Welcome to day 2 of my unashamedly idiosyncratic coverage of the 2014 San Diego Comic-Con. Let’s start with a little cosplay, shall we?

Cosplay!

One could spend all day photographing people in their costumes. I didn’t. These (above) are just a few I happened to catch. Instead, I went to panels, such as:

Charles Schulz and Social Commentary in Peanuts

This panel featured a presentation by Corry Kanzenberg (at left, curator, Charles M. Schulz Museum). Panel discussion followed with her, and (left to right): moderator Tom Gammill (The Simpsons, Futurama, Seinfeld), Art Roche (content director, Charles M. Schulz Creative Associates), and Seth Green (Robot Chicken, Family Guy, Buffy the Vampire Slayer).

At the moment the panel begins, Seth Green arrives (right on time!), and – during the brief conversation after the panelists introduce themselves – Green recalls a phone call from Jeannie Schulz (Charles M. Schulz’s widow) after Robot Chicken had done an episode in which they killed off all the Peanuts characters. Green was worried that he’d be in trouble. Instead, Jeannie was phoning to say “that sort of humor was exactly the sort of stuff that Sparky would have liked.” Green was so moved, he says, that he “started crying.”

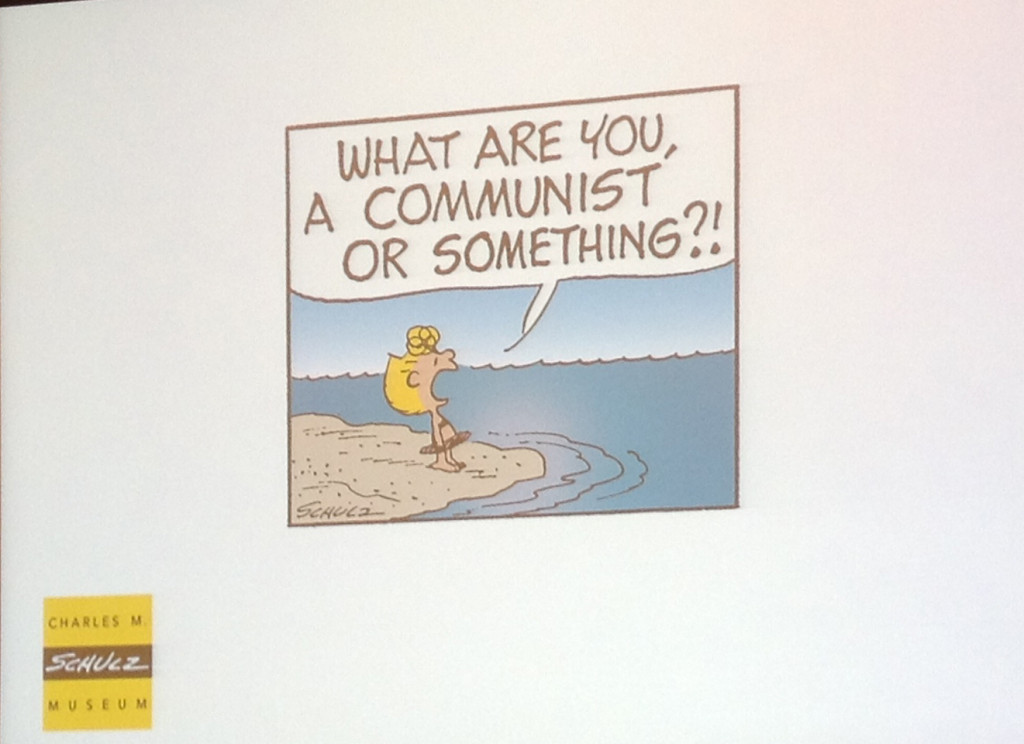

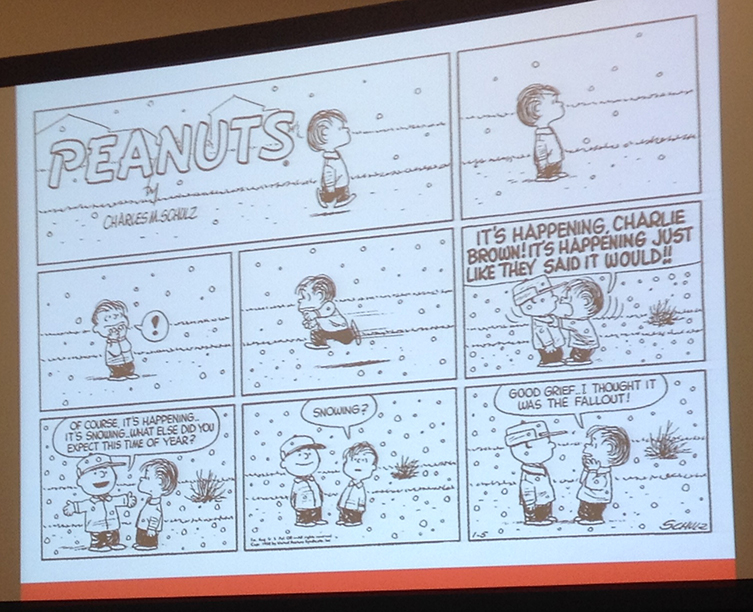

Then, Corry Kanzenberg’s presentation, in which she shows such strips as this one, in which Linus mistakes snowflakes for nuclear fallout.

Politically, Corry says, Schulz’s politics were “kind of middle of the road.” Indeed, in the case of one strip that mentions school prayer – one of the most controversial Peanuts strips (from, I think, 1963) – Schulz received lots of requests from both sides of the issue, asking to reprint the strip. He denied them all, because he didn’t want to appear to be taking sides.

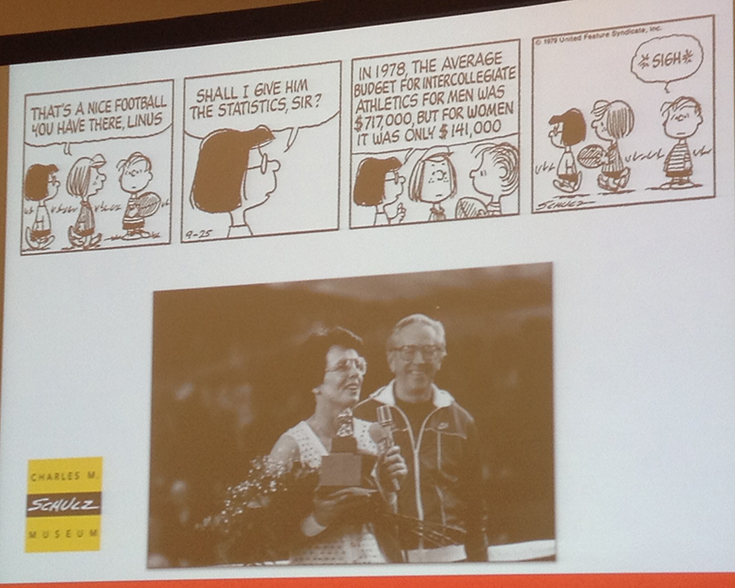

However, at times, he was willing to take more of a stand – such as, in 1968, when he integrated Peanuts, introducing the character Franklin. He also took a stand in advocating for Title 9, as (a) seen in this strip and (b) suggested by this photo of Schulz and Billie Jean King.

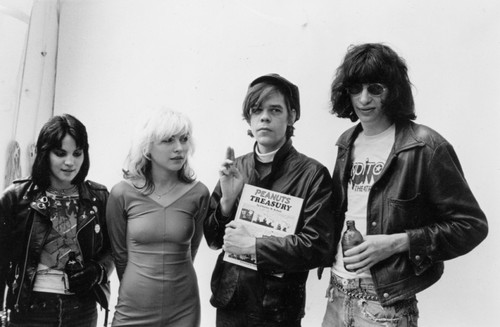

As I side note, I really loved this photo with Joan Jett, Debbie Harry, David Johansen, & Joey Ramone.

The story is that it was a mock wedding between Debbie Harry & Joey Ramone, and they used the Peanuts Treasury as the Bible.

During the panel discussion, Art Roche (the licensing-and-marketing guy) says, “People always want to put Peanuts on whatever case they have.” For example, “We just had the World Cup. There were several countries want to put the Peanuts characters in their World Cup uniform. And that’s OK. And there are other cases where they want to put the Peanuts characters in religious shrines,… and that’s not O.K.”

Seth Green observed, “As you all did, I grew up on Peanuts. It seemed so soft from the outside, but underneath, it’s incredibly thought-provoking.”

Hilarious moment: Fred Tatasciore (who plays the Hulk on the Hulk and the Agents of S.M.A.S.H. cartoon) does the Miss Othmar/adult Peanuts voice and asks the panel an (incomprehensible) question. Seth answers the question straight, as if he understood it. Tatasciore asks a second question, and Seth again answers as if it were perfectly normal. Tatasciore does an adult-speak incomprehensible thank-you & yields the floor. Seth then explains to us that we’d just been listening to Fred Tatasciore.

A few other interesting facts I learned:

- Schulz created 17,897 Peanuts strips.

- At its height, Peanuts was published in 2600 newspapers, and 75 countries — making it one of the most successful comic strips ever.

- In Japan, Woodstock is very popular — so much so that people know the names of Woodstock’s friends. Harriet, Olivier, Conrad.

Comic Arts Session #3: British Comics, Genre, and the Special Relationship with American Comics

To quote the panel description, “Chris Murray (University of Dundee) discusses the often-overlooked and peculiar history of British superheroes, arguing that they reflect the changing relationship between the two countries in the aftermath of World War II. Julia Round (Bournemouth University) investigates the use of gothic and horror tropes in British girls’ comics of the 1970s and 1980s, which, she argues, draw on some of the tropes of the previous generation of American horror comics. Phillip Vaughan (Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design) analyses British science fiction comics in terms of the influence from American comics, and considering their relationship to British and American television and film.”

Chris Murray, who is writing a book on British superheroes, gave a fascinating talk.  I knew nearly nothing about British superheroes – save for, say, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ versions of American superheroes (in Watchmen). His argument is that British superheroes “are based on the British political relationship with America.”  He noted that the superhero “is such a perfect icon for America, as the American empire is taking off.”  At the same time that’s happening, “the British empire is in sharp decline,” as its place in world history is being taken over by America.  As a result, “there’s an ambiguous, tense, relationship with America.”

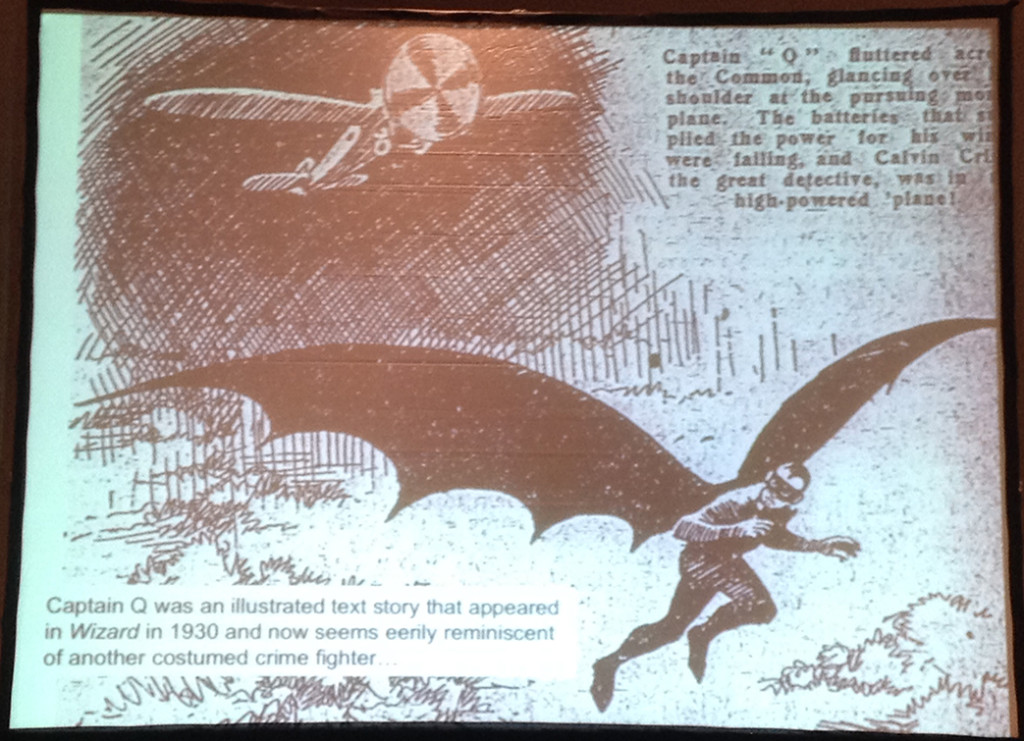

Most of the lines of influence come from America, but there are the occasional images from British strips – such as this one, from Captain Q –Â that do make you wonder if there were any trans-Atlantic influence going in the other direction.

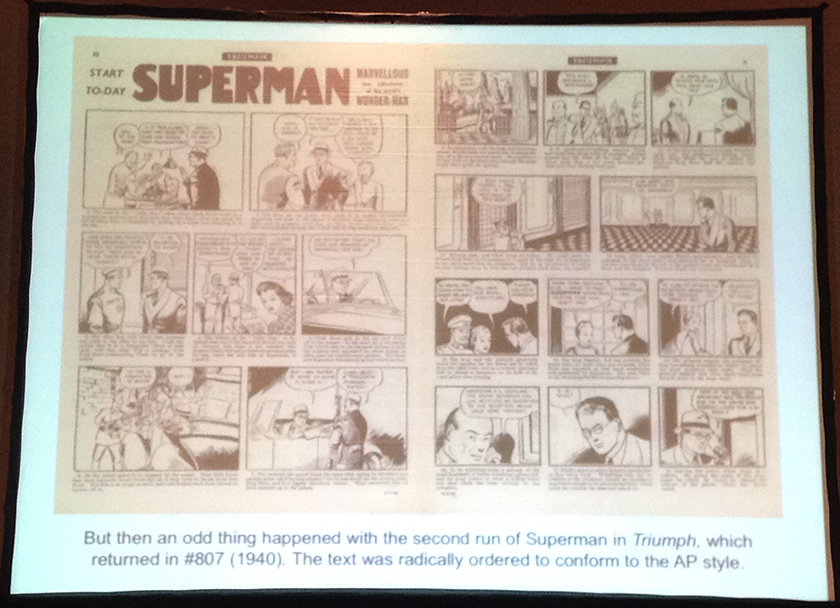

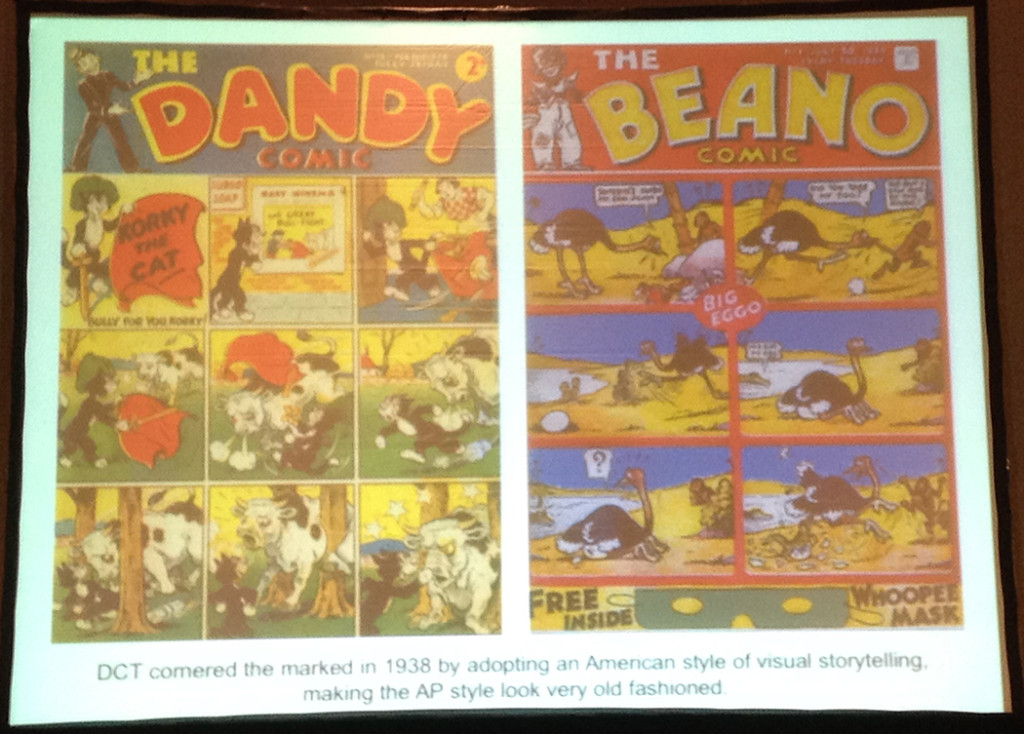

I was interested to learn that British comics tended to have pictures and a lot of text. Indeed, sometimes when they adapted American comics for the British market, they’d add lots of text! This text-heavy style became known as the Amalgamated Style (because Amalgamated Press favored it).

Murray noted that American comics were much more visually sophisticated, adding that British comics like Dandy and Beano succeeded because they copied American comics’ visual style.

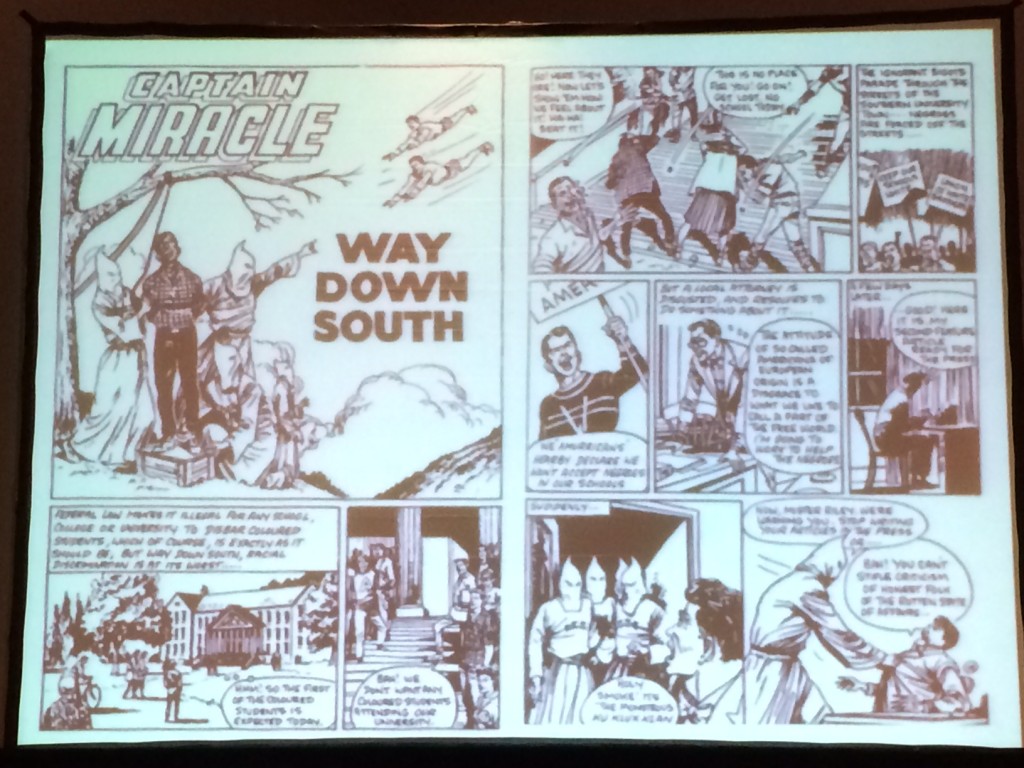

This Captain Miracle comic strove so ardently to convey that it was American that – as its subject – it faced racism in the American south.

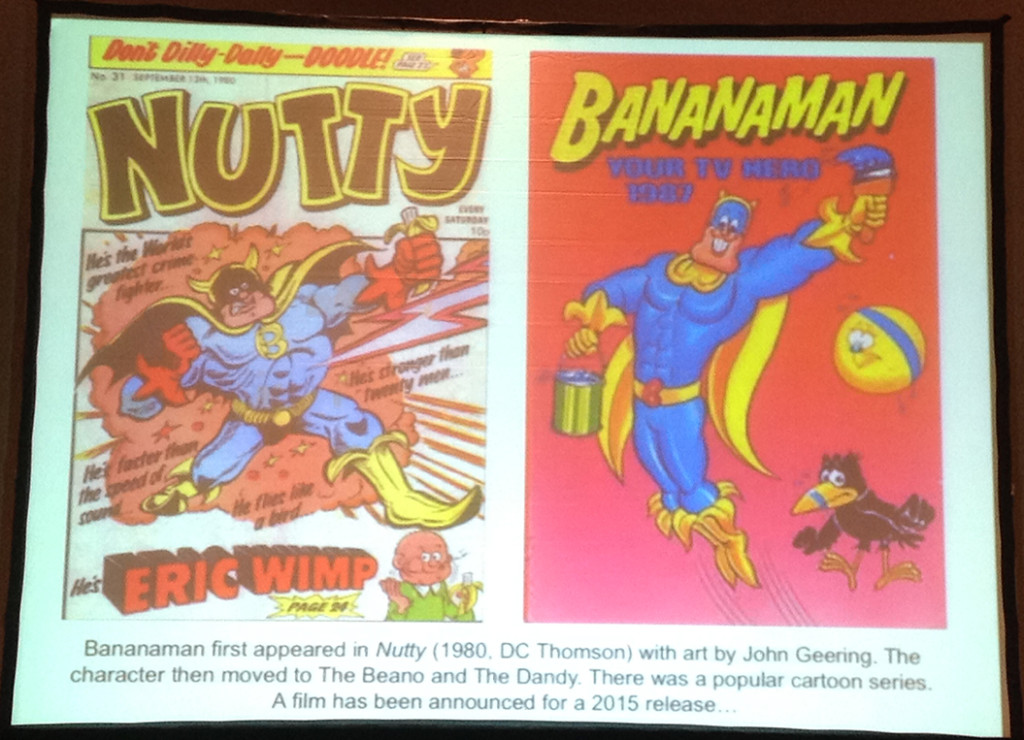

There’s also a strain of British superhero comics that don’t take themselves too seriously, such as Bananaman, who gets his superpowers from… bananas?

Fascinating stuff. Â This is going to make a great book!

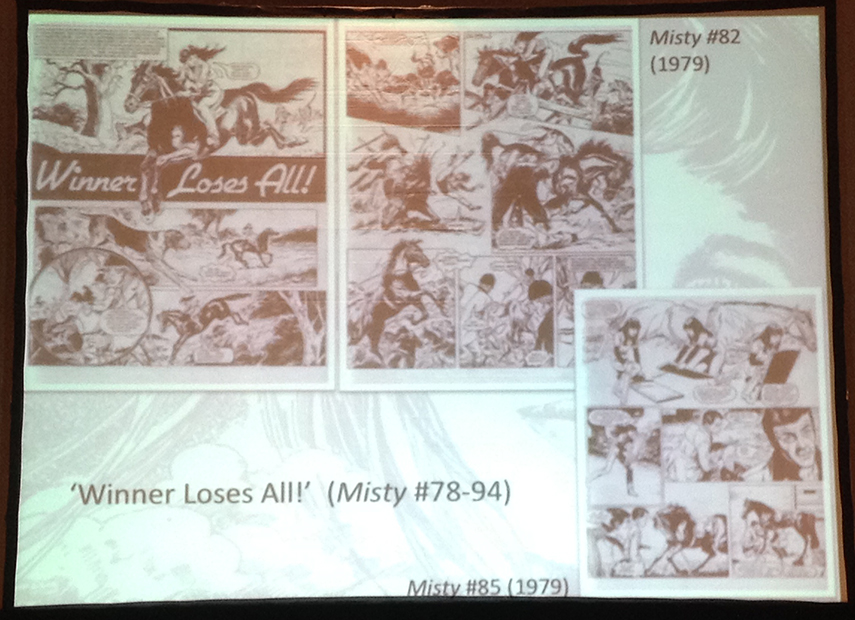

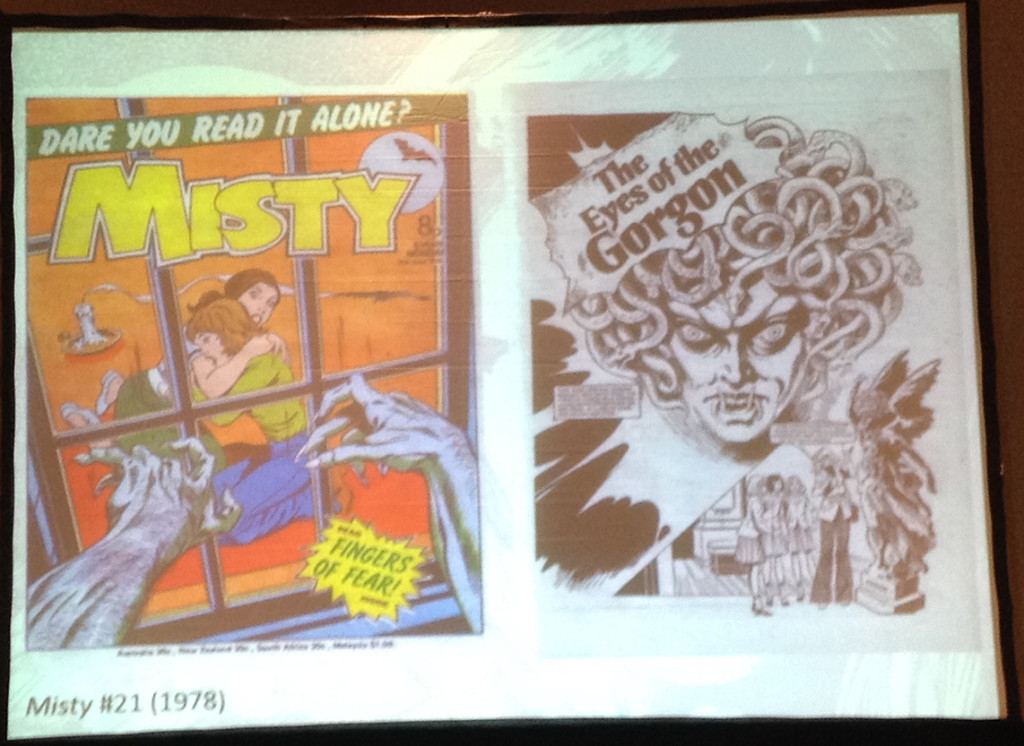

Julia Round‘s focus was Misty – an anthology comic for girls (1978-1980), which has been described as a “female 2000 A.D.“

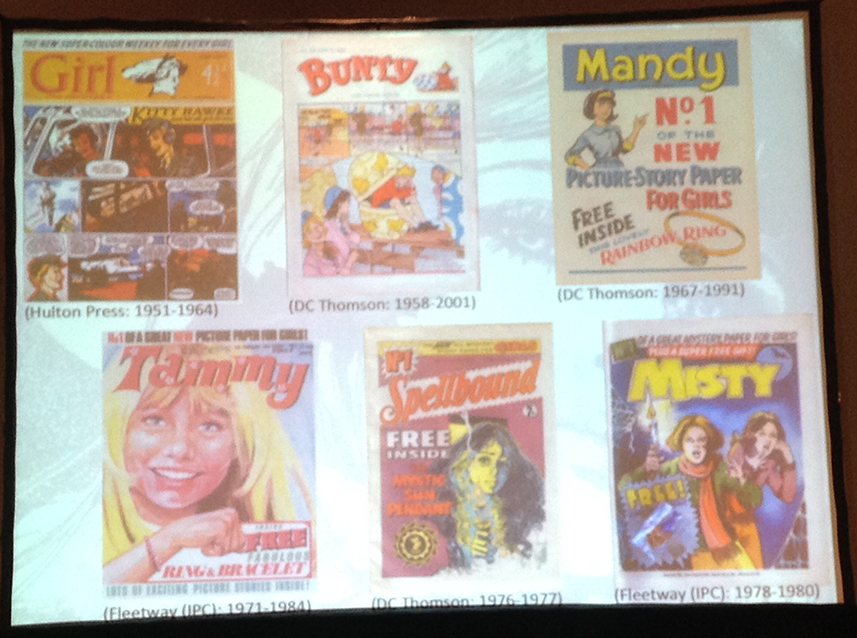

She gave us an intriguing history of girl comics in Britain.  These start in the 1950s, featuring girls all in “gender-approved occupations. I was particularly interested by the long-running “Four Marys,” which ran in Bunty.  It featured four different Marys, each of different social class, at boarding school.

The tales of peril in Misty seem to be a response to these earlier ones. Such tales, she says, are “not new in girls’ comics, but there is a darker, more mystical turn here [in Misty].”  She in particular praised the tension between moral content and ironic comment in Misty because there were “no comforting conclusions here”

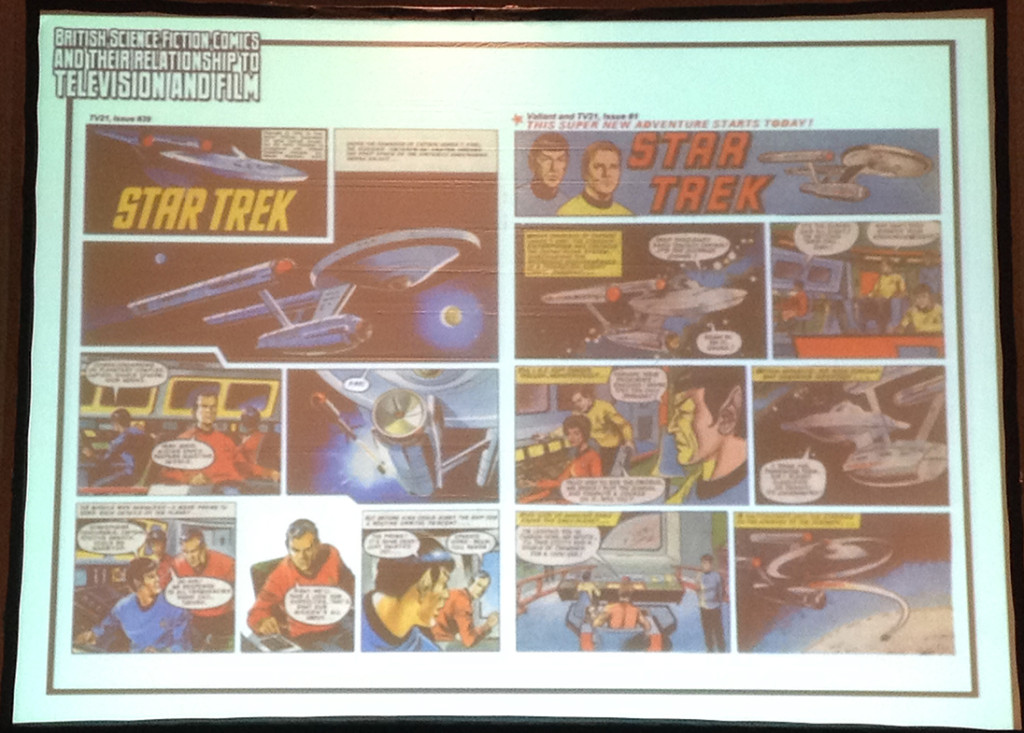

Phillip Vaughan‘s paper was:

He assembled a great collection of information on the subject, and had lots of slides to share. To be frank, he is, I think, still working out what story he wants to tell about this material.  And that’s fine.  But one result, for me, was that I was wondering: What’s the narrative of this history? I hope that my saying this doesn’t come across as overly nit-picky or critical. I’m very familiar with this struggle. It’s the central task of the biographer, too.

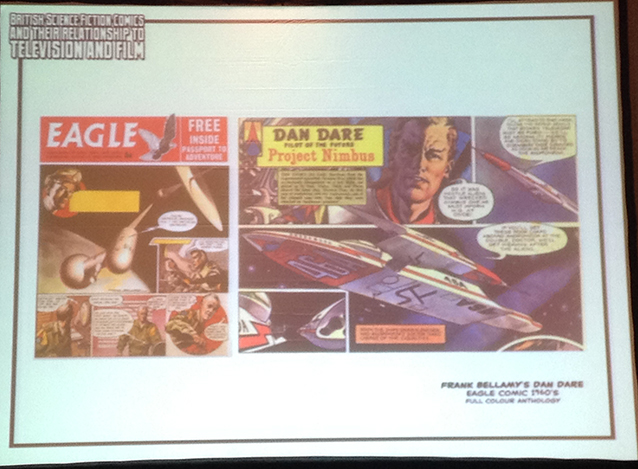

And, as I say, he presented great information in very elegant slides. For instance, he told us that one British response to American horror comics was Dan Dare, a very stiff-upper-lip pilot of the future.

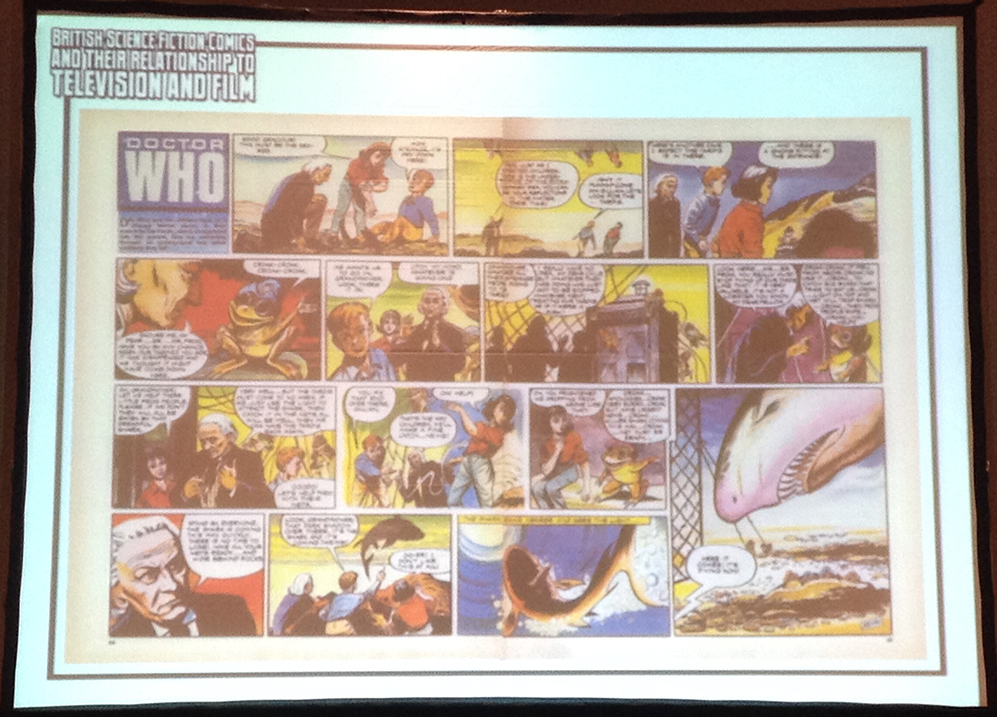

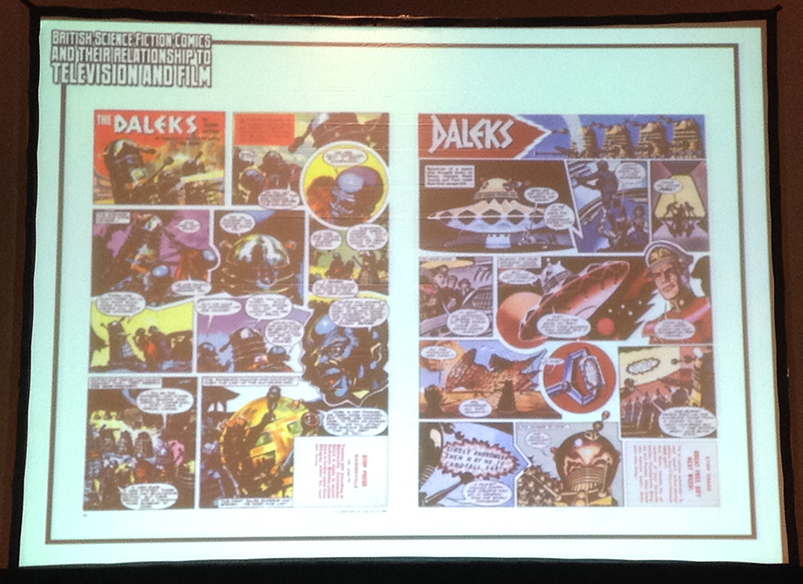

Here are a couple of comics based on the TV show Dr. Who.  The show, he noted, had a limited budget.  In contrast, the comic could depict more.

There was also a UK strip based on Star Trek. The strip, created by UK writers and artists, “had a different flavour.”

Gene Luen Yang in Conversation with Scott McCloud

The panel description is “Comic-Con special guest Gene Luen Yang (The Shadow Hero) and Scott McCloud (Understanding Comics) talk comics, creative processes, current and upcoming projects, and the general state of the industry. It’ll be awesome.” But Scott McCloud stressed that the focus here was on Yang, not on himself (or on them both equally) – McCloud had a panel later that day devoted to his new book.  Sadly, I had to go to a signing & so missed that panel.

But… I did attend this one! Â Here are my notes. Â (I would write them up in to something more coherent, but this account is taking longer than I thought it would! Â Apologies…)

Gene Luen Yang: This is surreal for me. Scott McCloud is one of those seminal voices in my childhood. … If you had told 19-year-old me that I’d be on this panel with Scott McCloud, my head would have exploded.

Scott McCloud: One question on Boxers & Saints. [McCloud shows slide of book where they’ve been put in the box in the wrong order, so that the spines do not form a face.] Do you ever just want to punch anyone who puts it in like that ?

GLY [joking]: The last time I punched someone, actually, was…”

SM: You’ve been making comics for about 15 years…?

GLY: I’ve been making comics ever since I read Understanding Comics.

McCloud will be editor of next (2015, I presume?) Best American Comics….

Gene Luen Yang’s latest is the Shadow Hero — a revival of a the first Chinese-American superhero comic. But, Yang tells us, the comic’s original publisher didn’t agree to allow the protagonist to be depicted as ethnically Chinese.  So, the artist who created the comic responded in a passive-agressive way.  He never showed the hero’s face.

SM: You may be one of the most unpredictable writers on the planet. … When Chin-kee showed up [in American Born Chinese], my jaw was on the floor… Â From the very beginning you were addressing Chinese-American experience, Asian-American experience, but… in such a subtle way,… “with eyes unclouded by hate.” Sorry– Princess Mononoke line.

SM: You may be one of the most unpredictable writers on the planet. … When Chin-kee showed up [in American Born Chinese], my jaw was on the floor… Â From the very beginning you were addressing Chinese-American experience, Asian-American experience, but… in such a subtle way,… “with eyes unclouded by hate.” Sorry– Princess Mononoke line.

GLY: I love that line. Â I think, especially with Cousin Chin-kee, I did that as a mini-comic, I think maybe 12 people read it, and 11 of them were people I knew. I could have called them up to explain any misunderstanding. Â I wonder if I would have done it the same way if I were doing it as a book.

SM: Who would have thought this book would have become so accepted?

GLY: There’s something about the intimacy of comics that gives you this sort of false bravado….

Yang and McCloud both praise Michael DeForge’s comics. McCloud praises Yang as a writer of prose – “that directness.  Telling a story in an unexpected way.”

SM: You’re drawn to collaboration. Why?

GLY: They’re two different experiences. Â When you’re working with someone else, you’re telling a story in a mixed voice. … With something like Boxers & Saints, it came out of my whole childhood — I grew up in a Chinese-American Catholic community. … It expressed a sense of the difference between Eastern and Western ways of looking at things that I had felt since my childhood.

Yang admits to having a bad color sense. (That’s why he had a colorist for Boxers and Saints, he says.) Scott McCloud admits same. Yang says he’s going to tell his wife so that she stops picking on him about it.

McCloud, in a slightly roundabout way, asks Yang about religion (McCloud starts with mythology)…

GLY: At the root of religion is that story is important, that story is how we as human beings organize ourselves. … Person hearing the story should have a personal relationship with that story.

GLY: Within the Bible, my favorite book is The Gospel of Mark. Â It has two endings. Â One: two women leave the tomb, they’re sad. Â Two: 16 completely ruins it. Â First is better because it’s uncertain — it leaves you to resolve it in your own life.

McCloud and Yang both admit to not having seen M. Night Shyamalan’s adaptation of Avatar the Last Airbender, though Yang offers that he’s “heard that [watching] it’s like punching yourself in the face over and over again.”  In further discussion of (what I’d call) the racist casting of Shyamalan’s Avatar, Yang says, “I don’t think I could ascribe any racism to the decision. I think it was driven by the market.”

They talk about teaching – Yang had left teaching, but is going back to teach computer science (one class per year) because he misses it.

SM: Surely, there’s a role of an educator that plays a role in your storytelling

GLY: I think I’m kind of like you in this. I’ve been called Asian Scott McCloud before. … For me, I think if I go into a story and I’m trying to deliver a message,.. I find that the story comes out anyway.

They start to talk process….

GLY: Do you outline?

SM: OK! Let’s talk shop! I do outline, and then I do super-obsessive, anal-retentive layouts…. Â How do you do it?

GLY: I’m an outliner. Â When I started out, I wanted to be more of a pantser. But I became a planner. [Pantsers flies by seat of their pants.]

SM: I wanted to be a pantser, too, but my dad was an engineer.

GLY: My dad was an engineer, too!

SM: I thought so! Â About 10 minutes ago, I was thinking: I wonder if his dad’s an engineer?

Both mention and praise Anya’s Ghost….

SM: John Green really loved Boxers & Saints…. and he doesn’t think of himself as writing for a YA audience. He thinks of himself as writing for an audience.

GLY: I don’t think comics has traditionally thought a lot about age categories.

I then had to dash out so I could get to my signing – or, to be more accurate, my “signing.”

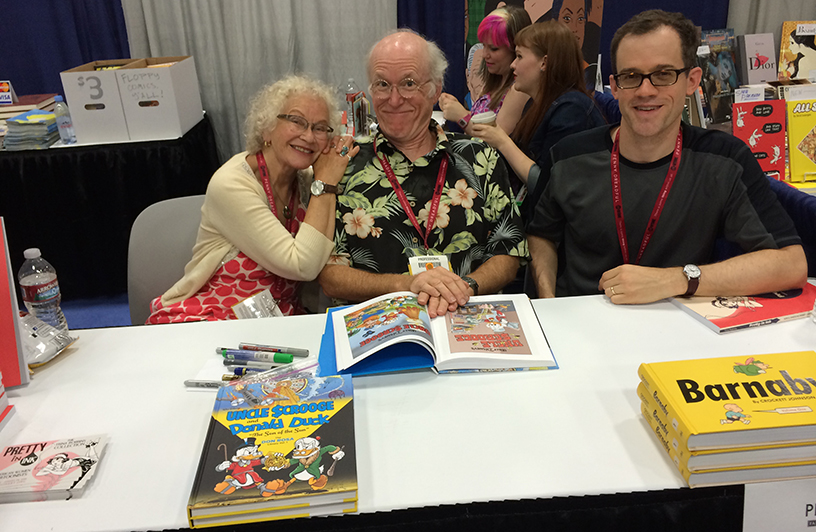

Don Rosa, Trina Robbins, and Yours Truly

From 4 to 6 pm, I sat at the Fantagraphics booth, signing copies of Barnaby Volumes One and Two. By which I mean to say: From 4 to 6 pm, I sat at the Fantagraphics booth. I enjoyed chatting with the Fantagraphics gang (Eric! Jacq! Jen! Kristy!), Bob Harvey, assorted passers-by, and – at the signing table – Trina Robbins, and Don Rosa! Trina Robbins has the original Holt hardbacks of Barnaby, and Don Rosa remembers watching the 1959 TV special (starring Bert Lahr as Mr. O’Malley, and Ronnie Howard as Barnaby).

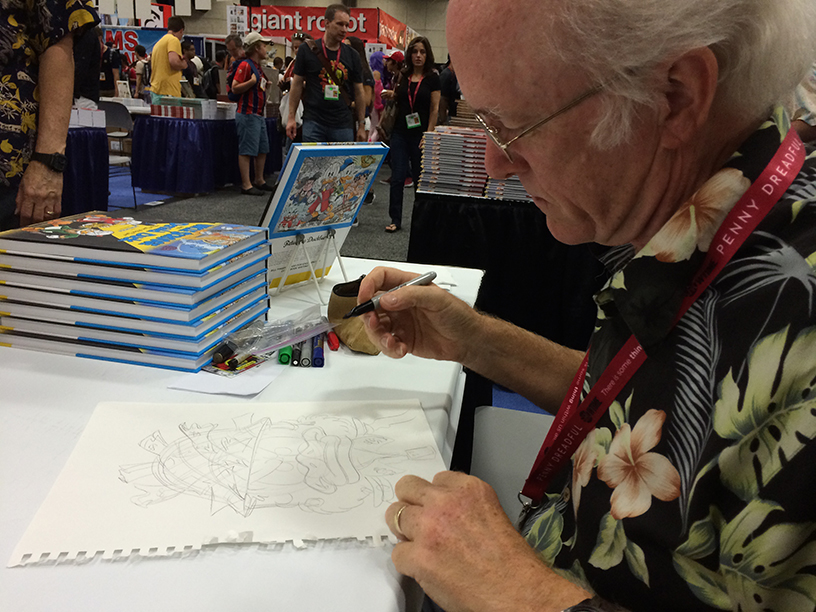

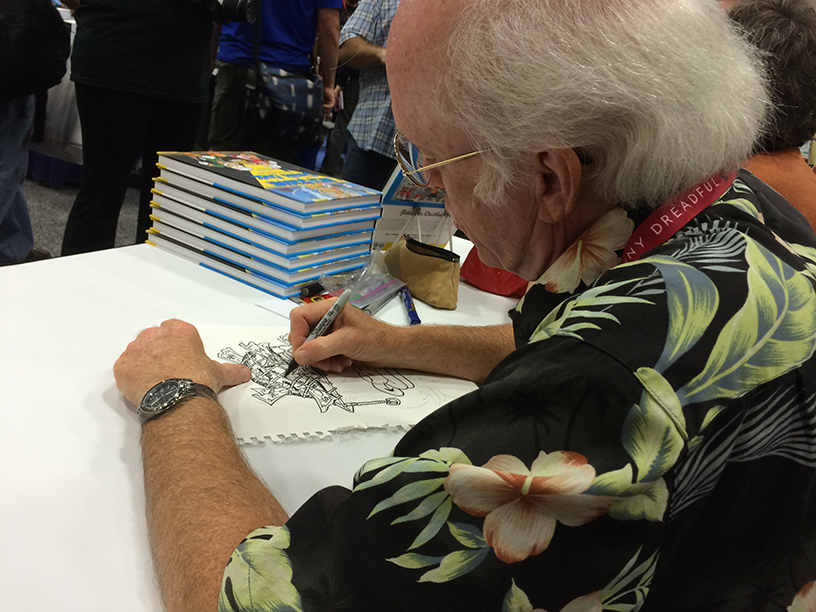

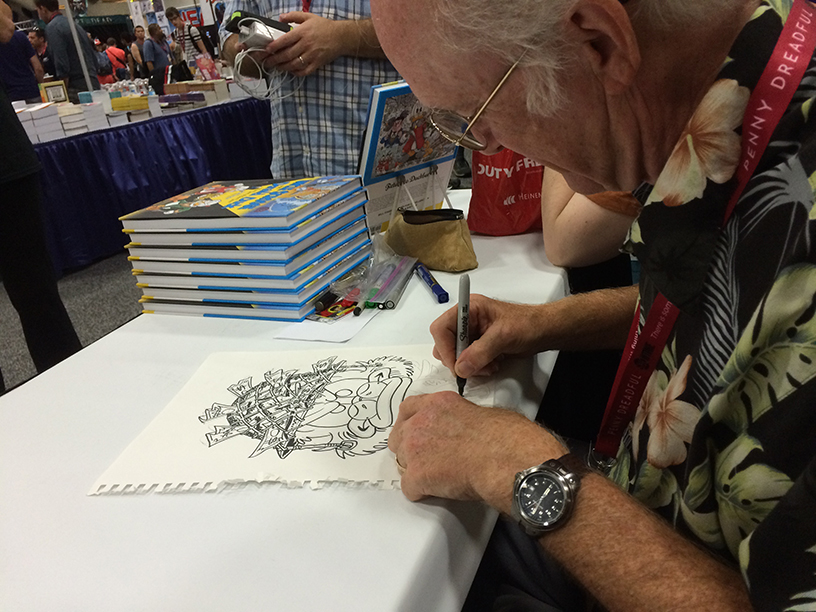

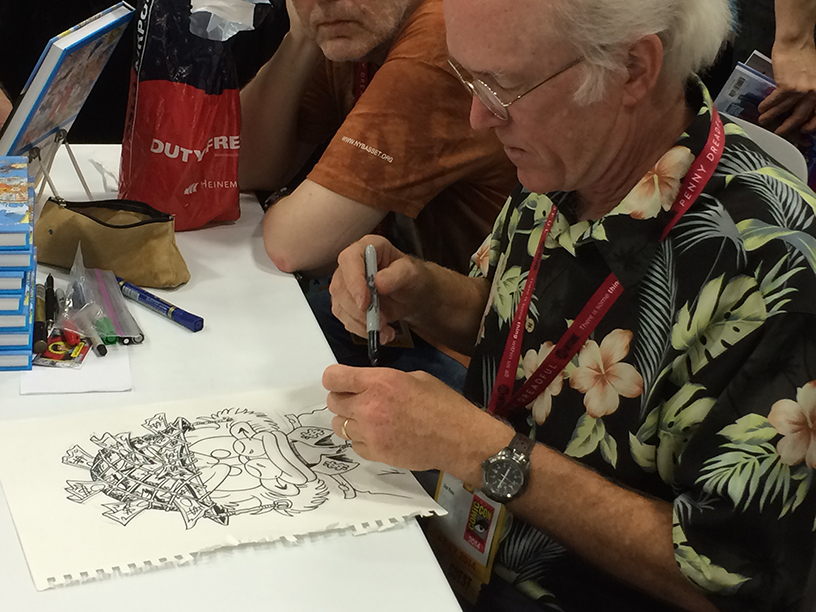

And it was really fascinating watching Don Rosa draw. Here he is drawing Scrooge McDuck for a charity auction:

He says people who watch him draw see him sketch the drawing, and then – as he draws the ink lines – see him not drawing directly on the sketched lines. “Why don’t you draw on the pencil lines?” They ask. “Those lines just tell me where not to draw,” he replies.

Sitting behind him, in the last photo, is a fan from Norway. Â No less than three Norwegian fans came up with books to sign. He also had fans from Sweden, Mexico, and various parts of the U.S. He told me he’s much more popular in Europe. Â There, fans line up for hours to get his autograph. Â Here, in the U.S. the lines aren’t as long – indeed, Europeans (especially those from the Scandinavian countries) will sometimes fly to a comics convention in the U.S. where it’s much easier to get his autograph.

He was very gracious to all the fans, inscribing their books, drawing a picture if asked. Rosa makes no profit from the sales of these books. That money all goes to Disney. But he’s glad to see his works getting reprinted here, in the U.S. And he’s glad that his friend Gary Groth’s company can profit from that a bit, too.

That’s all for tonight!  I’ll be signing (or “signing”) again at the Fantagraphics booth (#1718) between 9 and 10 am on Friday. Stop by!

Comic-Con 2014:

Comic-Con 2013: