Welcome to a new feature on Nine Kinds of Pie: “Emily’s Library.” It’s named for my eight-month-old niece, and it will highlight only the very best children’s books. When I learned that my sister was expecting, I decided to create for her child an ideal library of children’s books. She and her spouse could read them to her, and, eventually, Emily could read the books herself.

Welcome to a new feature on Nine Kinds of Pie: “Emily’s Library.” It’s named for my eight-month-old niece, and it will highlight only the very best children’s books. When I learned that my sister was expecting, I decided to create for her child an ideal library of children’s books. She and her spouse could read them to her, and, eventually, Emily could read the books herself.

Since I began this project, I’ve found myself sharing my list of “Emily” books with other parents or parents-to-be. With “Emily’s Library,” I will now be sharing it with you.

What do I mean by “ideal” or “the very best”? I’m still developing my criteria, but here’s what I have so far.

- Old and new. Classics, but also more recent books. I want neither to reify the past, nor to dwell solely in the present. Rather, I’d like a range of works from then and now.

- Difference. This is fairly broadly defined. I’m thinking of different types of stories (different genres), different nationalities, different ethnicities, different artistic styles….

- I want some emphasis on children’s books originally in French. Emily and her parents live in Switzerland. My sister and brother-in-law speak English, French, German, and Spanish, but they’ll be raising Emily primarily in English and French. Since I don’t speak French, I’ve been reading French books in translation, and then sending Emily the original French-language editions. A broader implication of this criterion is a need to read children’s books that originate in countries (and languages) other than one’s own.

- The theme of wordless picture books is (in part) a response to the language issue. Art is legible in any language. Readers can create their own words, changing those words with each reading if they wish. Or they can experience the story fully through the language of pictures. Wordless picture books also feature on this list because they’re great examples of narrative art: they prove, definitively, that a story does not require words. Art is so central to the picture book that, as part of his final revision process, Shaun Tan “test[s] for wordless comprehension. I remove the text and see if it works by itself. And if it does I feel that that’s a successful story.” And, finally, wordless picture books are here because I happen to like them.

- Which brings me to the question of taste. Since it reflects my likes and dislikes, the list will be somewhat idiosyncratic. So, for example, you’ll notice that I’m drawn to humor.

- Politically acceptable, inasmuch as possible. The list will not be strictly “politically correct” because: I’m inherently suspicious of orthodoxies, some classics that don’t reflect contemporary social values remain worth reading, and books can be interpreted in many ways. By this last point I mean to say that (with a few exceptions) a book is not a tract: whatever political messages it may harbor, there’s no guarantee that a reader will discern them… simply because literature doesn’t work that way. Having said that, I am interested in books that may teach Emily to respect those who are different from herself, to be receptive to ideas that challenge the status quo, to think critically, and to imagine… whatever she wants.

- All of these books are for Emily, and thus reflect my own imagination – what I think she or her parents may enjoy, what might make her smile, give her pleasure, or grant her some insight. Since she is only eight months old, I am of course projecting onto her my own sense of who she is or might become.

I’ve listed these points to underscore the subjectivity of this endeavor. I have written books and articles on children’s literature, I teach courses on children’s literature, and I have amassed a certain amount of “expertise” in the field. However, I’m acutely aware of how much I have yet to learn, I recognize that tastes vary, and I know that my aesthetic criteria are (as yet) rather vague. If this list does represent a literary canon of sorts, it also acknowledges that canon-formation is an idiosyncratic, flawed, and tricky business.

In sum, I think all of these books are good. You may disagree, or have favorites of your own that I’ve failed to list. Please feel share your disagreements and suggestions in the comments section below. As I say, I know that I’ve much to learn, and would be delighted to learn about other great children’s books.

Without further prologue, here are some of the first 62 books I’ve sent to Emily. I’ll post more tomorrow and Wednesday, continuing with semi-regularly posts throughout Emily’s childhood.

Janet and Allan Ahlberg, Each Peach Pear Plum (1978)

Enjoy the rhymes, have fun finding nursery-rhyme characters. Great for very young readers.

Sandra Boynton, Hippos Go Berserk! (1977, rev. 2000)

A counting book featuring the humor and hippos of the inimitable Sandra Boynton.

Sandra Boynton, Snoozers: 7 Short Short Bedtime Stories for Lively Little Kids (1997)

“I’m not tired!” The reliably funny Sandra Boynton offers tales for bedtime. Also features words and music to “Silly Lullaby” (later recorded for Philadelphia Chickens). I’ve bought Emily quite a few Boynton books – in part ’cause Emily’s mother likes them, and in part ’cause I do. Here are the other titles I’ve sent:

- But Not the Hippopotamus (1982)

- Pajama Time (2000)

- 15 Animals (2008)

Jeff Brown, Flat Stanley, illus. Tomi Ungerer (1964)

A favorite of mine when I was in first grade. Then, this book appealed to me because it suggested that the imagination could alter the physical universe – Stanley’s near two-dimensionality seemed so real to me. As an adult, I love the book’s dry humor, sense of the absurd, and its silliness. There’s also one joke that Emily may appreciate far sooner than children who only speak English. The “head of the Famous Museum of Art” is Mr. O. Jay Dart. Get it? His name puns on objet d’art (French for “work of art”).

Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd, Goodnight Moon (1947)

Brown’s verse and Hurd’s post-impressionist art combine to deliver the pleasures of evading bedtime. (For more about the book, see Leonard Marcus’s biography of Brown or his The Making of Goodnight Moon.)

Peter Brown, Children Make Terrible Pets (2010)

The central conceit – swapping human and animal roles – is both comic and instructive. If animals saw us as we see them, what would they see?

Virginia Lee Burton, Katy and the Big Snow (1943)

Virginia Lee Burton, Katy and the Big Snow (1943)

Along with Keats’ The Snowy Day and Takao’s A Winter Concert, this was one of a trio of winter-themed books sent to Emily in late October 2011. It’s another favorite from my own childhood. As I did then, I love the images of Katy plowing everyone out, the paths she cuts across the landscape, discovering roads where there had been only snow. There’s something powerful in the book’s presentation of a relatively small being (Katy) remaking a vast snowy landscape. It suggests that strength need not derive from size.

Eric Carle, The Very Hungry Caterpillar (1969, rev. 1987)

You know this one, don’t you? I’d be surprised if you didn’t. It’s a great example of Carle’s vibrant collage-style illustration and storytelling. Check it out.

Chih-Yuan Chen, Guji Guji (2003, English translation 2004).

When the title character (a crocodile raised by ducks) meets crocodiles who want to eat his family, he realizes that – though he may not be a duck – he needs to defend those he loves. Told with a gentle sense of humor, the book addresses difference without being preachy.

Donald Crews, Freight Train (1978)

Bold colors, clean layout, a “simple” idea beautifully realized. Those last five words identify a key part of my aesthetic criteria.

Tim Egan, Friday Night at Hodges Café (1994)

I’ve previously devoted a whole blog post to Tim Egan’s work. He deserves much, much more attention than he has thus far received. And this book contains one of my favorite lines in all of children’s literature: “Too bad his duck was so crazy.”

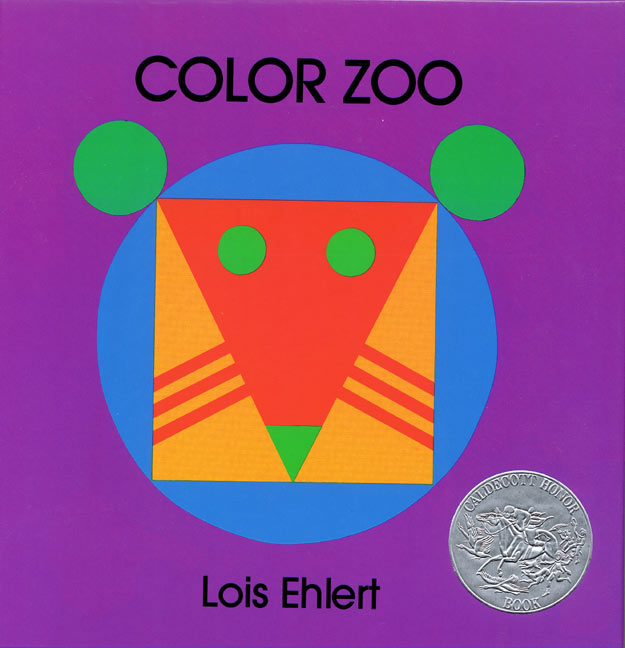

Lois Ehlert, Color Zoo (1989)

Lois Ehlert, Color Zoo (1989)

Turn the die-cut pages to see shapes become animals. See also Ehlert’s companion book, Color Farm (1990). Bright colors, clever design. A Caldecott Honor book. In its board book incarnation, great for the youngest readers.

Ian Falconer, Olivia (2000)

The book that launched the literary career of that precocious pig, Olivia is an Eloise for contemporary children. In addition to his sense of humor, Falconer is also great at using white space to pace his narrative. I imagine him making detailed sketches, and then reducing those to just the vital visual information.

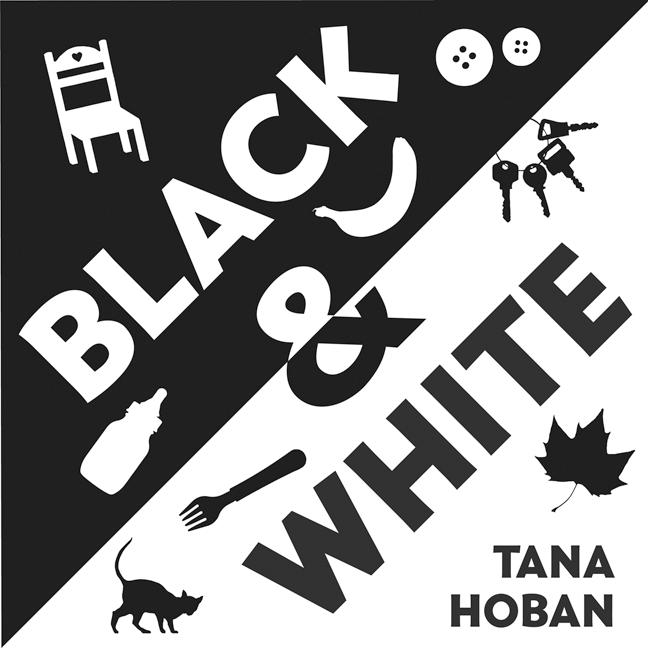

Tana Hoban, Black and White (2007)

Tana Hoban, Black and White (2007)

This book – and its companions Black on White (1993) and White on Black (1993) – show black shapes on white backgrounds and vice-versa. Buttons, a sailboat, a fork, a flower, a banana. The pages unfold accordion-style so that you can stand the book up around a baby, and she can look at the images. The sharp contrast between black and white make the shapes especially vivid to infants (whose eyes are still developing the capacity to focus). This is one of the first books that really interested Emily.

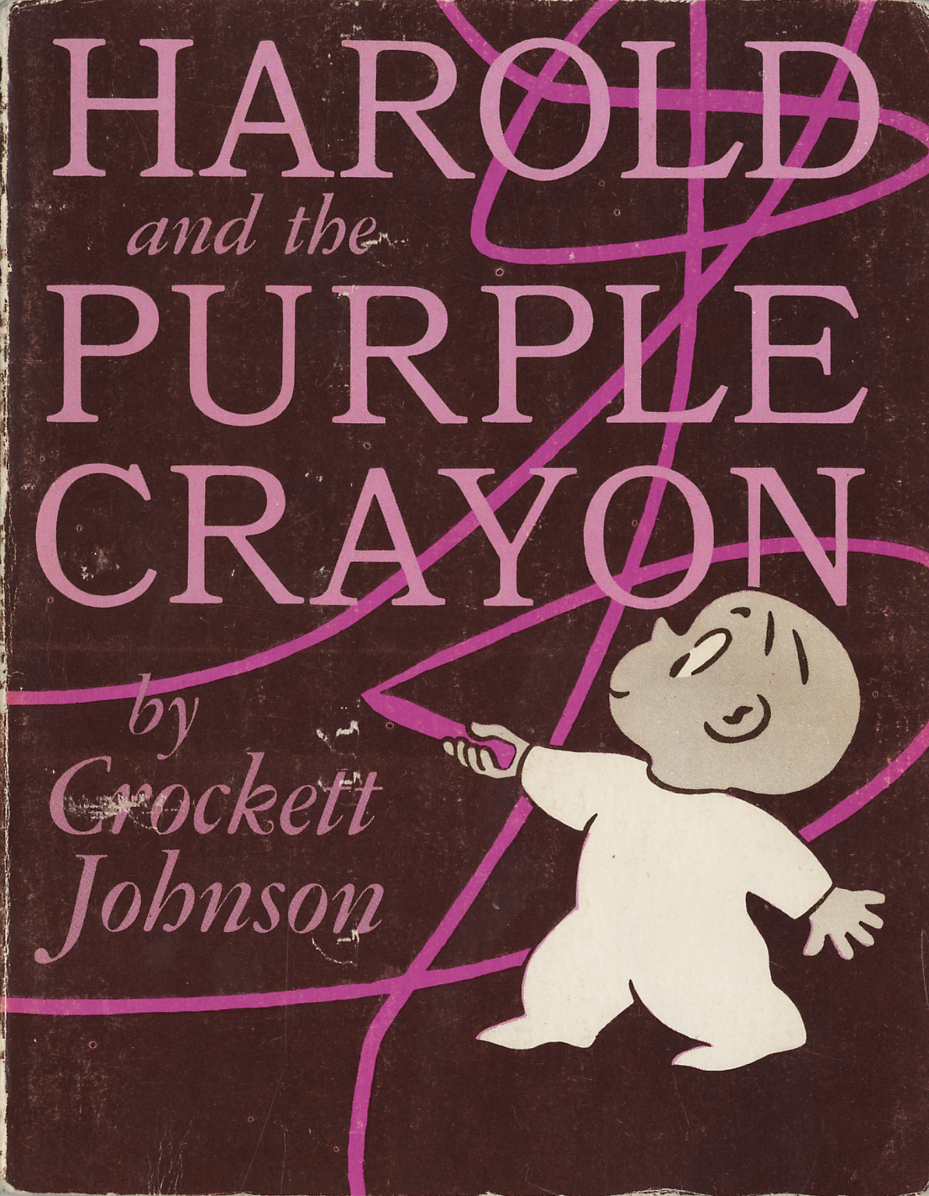

Crockett Johnson, the Harold series (1955-1963):

Crockett Johnson, the Harold series (1955-1963):

- Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955)

- Harold’s Fairy Tale (1956)

- Harold’s Trip to the Sky (1957)

- Harold at the North Pole (1958)

- Harold’s Circus (1959)

- A Picture for Harold’s Room (1960)

- Harold’s ABC (1963)

Quite possibly the best children’s books ever written, and certainly the most succinct expression of the power and peril to be found in the imagination. When I talk to people about Johnson‘s Harold books, they either (a) have not heard of them, or (b) know them and love them. Very rarely do I meet someone who knows the books, but is indifferent. In sum, if you do not know these, you should. Start with Harold and the Purple Crayon and Harold’s ABC.

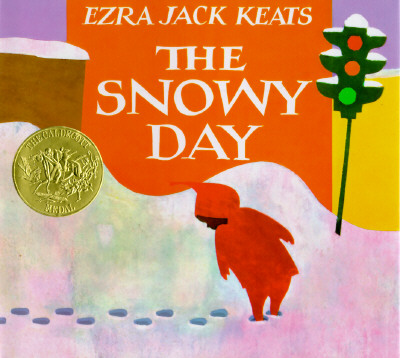

Ezra Jack Keats, The Snowy Day (1962)

This Caldecott-winning book is a favorite from my childhood. Yes, Peter (the book’s protagonist) was the first child of color I had met in literature. But what left a longer, more lasting impression was the affinity I felt – and feel – for him. As I was, Peter is a contemplative, curious child. He makes snow angels, he explores his neighborhood, discovers that his feet can make different kinds of tracks in the snow, and pretends to be a mountain-climber. As I did, he (or so it seemed to me then) often feels more comfortable in the company of his imagination than in the company of other children. He does not join in the snowball fight. After the day is over, he reflects on his adventures. The bold colors of Keats’s collages, and the thoughtfulness – the inwardness – of his protagonist make The Snowy Day a great book for any child who, like Peter, sees in snow a sense of wonder and possibility.

This Caldecott-winning book is a favorite from my childhood. Yes, Peter (the book’s protagonist) was the first child of color I had met in literature. But what left a longer, more lasting impression was the affinity I felt – and feel – for him. As I was, Peter is a contemplative, curious child. He makes snow angels, he explores his neighborhood, discovers that his feet can make different kinds of tracks in the snow, and pretends to be a mountain-climber. As I did, he (or so it seemed to me then) often feels more comfortable in the company of his imagination than in the company of other children. He does not join in the snowball fight. After the day is over, he reflects on his adventures. The bold colors of Keats’s collages, and the thoughtfulness – the inwardness – of his protagonist make The Snowy Day a great book for any child who, like Peter, sees in snow a sense of wonder and possibility.

Laurie Keller, The Scrambled States of America (1998)

I thought Emily might like to learn a little bit about the country where her mother was born. Well, that was part of the reason behind choosing this one. Mainly, I think Keller’s work is hilarious. Sure, there’s a geography lesson here, but there are far more jokes.

Jon Klassen, I Want My Hat Back (2011)

A masterpiece of economy and wit. Each detail works perfectly. And its deadpan humor knocks me out each time I read it.

Ruth Krauss and Crockett Johnson, The Carrot Seed (1945)

A little boy plants a carrot, everyone keeps saying “it won’t come up,” but every day he keeps “sprinkling the ground with water.” This story has been interpreted as being about faith, persistence, or simply ignoring the nay-sayers. Maurice Sendak calls it a “perfect picture book.”

Karla Kuskin, Roar and More (1956)

Poet Karla Kuskin’s first children’s book. Dynamic layout and typography introduces animals and the sounds they make. Visually compelling, fun to read aloud, and nice humor (she also provides the sounds of giraffe and fish).

Munro Leaf & Robert Lawson, The Story of Ferdinand (1936)

I expect you know this one, but, if not, then you might like to read my earlier post, “Ferdinand at 75.”

Three versions of three pigs:

Three versions of three pigs:

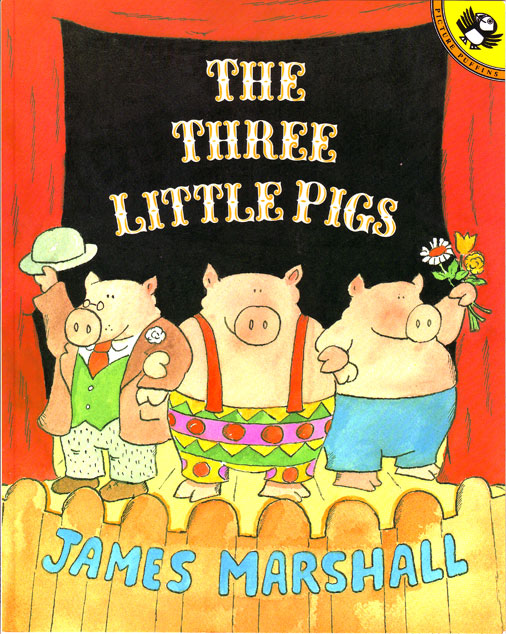

- James Marshall, The Three Little Pigs (1989)

- Jon Scieszka & Lane Smith, The True Story of the Three Little Pigs by A. Wolf (1989)

- Eugene Trivisas & Helen Oxenbury, The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig (1993)

Three versions of the fairy tale. Marshall’s stays closest to Joseph Jacobs’ original, but his illustrations add great comic timing and general daffiness. Scieszka and Smith tell the story from the wolf’s point of view. Trivisas and Oxenbury swap the roles of protagonist and antagonist. Note: be careful of what edition you get of the Marshall. There’s a re-formatted hardcover version you want to avoid.

Bill Martin, John Archambault, & Lois Ehlert, Chicka Chicka Boom Boom (1989)

Bold colors, swinging verse, and … the alphabet! One of several ABC books I’ve given thus far. See also Dr. Seuss’s ABC and Crockett Johnson’s Harold’s ABC.

Mark Newgarden and Megan Montague Cash, the Bow-Wow board books (2007-2009):

- Bow-Wow Naps by Number (2007)

- Bow-Wow Orders Lunch (2007)

- Bow-Wow Hears Things (2008)

- Bow-Wow Attracts Opposites (2008)

- Bow-Wow 12 Months Running (2009)

- Bow-Wow’s Colorful Life (2009)

|

|

|

|

|

|

I’ve written an entire post on Newgarden and Cash’s Bow-Wow books. The first, Bow-Wow Bugs a Bug, is listed in tomorrow’s post on wordless picture books. During her first year, the Bow-Wow board books have been Emily’s favorites.

Antoinette Portis, A Penguin Story (2009)

Penguin seeks something new,… and finds it! Love Portis’ graphic style, humor, and how she honors the title character’s curiosity.

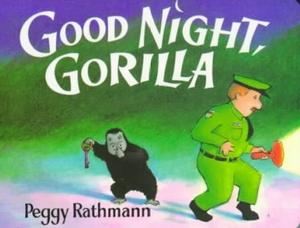

Peggy Rathmann, Goodnight Gorilla (1994)

A clever riff on Brown and Hurd’s Goodnight Moon. Rathmann has great comic timing, knows how to let the illustrations tell the story, and includes lots of fun details. The baby giraffe has a toy giraffe, the baby elephant has a toy Babar, and the baby armadillo has … a toy Ernie. Why would the little armadillo have not a toy armadillo, but the Muppet from Sesame Street? Well, why not?

Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury, We’re Going on a Bear Hunt (1989)

Exemplifies the dynamic relationship between words and images that sustains any good picture book. And it’s a fantastic read-aloud. For more Oxenbury, see the entry for James Marshall (above) – it contains three versions of “The Three Little Pigs,” one retold by Trivias and Oxenbury.

Amy Krouse Rosenthal & Tom Lichtenheld, Duck! Rabbit! (2009).

Based on the metapicture that fascinated Wittgenstein, two unseen persons debate whether we’re looking at a duck… or a rabbit.

Dr. Seuss, Green Eggs and Ham (1960)

Dr. Seuss, Green Eggs and Ham (1960)

Using only 50 different words, Seuss creates a nonsensical classic & his own best-seller. See also an earlier blog post on this book.

Dr. Seuss, Dr. Seuss’s ABC (1963)

The third of Seuss’s alphabetically themed works. The first two are The Cat in the Hat Comes Back (1958) and On Beyond Zebra! (1955).

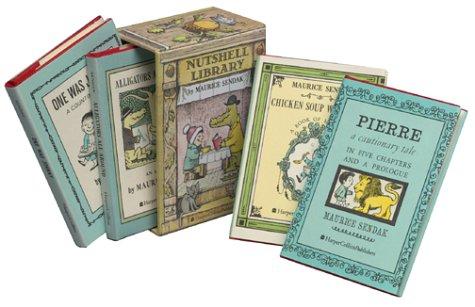

Maurice Sendak, The Nutshell Library (1962)

A collection of four books: Alligators All Around, Chicken Soup with Rice, One Was Johnny, and Pierre. All are made for tiny hands, and are what Sendak was working on just before he created Where the Wild Things Are (1963). In other words, this is prime Sendak. Wild Things will be a future purchase for Emily, but these seemed a better fit for her first year.

Esphyr Slobodkina, Caps for Sale (1940).

A peddler, a nap, and monkeys. The repetition, the bright colors, and the satisfying resolution have helped this book endure for the last seventy years.

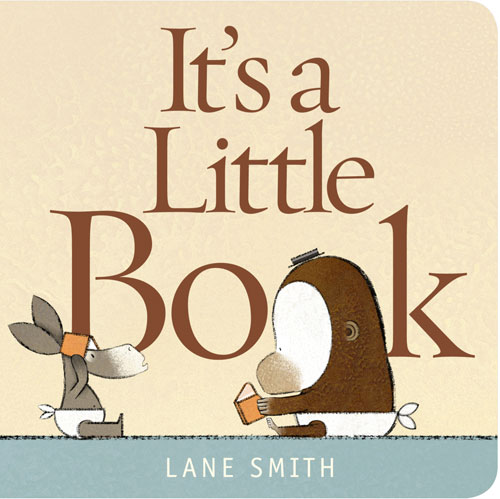

Lane Smith, It’s a Little Book (2011)

For the board book version of the picture book It’s a Book (2010), Smith tones down the joke at the end. He makes other changes (the three main characters are all much younger, for example), but retains much of the original’s sense of humor and mischief. For more Smith, see my longer blog post on him, and the entry for James Marshall (above) – it contains three versions of “The Three Little Pigs,” one retold by Scieszka and Smith.

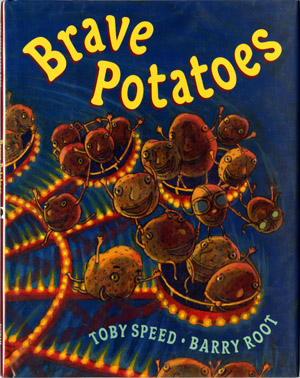

Toby Speed & Barry Root, Brave Potatoes (2000).

Toby Speed & Barry Root, Brave Potatoes (2000).

Why is this book out of print? It’s one of the best children books published in the new millennium. A verse tale of vegetables and revolution. The poetry pops, and the pictures make the “death-defying spuds” seem almost human. Vegetables of the world, unite! See also my tongue-in-cheek post on this book for Lane Smith & Bob Shea’s blog.

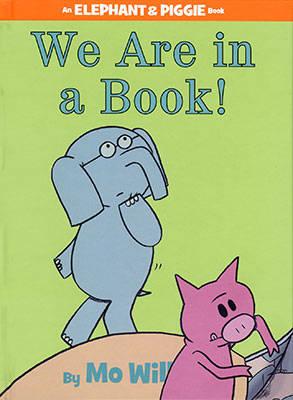

Jon Stone and Michael Smollin, The Monster at the End of This Book (1971)

Thus far, the sole Little Golden Book on this list. Grover (the Muppet) is worried that he’s going to face a monster at the end of the book, and pleads with the reader to help him. Metafictional humor for beginning readers. See also Mo Willems’ Elephant and Piggie: We Are in a Book (scroll down).

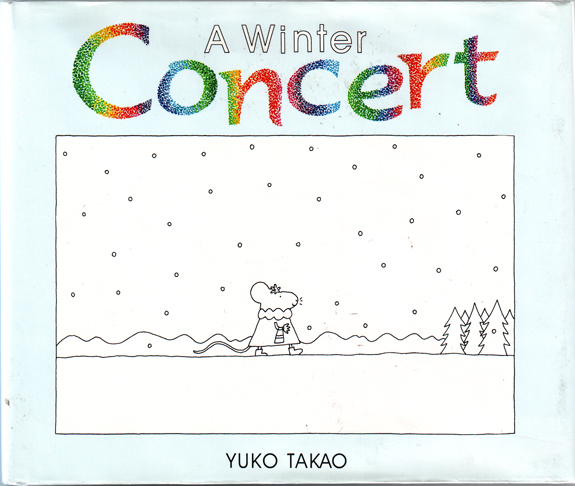

Yuko Takao, A Winter Concert (1995, trans. 1997)

Yuko Takao, A Winter Concert (1995, trans. 1997)

Along with Burton’s Katy and the Big Snow and Keats’ The Snowy Day, this was part of a trio of winter-themed books I sent Emily in late October 2011. Rendered in black lines on white paper, a mouse goes to a concert, where she hears “beautiful music” (rendered in small colored dots), which she and the other concert-goers carry home with them – brightening the wintry landscape. An evocative sense of how music transforms experience. See also my brief blog post on the book.

Shaun Tan, The Lost Thing (2000)

A modern classic about paying attention, and what happens when we don’t. Later adapted into an Academy Award-winning short film, this book is probably for slightly older children (early grade school, rather than pre-school), but Tan is one of the greatest narrative artists working today – and I thought it important for Emily to have his work in her library. Also, it’s visually rich, with much to reward rereading.

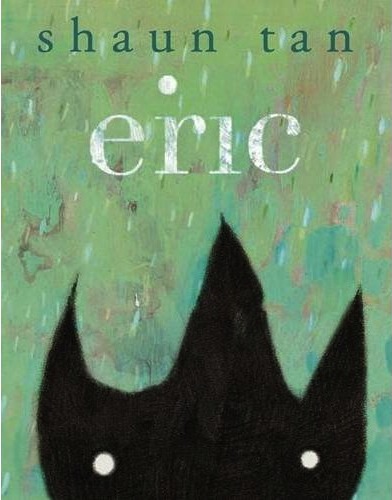

Shaun Tan, Eric (2010)

Shaun Tan, Eric (2010)

When a foreign exchange student stays with a family, they try to make him welcome. But what does he think of them? A slightly different version of the story in Tales from Outer Suburbia (2008), this has Tan’s sense of mystery, wonder, and warmth. If there’s a Tan story for the youngest readers, this – despite its more “advanced” vocabulary – is the one.

Martin Waddell and Barbara Firth, Can’t You Sleep, Little Bear? (1988)

This book launched Waddell and Firth’s Little Bear series (no relation to the Little Bear books by Else Homelund Minarik and Maurice Sendak). A gentle tale, in which big bear helps little bear face his fear of the dark, and get to sleep.

Ellen Stoll Walsh, Mouse Paint (1989)

The pleasure of combining colors, transformation, and evading the cat. The sharp contrast between colors appeal to the eye.

Mo Willems, Don’t Let the Pigeon Ride the Bus! (2003)

Perfect illustration of the “less is more” principle of storytelling. Altering the background color to reflect the title character’s changing mood, Willems provides just enough detail to convey the pigeon’s character – and nothing more. Sympathetic to a child’s desire to be in charge and a great read-aloud, Willems’ book never fails to amuse me.

Mo Willems, Knuffle Bunny: A Cautionary Tale (2004)

The book that gave us the phrase “aggle flaggle klabble” and the term “to go boneless” (as in “She went boneless”).

Mo Willems, Elephant & Piggie: We’re in a Book! (2010)

Metafictional tale about reading, starring Willems’ duo. My favorite of the Elephant & Piggie books, and a worthy companion to Stone and Smollin’s The Monster at the End of This Book (see above).

Looking for other great children’s books? Try these blogs:

- Elizabeth Bird’s Fuse #8

- Julie Walker Danielson’s Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast

- Anita Silvey’s Children’s Book-a-Day Almanac

Related posts on Nine Kinds of Pie:

- How to Find Good Children’s Books (April 2011)

- Desert Island Picture Books (Oct. 2011)

- Mock Caldecott, 2011: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2011)

- Mock Caldecott, 2010: Manhattan, Kansas Edition (Dec. 2010)

- Bow-Wow! (May 2011)

- Ferdinand at 75 (Sept. 2011)

- Green Eggs and Ham: A 50-Word Book Turns 50 (Aug. 2010)

- It’s a Lane Smith Book (Aug. 2010)

- “Too bad his duck is so crazy”: Tim Egan, Seriously Funny (Aug. 2010)

- Vandalizing James Marshall (Apr. 2011)

Jessica Young

Anne

Philip Nel

Ariel Cooke

Anne

Nancy

Philip Nel

Kristin McIlhagga

Toby Speed