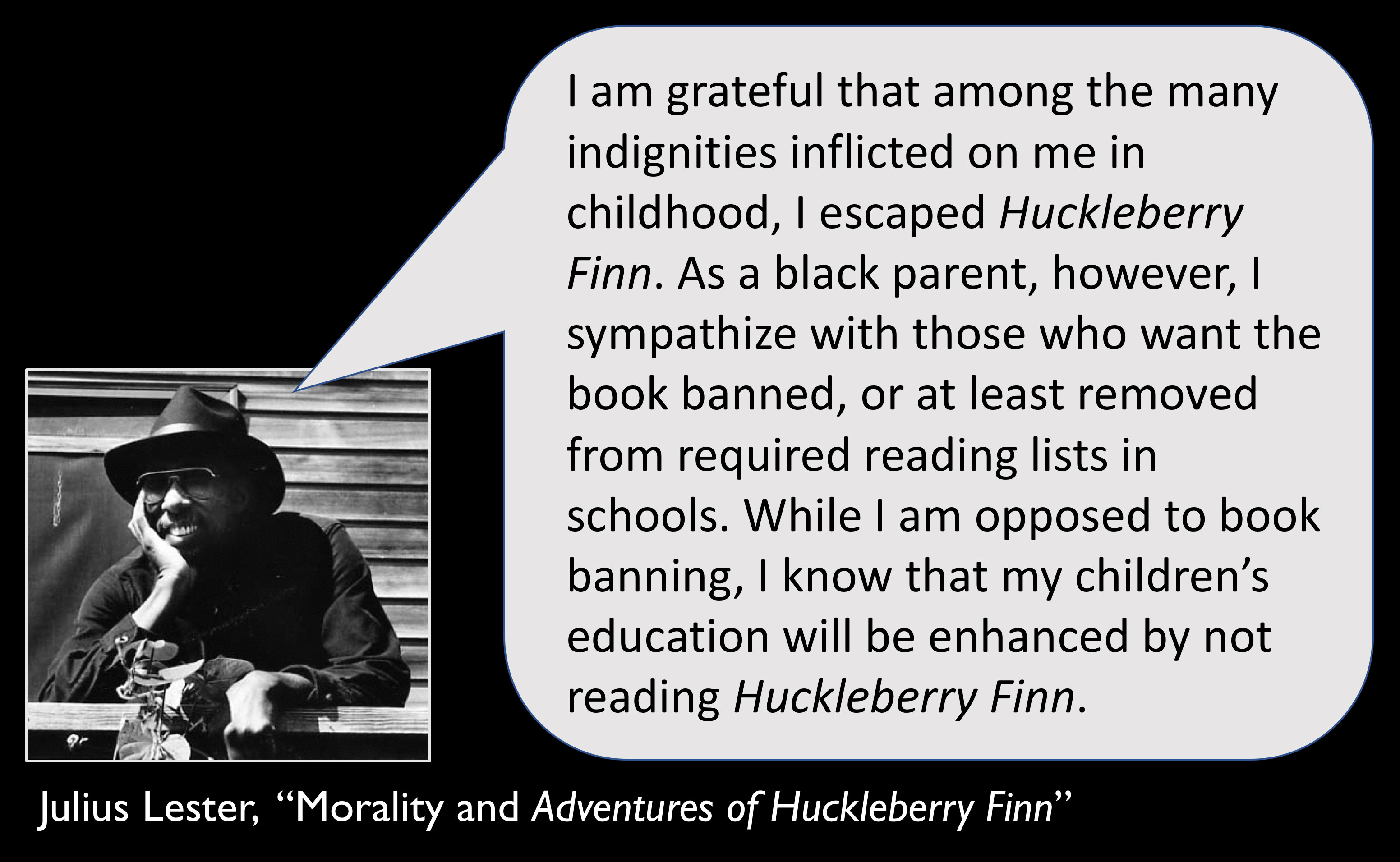

Indeed, there is a case to be made for removing racist books from grade-school curricula. Julius Lester has admitted that he is “grateful that among the many indignities inflicted on me in childhood, I escaped Huckleberry Finn.” He adds that, “as a black parent,” he sympathizes “with those who want the book banned, or at least removed from required reading lists in schools. While I am opposed to book banning, I know that my children’s education will be enhanced by not reading Huckleberry Finn.” John H. Wallace goes even further, arguing that Huckleberry Finn “should not be used with children. It is permissible to use the original Huckleberry Finn with students in graduate courses of history, English, and social science if one wants to study the perpetuation of racism.” We could develop this line of reasoning further, and argue that the best way to hasten the decline of a racist classic–and thus the racism it may propagate–is not to teach it at all, at any level.

The chapter then goes on to explore how racist children’s books – used in context of accurate, anti-racist children’s books – might be pedagogically useful. And it is quite specific in calling out the racism of these novels. For instance, as Jonathan Arac, Julius Lester, and many others have pointed out, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is not the progressive anti-racist classic that it’s promoted as being.

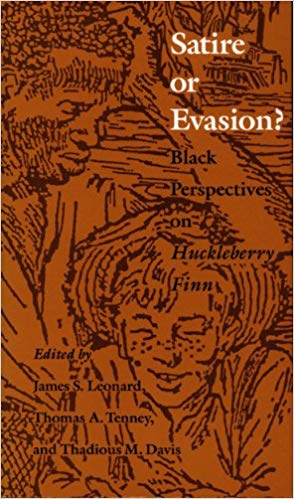

For more on why not to teach Huckleberry Finn, see Satire or Evasion?: Black Perspectives on Huckleberry Finn, edited by James S. Leonard, Thomas A. Tenney, and Thadious M. Davis (1992). The book includes Julius Lester’s “Morality and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” and John H. Wallace’s “The Case Against Huck Finn,” both of which I quote above. See also Jonathan Arac’s Huckleberry Finn as Idol and Target: The Functions of Criticism in Our Time (1997), which addresses how the novel’s “hypercanonization” has obscured its racism. For more on why not to teach Huckleberry Finn, see Satire or Evasion?: Black Perspectives on Huckleberry Finn, edited by James S. Leonard, Thomas A. Tenney, and Thadious M. Davis (1992). The book includes Julius Lester’s “Morality and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” and John H. Wallace’s “The Case Against Huck Finn,” both of which I quote above. See also Jonathan Arac’s Huckleberry Finn as Idol and Target: The Functions of Criticism in Our Time (1997), which addresses how the novel’s “hypercanonization” has obscured its racism.

On the potential dangers that racist literature poses to Black, indigenous, and children of color, see Oyate’s “Living Stories”. For advice on how to tell whether a book is racist, see Oyate’s “How to Tell the Difference” and “Additional Criteria.” |

Racism damages everyone, but inflicts greater pain on its targets. As I say in the CNN.com article, “The stories that children read at a young age tell them who matters and who doesn’t matter, who’s human and who isn’t human. A story doesn’t have to tell us that explicitly. It can tell us that by failing to represent certain groups of people – omission tells us that these groups of people are not important.”

* * * * *

Thanks to Allie Jane Bruce for alerting me to the existence of this debate. When the CNN article ran, I was (and still am) traveling, and so I noted the appearance of the piece but didn’t have a chance to do more than glance at it.

As you may or may not have noticed, my use of social media has declined over the past year or so. I check in on Facebook once every couple of weeks. I am still on Twitter, but (with the exception of three days in Atlanta and two in England) have been on Central European Time since the first of August. So, I am sure I’m missing conversations that I should be noticing.

I also don’t fault the CNN piece for lacking the full context. Several reasons. First, the exigencies of news media tend to lose the nuances. Elisions are endemic to the medium. Second, journalism is a tough job: writers have to balance a range of information in a very compact form, and yet manage to sustain a reader’s attention. They also may not have full editorial control. A third reason that this may not be the journalist’s fault at all: I have no recollection of the interview. When the journalist kindly wrote me to say that the piece had been published, I then noted (via our earlier embedded emails at the bottom of the note) that we had talked back in April. So, during our interview, it’s entirely possible that I failed to emphasize the context provided above. If that’s the case, then the fault is entirely mine.

Two more concluding thoughts. First, I should not take for granted that everyone is aware of the unavoidable elisions and compressions of the news media. Over the course of my career, I’ve been interviewed hundreds of times. As a result, I take for granted that the entire arc of one’s argument may not appear in full. However, I recognize that my experience is unusual and so I need to do a better job monitoring – and, in cases like this, responding to – how statements are represented.

Second, and as noted in Was the Cat in the Hat Black?,

While it is impossible to grow up in a racist culture and not absorb some of its messages, it is very easy to be unconscious of what you have absorbed. That is how dominant ideologies work: their messages seep in subtly, persistently, without your noticing. When I was preparing to teach the book in a college class, I picked up Helen Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo for the first time. As I read it, I had the unsettling experience of realizing that I already knew the story. This was not the first time I had encountered Little Black Sambo. Had I read Bannerman’s version? Or perhaps an edition with more grotesque racial caricature, such as John R. Neill’s? What other half-remembered stories (suffused with racial caricature or otherwise) were lurking in my subconscious? As I mentioned in the introduction, only when I reflect upon the racist culture of my childhood–the Gollies, the Uncle Remus stories, Little Black Sambo, the near-absence of narratives featuring people of color–can I begin to contemplate how it shaped my own racial and, yes, racist assumptions about other people. A writer, artist, or critic may not intend to perpetuate stereotypes, but–especially when left unexamined–ideology trumps intention…. [W]ell-intentioned people can still act in ways that reinforce racism, unaware that they are doing so. Since the United States is such a segregated country, White people live in an environment structured to prevent our awareness of race and racism. These geographies and the culture itself make it easy for Whites to avoid reflecting upon our raced selves. All who work in the field of children’s literature and culture need to reflect, and strive to do better.

As the critiques generously provided by Ms. Kennedy, Dr. Reese, Dr. Jimenez and others indicate, I need to do better. Here are some resources to help all of us do better:

- American Indians in Children’s Literature, established in 2006. Debbie Reese’s site offers “critical perspectives and analysis of indigenous peoples in children’s and young adult books, the school curriculum, popular culture, and society.”

- Brown Bookshelf, established in 2007: “A group of authors and illustrators who came together to push awareness of the myriad of African American voices writing for young readers.”

- CrazyQuiltEdi‘s Diversity Resources, from Edi Campbell.

- Latinxs in KidLit. As it says, “Exploring the world of Latinx YA, MG, and children’s literature.”

- Lee & Low Books have many diversity initiatives, including the Diversity Baseline Survey for publishers, its Diversity Gap Studies, and many blog posts on diversity, race, and representation.

- Oyate’s Resources “that teach respect for Native peoples, and help parents and educators to provide their children with historically accurate, culturally appropriate information about Native peoples.”

- Reading While White, a group of White librarians pledges to “hold ourselves responsible for understanding how our whiteness impacts our perspectives and our behavior.” They publish thoughtful essays and book reviews, and offer useful resources. As they say, “As White people, we have the responsibility to change the balance of White privilege.”

- Research on Diversity In Youth Literature, open-access journal edited by Sarah Park Dahlen and Gabrielle Halko.

- Teaching for Change, founded in 1990, is dedicated to using education to promote social justice. As its website explains, it “provides teachers and parents with the tools to create schools where students learn to read, write and change the world.” The organization offers an anti-bias curriculum, resources for teaching about the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, recommended books, and ways for parents to get involved.

- We Need Diverse Books is Ellen Oh, Malinda Lo, and Aisha Saeed’s “grassroots organization of children’s book lovers that advocates essential changes in the publishing industry to produce and promote literature that reflects and honors the lives of all young people.” It includes resources for writers (including advice, awards, and grants) and readers (on where to find diverse books), and opportunities for you to get involved.