Welcome to another installment in my ongoing list of the Best Books for Young Readers. Admittedly, any such list will reflect the list-maker’s (in this case, my) idiosyncracies. But, since people often ask me about great books for small humans, I’ve been creating the “ideal” library for my nearly three-year-old niece, Emily, and writing about it in this “Emily’s Library” series. I hope it may be of use to other children and the book-buying adults in their lives. Since she’s growing up speaking English, French, and a little Swiss German (Basel Deutsch, to be precise!), you’ll see some – though not enough – French books, and the occasional German book. English-speakers, don’t panic: all (or nearly all) can be found in English translation as well.

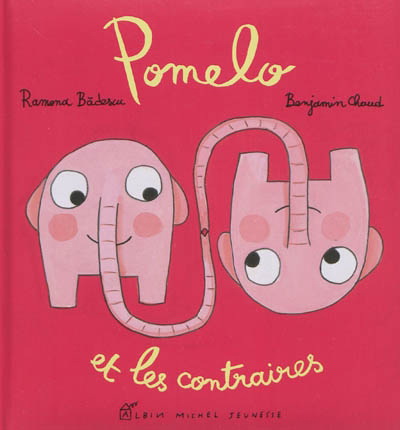

Ramona Badescu and Benjamin Chaud, Pomelo et les contraires (2011) [Pomelo’s Opposites (2013) in its original French]

A small book starring our favorite little grapefruit-colored elephant, Badescu and Chaud’s Pomelo et les contraires explores not just pairs of opposites but the very concept of opposites. Not just high and low, but handsome and weird. Not only black and white, but gastropod and cucurbit. Not merely hard and soft but everything and nothing. Because Pomelo (or a transformation of Pomelo) illustrates most pairs of opposites, you get the sense of a world measured in units of little pink elephants. (For more Pomelo, see Part 6 of the Emily’s Library series.)

A wordless book about perspective. With each turn of the page, we have zoomed out, further away from the view on the previous page. What the Eames’ Powers of Ten does for mathematics, Banyai‘s Zoom does for perspective. Even after you’ve read it once and so know what’s coming next, it’s nonetheless satisfying to see how each page makes the next page possible, and then the following page, and so on.

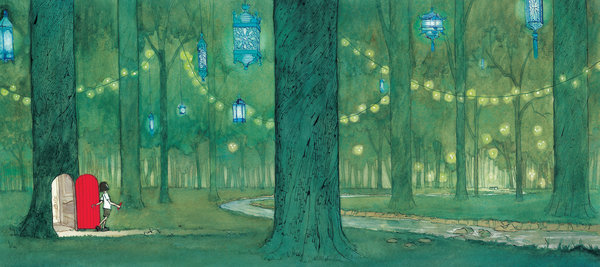

Aaron Becker, Journey (2013)

An homage to Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon and one of the best books of 2013, Aaron Becker‘s Journey follows a young girl’s imagination into a world of Miyazaki-esque wonder. It’s a beautiful wordless picture book that rewards re-readings.

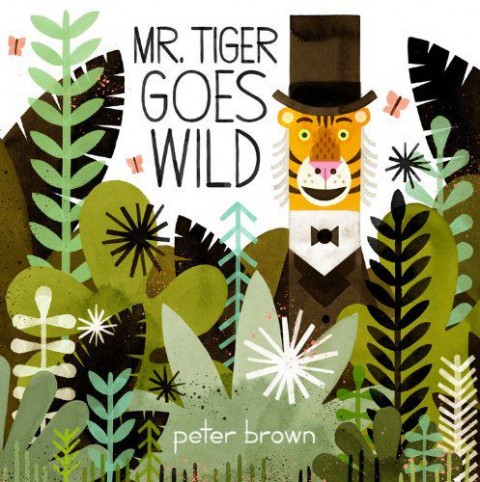

Peter Brown, Mr. Tiger Goes Wild (2013)

Since Emily is already a fan of Squeaker (from Peter Brown’s Children Make Terrible Pets), the latest Peter Brown book was a natural choice. Echoing Sendak by way of Charley Harper and Mary Blair, Mr. Tiger finds that he has a bit of a … wild streak. And so, off he goes, streaking into the wild. It’s a book about sloughing off the expectations of civilization, a tale of releasing one’s inner wildness, and resisting conformity. It’s also funny.

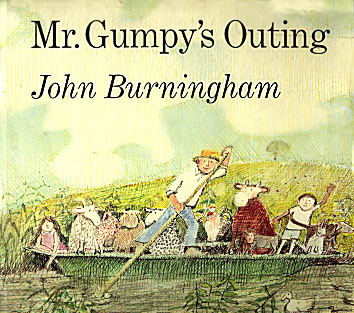

John Burningham, Mr. Gumpy’s Outing (1970)

Classic tale of a boat ride that, with each addition of a new animal, sets up the inevitable capsizing. Children can join the boat ride, as long as they “don’t squabble.” A rabbit can get on board as long as it doesn’t “hop about.” A cat may come, but it’s “not to chase the rabbit.” And so on. A gentle, whimsical tale, told with economy and humor.

Those who are not academically inclined should skip this paragraph. The rest of you should read Perry Nodelman’s “Decoding the images: how picturebooks work,” from Peter Hunt’s Understanding Children’s Literature, Second Ed., pp. 128-139. It’s a magnificent close-reading of the book, and a great example of showing how rich and complex the apparently simple picture book really is.

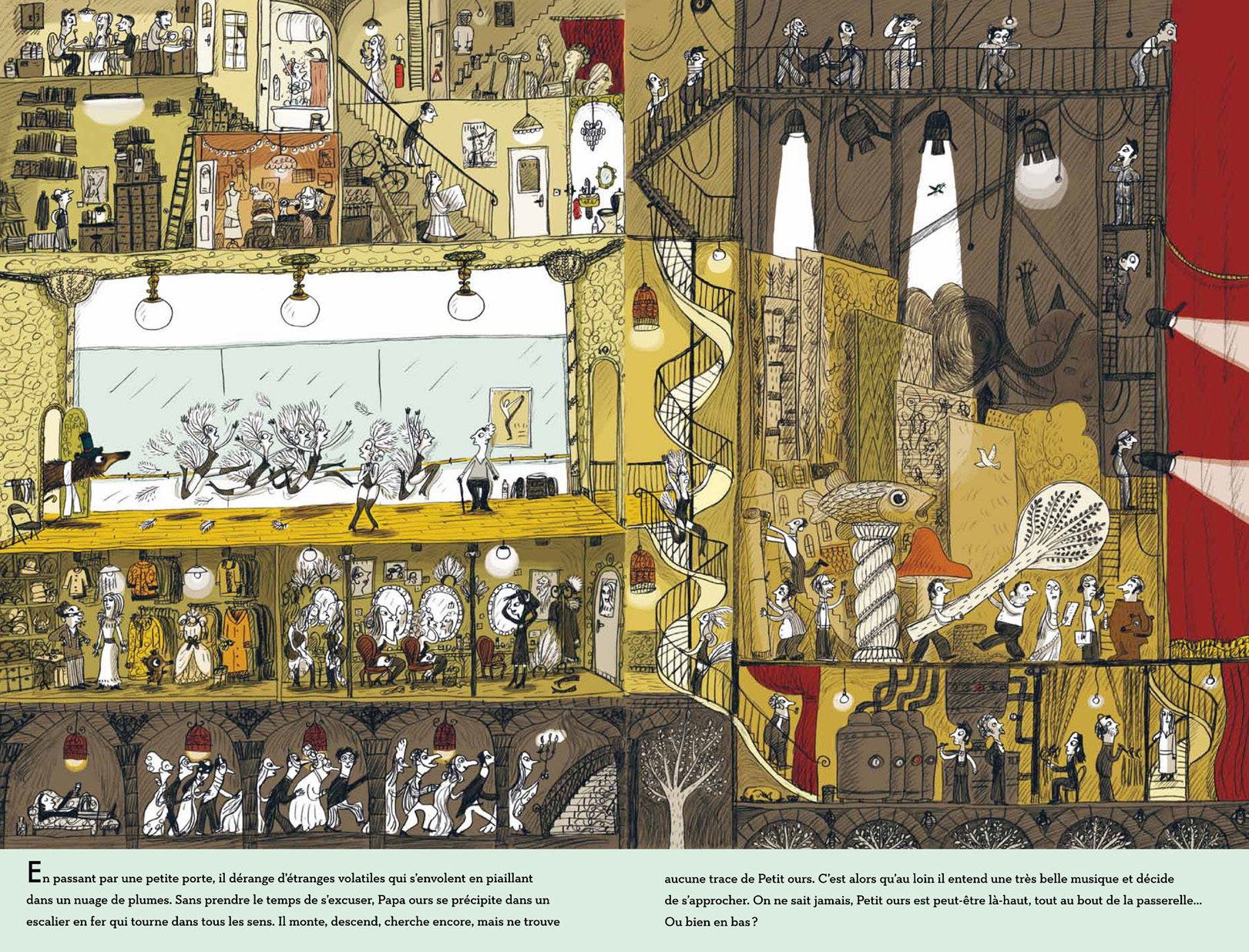

Benjamin Chaud, Une chanson d’ours (2011) [The Bear’s Song (2013) in its original French]

Papa Bear is getting ready to hibernate, but where has Little Bear gone? On each giant two-page spread, Chaud’s Little Bear is running along chasing a bee, but there’s so much more to see: other animals, hunters, cars, bicyclists, dancers, and much more. So, each two-page spread offers not only the game of finding Little Bear, but also of identifying as many other items (and the subplots they imply). I think that telling you about the chanson [song] would spoil the surprise. So, I’ll let you find that for yourself.

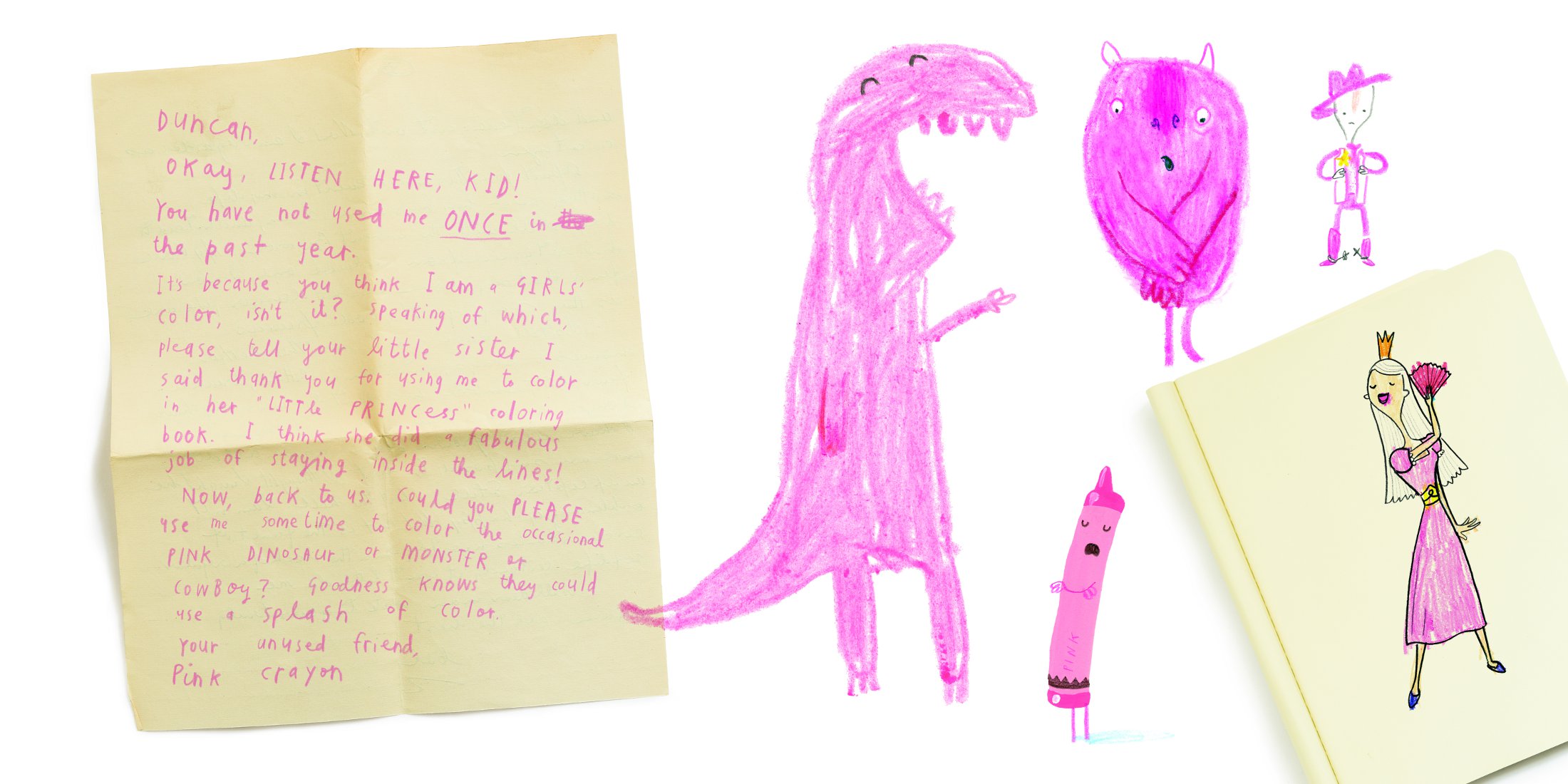

Drew Daywalt and Oliver Jeffers, The Day the Crayons Quit (2013)

A gift to Emily from my stepsister Janet, Daywalt and Jeffers‘ book imagines crayons in revolt. White feels ignored, blue over-used, black irritated by only being used for outlines. And what happened to peach’s wrapper? He feels naked without it. These are among the box of problems that Duncan faces. How can he make all the crayons feel involved?

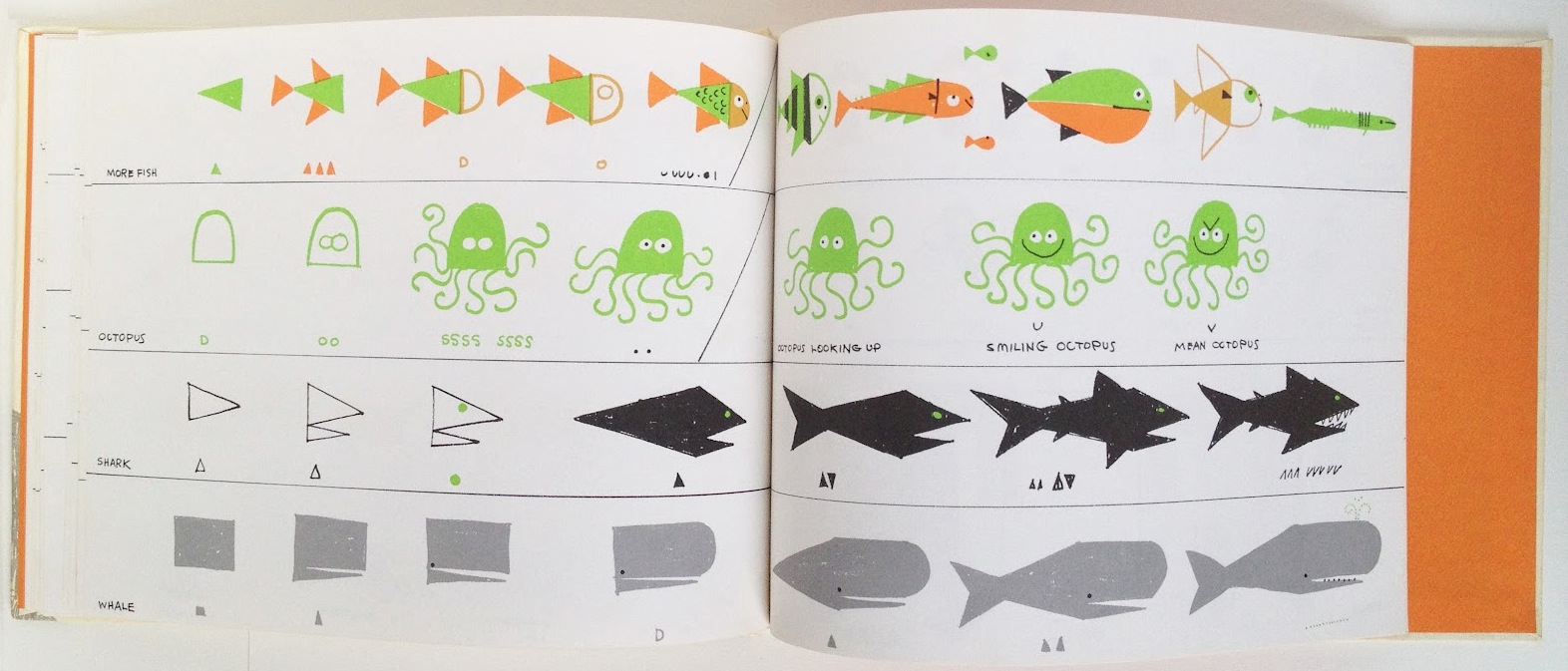

Ed Emberley, Ed Emberley’s Drawing Book of Animals (1970)

This one is a favorite from my childhood. Emberley shows how, with just a few simple shapes, you can draw all sorts of animals: dogs, cats, birds, a dragon. The instructions unfold rather like those for assembling Lego: one picture at a time, and each new one clearly indicates what you’ll be adding. At present, the book is an occasion for the (not yet 3-year-old) Emily to ask others to draw the pictures for her. But, eventually, I think she’ll be drawing the animals herself. She loves to draw, though – in this phase of her artistic development – most of her art tends to be non-representational.

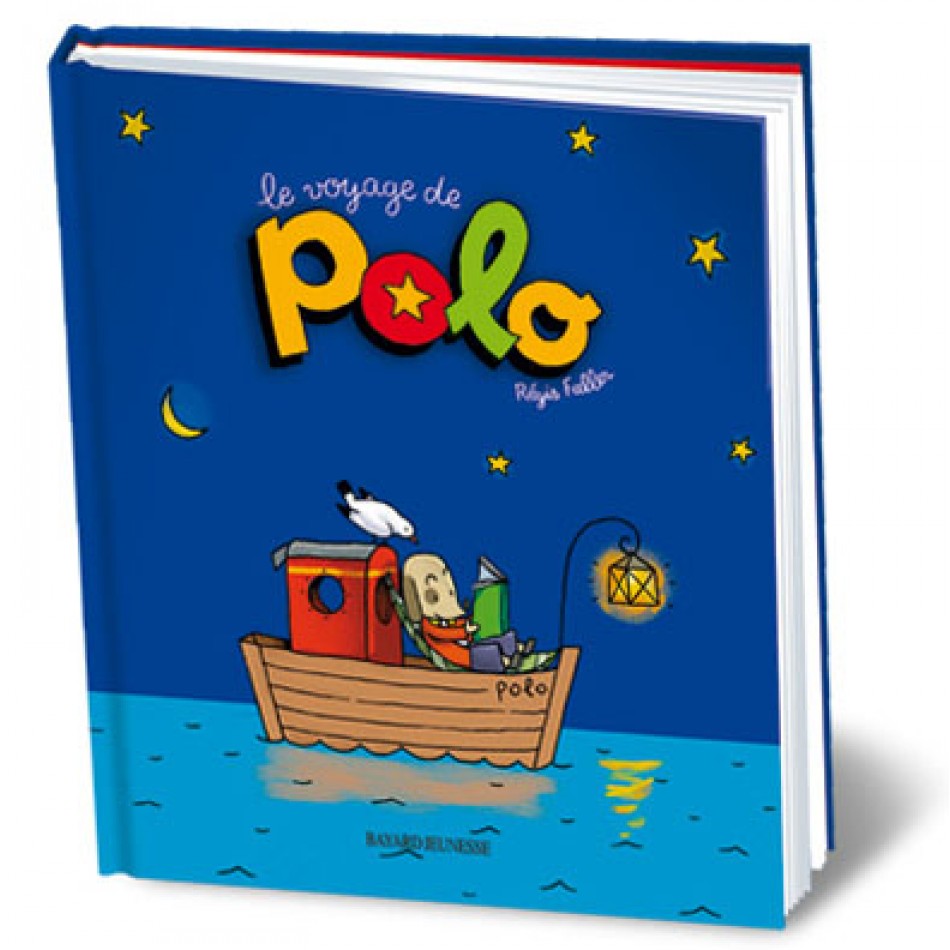

Régis Faller, Le Voyage de Polo (2002) [The Adventures of Polo (2006) in French]

The first in Faller’s books about a small anthropomorphic dog who (generally) lives on his own, and then embarks upon an adventure. The Polo stories have an associative narrative logic evocative of the Harold stories’ structure. In this one, he opens the door of his island tree home, walks over to a tightrope, and then starts carefully to make his way along it – shades of Harold’s tightrope act in Harold’s Circus (1959). The tightrope suddenly becomes stairs, which Polo then climbs – reminiscent of the stairs in Harold’s Fairy Tale (1957). Beyond those direct visual allusions (or, at least, they feel like allusions), the story’s art manages to link each panel to the next, and then to the next. You don’t quite know where Polo is going, but he’s traveling with a purpose, and fun to accompany for the duration of his journey. Like the Harold stories, Le Voyage de Polo recalls the mode of storytelling favored by creative young people: there is a logic, but it makes sense only to the storyteller. However, Faller and Johnson tell the tale in a way that it all makes sense to readers, too.

The first in Faller’s books about a small anthropomorphic dog who (generally) lives on his own, and then embarks upon an adventure. The Polo stories have an associative narrative logic evocative of the Harold stories’ structure. In this one, he opens the door of his island tree home, walks over to a tightrope, and then starts carefully to make his way along it – shades of Harold’s tightrope act in Harold’s Circus (1959). The tightrope suddenly becomes stairs, which Polo then climbs – reminiscent of the stairs in Harold’s Fairy Tale (1957). Beyond those direct visual allusions (or, at least, they feel like allusions), the story’s art manages to link each panel to the next, and then to the next. You don’t quite know where Polo is going, but he’s traveling with a purpose, and fun to accompany for the duration of his journey. Like the Harold stories, Le Voyage de Polo recalls the mode of storytelling favored by creative young people: there is a logic, but it makes sense only to the storyteller. However, Faller and Johnson tell the tale in a way that it all makes sense to readers, too.

All wordless (save for the occasional sound effect), the Polo books are among Emily’s favorites. A tip of the virtual hat to Julie Walker Danielson for introducing me to them.

Régis Faller, Polo et le Dragon (2003) [Polo and the Dragon (2009)]

At the onset of winter, Polo dons his coat and hat, and sets off in his boat – only to find himself snowbound and icebound. Fortunately, because he is Polo, he’s able to draw a doorway in the ice (another echo of Harold and the Purple Crayon), open the door, and walk through it. I could summarize the rest of this story, but why would you want me to? Just go and read it.

Régis Faller, Polo et la flute magique (2003) [Polo and the Magic Flute (2009)]

Régis Faller, Polo et la flute magique (2003) [Polo and the Magic Flute (2009)]

In which Polo travels by sea, on foot, atop a snail, and learns that music can make you fly. Which, of course, it can.

Régis Faller, Polo and Lily (2009) [Polo et Lili (2004) in English because the French edition was unavailable]

Lovely story about Polo and his friendship with the free-spirited Lily [Lili in French]. The two quickly become close friends but – spoiler alert! – Lily stays true to her independent nature, and continues traveling. For me, this book is about having a close friend whom you rarely see in person.

Régis Faller, Polo and the Magician! (2009) [Polo magicien! (2004) in English because the French edition was unavailable]

A rainstorm! A flood! And Polo drifts into a starring role in the circus. Though it shares the earlier book’s associative logic, Polo and the Magician! features different adventures than Crockett Johnson’s Harold’s Circus (1959). Indeed, one contrast between the two is that while Harold’s adventures are always solitary, Polo frequently makes friends, such as the magician in this book, or Lily in the last (she also makes a cameo appearance in this one). But all other characters Harold encounters are the creation of his crayon.

A rainstorm! A flood! And Polo drifts into a starring role in the circus. Though it shares the earlier book’s associative logic, Polo and the Magician! features different adventures than Crockett Johnson’s Harold’s Circus (1959). Indeed, one contrast between the two is that while Harold’s adventures are always solitary, Polo frequently makes friends, such as the magician in this book, or Lily in the last (she also makes a cameo appearance in this one). But all other characters Harold encounters are the creation of his crayon.

Régis Faller, Polo: À la recherché de Lili (2010)

As yet unavailable in English, this nearly wordless tale finds Polo seeking Lili [Lily, in English], and is in this sense a sequel to Polo et Lili. A larger-sized Polo book, it’s also a sequel to many of the other books in the series, referencing the Dragon, the Magician, and some new characters, too.

Don Freeman, Corduroy (1968)

This one is a gift from what we’ll call Emily’s grandmother-in-law once removed (I have no idea if there’s a word for what my mother-in-law is to Emily). If you live in North America, I’ll hazard a guess that you know this one already. But, in case not, Corduroy is a teddy bear whose overalls are missing a button, and so Lisa’s mother elects not to buy him for Lisa. This prompts Corduroy, after hours, to wander all over the department store, seeking a button. And that’s a big part of the fun here: getting to explore, unsupervised, a vast place full of stuff. Corduroy fails in his quest, but Lisa returns the next day, buys him with her own pocket money, and stitches a button on his overalls.

This one is a gift from what we’ll call Emily’s grandmother-in-law once removed (I have no idea if there’s a word for what my mother-in-law is to Emily). If you live in North America, I’ll hazard a guess that you know this one already. But, in case not, Corduroy is a teddy bear whose overalls are missing a button, and so Lisa’s mother elects not to buy him for Lisa. This prompts Corduroy, after hours, to wander all over the department store, seeking a button. And that’s a big part of the fun here: getting to explore, unsupervised, a vast place full of stuff. Corduroy fails in his quest, but Lisa returns the next day, buys him with her own pocket money, and stitches a button on his overalls.

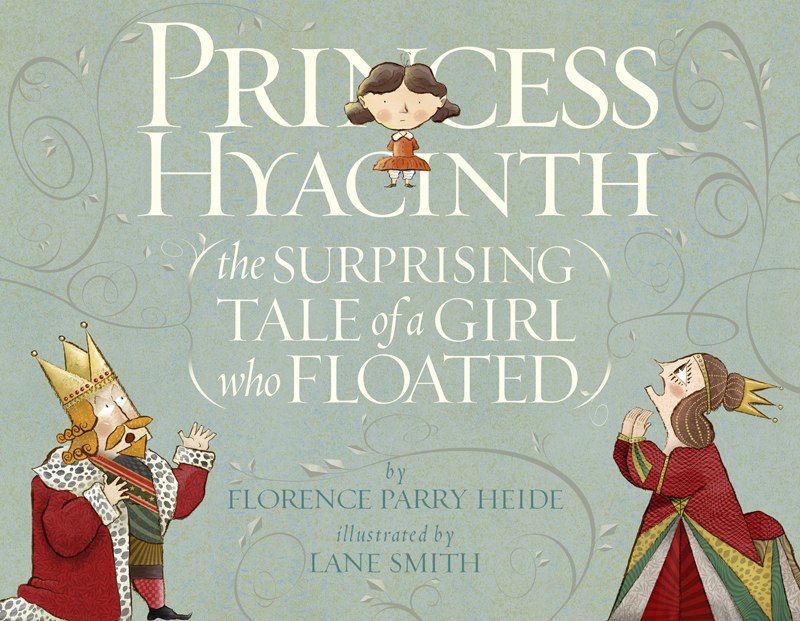

Florence Parry Heide and Lane Smith, Princess Hyacinth (The Surprising Tale of a Girl Who Floated) (2009)

Brought to life by Lane Smith’s art and Molly Leach’s dynamic book design, Heide’s final story (she died in 2011) tells of a young girl who is happiest when she’s floating. Her parents worry about her floating off, and so find ways to tether her to the ground. But she resists being tethered. A fine tale that, in the spirit of other books by both Smith and by Heide, celebrates the non-conformist.

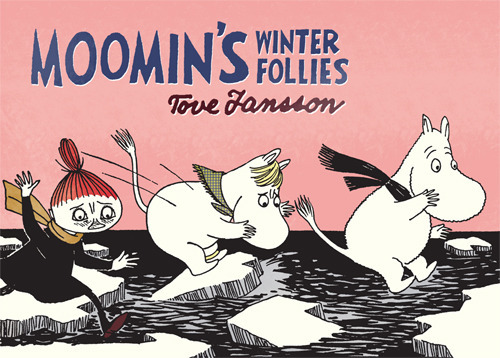

Tove Jansson, Moomin’s Winter Follies (1955/2012)

Drawn & Quarterly have been releasing Tove Jansson’s Moomin comics (1954-1959) both in large format, featuring the original black-and-white daily strips, and in smaller format, featuring colored versions of the daily strips. This book and the two listed below are the smaller-format ones.

Drawn & Quarterly have been releasing Tove Jansson’s Moomin comics (1954-1959) both in large format, featuring the original black-and-white daily strips, and in smaller format, featuring colored versions of the daily strips. This book and the two listed below are the smaller-format ones.

Since the comic strip told a series of (mostly) self-contained stories, dividing them up into these smaller books both makes narrative sense and offers a great introduction to the world of the Moomins and their friends. The comics are a bit looser than the novels, and include characters and situations that never appear in either the picture books or the chapter books. This one introduces the irritatingly enthusiastic Mr. Brisk, who loves winter weather and sports. (As you might expect, the Moomins don’t entirely share his love for competitive athletics.)

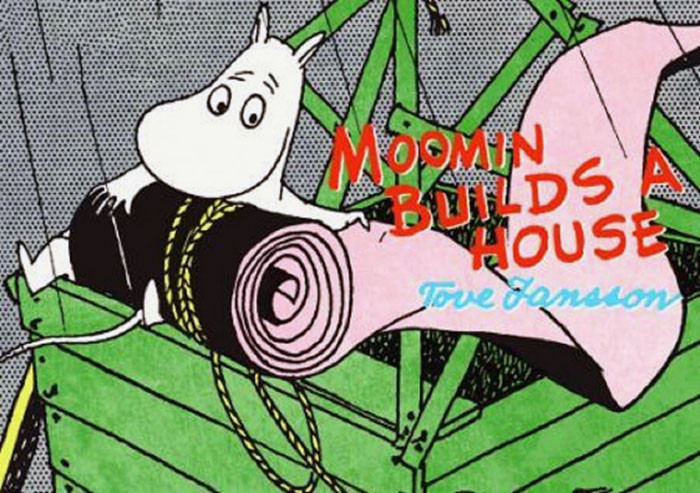

Tove Jansson, Moomin Builds a House (1956/2013)

Introducing the character of Little My (whose first line is “I’m Little My! And I bite because I like it!”), this story finds the Moomins coping with trying houseguests, too many small children (Little My’s siblings), and an irritatingly careless parent (the Mymble, mother to Little My). Tired of always having to yield his room to others, Moomintroll decides to build his own house … which proves trickier than he thought it would.

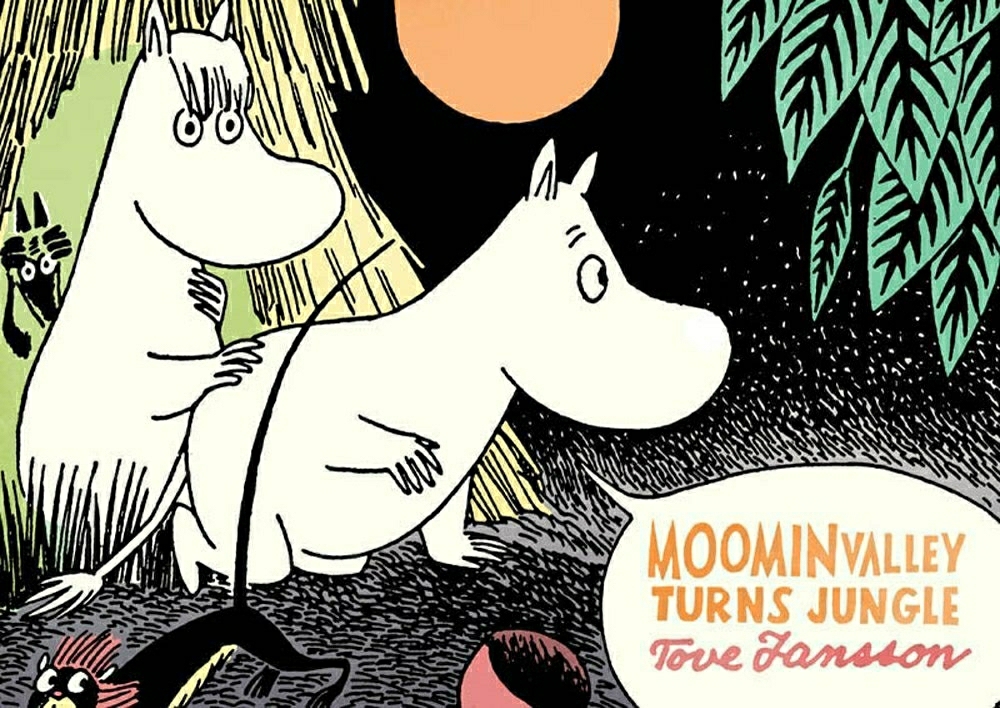

Tove Jansson, Moominvalley Turns Jungle (1956/2012)

After a drought, Moominvalley gets thunderstorms, watering the tropical seeds that Little My has found. Then, Stinky liberates animals from the zoo… and the Moomins have an adventure in their own backyard (and in their own home). Transforming the home – via flood, winter, absence, or (in this case) plant life – is a recurring theme in the Moomin books. It’s both an exciting transformation of the everyday, and makes the characters even fonder of the home they’ve lost… and which they get back, by story’s end.

After a drought, Moominvalley gets thunderstorms, watering the tropical seeds that Little My has found. Then, Stinky liberates animals from the zoo… and the Moomins have an adventure in their own backyard (and in their own home). Transforming the home – via flood, winter, absence, or (in this case) plant life – is a recurring theme in the Moomin books. It’s both an exciting transformation of the everyday, and makes the characters even fonder of the home they’ve lost… and which they get back, by story’s end.

Crockett Johnson, La Plage Magique (2006) [French translation of Magic Beach (2005/1965)]

Crockett Johnson, La Plage Magique (2006) [French translation of Magic Beach (2005/1965)]

An unusual book, and one of Crockett Johnson’s most developed examinations of the thin boundary between real and imagined worlds. The book is probably better suited for children slightly older than Emily (I’d say 5 or 6), but when I discovered a French translation of something to which I’d written the Afterword, I couldn’t resist sending it to her.

Ole Könnecke, Das große Buch der Bilder und Wörter (2011) and Le grand imagier des petits (2010) [The Big Book of Words and Pictures (2012) in German and French]

With the enthusiasm and scope of Richard Scarry, Könnecke fills his pages with labeled anthropomorphic animals and their daily lives. Also like Scarry, Könnecke’s two-page spreads tell lots of small stories. There’s a child (represented by a little bear) getting dressed. There’s an energetic toddler (represented by an elephant) playing a pot like a drum, running around, and merrily heedless of the parent trying to sleep. There’s the cycle of life, told via a bird and his vehicles (baby buggy, scooter, bicycle, car, walker, wheelchair). There’s even an allusion to Harold’s purple crayon. Unlike Scarry, the art is a bit more ligne claire, and the pages are both fewer and thicker – not quite “board book” but headed in that direction. So, a great title for the three-and-under set.

With the enthusiasm and scope of Richard Scarry, Könnecke fills his pages with labeled anthropomorphic animals and their daily lives. Also like Scarry, Könnecke’s two-page spreads tell lots of small stories. There’s a child (represented by a little bear) getting dressed. There’s an energetic toddler (represented by an elephant) playing a pot like a drum, running around, and merrily heedless of the parent trying to sleep. There’s the cycle of life, told via a bird and his vehicles (baby buggy, scooter, bicycle, car, walker, wheelchair). There’s even an allusion to Harold’s purple crayon. Unlike Scarry, the art is a bit more ligne claire, and the pages are both fewer and thicker – not quite “board book” but headed in that direction. So, a great title for the three-and-under set.

I bought Emily the original German edition, and the French translation. I should probably send her a copy of the English-language translation also. Then, as she begins to read, she can put all three books side by side and compare the different languages.

Barbara Lehman, Rainstorm (2007)

Another wordless tour de force from Barbara Lehman, Rainstorm unfolds in comics panels and bright colors. During a rainstorm, a lonely boy in a big house finds a key. The key opens a trunk, revealing a ladder that descends to… where? I’d rather not summarize. If you’ve enjoyed Lehman’s other works (The Red Book, Museum Trip, Trainstop), you’ll enjoy this one – and, I expect, whatever book she publishes next. Lehman’s one of my favorite contemporary artists of books for children.

Andy Runton, Owly: Just a Little Blue (2005)

The second of Runton’s wordless narratives finds the titular protagonist – and his companion, Wormy – wanting to help some smaller birds. Though he has the best of intentions in building the birdhouse, the smaller birds don’t trust him. This makes sense to me: owls are raptors; they prey on smaller animals. Owly, of course, does no such thing. But the birds who don’t know him are wary.

Andy Runton, Owly: Flying Lessons (2006)

Another peculiarity of Owly is that, though he is ostensibly an owl, he does not fly. He walks everywhere. The flying in this book gets done by the flying squirrel. Another tale of friendship and attempts to make new friends. And, as always, it all happens without words – or, rather, with only the occasional sound effect or (when speech is required) pictograph. One reason I’ve been giving Emily wordless books is that I like wordless books, but another is that they’re international – you can read them in any language.

Another peculiarity of Owly is that, though he is ostensibly an owl, he does not fly. He walks everywhere. The flying in this book gets done by the flying squirrel. Another tale of friendship and attempts to make new friends. And, as always, it all happens without words – or, rather, with only the occasional sound effect or (when speech is required) pictograph. One reason I’ve been giving Emily wordless books is that I like wordless books, but another is that they’re international – you can read them in any language.

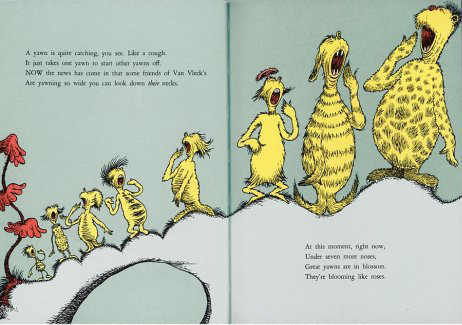

Dr. Seuss, Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book (1962)

Will a book full of so many fantastic creatures excite the imagination into wakefulness or lull the mind into slumber? I’m not sure and (as with all books) results may vary. But I’ve fond memories of this book from my own childhood, from the brushing of teeth at Herk-Heimer Falls, to the notion of a yawn (and sleep) spreading, to the Chippendale Mupp who bites his tail at bedtime as an alarm clock: “His tail is so long, he won’t feel any pain / ’Til the nip makes the trip and gets up to his brain. / In exactly eight hours, the Chippendale Mupp / Will, at last, feel the bite and yell ‘Ouch’ and wake up.” As each day and my endurance wanes, I still think of – and feel a bit like – the Collapsible Frink, about to collapse in a heap.

Dr. Seuss, Fox in Socks (1965)

I’ve long thought that Dr. Seuss intended this book as a prank on parents and other adults. Beginning readers, who read more slowly than adults, actually have a much better chance of pronouncing these tongue-twisters correctly. In contrast, the confident grown-up, sure of his or her ability, begins reading this book aloud, but immediately stumbles. And then stumbles again, and again. This, of course, is one reason the book is so much fun: children get to see adults struggling with words.

Dr. Seuss, Hop on Pop (1963)

Given (some) small children’s proclivity for seeing the adults in their lives as sophisticated playthings, I expect many a “Pop” has been hopped upon, thanks to this book. Yes, the Pop in the book says, “STOP / You must not / hop on Pop.” But the children do hop on Pop, and the book’s title can be read as advice, supplemented by a demonstration (the cover shows the brother and sister hopping on Pop). That said, the book does of course contain a variety of silliness. As one of Seuss’s concept books, Hop on Pop collects mostly unrelated couplets, some of which sustain narrative over a few pages, but most of which do not. One of the multi-page tales tells of sitting connoisseur Pat. He sits “on hat,” on “cat,” and balances rather precariously on the handle end of a baseball bat. Happily, a character arrives to keep Pat’s sitting mania under control. Just as he’s about to sit on a cactus, this character intervenes: “NO PAT NO / Don’t sit on that.” Mischievous, and fun to read aloud.

Given (some) small children’s proclivity for seeing the adults in their lives as sophisticated playthings, I expect many a “Pop” has been hopped upon, thanks to this book. Yes, the Pop in the book says, “STOP / You must not / hop on Pop.” But the children do hop on Pop, and the book’s title can be read as advice, supplemented by a demonstration (the cover shows the brother and sister hopping on Pop). That said, the book does of course contain a variety of silliness. As one of Seuss’s concept books, Hop on Pop collects mostly unrelated couplets, some of which sustain narrative over a few pages, but most of which do not. One of the multi-page tales tells of sitting connoisseur Pat. He sits “on hat,” on “cat,” and balances rather precariously on the handle end of a baseball bat. Happily, a character arrives to keep Pat’s sitting mania under control. Just as he’s about to sit on a cactus, this character intervenes: “NO PAT NO / Don’t sit on that.” Mischievous, and fun to read aloud.

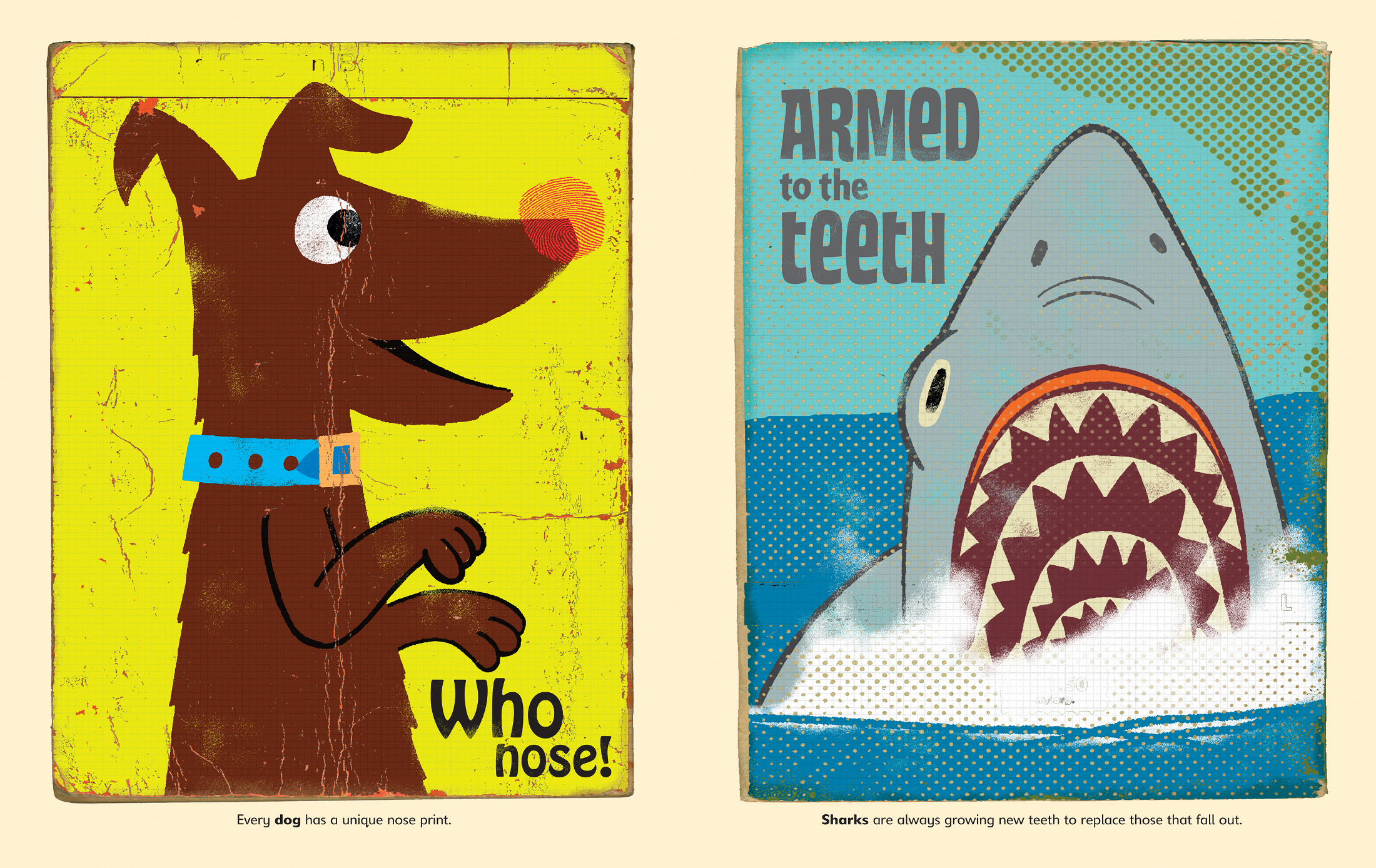

Paul Thurlby, Paul Thurlby’s Wildlife (2013)

Since she was an early adopter of Paul Thurlby’s Alphabet (“A is for Awesome!”) and she loves visiting animals in the zoo, Emily seemed the ideal candidate for Paul Thurlby’s Wildlife. Like its predecessor, the book’s bold, humorous art recalls mid-twentieth century posters. In this one, however, each animal is accompanied by an unusual fact. Beneath the poster of a disco-dancing bee, Thurlby’s text tells us that “Bees talk to one another by dancing in patterns.”

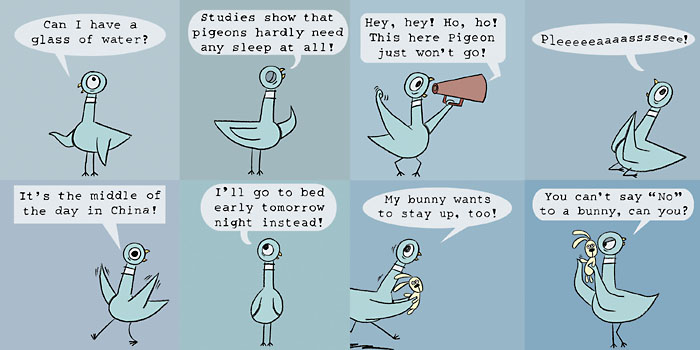

Mo Willems, Don’t Let the Pigeon Stay Up Late (2006)

Yes, yes, you know the formula – the direct address from the pigeon, monochromatic backgrounds that convey mood, and the expressive minimalism of the pigeon himself. And Willems knows the formula, too. Happily, with each new pigeon book, he manages to keep it fresh and funny.

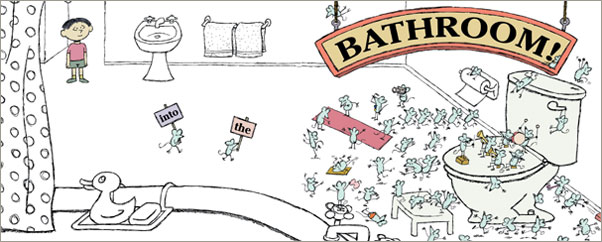

Mo Willems, Time to Pee (2003)

Sign-wielding mice help children learn what to do when they “get that funny feeling.” With gentle humor and a keen consideration of children’s feelings, Willems helps young people learn what to do when it’s time to pee! As Emily is currently potty training, this book is of particular interest to her.

Jennifer Yerkes, Drole d’oiseau (2011) [A Funny Little Bird (2013) in its original French]

With ingenious use of negative space, Yerkes creates a character who is nearly invisible – on a white page, he only appears when contrasted with other, colored items. Though he at first feels sad, a risky experiment in gathering colorful accouterments teaches him that the ability to avoid detection is in fact a powerful gift. Lovely graphic design aids the book’s gentle moral.

Note: I’ve borrowed the term “small humans” (used in the title of and elsewhere in this blog post) from my friend and colleague Erica Hateley.

| When possible, I’ve bought each of these books locally, ordering via Claflin Books & Copies.

Amazon.com is a sweatshop, and (when I can) I prefer to buy from places that are not. |

|---|

Looking for other great children’s books? Try these blogs:

- Elizabeth Bird’s Fuse #8

- Julie Walker Danielson’s Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast

- Travis Jonker’s 100 Scope Notes

- Anita Silvey’s Children’s Book-a-Day Almanac

- Follow The Niblings on Twitter or Facebook

Related posts on Nine Kinds of Pie:

- Emily’s Library, Part 1: 62 Great Books for the Very Young (2 Jan. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 2: Wordless Picture Books (3 Jan. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 3: En Français (4 Jan. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 4: Ten Alphabet Books (24 Feb. 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 5: 29 More Books for the Very Young (22 May 2012)

- Emily’s Library, Part 6: 35 More Books for the Very Young (21 April 2013)

- How to Find Good Children’s Books (April 2011)

- Desert Island Picture Books (Oct. 2011)

- Mock Caldecott, 2013: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2013)

- Mock Caldecott, 2012: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2012)

- Mock Caldecott, 2011: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2011)

- Mock Caldecott, 2010: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2010)

That’s the end of this installment, but there will be more “Emily’s Library” features in the future.

JoeyC

Philip Nel