When I started writing what was then a biography of Crockett Johnson (back in the late 1990s), I thought: When I finish this, I really will have achieved something. Even as I wrote other books, I continued to think of the biography – which became a double biography of Johnson and Krauss – as The Big Achievement. Sure, Dr. Seuss: American Icon (my third book, published 2004) was OK, and, yes, the media attention it received was certainly flattering. But the biography would be the Truly Important Work.

When I started writing what was then a biography of Crockett Johnson (back in the late 1990s), I thought: When I finish this, I really will have achieved something. Even as I wrote other books, I continued to think of the biography – which became a double biography of Johnson and Krauss – as The Big Achievement. Sure, Dr. Seuss: American Icon (my third book, published 2004) was OK, and, yes, the media attention it received was certainly flattering. But the biography would be the Truly Important Work.

So, you might (or might not) be asking: (1) Why make this distinction between the biography and my other work? (2) Do I still make this distinction? (3) And, now that the biography is published, does it feel as “Truly Important” as I thought it would?

1. Why make this distinction?

The degree of original research required far surpassed that needed for my other books. I interviewed over 80 people, investigated over three dozen archives and special collections, read everything written by or about Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss, and consulted additional hundreds of articles and books. I looked at birth certificates, marriage certificates, census data, property deeds, wills, century-old insurance company maps, and Johnson’s FBI file. If I hadn’t gathered (some of) this information, it would be lost forever. Coping with the mortality of one’s sources is a big challenge for the biographer. Maurice Sendak, Remy Charlip, Syd Hoff, Mischa Richter, Else Frank (Johnson’s sister), Mary Elting Folsom (author who knew Johnson in the 1930s), Gene Searchinger (filmmaker who knew them both), and so many others taught me much about Johnson and Krauss. They have since passed away. If I hadn’t recorded their stories, that information would be gone.

The biography has been more challenging than any other project I’ve tackled, bar none. As I’ve observed before (probably on this blog, and certainly in the talk I gave last month at the New York Public Library), a biography is a jigsaw puzzle, but this puzzle has no box, missing pieces, and no sense of how many pieces you’ll need. There are also the challenges of creating character, knowing which details to omit, and finding a narrative structure. Life has no narrative, but biography has to have a narrative. I have no training in creative writing, but – for this book – I had to try to think like a creative writer.

In sum, there are reasons that a biography takes so long to write….

2. Do I still make this distinction?

![]() Sort of. The distinction reflects a tendency to devalue the discipline in which I was trained – the sense that Dr. Seuss: American Icon, though it does draw on considerable original research, is ultimately “just interpreting texts.” In contrast, rigorous historical research, actually uncovering new information, is much more important work. But I say “sort of” because of course there are truly insightful ways of interpreting texts, illuminating formal strategies, transformative critical approaches – Robin Bernstein’s Racial Innocence is one such book. It’s a paradigm-shifter. As I’ve noted before, I don’t have the kind of mind that writes a paradigm-shifting book.

Sort of. The distinction reflects a tendency to devalue the discipline in which I was trained – the sense that Dr. Seuss: American Icon, though it does draw on considerable original research, is ultimately “just interpreting texts.” In contrast, rigorous historical research, actually uncovering new information, is much more important work. But I say “sort of” because of course there are truly insightful ways of interpreting texts, illuminating formal strategies, transformative critical approaches – Robin Bernstein’s Racial Innocence is one such book. It’s a paradigm-shifter. As I’ve noted before, I don’t have the kind of mind that writes a paradigm-shifting book.

My strength is that I work hard. A biography plays to that particular strength – and perhaps this is one reason that it interests me. It interests me for other reasons, too (the “detective work” part, for example). But it is one intellectual arena where I can do something well: work really hard. Superior intelligence may elude me, but I can put in the hours! So, in some ways I still make the distinction (the amount of research, the box-less puzzle, etc.), but in other ways I do not.

3. Now that it’s published, does it feel like such a Big Achievement?

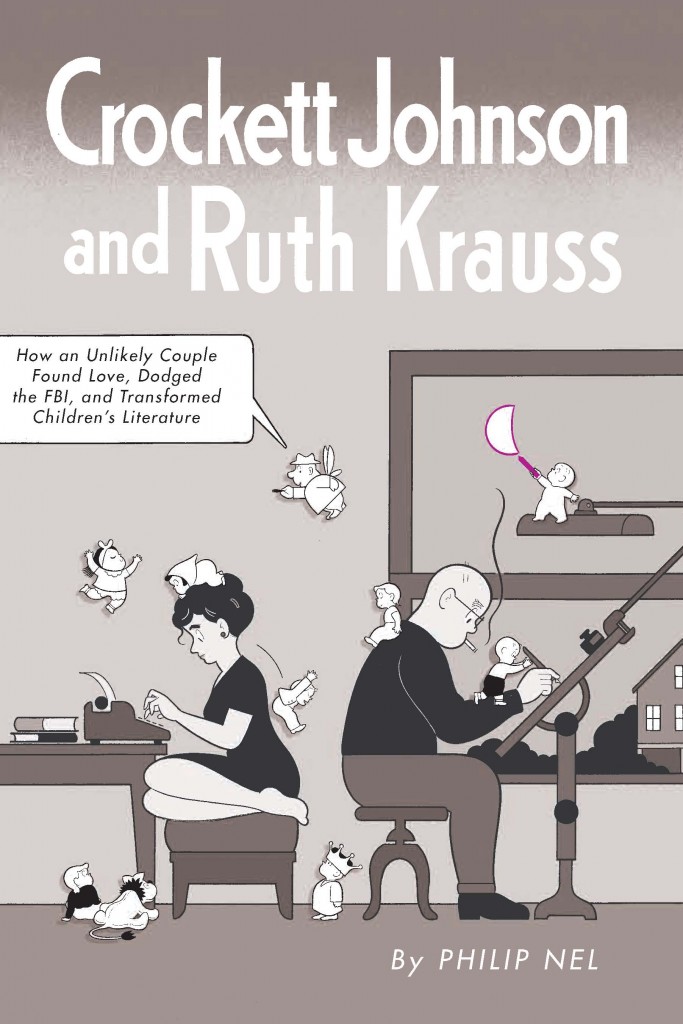

The response (mostly positive) has been a good feeling. In addition to nice reviews from Anita Silvey, Roger Sutton, Maria Tatar, Kirkus, and the Wall Street Journal, other Notable People Whose Work I Admire have been very complimentary. With apologies for the name-dropping, those people include Chris Ware (who also created the beautiful cover), Dan Clowes, Mark Newgarden, Paul Karasik, Lane Smith, Susan Hirschman, George Nicholson, and Michael Patrick Hearn. Given that Maurice Sendak even responded positively to an early, detail-clogged, incomplete draft, it is of course possible that these folks are simply being kind, and forgiving the book’s many infelicities (as I expect Maurice was). But I’m accepting their kind assessments as genuine because, well, it makes me happy to do so!

That said, as I’ve documented on this blog, the editing process was not entirely harmonious. Some cuts were good ones; others were not. My copy-editor was an historian by training; I needed a writer of fiction. My changes to her edits resulted in some errors, including (as one audience member pointed out at the NYPL last month) a typo in the first sentence. The press refused to change some errors I found in the page proofs (though it did change others). The paperback is priced not at $27, as I had originally been told it would be, but at $40 — this makes it harder to schedule signings because who buys a $40 paperback? These problems make me not want to think about the book at all.

I realize that I should let this go. Publishers introduce errors into manuscripts. Bureaucracies do not always function smoothly. Humans are prone to error, fatigue, and failures of judgment.

Fortunately, despite my irritations, the book does feel like an achievement. Given how long it took to write (I started in 1999), it is thus far my life’s work. It is a big deal.

But there is little time to dwell upon one’s achievements. There are new projects (such as The Complete Barnaby, volume 1 of which is due out early next year), tenure-and-promotion letters to write, letters of recommendation to write, (other people’s) book proposals to review and manuscript to edit, (my) conference abstracts to create and talks to write, planes to catch, meetings to attend, syllabi to revise, syllabi to invent, papers to grade, classes to teach, students to meet. Being an academic is a great job, the work is rewarding, and I feel privileged to do it — even though I rarely have the time to notice those rewards or recognize that privilege. It’s one of the paradoxes of being a professor.

Charles Hatfield

Philip Nel

Joseph Thomas

Philip Nel

Joseph Thomas