I added the quotation from Cage’s “Experimental Music” (1957).

1

There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear.

– John Cage, “Experimental Music” (1957), in Silence: 50th Anniversary Edition (Wesleyan UP, 2011), p. 8

Philip Nel, guitar and vocal, Manhattan, Kansas, 26 July 2020.

2 John Cage’s 4’33” was first performed by pianist David Tudor in Woodstock, New York, on 29 August 1952.

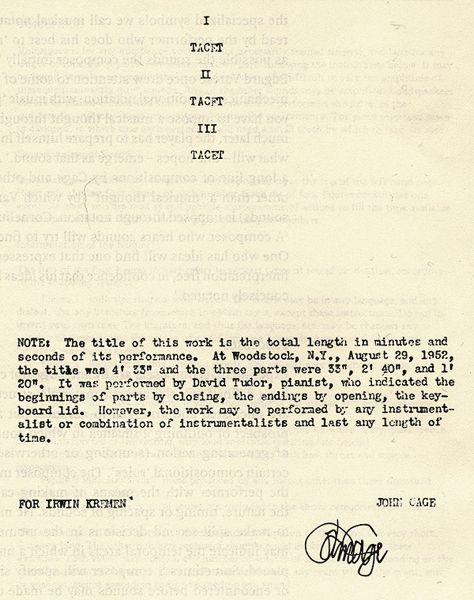

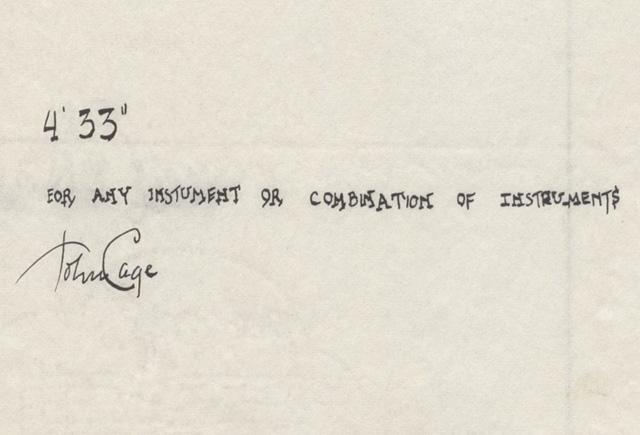

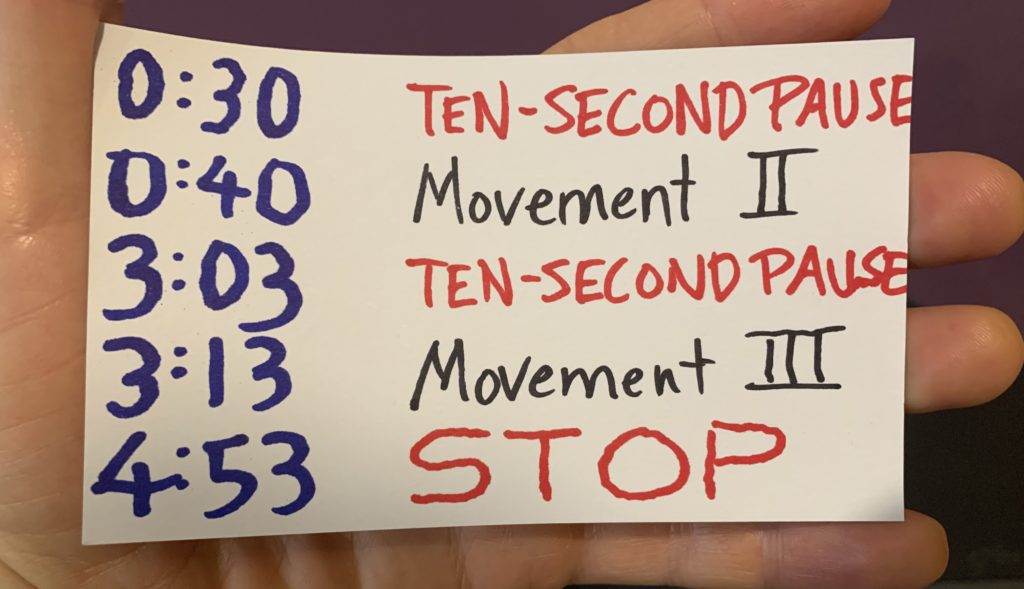

3 The piece has three movements, but their precise length can vary. According to the printed program for the 1952 Woodstock performance, the first movement is 30 seconds, the second 2 minutes and 23 seconds, and the third 1 minute and 40 seconds. That manuscript – which Cage gave to David Tudor – has been lost. In the First Tacet Edition manuscript of 1953, Cage says the first movement is 33 seconds, the second 2 minutes and 40 seconds, and the third 1 minute and 20 seconds. Cage’s note on that manuscript also tells us this: “It was performed by David Tudor, pianist, who indicated the beginnings of the parts by closing, the endings by opening, the key-board lid. However, the work may be performed any instrumentalist or combination of instrumentalists and last any length of time.”

4 I chose to perform the original Woodstock version because there’s the most textual evidence for that as the “original” version. Indeed, the Second Tacet Edition indicates that each movement was the length specified in the Woodstock program.

5 My decision is in some senses at odds with Cage’s aesthetic. He often used chance to make decisions about musical notes, the length of sounds, and the order in which to place them. I probably should have flipped a coin.

6 4’33” takes longer than four minutes and 33 seconds to perform. In between each movement, the performer typically pauses to signal one movement’s end and another’s beginning. I waited ten seconds between each movement, but one could of course wait for a longer or shorter duration. Arriving to play the piece creates a contrast between before the piece and during the piece; incorporating that helps create a visible “beginning” for an audience. So does having a conductor. Or opening and then closing the piano’s lid. But the performer needs to do something at both beginning and end to help the audience hear the start and conclusion of 4’33”. Indeed, it would be a challenge to perform 4’33” in less than five and a half minutes.

7

And what happens to a piece of music when it is purposelessly made? ¶What happens, for instance, to silence? That is, how does the mind’s perception of it change? Formerly, silence was the time lapse between sounds, useful towards a variety of ends, among them that of tasteful arrangement, where by separating two sounds or two groups of sounds their differences or relationship might receive emphasis; or that of expressivity, where silences in a musical discourse might provide pause or punctuation; or, again, that of architecture, where the introduction or interruption of silence might give definition either to a predetermined structure or to an organically developing one. Where none of these or other goals is present, silence becomes something else – not silence at all, but sounds, the ambient sounds. The nature of these is unpredictable and changing. These sounds (which are called silence only because they do not form part of a musical intention) may be depended upon to exist. The world teems with them, and is, in fact, at no point free of them.

– John Cage, “Composition as Process” (1958), in Silence: 50th Anniversary Edition (Wesleyan UP, 2011), pp. 22-23.

8 Each performance of 4’33” will be different because each silence is different. As Cage writes in the preceding quotation, when a piece of music does not use silence for structure or punctuation, “silence becomes something else – not silence at all, but sounds, the ambient sounds. The nature of these is unpredictable and changing.”

Kyle Shaw, piano, Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, Urbana, Ill., USA, 2016.

Orquesta Sinfónica del Conservatorio Nacional de Música, Quito, Ecuador, 2012.

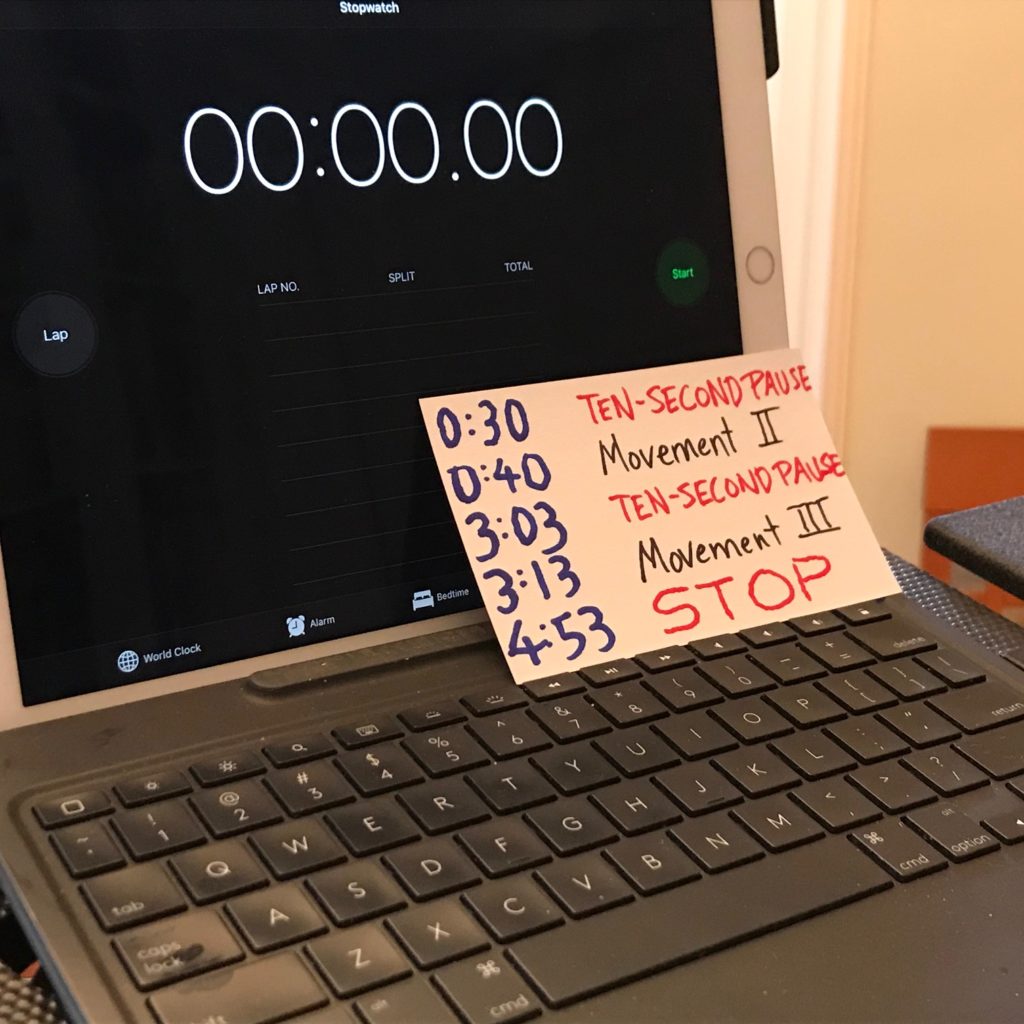

Dead Territory, Austria, 2015.

9 These are but some of the contemporary artists who have performed and recorded 4’33”: The Afghan Whigs, Depeche Mode, Erasure, Goldfrapp, Moby, New Order, Yann Tiersen, and Wire.

10 The 4’33” app for iPhone includes a performance recorded in Cage’s New York City apartment, and invites people to upload their own performances – which are then shared with all who have the app. In this way, it offers a variety of silences from around the world. All seven continents! Yes, including Antarctica.

11 I keep using the word silence, but 4’33” demonstrates the impossibility of silence. Cage often spoke of his visit to an anechoic chamber at Harvard University, in which he – alone in the chamber – was surprised to hear “two sounds, one high and one low.” Upon stepping out again, he asked the engineer about these sounds. As Cage recalled, the engineer told him that “the high one was my nervous system in operation, the low one my blood in circulation” (Cage 8).

12 4’33” is a plague song because the pandemic has changed our relationship to time, sound, and speech.

13 For those of us confined largely to the interior spaces of a home or apartment, time’s passage can no longer be measured according to the semi-regular rhythms supplied by a commute to work or a trip to the gym, nor via the changes introduced by travel to a conference (or for a holiday).

The Newzik Team, Paris, Marseille, and Tel Aviv, 1 April 2020.

Mondestrunken Ensemble, Kyiv, Ukraine, 4 April 2020.

14 We experience time differently in two dimensions (via Skype or Zoom) than we do in three dimensions (in person). One reason is the different relationship between time and space. Three-dimensional interpersonal intimacy has both simultaneity and physical proximity. Two-dimensional interpersonal intimacy has simultaneity without propinquity. To perhaps oversimplify, in 3-D interactions we have both time and space; in 2-D interactions we have time without space. As a result, we experience the temporal dimension differently.

15 Among my friends, we speak of the Before Times – prior to the pandemic. We also speak of another Before Times – prior to the 2016 US election. So, for example, February 2020 is in the Before Times. But February 2016 is two Before Times ago.

16 When I perform 4’33”, I focus more intently on keeping track of time: I want to pause at the right moment between movements, and think about how I want to (not) play the guitar for the next movement. For this performance, I even wrote out an index card so that I could see exactly when I should pause or begin a new movement.

17 In contrast to my experience of performing the piece, listening to 4’33 uncouples me from any particular relationship to time. My attention shifts to my environment, and I stop thinking about time. I think instead about sound, and notice all the ambient music I had missed.

18 During this pandemic, spending more time alone has sharpened my awareness of sound. The creak of the floor, the mechanical hum when the air-conditioning unit goes on, or the sound of a mower outside – all of these are more prominent in my life than they once were.

19 This change in ambient sound has become so acute that, during the NYC lockdown this spring, the New York Public Library produced an album called Missing Sounds of New York. Some of the tracks are “Serenity Is a Rowdy City Park” and “The Not-Quite-Quiet Library.” (For earlier examples of this sort of work, I highly recommend Millions of Musicians [1954] and other records in which Tony Schwartz recorded the voices and sounds from his environment.)

20 Music’s arrival into our more (though not completely) silent spaces has been especially powerful. Italians singing to each other from their balconies inspired me to begin this “Plague Songs” series back in mid-March. Music creates community, pushes back the loneliness that suffuses the now too-silent lives of those who live on their own, can no longer visit others with ease, or whose health requires that they isolate.

21 The pandemic has also called attention to a different kind of silence. In response to films of US police murdering African American citizens, people around the world have raised their voices to say Black Lives Matter. Astonishingly, in the US, this has happened in all fifty states – even in all-White towns. In response, the White-supremacist, fascist regime led by Donald Trump has been sending secret police to brutalize protesters. Predictably, his party has remained silent and thus complicit. However, protesters keep protesting, undeterred by these vicious, authoritarian displays of violence. Even though both COVID-19 and uniformed thugs threaten, Americans are fighting back. I find this hopeful.

22 Silence gives us time to reflect. I think the experience of being removed from one’s usual, hectic, daily life helped more White Americans truly see the brutality inflicted upon Americans of color. That, I think, is one reason why White people have joined the Black Lives Matter protests in far higher numbers than ever before.

23 In my Plague Diary for April 3rd, I wrote down this quotation:

Many of us have hugged loved ones for the last time, we just don’t know it yet.

It was tweeted on April 2nd by @ShotNoChaser on Twitter. Seeking to link to that Tweet here, I discovered that the account has disappeared.

24 Time is a recurring theme in my diary. I also noted this observation:

This is the lesson of the pandemic: we are now obligated to playact the standardized time that capitalism demands of us, now without any of the external social trappings. We are locked in a battle with the ticking clocks of our own emails and 9 AM Zoom meetings. Is it no wonder that so many of us feel that time is out of joint, when we are faced daily with the resounding contradiction between our clocks and our lived experience? Or that social unrest emerges in a moment when many have that most precious resource of all: free time?

– Jeffrey Moro, “Attack and Dethrone Time” (JeffreyMoro.com, 21 Jun. 2020)

25 Silence calls attention to who is silenced and who is heard. In The Memory Palace podcast’s episode #166 (“The Silent Room,” July 2020), Nate DiMeo reflects upon silence in music by pairing John Cage’s inspiration for 4’33” with how (White) history has kept silent the (African American) inspiration for Puccini’s Girl of the Golden West.

William Marx, piano, McCallum Theatre, Palm Desert, CA, USA, 2010.

26 The concert halls, the opera houses, the clubs, the venues where we hear music are all silent. Or, at least, it is not safe right now to hear music in the usual performance spaces. During this corona era, I find listening to live recordings more powerful than in the Before Times. Musicians gathered in a room, with an audience! Wow. I miss it, and as I listen, I can close my eyes and imagine myself in the crowd.

The Lockdown Nyckelharpa Orchestra, 1 May 2020.

27 I’ve enjoyed the music – recorded at a social distance – produced during the pandemic, though none of it could be live. It’s impossible to sync one Zoom call or live-stream with another. They’ll always be slightly out of alignment. Even a live-streamed show from a single musician only seems to be live. There’s actually a slight delay, creating a buffer so that – as all this data is transmitted – the video and audio do not freeze or skip.

28 That said, time and our experience of time are also slightly out of alignment.

29

Conscious thought – for instance, the determination of when ‘right now’ is – trails our physical experience very slightly. What we call reality is like one of those live, televised awards shows that has a brief delay built in in case someone curses.…

An event or an instant does not present itself to the brain a priori; it is not out there waiting to be noticed. Rather, it comes into being only after it is over, once the brain has paused to address and assemble it. “Now” only exists later – and only because you’ve stopped to declare it.

– Alan Burdick, Why Time Flies: A Mostly Scientific Investigation (2017)

30 I recorded 4’33” (and all the other songs in this series) in a single take because that was as close as I could get to a live performance. And I wanted to convey some of the connection you get with a live audience, even though there was no audience in the room with me.

31 Except for this one. Off screen, Karin started the timer (on an iPad) and so heard its full performance. (I recorded all other Plague Songs on a Monday, when she was working from her office and I was working from home.)

32 Though there are many recorded versions of 4’33”, I want to argue that it should be heard live. Being in the space of its performance is, I think, part of the experience of Cage’s piece.

Lito Levenbach, 15 instruments (banjo, accordion, electric guitar, ukulele, mandolin, tambourine, kazoo, shaker, piano, lap steel guitar, ocarina, drums, bass guitar, acoustic guitar, harmonica), Netherlands, 2015.

33 That said, all of the versions I’ve shared here are (obviously) already recorded. Indeed, I have never heard 4’33” live myself – except for my own performances of it. Yes. Performances. Plural. As has been the case with all songs in this series, I practiced Cage’s piece.

34 In some respects, not playing a guitar takes more effort than playing a guitar. I had to remember both to avoid strumming and to hold my fingers above the strings, but not on them. Indeed, the version I have shared above is the second take. In the first, I accidentally touched a string between the second and third movements. Since it was between movements, I could have left it as part of the performance or I could have edited out that tiny piece of audio. But I wanted unadulterated footage, and I wanted to not play. So, I did a second take.

35 Try performing 4’33” yourself. Try it on whatever instrument or instruments you play. If you don’t play an instrument, then use your voice. How will you not play or not sing? What will you do to signal each movement? (Or will you?) Which version of the piece will you perform? Will you accept Cage’s invitation to make your version “last any length of time”?

36 I sometimes joke that my most frequently requested song is 4’33” – a self-deprecating acknowledgment of my limitations as a guitarist and singer.

37 Others have also used the piece as a joke, as for example when Stephen Colbert had NOLA the cat perform it.

NOLA the Cat, vocal, 2015.

38 4’33” is funny, but its humor is also more than a joke. Seeing a musician or musicians arrive on stage and then not play is humorous, but once the piece begins so do the provocations of that humor. What is music? Does music require notes performed by a musician, in a particular sequence? Is there (as John Cage believed) music all around us, if only we would take notice of it?

39 4’33 uses humor in the way that Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings (1953-1967) do. Reinhardt and Cage defy our expectations, asking us what is art? They ask us to pay attention. They invite us to meditate, to reflect, to reckon with ourselves.

40 Cage’s 4’33” and Reinhardt’s black paintings are, in this sense, deeply spiritual works. They offer us the stillness in which to meditate. The Japanese word Zen – a big influence on Cage – means meditation.

41

In Zen they say: If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, try it for eight, sixteen, thirty-two, and so on. Eventually one discovers that it’s not boring at all but very interesting.

– John Cage, in Silence: 50th Anniversary Edition (Wesleyan UP, 2011), p. 69

42

Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.

[L’attention est la forme la plus rare et la plus pure de la générosité.]

–Simone Weil, letter to Joë Bousquet, 13 April 1942 (Correspondance [1982], p. 18)

43

Thank you for your time and attention.

– announcement made in U.S. movie theaters, just prior to first “coming attractions” trailer

David Tudor, piano, date unknown.

“I HAVE NOTHING TO SAY AND I AM SAYING IT.”

– John Cage, “Composition as Process” (1958), in Silence: 50th Anniversary Edition (Wesleyan UP, 2011), p. 51

You could perform a #PlagueSong, too. I’ve many ideas on this playlist. But I know there are many more I’ve not considered. Or, of course, you could remain silent.

Related Posts

- Avant-Garde

- It Looks Like Snow (9 Mar. 2011). Remy Charlip’s picture-book tribute to John Cage.

- This Is Not a Muppet: Jim Henson, Avant-Garde Filmmaker (1 Dec. 2013)

- Avant-Garde Children’s Books; or, What I Learned in Sweden Last Week (5 Oct. 2015)

- Ruth Krauss, Sergio Ruzzier, and… the Beatles? (17 Oct. 2019)

- Plague Songs

- Sing. Sing a Song. #PlagueSongs, no. 1 (17 Mar. 2020). Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive.”

- Do Not Touch Your Face. #PlagueSongs, no. 2 (24 Mar. 2020). The Weeknd’s “I Can’t Feel My Face.”

- The Bright Side. #PlagueSongs, no. 3 (31 Mar. 2020). Monty Python’s “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.” Also the first post where I began my practice of using a lyric as the title.

- It’s later than you think. #PlagueSongs, no. 4 (7 Apr. 2020). Prince Buster’s “Enjoy Yourself.” (Also: the discovery that I cannot play ska.)

- There doesn’t seem to be anyone around. #PlagueSongs, no. 5 (14 Apr. 2020). Tommy James and the Shondells’ “I Think We’re Alone Now.”

- Be an optimist instead. #PlagueSongs, no. 6 (21 Apr. 2020). The Kinks’ “Better Things.”

- Kick at the darkness. #PlagueSongs, no. 7 (28 Apr. 2020). Bruce Cockburn’s “Lovers in a Dangerous Time.”

- So far away, but still so near. #PlagueSongs, no. 8 (5 May 2020). Robyn’s “Dancing on My Own.”

- If you just call me. #PlagueSongs, no. 9 (12 May 2020). Bill Withers’ “Lean on Me.”

- In the end, they’ll be the only ones there. #PlagueSongs, no. 10 (19 May 2020). Hanson’s “MMMBop,” and a few chords from Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

- No matter how I struggle and strive. #PlagueSongs, no. 11 (25 May 2020). Hank Williams’ “I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive.”

- Love. #PlagueSongs, no. 12 (1 June 2020). Medley of Nick Lowe’s “(What’s so Funny ‘Bout) Peace Love, and Understanding” and the O’Jays’ “Love Train,” with brief snippets of the Staple Singers’ “This Train” and the Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love.”

- This is the time. #PlagueSongs, no. 13 (9 June 2020). Lou Reed’s “There Is No Time.”

- My neighbor and my friend. #PlagueSongs, no. 14 (16 June 2020). Fred Rogers’ “Won’t You Be My Neighbor.”

- If you’re lost, I’m right behind. #PlagueSongs, no. 15 (23 June 2020). Everything But the Girl’s “We Walk the Same Line.”

- Live to see another day. #PlagueSongs, no. 16 (30 June 2020). The Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive.”

- Offer me solutions, offer me alternatives, and I decline. #PlagueSongs, no. 17 (7 July 2020). R.E.M.’s “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine).”

- Someday we’ll find it. #PlagueSongs, no. 18 (14 July 2020). Kermit the Frog’s “Rainbow Connection.”

- Can’t control my brain. #PlagueSongs, no. 19 (21 July 2020). Ramones’ “I Wanna Be Sedated.”

- What Is Your COVID-19 Routine?

- What Is Your COVID-19 Routine? (22 Mar. 2020)

- What Is Your COVID-19 Routine? Part 2 (5 Apr. 2020)

- What Is Your COVID-19 Routine? Part 3 (19 Apr. 2020)

- What Is Your COVID-19 Routine? Part 4 (16 May 2020)

- What Is Your COVID-19 Routine? Part 5 (29 June 2020)

Lia

Philip Nel

Lia

Philip Nel