Separating children from their parents is a violation of basic human rights and does not deter asylum-seekers. Hostile to facts and compassionate only towards himself, Mr. Trump has pursued this policy with reckless indifference to its consequences. As of the end of last month (over four months after the court-imposed deadline to reunite these families), over 140 children had still not been reunited with their parents. And that figure does not include the over 15,000 children locked up in Trump’s child detention centers.

Separating children from their parents is a violation of basic human rights and does not deter asylum-seekers. Hostile to facts and compassionate only towards himself, Mr. Trump has pursued this policy with reckless indifference to its consequences. As of the end of last month (over four months after the court-imposed deadline to reunite these families), over 140 children had still not been reunited with their parents. And that figure does not include the over 15,000 children locked up in Trump’s child detention centers.

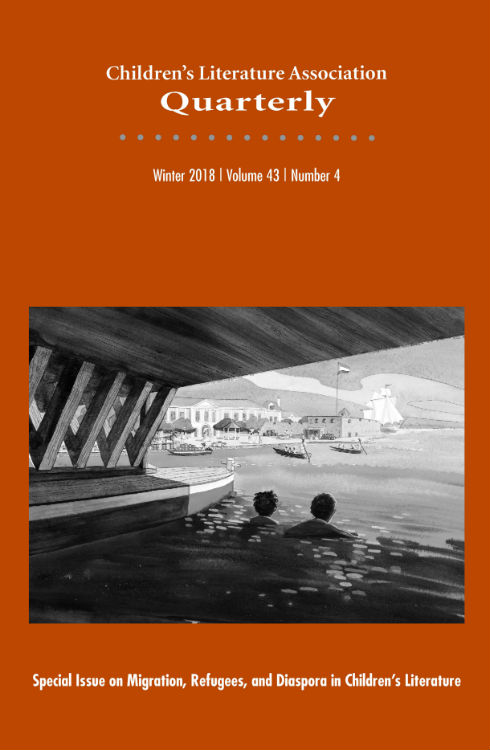

Writing about Migration, Refugees, and Diaspora in Children’s Literature – the theme of this special issue of the Children’s Literature Association Quarterly – will not stop the US government’s (or any other government’s) crimes against humanity. And yet, I edited this special issue, which features smart essays by six sharp scholars: Debra Dudek, Carmen Nolte-Odhiambo, Leyla Savsar, Anastasia Ulanowicz, Maria Rosa Truglio, and Sara Van den Bossche. Why? Not because we expect our words to awaken the consciences of those in power – if, indeed, the people who support these policies possess consciences. We write because we speak as we can, in the venues available to us. Because all scholarship is, in some measure, a record of the time in which it was written. Because children’s literature can cultivate empathy. Because children’s literature can (to borrow Rudine Sims Bishop’s famous term) serve as a mirror to young people who have been displaced – geographically, culturally, emotionally. Because words and images can change minds.

Or, at least, that is what I believe. As I write in my introduction,

When children’s literature cultivates an empathetic imagination, it can bring people of all ages closer to understanding the displacement felt by migrants, refugees, and those in diasporic communities. Such literature can affirm the experiences of children in those communities, letting them know that they are not alone….

As scholars of children’s literature, we are not, alas, in charge of shaping humane policies for our governments. But we can, to borrow the words of Russian-American journalist Masha Gessen, help people to envision “a world without borders as we have known them–a world in which nation-states are not prized or assumed.” We can guide readers to books that harness the imagination’s power to nourish empathy, and we can steer them away from those that reinforce bigotry. Thanks to our professional training, we understand that such work is necessary and complicated: A work’s propagation of prejudice can be both subtle and overt. Art is often ideologically ambivalent, humanizing in some ways and dehumanizing in others. Another thing we can do, then, is to teach people how to spot the difference. Careful, thoughtful readers can resist lies, misinformation, and scapegoating. By helping us develop the necessary critical literacies, the articles in this issue foster these vital skills.

The issue is available via ProjectMuse. If you are affiliated with an institution that subscribes to Project Muse, please access the articles that way. Doing so generates revenue for the Children’s Literature Association – an organization of which I am a member. If you lack access to the issue, I am glad to send you a pdf of my introduction. Just drop me a line. (Email address is at right, under “A note on mp3s,” even though I have long since removed mp3s from this blog.)

I’ll conclude with the two autobiographical paragraphs from my introduction:

I proposed this special issue, in part, because I am from a family of immigrants and am the descendant of refugees. The Nels were among those 2 million seventeenth-century French Protestants (Huguenots) whose flight from persecution introduced the word refugee into the English language. Today, my extended family (nuclear family plus cousins, uncles, and aunts) lives in five countries on four continents. We are a migratory group. In migrants, refugees, and the diasporic, I see my own family.

But I also see my family in the people who caused such displacement–from the active Islamophobe who supports a “Muslim ban” to the passive inheritors of White supremacy. I am aware that my being born in the US has everything to do with my parents being White South Africans and not Black South Africans. Their Whiteness granted them access not just to the education that made finding an American job possible, but also to the basic human rights that significantly increased the chances that they would survive and flourish. Indeed, my own flourishing is built upon a range of intersecting structures of oppression.

I’ve written more on this subject elsewhere on this blog – perhaps most directly in “Charleston, Family History, and White Responsibility” (June 2015). For the past few years, that post has only been available via its archival presence on the Wayback Machine, for reasons explained in the footnote below.* But there are plenty of other autobiographical posts hosted here, some of which address White Privilege and White Responsibility.

But,… returning to the special issue. Remember: human rights do not depend upon citizenship. Humanity has no borders.

Thanks to the editorial consultants for this issue: Evelyn Arizpe, Clare Bradford, Ann Gonzalez, Gabrielle Halko, Gillian Lathey, Kerry Mallan, Robyn McCallum, Mavis Reimer, Lara Saguisag, Lee Talley, Jan Van Coillie, Lies Wesseling

Other writing (by me) on this subject:

- Why Trump Jails Crying Children. How We Resist. (A Twitter Essay) (21 June 2018)

- Refugee Stories for Young Readers (Public Books, 23 Mar. 2017)

* My father was furious at me for speaking the truth. In an effort to keep the peace, I deleted the post (though, while writing this post now, have added a link from that post to the Wayback Machine’s archival record). This effort failed; dad stopped speaking to me shortly thereafter. Incidentally, ideas expressed in it emerge in Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature and the Need for Diverse Books (notably, the end of Chapter 3), but (unlike the original post) do so without identifying specific individuals.

W.B. Reeves

Philip Nel

Pingback: Interview | Philip Nel – Pine Reads Review