This election. You’re tired of it. I’m tired of it. And… it’s finally over. Today. Or, at least we hope it will be resolved today. Given that Mr. Trump has vowed only to accept a Trump victory, it may not be resolved today. Either way, the 2016 U.S. Election is one for the history books – and for children’s books. We have yet to read the children’s book about this presidential contest, but four picture books on the candidates offer a first draft of history for younger readers.

A few months ago, I was talking to a German reporter about picture books on presidential candidates – he was genuinely surprised that there were already children’s books about Clinton and Trump. After all, neither had yet attained the office! But it didn’t surprise me. During the 2008 presidential election, there were twelve juvenile titles about then Senator Barack Obama – two of them picture books. During that same election, there were five books for young readers about Senator John McCain – one of those, a picture book (My Dad, John McCain, by his daughter Meghan).

This year, we already have three picture books about Hillary Clinton – one of which, Kathleen Krull and Amy June Bates’ Hillary Rodham Clinton: Dreams Taking Flight (2015) has been updated since its initial appearance in 2008. The other two are new for this election: Michelle Markel and LeUyen Pham’s Hillary Rodham Clinton: Some Girls are Born to Lead (2016) and Jonah Winter and Raul Colón’s Hillary (2016). On the Republican side, there’s just one: Michael Ian Black and Marc Rosenthal’s A Child’s First Book of Trump (2016), which might also be called an adult satire masquerading as a children’s book.

This year, we already have three picture books about Hillary Clinton – one of which, Kathleen Krull and Amy June Bates’ Hillary Rodham Clinton: Dreams Taking Flight (2015) has been updated since its initial appearance in 2008. The other two are new for this election: Michelle Markel and LeUyen Pham’s Hillary Rodham Clinton: Some Girls are Born to Lead (2016) and Jonah Winter and Raul Colón’s Hillary (2016). On the Republican side, there’s just one: Michael Ian Black and Marc Rosenthal’s A Child’s First Book of Trump (2016), which might also be called an adult satire masquerading as a children’s book.

Or it might not. Representing the American Trump (as Black calls him) requires a journey into areas where most children’s books fear to tread. Lucky for Black and Rosenthal, they created the book before the emergence of the tape in which Trump bragged about committing sexual assault, before he was openly flirting with using nuclear weapons (and encouraging their proliferation), before he challenged the patriotism of a Gold Star family, before he went on a late-night Twitter rant against a former Miss Universe, before he (twice) suggested that his supporters assassinate Hillary Clinton, and before he said he would only accept the election results if he won. Writing a Trump picture book now – even a picture book for adults – would be much more challenging.

Or it might not. Representing the American Trump (as Black calls him) requires a journey into areas where most children’s books fear to tread. Lucky for Black and Rosenthal, they created the book before the emergence of the tape in which Trump bragged about committing sexual assault, before he was openly flirting with using nuclear weapons (and encouraging their proliferation), before he challenged the patriotism of a Gold Star family, before he went on a late-night Twitter rant against a former Miss Universe, before he (twice) suggested that his supporters assassinate Hillary Clinton, and before he said he would only accept the election results if he won. Writing a Trump picture book now – even a picture book for adults – would be much more challenging.

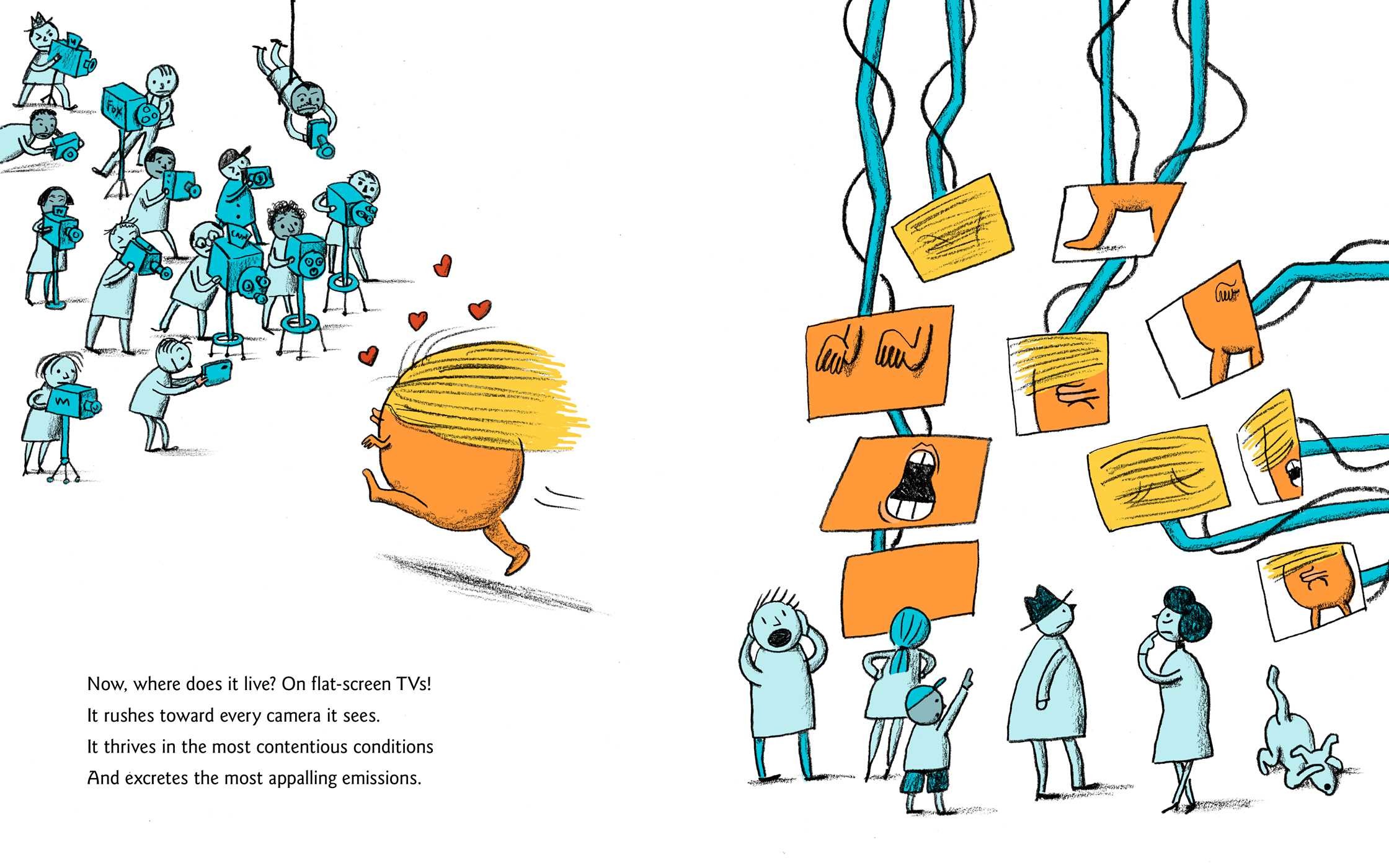

Even though it misses some of Mr. Trump’s more recent offenses, A Child’s First Book of Trump does not shy away from his tiny hands, his anxiety about “the size of [his] manhood,” his need to attach his name to products of dubious merit, his fixation on always “winning,” or his obsession with TV coverage. “Now, where does it live?” Black asks of the Trump. “On flat-screen TVs! / It rushes toward every camera it sees. / It thrives in the most contentious conditions / And excretes the most appalling emissions.”

The ersatz Seussian verse is no accident. Black represents Trump as a con-artist straight out of Seuss. In A Child’s First Book of Trump, Trump’s personality is part unreformed Grinch and part Sylvester McMonkey McBean, the salesman who profits from the Sneetches’ prejudice (in Seuss’s The Sneetches). Visually, Rosenthal depicts the Trump as an oversized yam with a comb-over. He’s a compelling character for a children’s book: an ego that is both inflated and fragile; a volatile, impulsive personality; a pathological need for attention. He is the shining example of how not to behave. He is not even a “he.” He is an “it,” a non-gendered, primal, howling ball of need.

Where Black and Rosenthal can draw upon the ready-made caricature of the man himself, the creators of the Hillary Clinton books face the challenge of both presenting a complex, multi-dimensional adult, and finding a clear narrative through-line. For the latter, all three underscore Clinton’s life and work as a feminist achievement, illustrating her Wellesley commencement speech, as well as her work as a lawyer, First Lady, U.S. senator, 2008 presidential candidate, and U.S. Secretary of State.

Where Black and Rosenthal can draw upon the ready-made caricature of the man himself, the creators of the Hillary Clinton books face the challenge of both presenting a complex, multi-dimensional adult, and finding a clear narrative through-line. For the latter, all three underscore Clinton’s life and work as a feminist achievement, illustrating her Wellesley commencement speech, as well as her work as a lawyer, First Lady, U.S. senator, 2008 presidential candidate, and U.S. Secretary of State.

The feminist narrative is compelling: it gives her struggle a sharp focus, and invites readers to root for her as she surmounts (or does not surmount) tough odds. When the story of the 2016 campaign gets added to revised editions of these books or told in new books, a feminist emphasis will contrast decisively with her opponent’s prolific misogyny. Indeed, in these children’s books of the future, Mr. Trump’s sexist thuggery will make him a convenient foil for Secretary Clinton.

The feminist narrative is compelling: it gives her struggle a sharp focus, and invites readers to root for her as she surmounts (or does not surmount) tough odds. When the story of the 2016 campaign gets added to revised editions of these books or told in new books, a feminist emphasis will contrast decisively with her opponent’s prolific misogyny. Indeed, in these children’s books of the future, Mr. Trump’s sexist thuggery will make him a convenient foil for Secretary Clinton.

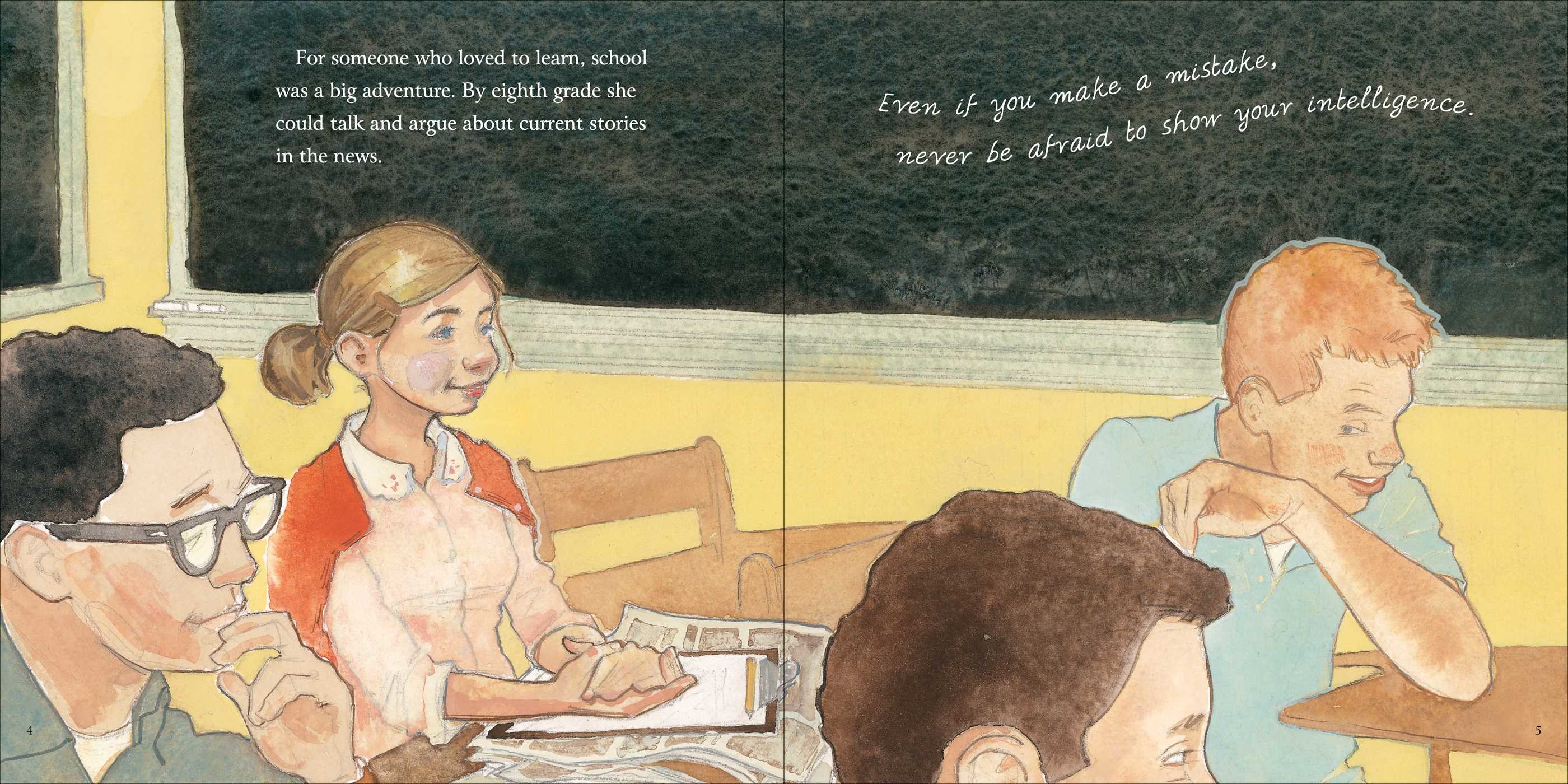

In the current editions, the feminist emphasis sometimes risks oversimplifying. While I understand Krull’s desire to wrest a moral from each moment of Clinton’s life, the homily on every two-page spread feels condescending, as if the book doesn’t trust readers to make sense of the narrative. After a teen-age Hillary writes to NASA to volunteer to be an astronaut, the agency turns her down: “But it was 1961, and some paths were still closed to women, such as the job of astronaut.” On the same page and in a cursive script, the book adds “Take a deep breath, look ahead, and keep trying to fly.” If these inspirational moments admirably address a lack of heroes for girls, they also insist upon the book’s authority, denying readers the pleasure of drawing their own lessons from its story.

Aided by the expressive faces and body language in Pham’s artwork, Markel’s Hillary Rodham Clinton: Some Girls Are Born to Lead offers the sharpest focus on her subject’s battle against institutional sexism. Nearly every two-page spread confronts the double standard that Hillary has faced throughout her life. While campaigning with Bill, the narrative observes, “She wasn’t frightened of the cameras and reporters. But she couldn’t believe how people criticized her – in ways they’d never criticize a man.” By delivering this critique via free indirect discourse (third person closely aligned with first-person perspective, Hillary in this case), Markel softens the didacticism, while still highlighting the considerable gender bias – which, as Samantha Bee and others have pointed out, has been a dominant theme of the 2016 campaign.

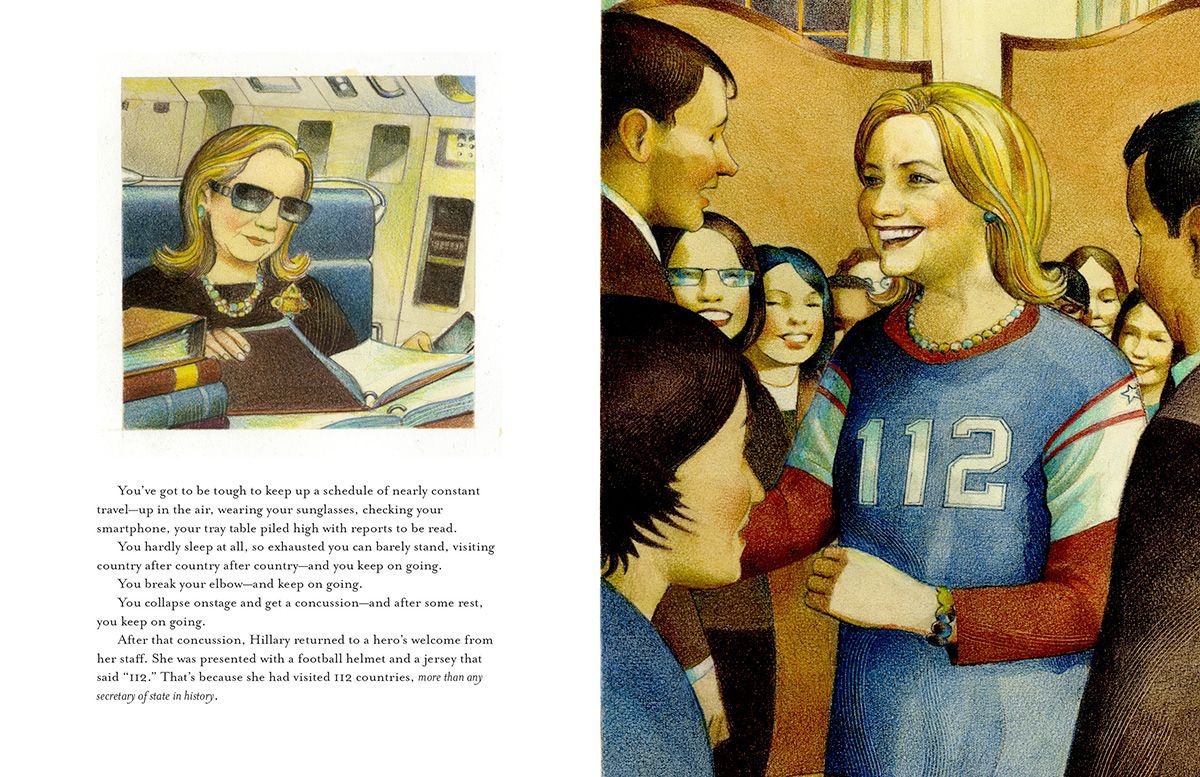

Winter and Colón’s Hillary manages the feminist message subtly, via compelling anecdotes that speak for themselves. Visiting Egypt as Secretary of State, Clinton stands poised behind a podium, heedless of the men who point and shout at her. Winter’s narrative reports: “In Egypt, where women do not have as many rights as men, she gave a speech that called for equality between men and women. She was challenged by men in the audience: how dare she come to Egypt and tell them what to do? Hillary did not back down.” The sharpness of Winter’s text and warmth of Colon’s artwork (a mix of watercolors, colored pencils and lithograph crayons), taken together, conveys just the right mix of toughness and compassion.

The books about Hillary steer clear of Bill’s infidelities. On the one hand, this seems fair: his philandering is not her fault, and so need not be part of her story. On the other, it seems a lost opportunity: her ability to stick with a wayward spouse would offer some insight into their relationship. The sole book about Donald also omits his three marriages, many affairs, and avocational groping. Here, the omission is a flaw: Trump’s view that women are objects tells us much about his character, and should be included. It could serve as a cautionary tale for young readers, telling boys how not to behave, and all children about the type of boy they should avoid.

When picture-book creators of the future (or these authors, in revised editions) tell the story of this election, they’ll face the challenge of including language and behavior typically excluded from works for young readers, where pussy-grabbing typically refers to picking up a cat and not to sexual assault. It’s quite possible that children’s books about the 2016 election will land on the American Library Association’s Banned Book List.

However, if that proves to be the case, then so be it. Lying to children does not help them understand the world in which they live. The truth is that, in 2016, the Republican Party nominated a thin-skinned, unhinged, narcissistic, sociopathic, misogynist, racist, conspiracy-theorist-spouting con artist. Most members of his party were the contemporary equivalent of good Nazis: they professed disagreement with some of his statements, but otherwise endorsed their candidate. Should Mr. Trump win, children’s books about this election will be shelved next to children’s books about the rise of Mussolini, Hitler, Franco, Stalin, and other authoritarian rulers. The books will be cautionary tales about how fascism can ransack democracies.

If Secretary Clinton wins, the U.S. will have at least won an electoral victory over an aspiring tyrant, even though he, his followers, and the party that nominated him will not have disappeared. Discovering how to lead Trumpites and Trump-supporting Republicans back to democracy will be one of the major challenges of a Hillary Clinton administration.

As I write these words in the earliest hours of November 8th, we do not yet know the election’s outcome – though polling suggests that Secretary Clinton will prevail, thanks in large part to high voter turnout among Hispanics, African Americans, and other minoritized groups. Indeed, in the grandest of ironies, all those whom the U.S. has historically treated badly – if they vote in sufficient numbers – will save America from itself.

And that’s a story worth telling.

Other posts about the 2016 U.S. Election:

- Trump Is the Voldemort of Presidential Candidates (30 Sept. 2016)

- Election 2016: The Mixtapes (28 Sept. 2016)

- How Do We Stop the Trump on the Stump? The Truth Is in Seuss! (28 March 2016)

- The Treachery of Images (20 March 2016)