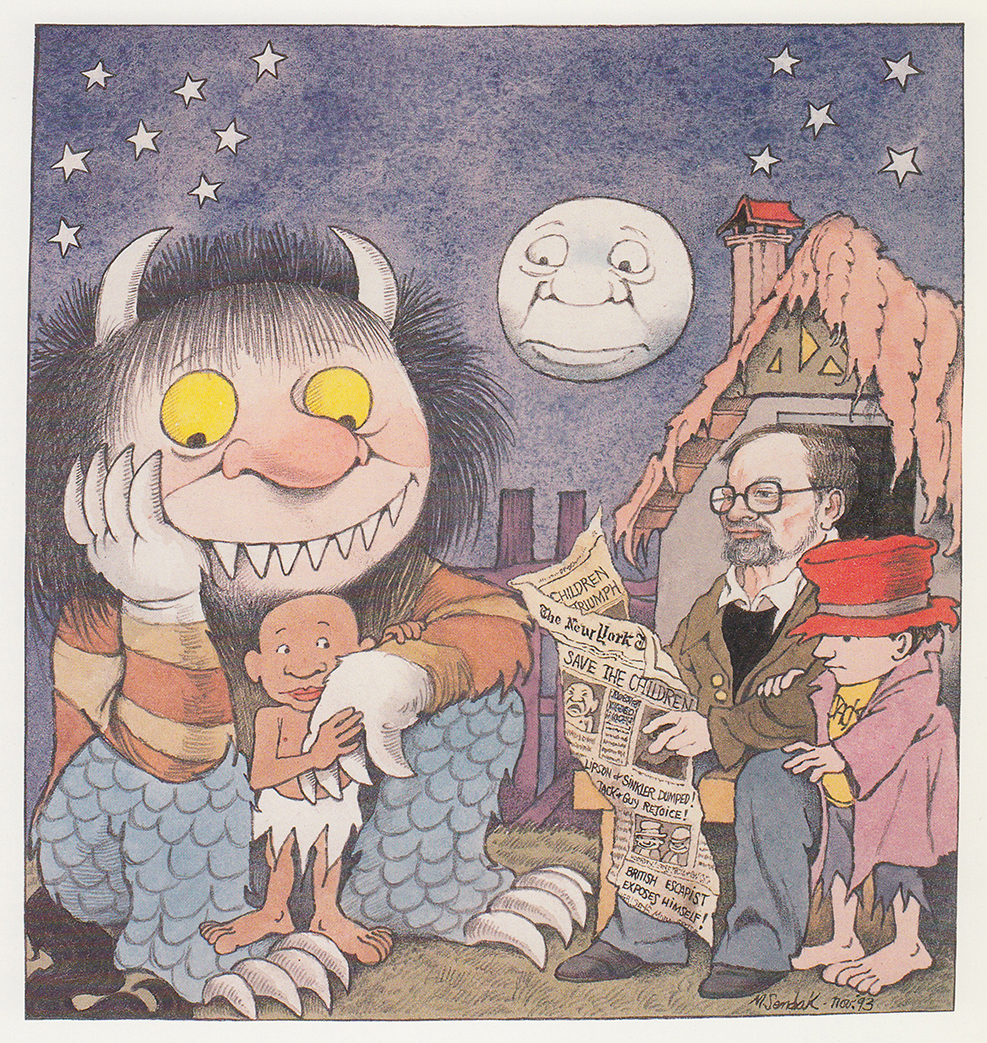

Wills offer unique insights into people’s lives – what they value most, how they see themselves, how they hope to be remembered. Ruth Krauss left most of her estate to homeless children, a fact which floored Maurice Sendak, when I told him: she died the same year that We’re All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy, Sendak’s book about homeless children, was published. Today, on what would have been Maurice Sendak’s 87th birthday, here is his will (click for a pdf).

And here is my inevitably subjective interpretation of what this 22-page document tells us about Maurice Sendak. If the named items in his collection of manuscripts, letters, toys, and ephemera tell us which literary and cultural figures were dearest to him, then those figures are:

- Beatrix Potter

- Mickey Mouse

- Herman Melville

- Henry James

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

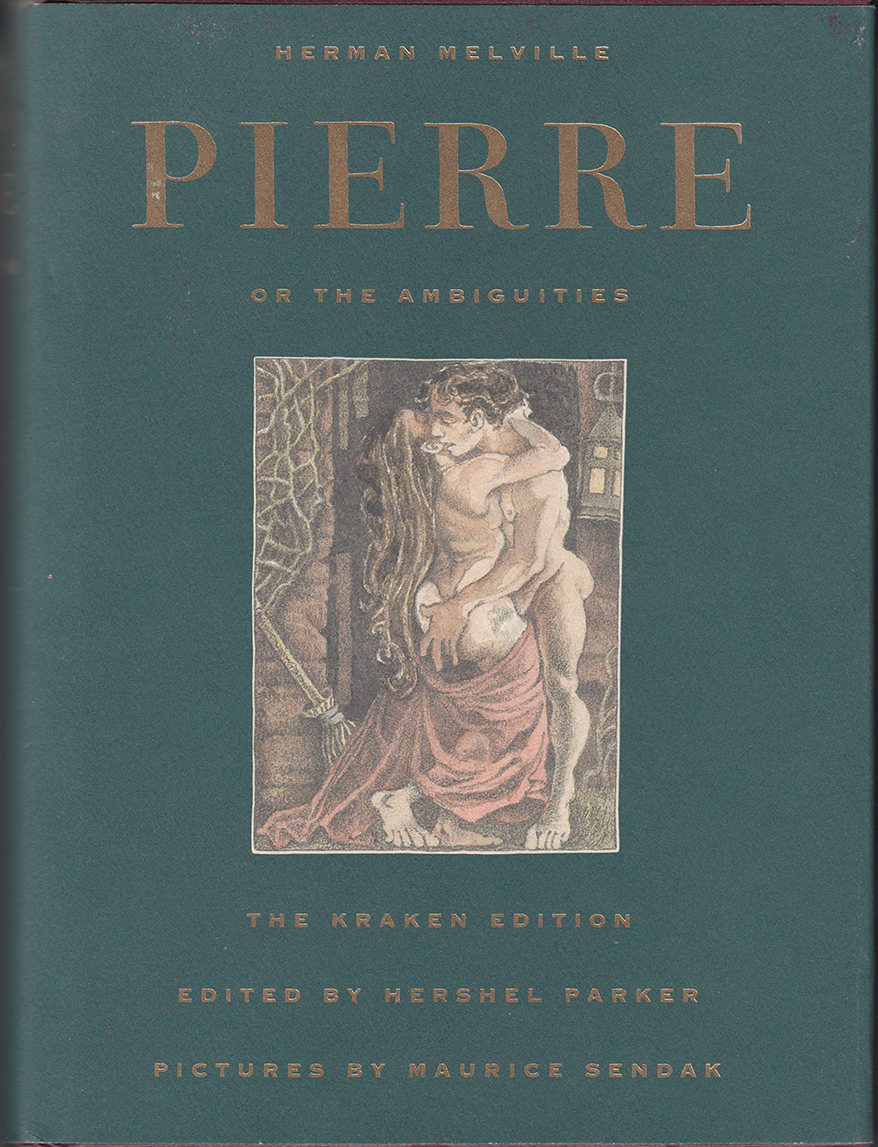

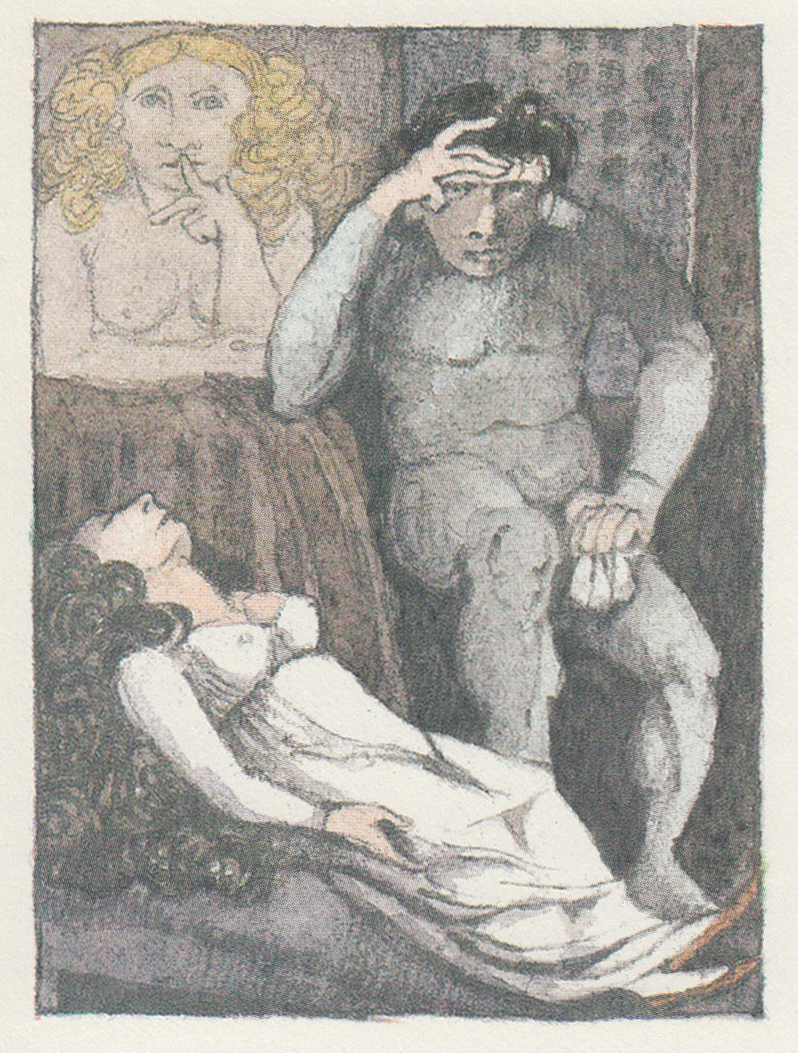

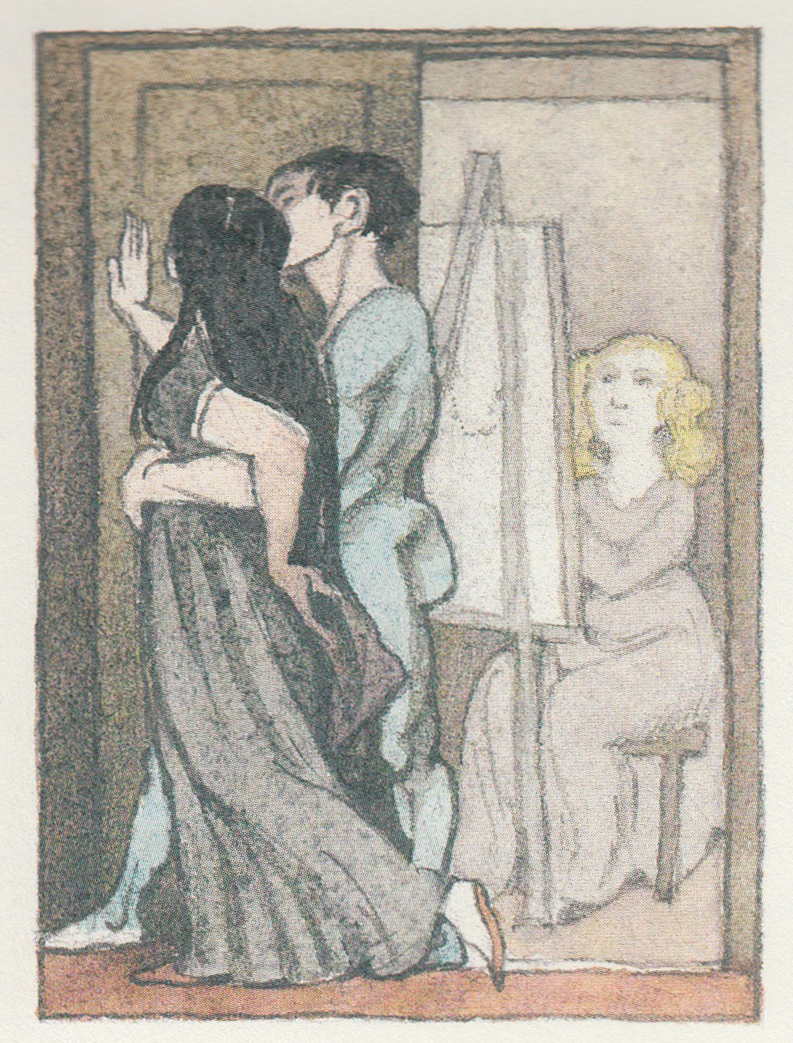

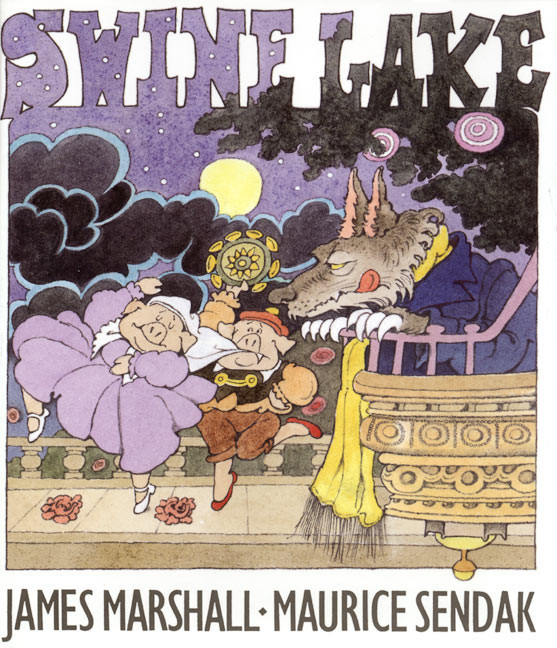

- James Marshall

But especially Herman Melville, who is named three times. To the Rosenbach Museum and Library, Sendak gives all of his “rare edition books, including, without limitation, books written by Herman Melville and Henry James” (2), and his “collection of letters and manuscripts written by persons other than [him], including, without limitation, letters written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (also known as the Brothers Grimm) and Herman Melville; and the publishing contract for ‘Pierre’ between Herman Melville and Harper and Brothers Publisher” (3). His affection for all of these figures is well known. In 1995, he even did an illustrated edition of Pierre, dedicating the pictures “in remembrance of” his brother Jack, who died earlier that same year. What fascinates me is that he so loved the novel that he obtained a copy of Melville’s contract with Harper and Brothers.

But especially Herman Melville, who is named three times. To the Rosenbach Museum and Library, Sendak gives all of his “rare edition books, including, without limitation, books written by Herman Melville and Henry James” (2), and his “collection of letters and manuscripts written by persons other than [him], including, without limitation, letters written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (also known as the Brothers Grimm) and Herman Melville; and the publishing contract for ‘Pierre’ between Herman Melville and Harper and Brothers Publisher” (3). His affection for all of these figures is well known. In 1995, he even did an illustrated edition of Pierre, dedicating the pictures “in remembrance of” his brother Jack, who died earlier that same year. What fascinates me is that he so loved the novel that he obtained a copy of Melville’s contract with Harper and Brothers.

|

![Sendak, Melville's Pierre: [untitled]](https://philnel.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/sendak_pierre2_w.jpg) |

|

|

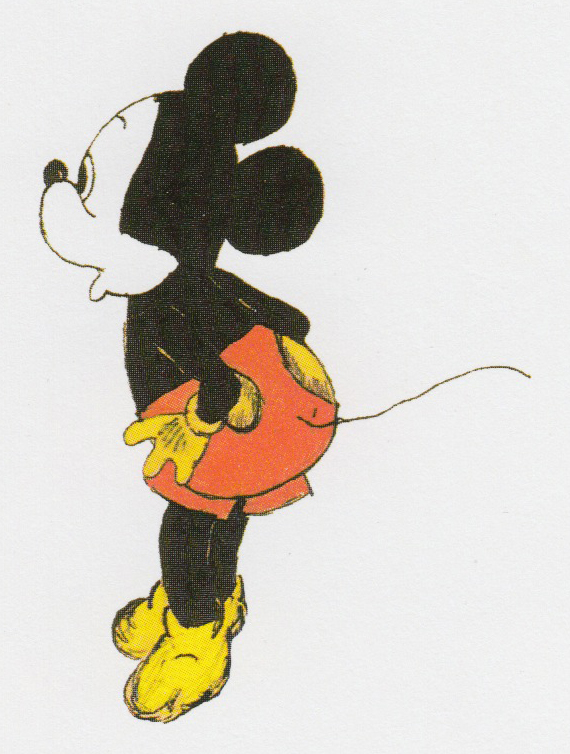

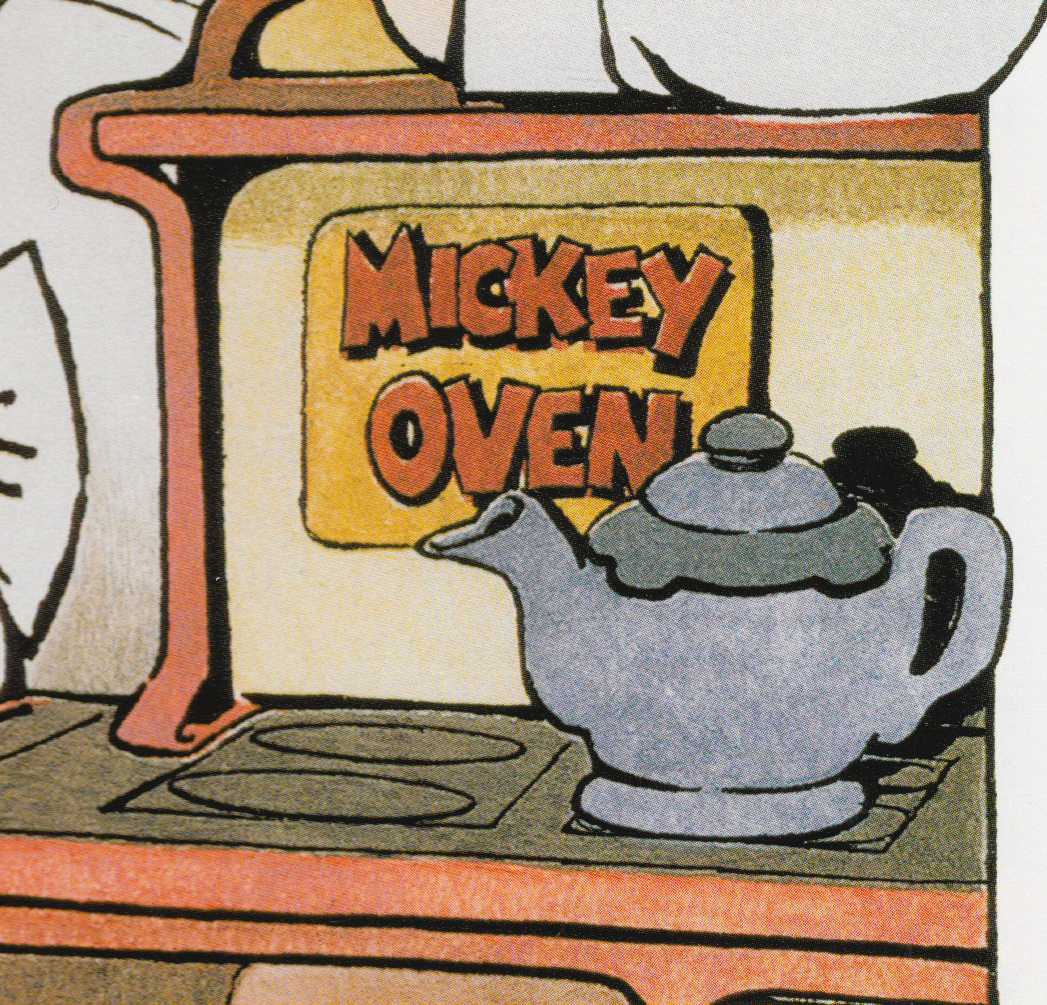

Sendak’s love for Mickey Mouse is also no secret. He named the protagonist  of In the Night Kitchen “Mickey” after the mouse (and because “M” is Sendak’s own first initial), and painted that book’s “Mickey Oven” in the red of Mickey’s shorts and yellow of Mickey’s shoes. (Originally, he’d wanted to use an image of Mickey, but Disney refused to grant permission.) Sendak’s earliest surviving drawing (from 1934, the year he turned 6) is of Mickey Mouse. So, Mickey’s appearance in the will is more confirmation than revelation. Still, though, it is the first item he lists among those going to the Rosenbach: “Such articles of my Mickey Mouse collection as my executors, in their sole and absolute discretion shall select” (2). He then directs that “the remaining balance of [his] Mickey Mouse collection” go to the Maurice Sendak Foundation, Inc.

of In the Night Kitchen “Mickey” after the mouse (and because “M” is Sendak’s own first initial), and painted that book’s “Mickey Oven” in the red of Mickey’s shorts and yellow of Mickey’s shoes. (Originally, he’d wanted to use an image of Mickey, but Disney refused to grant permission.) Sendak’s earliest surviving drawing (from 1934, the year he turned 6) is of Mickey Mouse. So, Mickey’s appearance in the will is more confirmation than revelation. Still, though, it is the first item he lists among those going to the Rosenbach: “Such articles of my Mickey Mouse collection as my executors, in their sole and absolute discretion shall select” (2). He then directs that “the remaining balance of [his] Mickey Mouse collection” go to the Maurice Sendak Foundation, Inc.

Suggesting that he wanted to help scholars study the works of those he collected, Sendak also took care to locate like materials together. When I interviewed him back in June 2001, he fretted over whether work related to his collaborations with Ruth Krauss should go with the rest of his materials or to the University of Connecticut at Storrs, where her papers are. In that conversation, he concluded that the Krauss work should go to Storrs. The will  indicates either that he changed his mind or forgot this earlier decision, but he does remember to send “all of [his] collections of books and related papers, drawings, works of art and letters created by James Marshall” to Storrs. He also gives his “two (2) walking sticks that previously belonged to Beatrix Potter and William Heelis” to the Beatrix Potter Society in London.

indicates either that he changed his mind or forgot this earlier decision, but he does remember to send “all of [his] collections of books and related papers, drawings, works of art and letters created by James Marshall” to Storrs. He also gives his “two (2) walking sticks that previously belonged to Beatrix Potter and William Heelis” to the Beatrix Potter Society in London.

There’s something about these physical objects that captures the imagination – Maurice Sendak with Beatrix Potter’s walking sticks! Maurice Sendak with original letters from Mozart, Melville, and the Brothers Grimm! Maurice Sendak with vintage Mickey Mouse toys! What we collect reflects who we are. The books on the shelves, the art on the wall, and the saved childhood memorabilia all offer a glimpse into a person’s interior life. When I think of these things that were dear to him, I imagine him at home, contemplating his collection. I also wish I’d taken him up on the invitation to visit, but I was then too shy, too intimidated by the idea. (Visit the great Maurice Sendak? At his home? Me? Uh….).

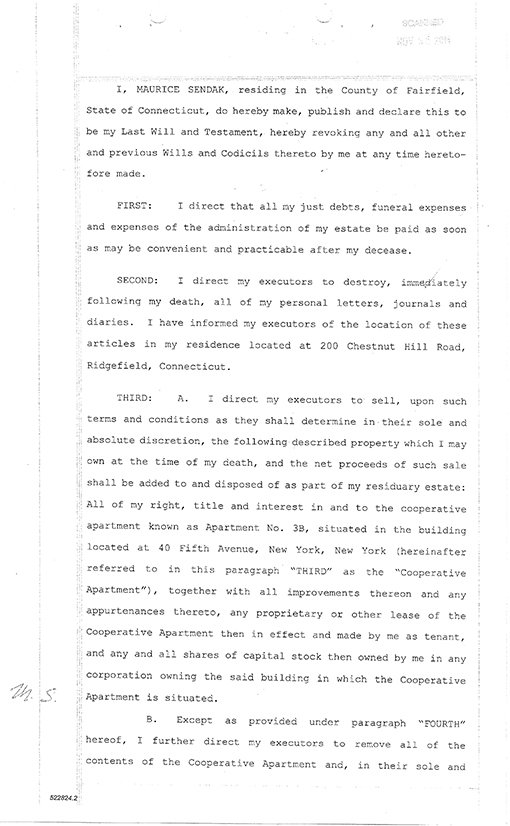

His will suggests that, if we are to catch sight of Sendak’s inner life, we will have to glean it from his works and from the works of those he collected. The second item on the will’s first page orders the destruction of his personal papers: “I direct my executors to destroy, immediately following my death, all of my personal letters, journals and diaries” (1). As a biographer, I feel a pang of loss at this sentence – what insights these materials would have offered! But I am not writing Sendak’s biography. And whoever does will have plenty to work with. In addition to being a public figure (many interviews!), Sendak collected his non-fiction in Caldecott & Co. (1988), worked with Selma Lanes on The Art of Maurice Sendak (1980) and with Tony Kushner on The Art of Maurice Sendak Since 1980 (2003). All three of these works are partly biographical. Adding to that record, next year will mark the appearance of Peter Kunze’s Conversations with Maurice Sendak, which includes – for the first time – my 2001 interview.

His will suggests that, if we are to catch sight of Sendak’s inner life, we will have to glean it from his works and from the works of those he collected. The second item on the will’s first page orders the destruction of his personal papers: “I direct my executors to destroy, immediately following my death, all of my personal letters, journals and diaries” (1). As a biographer, I feel a pang of loss at this sentence – what insights these materials would have offered! But I am not writing Sendak’s biography. And whoever does will have plenty to work with. In addition to being a public figure (many interviews!), Sendak collected his non-fiction in Caldecott & Co. (1988), worked with Selma Lanes on The Art of Maurice Sendak (1980) and with Tony Kushner on The Art of Maurice Sendak Since 1980 (2003). All three of these works are partly biographical. Adding to that record, next year will mark the appearance of Peter Kunze’s Conversations with Maurice Sendak, which includes – for the first time – my 2001 interview.

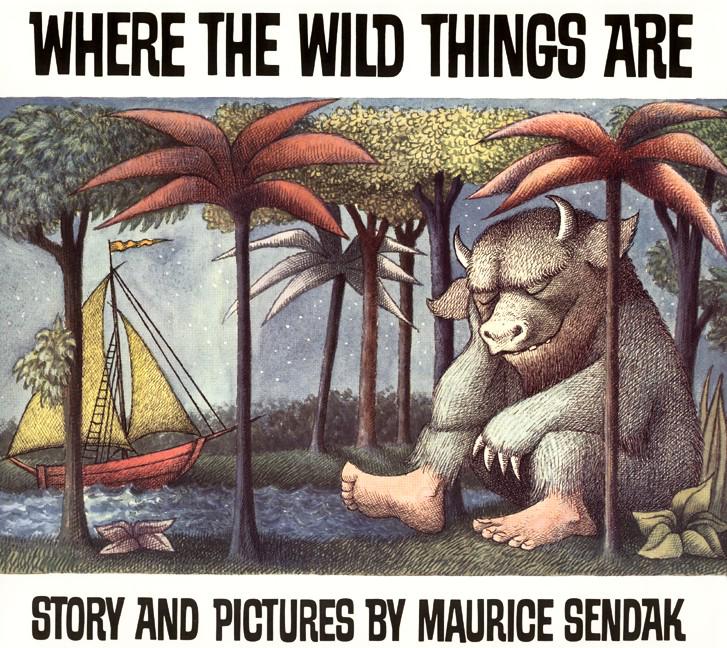

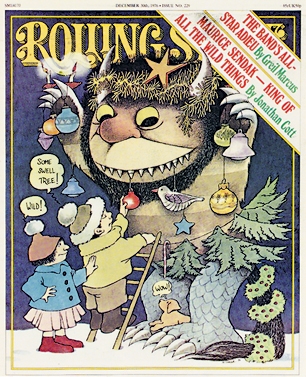

I remember Sendak once saying, somewhat ruefully, that Where the Wild Things Are would be in the first line of his obituary. He was proud of the book, but he did so much more, and hoped people would recognize his larger body of work. As if to aid in that recognition, Sendak leaves his original works in libraries where others can study them. He gives his “designs of sets and costumes for operas, plays and ballets” to the Pierpont Morgan Library (2). To the Maurice Sendak Foundation, he bequeaths “All the works of art created by me for my books and all materials related thereto, including, without limitation, manuscripts, dummies, sketches of and for my books, changes to and proof sheets for my books, and all related ephemera” (5). Indicating that Sendak wants scholars to have access, he asks that the Maurice Sendak Foundation “make arrangements with the Rosenbach Museum and Library for the display” of these items. Indeed, he specifically asks the Maurice Sendak Foundation to use his house “as a museum or similar facility, to be used by scholars, students, artists, illustrators and writers, and to be opened to the general public” (4-5).

I remember Sendak once saying, somewhat ruefully, that Where the Wild Things Are would be in the first line of his obituary. He was proud of the book, but he did so much more, and hoped people would recognize his larger body of work. As if to aid in that recognition, Sendak leaves his original works in libraries where others can study them. He gives his “designs of sets and costumes for operas, plays and ballets” to the Pierpont Morgan Library (2). To the Maurice Sendak Foundation, he bequeaths “All the works of art created by me for my books and all materials related thereto, including, without limitation, manuscripts, dummies, sketches of and for my books, changes to and proof sheets for my books, and all related ephemera” (5). Indicating that Sendak wants scholars to have access, he asks that the Maurice Sendak Foundation “make arrangements with the Rosenbach Museum and Library for the display” of these items. Indeed, he specifically asks the Maurice Sendak Foundation to use his house “as a museum or similar facility, to be used by scholars, students, artists, illustrators and writers, and to be opened to the general public” (4-5).

As you probably already know, the question of which materials go where is the subject of a lawsuit. (The Rosenbach Museum is suing the Sendak Foundation.) I won’t speculate on that dispute here, but I will say that authors’ and artists’ legal legacies are intriguing. Since wills and lawsuits are a matter of public record, they’re also available for our consideration. Indeed, though I don’t have the time to pursue this, someone should edit an essay collection titled In the Event of My Death: The Legal and Literary Afterlives of the Great Children’s Writers. In addition to authors’ and artists’ wills, there are other notable legal battles, such as those between A.A. Milne’s heirs and the Walt Disney Company, or Dr. Seuss Enterprises vs. Penguin Books (1997).

As you probably already know, the question of which materials go where is the subject of a lawsuit. (The Rosenbach Museum is suing the Sendak Foundation.) I won’t speculate on that dispute here, but I will say that authors’ and artists’ legal legacies are intriguing. Since wills and lawsuits are a matter of public record, they’re also available for our consideration. Indeed, though I don’t have the time to pursue this, someone should edit an essay collection titled In the Event of My Death: The Legal and Literary Afterlives of the Great Children’s Writers. In addition to authors’ and artists’ wills, there are other notable legal battles, such as those between A.A. Milne’s heirs and the Walt Disney Company, or Dr. Seuss Enterprises vs. Penguin Books (1997).

Posthumous lawsuits tell us as much about the artist’s friends and advisors as they do about the artist. But the will displays what and who was most important to the late artist. In this brief, speculative essay, I’ve focused more on the what than the who, but – as you’ll see, if you read the will – the who for Maurice Sendak is clear. It’s Lynn Caponera, Sendak’s caretaker and friend and, today, one of the executors of his estate. What’s so wonderful about Sendak’s will is that he remembers not just the friends and family who were dear to him, but all of us who care about art. So, on his birthday, I’ll add my thanks to a great artist not just for leaving a rich legacy, but for envisioning a future in which his own legacy can be appreciated and studied.

Further reading on Maurice Sendak (mostly on this blog):

- “It’s a Wild World: Maurice Sendak, Wild Things, and Childhood” (15 Oct. 2013). The “unpublished” parts of my PMLA essay… published as an essay of their own! Bonus: links to Sendak posts by fellow Niblings Betsy Bird, Julie Walker Danielson, & Travis Jonker.

- “Sendak on Sendak” (9 July 2013): video of Sendak interviews, and select quotations from print Sendak interviews.

- “Annotating My Brother’s Book: Some initial thoughts on Sendak’s use of Blake’s pictorial language. A guest post by Mark Crosby” (9 March 2013). Blake scholar Mark Crosby shows us how Blake’s work illuminates My Brother’s Book.

- “The Most Wild Thing of All: Maurice Sendak, 1928-2012” (9 May 2012). My tribute to Sendak, including extracts from an (otherwise unpublished) interview I did with him, back in 2001. At the bottom of the post: links to many other tributes and obituaries from around the web.

- “The King of the Wild Things Is Dead. Long Live the King. Maurice Sendak (1928-2012)”. My obituary for Sendak, which ran in the Comics Journal. A longer version appears as the introduction to Gary Groth’s interview, in the latest print issue.

- “Tributes to Maurice Sendak: Artists Respond” (11 May 2012). In the wake of Sendak’s passing, many people created visual tributes. These are a few.

- “Maurice Sendak, 1928-2012”. The Horn Book‘s tribute includes links to interviews and articles.

- “Eat, Drink, and Be Merry” (8 Oct. 2011). My review of Sendak’s Bumble-Ardy.

- “Maurice Sendak, Uncensored” (23 Feb. 2013). A few thoughts on (and quotations from) Gary Groth’s Comics Journal interview.

- “In or Out?: Crockett Johnson, Ruth Krauss, Sexuality, Biography” (17 Feb. 2011). In which I meditate on how to address (or not) Maurice Sendak’s sexuality in my biography of Johnson and Krauss.

- The Maurice Sendak tag will take you to other posts on this blog.

Image credits: Maurice Sendak, “Northeast cover” (Hartford Courant Sunday Magazine, 19 Dec. 1993) from Sendak in Asia: Exhibition and Sale of Original Artwork (1996); Sendak, cover and four illustrations from Herman Melville’s Pierre or the Ambiguities (The Kraken Edition, 1995); Sendak’s earliest extant drawing (Mickey Mouse, 1934) from Selma G. Lanes, The Art of Maurice Sendak (1980); Sendak Sendak, detail from Mickey Oven, In the Night Kitchen (1970); James Marshall and Maurice Sendak, Swine Lake (1999); first page of Maurice Sendak’s will (2011), courtesy of probate court in Bethel, Connecticut; Sendak, Where the Wild Things Are (1963); Sendak, cover for Rolling Stone (30. Dec. 1976).

Thanks to Sara & David Austin for sending the will, and of course to the probate court in Bethel, Connecticut, for providing access to it.

Jessica Boehman

Philip Nel

Leda