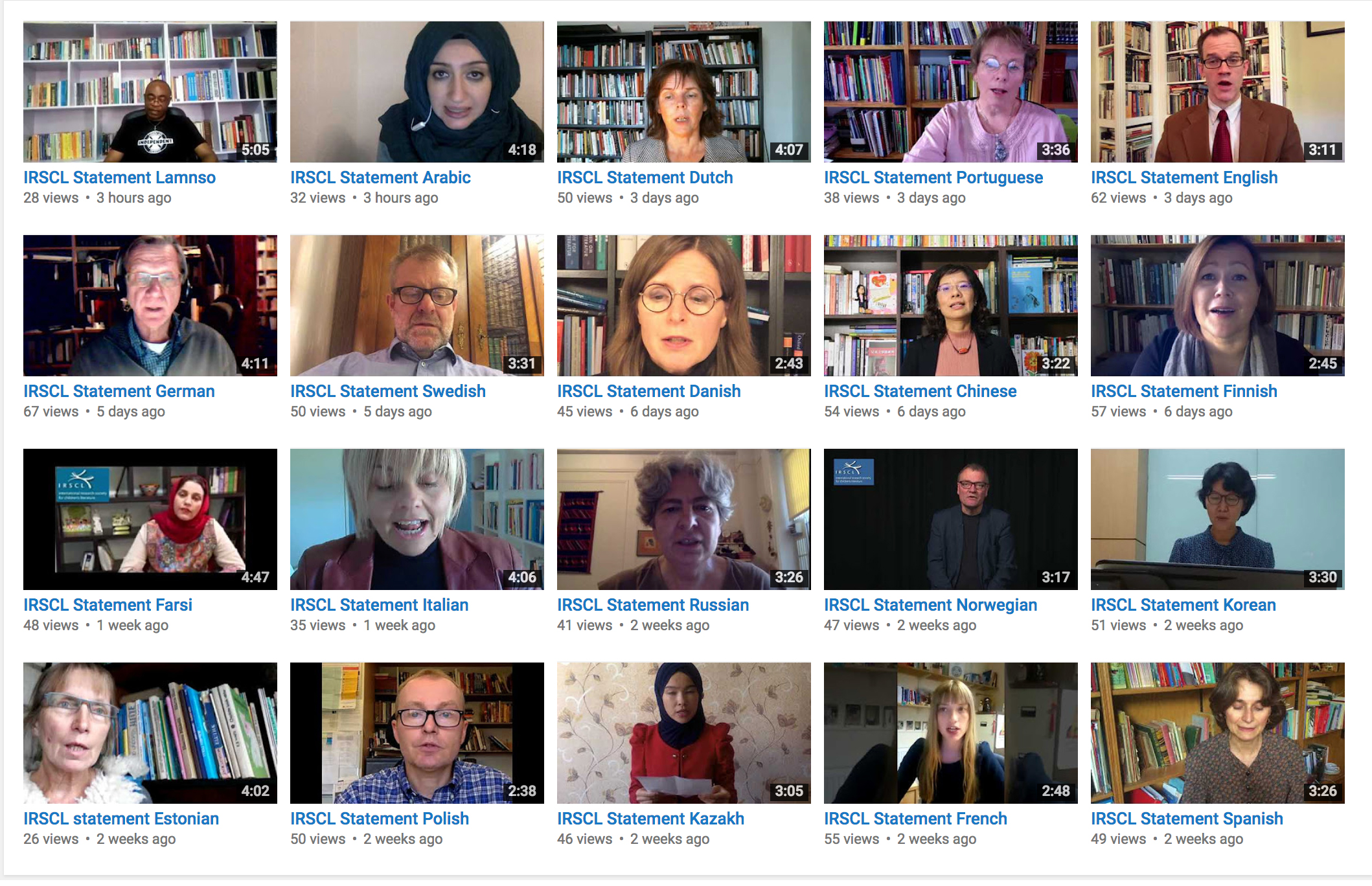

The International Research Society for Children’s Literature (IRSCL) – an organization of which I am a member – is today issuing a statement in support of academic freedom, and against the rising tide of nativism/nationalism that threatens to curtail it. We’re issuing it in 20 different languages (with more to come) and you can see all of those on our YouTube channel: Arabic, Chinese, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Farsi, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Kazakh, Korean, Lamnso, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, and Swedish. Coming soon (we hope): Japanese and others.

30 Nov. 2017: added Ukranian, updated link to Danish.

I concede that our language may be a little too “academic,” but consider that we coordinated this across borders, languages, holiday calendars, and extremely busy schedules. And it’s important to speak up for our shared humanity, for a scholarly community that transcend national borders, for free and open inquiry.

- YouTube channel with all the videos

- Facebook event page

- The press release in English (below) –

- The press release in many other languages via this sentence (pdf).

Press Release: Current Global Politics Limit Academic Freedom

On Universal Children’s Day, November 20, 2017, the International Research Society for Children’s Literature (IRSCL) issues a Statement of Principles, because it is worried about the ways in which contemporary geopolitics curtail academic freedom.

On Universal Children’s Day, November 20, 2017, the International Research Society for Children’s Literature (IRSCL) issues a Statement of Principles, because it is worried about the ways in which contemporary geopolitics curtail academic freedom.

This summer, IRSCL convened its 23rd biennial congress in Canada. More than 20 percent of the scholars whose papers were accepted were unable to attend Congress 2017, not only because of radical economic disparities in the world but also because of current restrictive travel policies and the “chill” caused by them.

- IRSCL finds the current xenophobic situation worrying as it curtails academic freedom. The free flow of people and ideas across borders has to be defended anew, says Elisabeth Wesseling, President of IRSCL.

For this reason, IRSCL will issue a Statement of Principles, which explains why scholarship can flourish only in a world with open borders. The statement will be released as a collection of videos featuring IRSCL members reading the statement in their native language - the statement is issued on November 20, Universal Children’s Day, to emphasize not only the importance of our research, but also of children’s literature’s potential to foster empathy, nurture creativity, and imagine a better world, says Elisabeth Wesseling.

IRSCL is an international scholarly organization dedicated to children’s and young adult literature with 360 members from 47 different countries worldwide. Every second year the organization arranges IRSCL Congress, the world’s most international congress within the research field.

Professor Elisabeth Wesseling (Lies.Wesseling@Maastrichtuniversity.nl), President, IRSCL

Videos of IRSCL members reading the statement in 18 languages

(These are also available en masse via our YouTube channel.)

Yes, that’s me reading it in English. (I’m one of the statement’s many co-writers. )

Arabic

Chinese

Danish

Dutch

English

Estonian

Farsi

Finnish

French

German

Italian

Kazakh

Korean

Lamnso

Norwegian

Polish

Russian

Spanish

Swedish

Ukranian

In reading the statement (above) and writing this little blog post, I’m proud to stand with my friends and colleagues around the world. And I’m especially delighted to see them speaking their native languages. When we meet, we converse in English – because English is the “international” language of communication among scholars. So, English-speakers like me have it easy: everyone else speaks my language. But for everyone else, this is of course grossly unfair. I am grateful to them for learning English so that we can share ideas, and participate in a global community. And I thank them for tolerating my general inability to speak their languages.

Reading children’s books about all different people (all types of difference, though in this case, national difference) helps raise a younger generation to be less susceptible to the narrow nationalisms that pervade our political culture. Diverse children’s books work because – as the research of Tali Sharot shows – emotion is more persuasive than reason. They work because, by expanding our emotional life, stories show us how we are connected – offering “a glimpse across the limits of our self,” as Hisham Matar puts it. And yes, yes, I know that white supremacy, xenophobia, and fascistic nationalism are resilient and adaptable – aided, as they are, by white fragility, white innocence, and colonial amnesia. And I know that children’s literature is but one front in a larger battle. But books for young people remain one of the best resources to oppose xenophobia and the structures that sustain it because children’s literature reaches selves still very much in the process of becoming; minds that have not yet been made up; future adults who can learn respect instead of suspicion, understanding instead of fear, and yes, even love.

Emily Schneider

Philip Nel