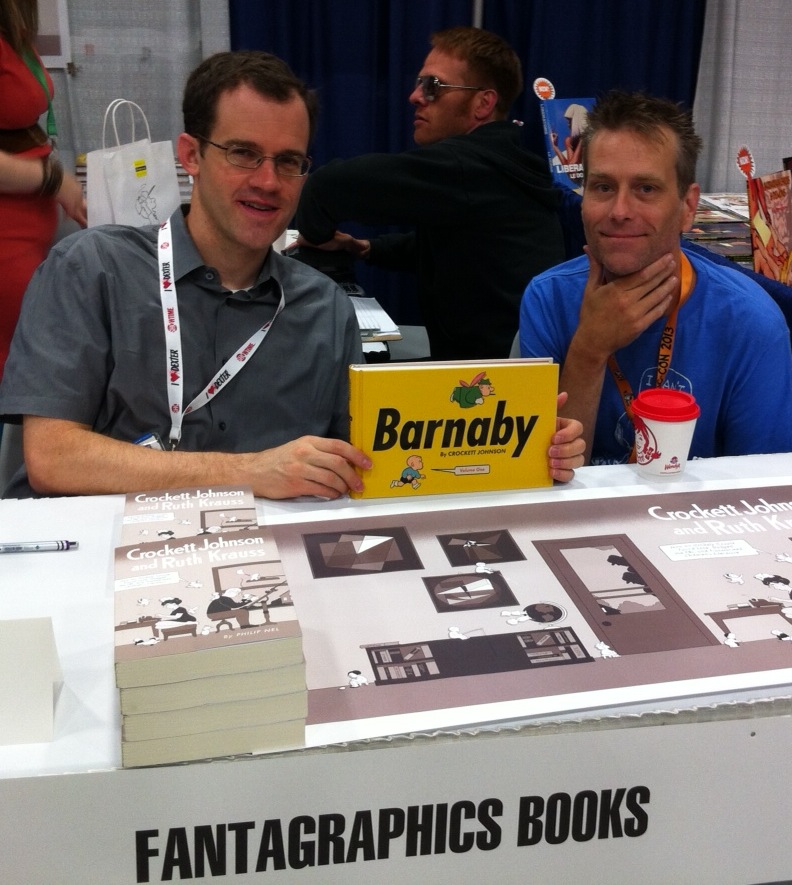

To begin today’s post, here is a photo of Eric Reynolds and I fending off the crowds at this morning’s signing.

One at a time, folks! One at a time! There are plenty of books for everyone.

Seriously. There really are plenty. I’ll be signing at the booth again on Sunday, from 2-4.

Small-Press Comics for Small People

You already know Jeff Smith’s Bone, Drawn & Quarterly’s picture-book editions of Tove Jansson’s Moomin comics (the latest is Moomin Builds a House), and Andy Runton’s Owly. But do you know these contemporary comics for young readers? I only just encountered them here, at Comic-Con.

Mike Bocianowski’s Yets! is a whimsical Walt-Kelly-esque fantasy. Though I wish the format were slightly larger (the typeface can be a bit small), but – based on my reading of the first volume – they’re charming adventures for young readers.

Mike Bocianowski’s Yets! is a whimsical Walt-Kelly-esque fantasy. Though I wish the format were slightly larger (the typeface can be a bit small), but – based on my reading of the first volume – they’re charming adventures for young readers.- Debbie Huey’s Bumperboy series features Bumperboy, his pal Bumperpup, and their friends. I haven’t read the Bumperboy Gets Angry sequence, but Bumperboy and the Loud, Loud Mountain, Bumperboy and Friends in “First Day of School”, and Pictonese Lessons are all charming.

- Konami Kanata‘s Chi’s Sweet Home stars a kitten, and may be for slightly older (say, grade-school) readers, but also very much an “all ages” comic… about a kitten!

- I already knew James Kochalka’s Johnny Boo series, about the eponymous ghost and his pet ghost Squiggle, but they’re worth a mention, too. (And they’re also on display here.)

Since I started by mentioning Owly, I must add that I bought a couple of Owly books for my niece yesterday (I didn’t buy them for myself because I already have a complete set), and Andy Runton – who is just as kind and thoughtful as you’d expect Owly’s creator to be – inscribed them to her, including some original drawings. Very cool.

Never Mind the Bullock

We tried to find the Jack Kirby Museum booth, where Charles Hatfield would be signing copies of his Jack Kirby: The Hand of Fire (2011, Eisner Award winner), and The Superhero Reader (which he co-edited, 2013). Instead, we found ourselves adjacent to a booth where Sandra Bullock was signing autographs. Later, we realized that the “5000” numbers in the convention hall are not contiguous: some are in the back left corner, and others are in the front right corner.

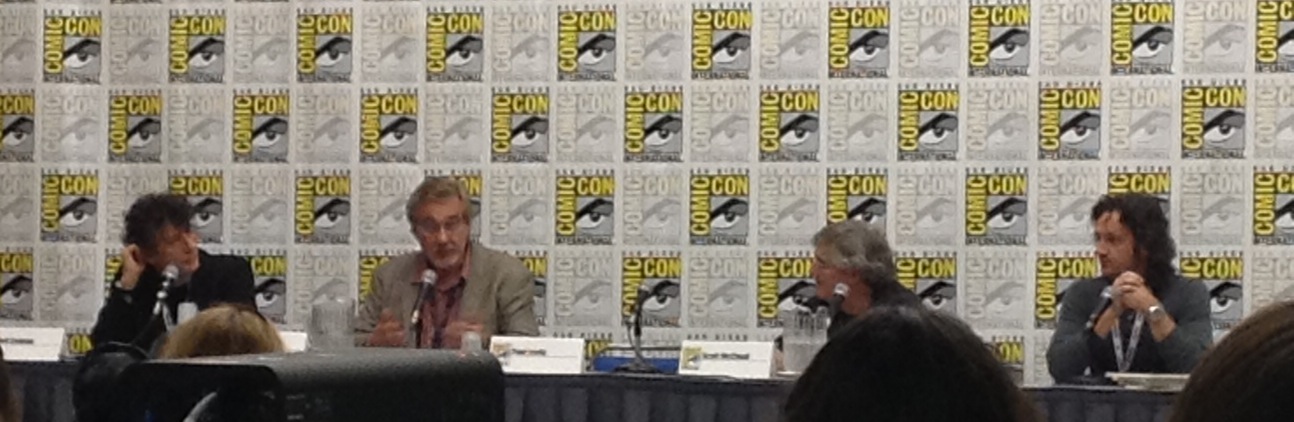

Will Eisner and the Graphic Novel

Paul Levitz, the moderator of this panel, seemed to have quite a lot to say. He really knew his subject (Will Eisner), but I kept wanting him to stop answering his questions before he had asked them.

That aside, the panelists themselves were excellent. When the panel began, Neil Gaiman had yet to arrive. But we had Denis Kitchen (literary executor for the Will Eisner Estate), Scott McCloud (Understanding Comics), and Jeff Smith (Bone).

Denis Kitchen recalled meeting Eisner during the period when Eisner was doing his educational comics. Eisner actually sought Kitchen because Kitchen was involved in underground comics, which had a different business model. The creator had copyright control, the original art would be returned to creator, and so on. This interested Eisner. So, although Kitchen had questions for Will, Will had more questions for him.

Scott McCloud said, “Will was completely different from anyone else in his generation. I saw him arguing with Will Kane about Maus. Will thought it was important for all the reasons we now know. Gil Kane thought it was so badly drawn that he couldn’t get past that.” Speaking of Eisner as an innovator, McCloud offered, “He was leading an army into battle before anyone knew there was a battle before anyone knew there was an army.” Eisner, McCloud explained, “was the first one who really understood what to do with the page.” McCloud also saw Eisner as part of the non-fiction comics revolution. “We’re only now just beginning to exploit the possibilities that he saw decades ago.” A Contract with God “is not technically the first graphic novel, but the shot across the bow that showed everyone what it could be.”

Jeff Smith told us, “I loved his drawing – the over-the-top caricature – the amount of emotion in is characters.” Smith recalls being fascinated by the fact that “there was some sense of continuity as the story developed.” He noted, for example, that when the Spirit got injured, he would be on crutches for several issues, rather then emerging in the subsequent issue fully intact. “I’d never seen that before,” Smith told us. “Will was so interested in what the new people were doing, what the young people were doing. He wasn’t just interested. He had to know…. And I believe in passing it on. I learned from him that that’s important.”

Jules Feiffer was writing Tantrum at about the same time that Will Eisner was creating A Contract with God. Why didn’t Tantrum have the impact?

Jules Feiffer was writing Tantrum at about the same time that Will Eisner was creating A Contract with God. Why didn’t Tantrum have the impact?

Jeff Smith answers, “Will was a comic book guy. Jules was a newspaper guy, known through the Village Voice and stuff like that.” And so, he said, “I don’t think it [A Contract with God] clicked at the time. I think it clicked in retrospect.” He added, “It was when you saw that next generation of comics people, … [A Contract with God] made them want to do it.”

McCloud said the problem was that “Tantrum looked at home. It looked like it belonged. Will did things that don’t belong.

At about that moment (20 minutes into the discussion) Neil Gaiman – wearing dark glasses and dressed entirely in black – arrived through a side door and walked right in front of where we were sitting. He dashed up onto the stage, and immediately entered the conversation.

Gaiman recalled, “I bought Tantrum with my own money. I was 17.” He had a very different – and, I think, better – explanation for why Tantrum didn’t click. “The pschyo-sexual odyssey of a 40-year-old man was less accessible than A Contract with God.” And “It didn’t look like a comic.”

Gaiman remembered meeting Will Eisner, and he spoke of “Having learned everything I knew about comics from Will, going out and buying Comics and Sequential Art,” which became his guide for how to write comics. Then, once he wrote comics, he wanted “to do something that was good enough for him. He remembered giving Signal to Noise to Eisner, in an elevator, and then listened to Eisner while he told Gaiman his thoughts on Signal to Noise. All of the panelists conveyed the sense that Eisner was not just generous to the younger generation but genuinely interested in their work. One reason, Gaiman said, was that Eisner “wanted it [comics] to expand. He wanted it to embiggen.”

Gaiman remembered meeting Will Eisner, and he spoke of “Having learned everything I knew about comics from Will, going out and buying Comics and Sequential Art,” which became his guide for how to write comics. Then, once he wrote comics, he wanted “to do something that was good enough for him. He remembered giving Signal to Noise to Eisner, in an elevator, and then listened to Eisner while he told Gaiman his thoughts on Signal to Noise. All of the panelists conveyed the sense that Eisner was not just generous to the younger generation but genuinely interested in their work. One reason, Gaiman said, was that Eisner “wanted it [comics] to expand. He wanted it to embiggen.”

Here is an amusing exchange about Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, which Neil Gaiman read when it was still in draft form.

Scott McCloud: I was a stone-cold formalist. Neil had to harangue me into a chapter about storytelling.

Neil Gaiman: I don’t know that I harangued you. I remonstrated.

Levitz says, “Let’s get back to influence.” Gaiman tells the following story:

I interviewed Will. The last one we did was on stage. And we talked for an hour. … The bit of the conversation I remember was asking will why he kept doing it…. Why are you bringing graphic novels out now at an age when all your contemporaries are retired are dead or both. And he started talking about a film which he saw in which Kirk Douglas played a trumpet player, and he was looking for the note. And if he kept playing his trumpet , he would find the note, and he could finish. And he described his entire career as being in search of the note. He knew he could hear this thing somewhere up ahead, and he wouldn’t need to do anything after that. And he’d finish it, and he’d look at it, and the note would still be moving across the horizon, and so he’d still keep looking.

Jeff Smith offers, “Will provided a good example of how to do a career. I’d look at him and say I want to do that job. That’s a good job. …. Will was still really active…. He was still present, he was still around. That’s the model. Why not go for it? Why stop? This was my sense from him.”

McCloud says, “I’d go one step further and say that he was certainly a role model for me. He was pretty much the whole package. I saw the relationship he had with Ann. I wanted to have that kind of relationship with my wife, Ivy.” McCloud notes, too, that Eisner “was always open to change” and that he was “optimistic — in the good sense of the word, not the deluded sense.”

Kitchen adds, “He was intellectually curious. He was not like most old people I knew. Of his generation, no one else was even willing to read underground comics. He not only looked at them. They influenced him. It was people like Justin Green and Jack Jackson that he found very influential. He was happy to talk about it, and he was happy to credit them.”

Neil Gaiman asks, “Do ever you think it would be interesting if he had really done the autobiographical comic that he could have done?”

Kitchen: The Dreamer is the closest he comes.

Kitchen: The Dreamer is the closest he comes.

Gaiman: The Dreamer is a kind of greatest hits. He kind of flirted with autobiography. He took his experience, and he Eisnerized it.

Kitchen: The Dreamer is the one where he pulled his punches.

Kitchen also tells us that he had to push Eisner on The Dreamer, trying to get him to say more. Eisner, explained that he couldn’t do autobiographical comics because “I’m not like Crumb. I can’t let it all hang out.”

Jeff Smith recalled that, when Scholastic wanted to publish Bone, Smith said OK, if you’re going to do that, you have to put it with the other books. You can’t put it with the Dungeons and Dragons. He added “That was me channeling Will.”

Neil Gaiman observed, “He set up the publishing model that gave him The Spirit. I encountered Will [Eisner’s work] for the first time in a proto-comics shop when I was 15. … On the wall in this basement was The Spirit, no. 2, Harvey edition. I had no idea they were done in the 1940s. They were the best storytelling I’d ever seen. … Will, unlike pretty much everyone else of his generation, had not sold his baby.”

Levitz introduces the topic of what was learned from Eisner.

Gaiman answers, “Share knowledge. Be collegiate. That was one of the most interesting things I learned.” Smith and McCloud concur.

There was no time for audience questions.

Team Cul de Sac

Deftly moderated by Tom Racine, this all-star panel included Chris Sparks, Lincoln Pierce, Mark Tatulli, Lucas Turnbloom, Jenni Holm, Matthew Holm, Andrew Farago, Shaenon Garrity, Rob Harrell.

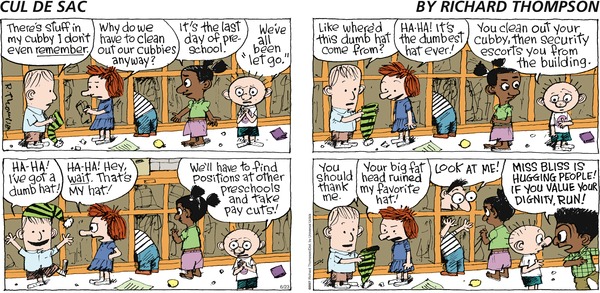

First, if you haven’t read Richard Thompson’s Cul de Sac, what are you waiting for? Though Thompson’s Parkinsons has (temporarily?) cut short its run, the strips have been collected in several volumes, and The Complete Cul de Sac is due out this fall. In the early days of this blog, I did a brief post on it. But you should go and read the strip itself.

First, if you haven’t read Richard Thompson’s Cul de Sac, what are you waiting for? Though Thompson’s Parkinsons has (temporarily?) cut short its run, the strips have been collected in several volumes, and The Complete Cul de Sac is due out this fall. In the early days of this blog, I did a brief post on it. But you should go and read the strip itself.

If you’re not a Cul de Sac fan, you may not know about Chris Sparks’ Team Cul-de-Sac: Cartoonists Draw the Line at Parkinsons, a book which has raised over $105,000 for Parkinsons research. Sparks, who invited cartoonists to contribute to a book honoring Cul de Sac and Thompson, won the Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award at the Eisners last night.

Sparks tells of how he met Richard Thompson, and how devastated he was when he learned that his favorite comic-strip artist had contracted Parkinsons. He read Michael J. Fox’s book Always Looking Up: The Adventures of an Incurable Optimist, and decided that “If a rich good-looking movie star could do this, then so could a poor web designer.”

Here’s what some of the other panelists had to say about Thompson and Cul de Sac:

“The best comic strip since Calvin and Hobbes, one of the best comic strips of all-time.”

— Lincoln Pierce

“He’s one of my heroes”

— Lincoln Pierce

“Petey is one of the most perfect comic strip characters of all time. I used to think you couldn’t do better than Charlie Brown, as the everyman. And yet Petey is more idiosyncratic….”

— Lincoln Pierce

“What I love about Richard’s work is that it doesn’t appear to have any sort of forethought….. It’s very natural and very loose”

— Mark Tatulli

“Petey is my favorite character…. I can remember that from my childhood”

— Mark Tatulli

“I thought there was a lot of mediocrity in the comics, and it’s just not fair”

— Mark Tatulli, on why he created his specific contribution to Team Cul de Sac

In case you don’t know the strip, here is a Cul de Sac for you to enjoy.

More quotations from panelists:

“It’s just the perfect comic. It’s one of those things where you look at your work and you think I’m doing it wrong. This is right. And I’m doing it wrong.”

— Lucas Turnbloom

“Our entire adulthood was shaped by Parkinsons.”

— Jenni Holm on her and her brother Matt; their father had Parkinsons

“His writing is so amazing because he just nails family life. The funny dynamics between the mom and the kids, and the kids and the kids. It’s so hard to pull off.”

— Jenni Holm on Richard Thompson’s writing

“It feels like an autobiographical strip I did as a weird 10-year-old kid, sitting in my room and reading comics while all the other kids are playing baseball.”

— Andrew Farago

“The combination of art and writing in the strip is perfect. … They capture the character and the sense of humor at the same time.”

— Shaenon Garrity

“I worship his art.”

— Rob Harrell

“I don’t want to speak for everybody else, but I feel like we’re all faking it and he’s the real deal.”

— Mark Tatulli

“One of the great things about all comics is that as you read them you see that they have their own obsessions. And one of Richard’s is shopping carts”

— Lincoln Pierce

From Comic Book Artist to Fine Artist Extraordinaire: A Chat with Robert Williams

This panel featured Karl Meyer, Eric Reynolds, Robert Williams (of course!), Gwenned Vitello, and William Stout.

I went to this panel because Eric was on it and because I knew nearly nothing about the artist, who (I learned) started as an underground cartoonist – was one of the original Zap Comix artists – and in the 1970s began to create fine art. The art itself reminds me of Dalí and R. Crumb. Robert Williams is a contemporary of Crumb (and they were/are friends) – so, I’m not suggesting his work is derivative of Crumb, but rather that they’re artistic kin. Stylistically, Williams does not use Crumb’s squiggly line but Dalí’s crisp, precise, realistic renderings of (often) impossible scenes. Fun fact for ’80s metal fans: Robert Williams did the original cover art for Guns ‘n’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction.

A few quotations from the panel.

“The ideas do not come easy. They have to be excreted under pressure.”

— Robert Williams

“He’s taken some of the tropes of comics and infused them into his fine art.”

— Eric Reynolds

“Put enough color and action in there so that it [the image] sticks with ’em [the audience], whether they like it or not.”

— Robert Williams

“There would be no Fantagraphics if it weren’t for Zap Comix”

— Eric Reynolds

Another interesting tidbit I learned: Leonardo diCaprio’s father, George diCaprio, was an underground comix distributor.

Williams had lots of great stories, which I would record here … if I wasn’t so fatigued at the end of the day (this panel began at 7).

My Dinner with Eric

What? You think I’m going to write up my dinner with Eric Reynolds? Sorry. This blog post has gotten long enough. We did have a great chat, though — always great to hang out with Eric. He’s a good person, and I feel very fortunate to be working with him on the Barnaby books. Oh, did I mention — another signing on Sunday, 2-4 pm, Fantagraphics? I did? Good, then I’ll see you there, at booth 1718.

The rest of my 2013 Comic-Con coverage:

JoeyC

Philip Nel

Eli

Philip Nel

Pingback: Comic-Con’s comics winners and losers