On the 50th anniversary of the assassination of President Kennedy, I happen to be staying at the Washington Hilton – the hotel in front of which President Reagan was not assassinated 32 and a half years ago.

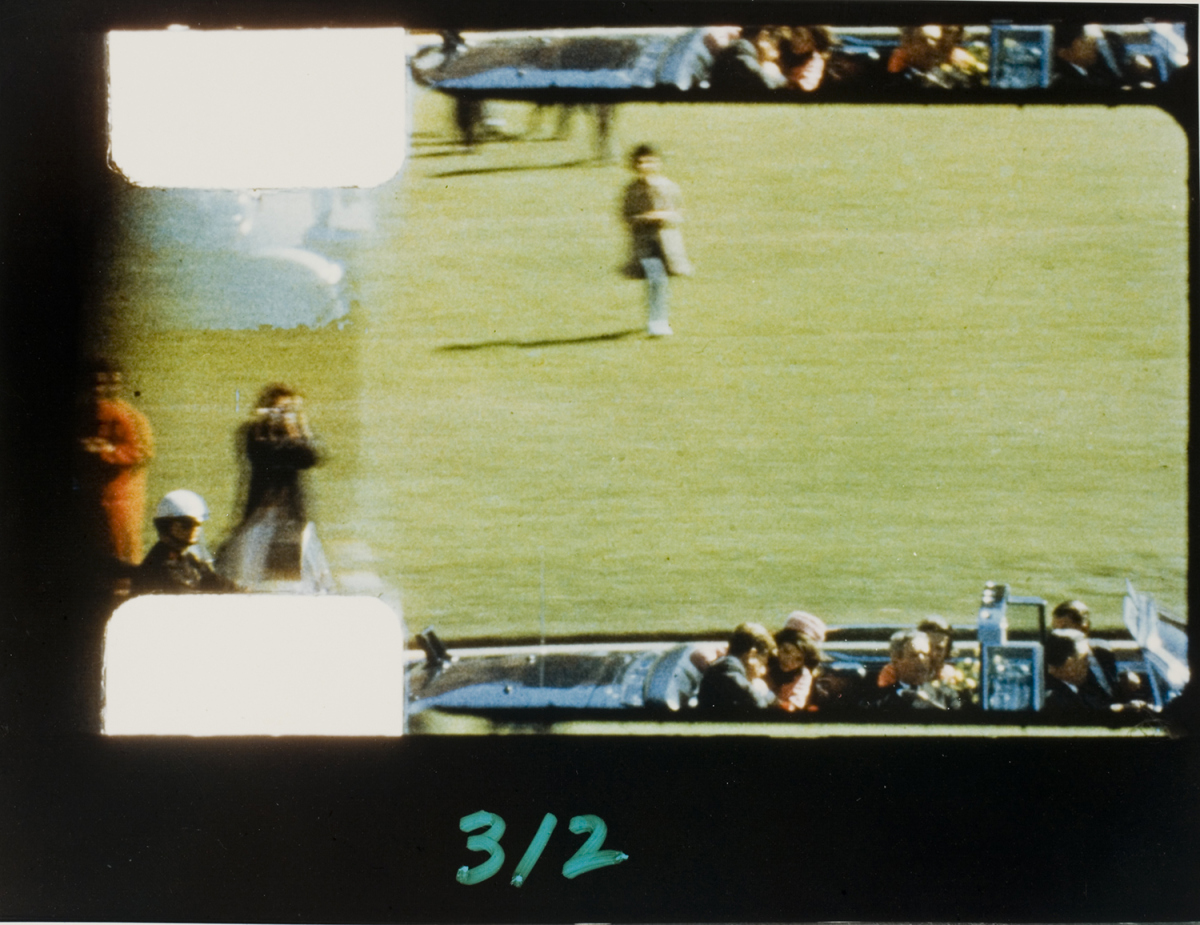

Don DeLillo called the Kennedy assassination, “The seven seconds that broke the back of the American century.” But I had not yet been born on November 22, 1963.

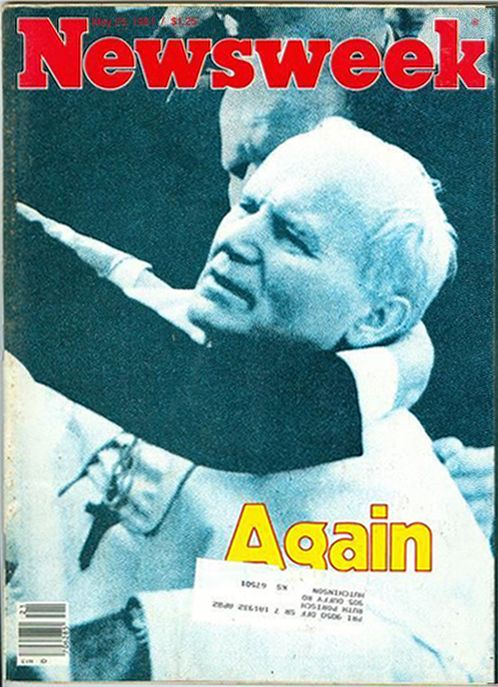

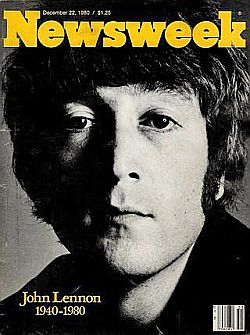

The murders and attempted murders that color my childhood are John Lennon (killed December 1980), Reagan (shot in March 1981), the Pope (shot in May 1981), and Anwar Sadat (killed October 1981). I saved the issues of Newsweek magazine that covered each event. The cover for the Pope issue featured a black-and-white photo, moments after the assassination attempt. The caption, in bright letters, was: “Again.”

The murders and attempted murders that color my childhood are John Lennon (killed December 1980), Reagan (shot in March 1981), the Pope (shot in May 1981), and Anwar Sadat (killed October 1981). I saved the issues of Newsweek magazine that covered each event. The cover for the Pope issue featured a black-and-white photo, moments after the assassination attempt. The caption, in bright letters, was: “Again.”

Kennedy’s assassination reached me via popular culture, in collections of Life magazine photographs, or the Kinks’ “Give the People What They Want” (1981), which includes the line: “When Oswald shot Kennedy, he was insane / But still we watch the re-runs again and again. / We all sit there glued while the killer takes aim…. / ‘Hey, mom! There goes a piece of the president’s brain!’”

That last line neatly encapsulates my 11-year-old self’s experience of the Reagan assassination attempt. Television news played the clip so frequently that it began playing on an endless loop in my head, too. My friends and I began re-enacting the event on the playground. The person playing Reagan would wave, and then duck into an imaginary car, pushed by the person portraying a Secret Service agent. The person acting the role of Press Secretary James Brady (shot in the head), would fall to the ground. The person playing DC policeman Thomas Delahanty (shot in the neck) would fall forward.

Yes, we were aware on some level that our recess re-enactments of the Reagan assassination attempt were not “appropriate.” These were real people, wounded by real bullets. It was not something that we should be play-acting for fun.

So, why did we do it? Play is a way of understanding the world. Though horrific, the event was also so unreal (televised, rewound, repeated) that our improvised absurdist performances helped us make it real for ourselves. We were not merely making light of the darkness (though we were doing that, too); rather, our silliness was a way of understanding the seriousness.

My reaction to the murder of John Lennon was, I think, much closer to how people responded to President Kennedy’s murder. Neither of these were televised murders. (Jack Ruby’s murder of Lee Harvey Oswald happened on live TV, but the Zapruder film was not broadcast until the 1970s. While Lennon’s and Kennedy’s murder were both covered on TV, there was at the time no footage of the murders themselves.) The absence of the televisual made me feel Lennon’s murder more personally, more deeply –Â as did the fact that I was a fan of the Beatles. That was truly sad. The Reagan assassination attempt felt more surreal.

My reaction to the murder of John Lennon was, I think, much closer to how people responded to President Kennedy’s murder. Neither of these were televised murders. (Jack Ruby’s murder of Lee Harvey Oswald happened on live TV, but the Zapruder film was not broadcast until the 1970s. While Lennon’s and Kennedy’s murder were both covered on TV, there was at the time no footage of the murders themselves.) The absence of the televisual made me feel Lennon’s murder more personally, more deeply –Â as did the fact that I was a fan of the Beatles. That was truly sad. The Reagan assassination attempt felt more surreal.

The highly mediated world in which we now live affords us little time to actually feel the pain, much less think about it. In public places (at a school, in a movie theatre, in a store), the gunman — it is nearly always a man — fires. People flee, get maimed, die of their injuries. Survivors tell their stories to the media. Our legislators assure us that these murders are a byproduct of living in a free society; regulating guns would somehow make us (well, those of us not murdered by guns) less free. The sad inevitability of gun violence, offered up for our infotainment, impedes our ability to make sense of it.

But it’s not just media. Experience also dulls the senses. I felt more acutely Lennon’s murder precisely because I had no memory of the murders of Robert Kennedy, John F. Kennedy, or Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Its newness made its impact sharper.

Perhaps, then, that is one legacy of the Kennedy assassination. There were political murders before November 22 1963 (Presidents Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley were all assassinated), but in the years since that afternoon in Dallas, they seem to have become commonplace. And, as DeLillo has observed, “Our grip on reality has felt a little threatened.”

Above: Steinski’s “The Motorcade Sped On” (1986); video by Coldcut (2008).

Images: Zapruder film from Fans in a Flashbulb; Reagan assassination attempt from L.A. Times; Newsweek cover of Pope from eBay; Newsweek cover of John Lennon from The Pop History Dig.

Gwen Tarbox

Philip Nel

Gwen Tarbox

Philip Nel