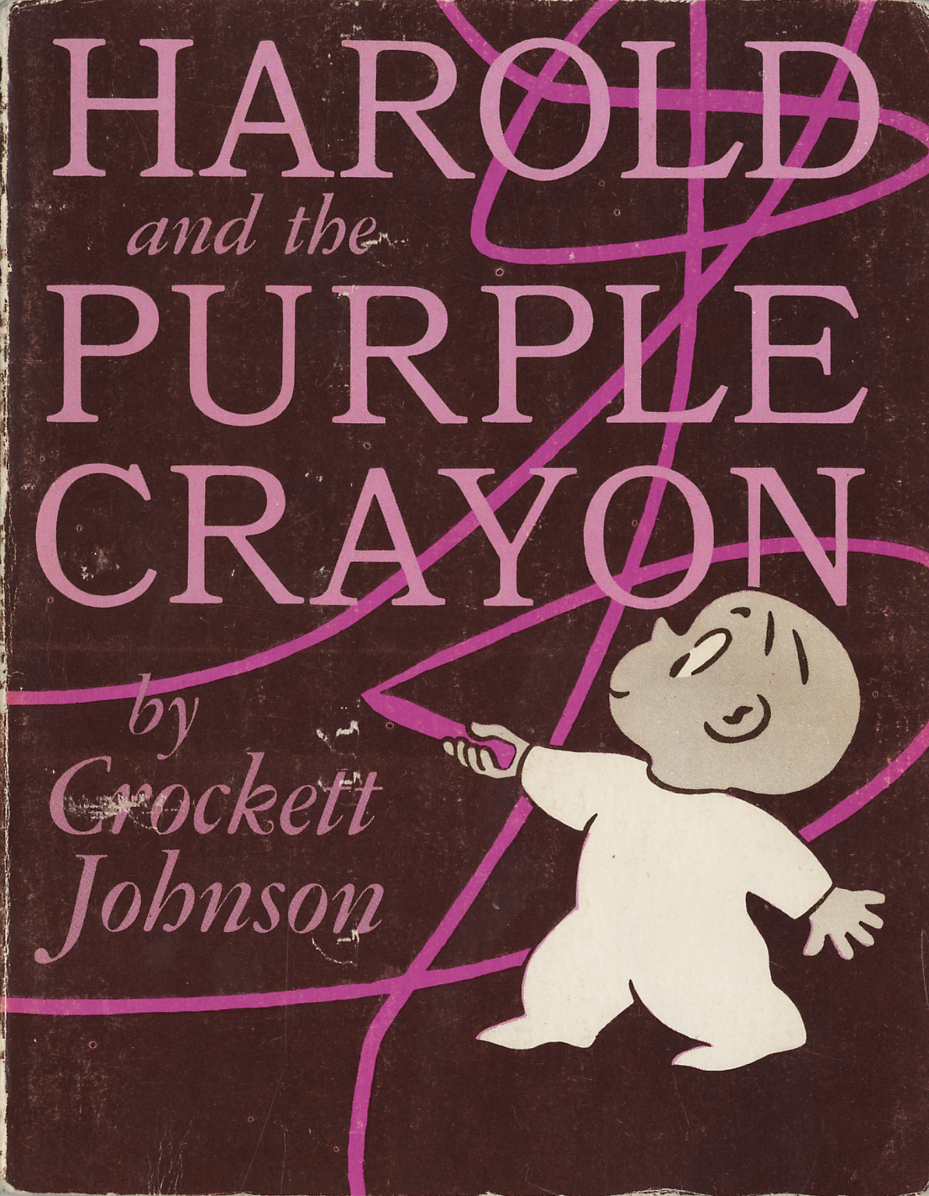

To celebrate Crockett Johnson‘s 110th birthday, I offer some advice on how to read Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955). Sort of. This is not so much “advice” as it is a glimpse of my work-in-progress, How to Read Harold: A Purple Crayon, Crockett Johnson, and the Making of a Children’s Classic. The book (when finished, and presuming anyone wants to publish it) is both a biography of a book and a succinct introduction to how children’s picture books work. Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon reveals how complex an apparently simple story can be, and offers a case study in what we miss when we underestimate, trivialize, or simply fail to look closely at the art of the picture book. Indeed, the book’s deceptively transparent aesthetic makes it ideal for this purpose because, at first glance, most people would deem the book self-explanatory. What more can be said about a boy, a crayon, and the moon?

To celebrate Crockett Johnson‘s 110th birthday, I offer some advice on how to read Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955). Sort of. This is not so much “advice” as it is a glimpse of my work-in-progress, How to Read Harold: A Purple Crayon, Crockett Johnson, and the Making of a Children’s Classic. The book (when finished, and presuming anyone wants to publish it) is both a biography of a book and a succinct introduction to how children’s picture books work. Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon reveals how complex an apparently simple story can be, and offers a case study in what we miss when we underestimate, trivialize, or simply fail to look closely at the art of the picture book. Indeed, the book’s deceptively transparent aesthetic makes it ideal for this purpose because, at first glance, most people would deem the book self-explanatory. What more can be said about a boy, a crayon, and the moon?

In what is currently 15 very short chapters (and will ultimately be perhaps 25 very short chapters), I offer different ways in thinking about one book – and, in this sense, I’m making a nod to Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik‘s forthcoming How to Read Nancy, a brilliant close-reading of a single Nancy comic strip. More than merely an expansion of their original essay, the book offers 43 ways of reading the Aug. 8 1959 Nancy and, in so doing, provides a master class in how comics work. I’m hoping to achieve something similar for picture books.

Here, then, is an extract from How to Read Harold. Enjoy!

One, Two, Three Dimensions; or, “And the moon went with him.”

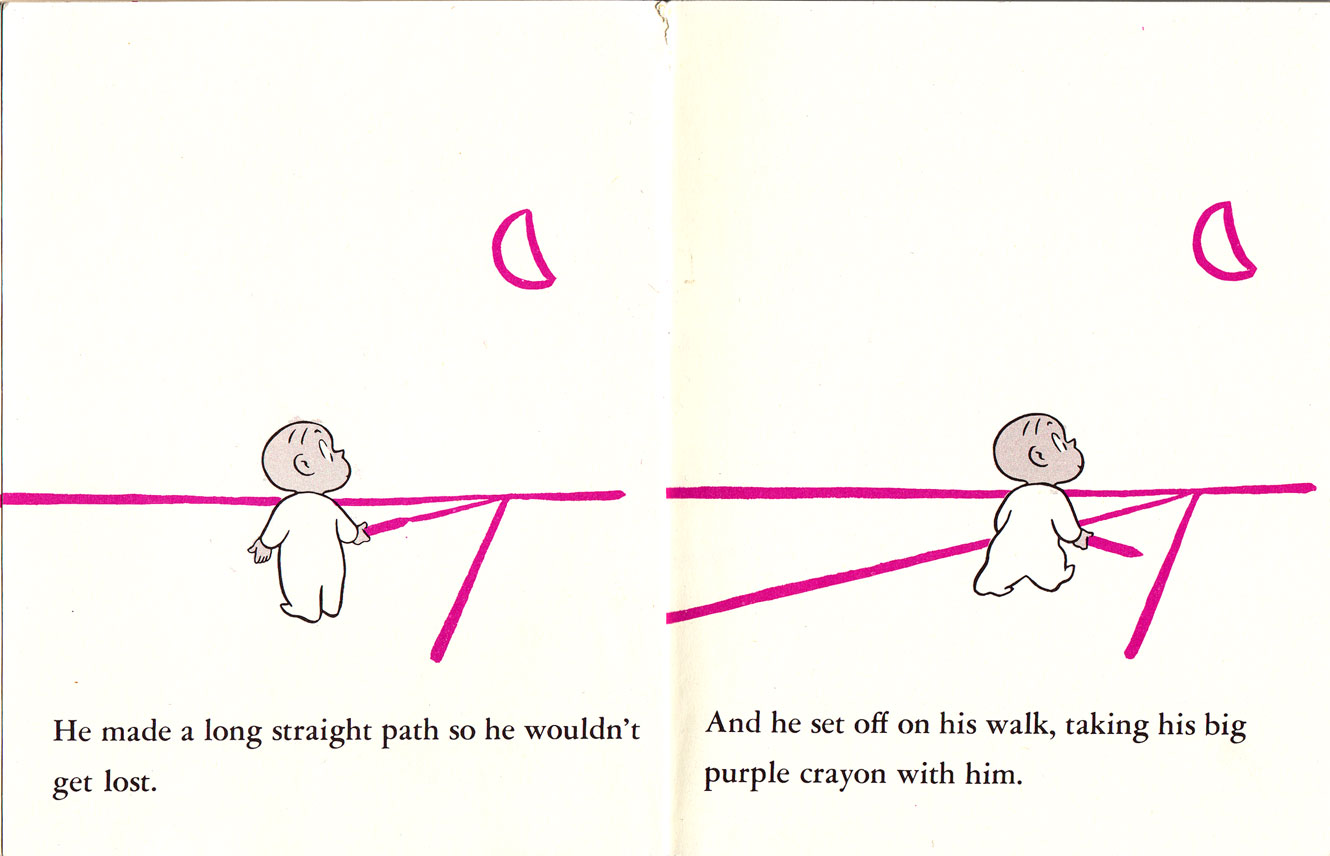

Thanks to the stylistic consistency of Johnson’s clear line, Harold and his artwork all inhabit the same reality. Their shared aesthetic allows Johnson to convince us that, for example, oscillating between two and three dimensions is perfectly normal. Or, at least, this oscillation – which begins at the moment when Harold draws the path – convinces most people. It puzzled both of Johnson’s editors. Looking at Johnson’s dummy, his editor Ursula Nordstrom said, “I found myself asking such dumb questions – like where did he draw the moon and the path and the tree?” First among a list of “The parts I am not too sure of,” Harper reader Ann Powers also named “the pathway at the beginning (too strange?).” It may be strange, but when Harold is standing in an empty void, it also makes sense for him to draw a “long straight path.” It’s practical. It anchors him. It also creates the illusion of three dimensions in what has – up to this point – been a two-dimensional space. Unlike most pre-schoolers, Harold understands the vanishing point.

In one sense, the observation that “he didn’t seem to be getting anywhere on the long straight path” echoes such advice as “taking the road less traveled” or “getting off the beaten path.” Harold’s decision to leave it announces his creativity. In another sense, the observation is literally true. His drawing only appears to have three dimensions. He’s actually on a flat page. The most he can do on this “path” is walk in place. To get anywhere, he needs to acknowledge the flatness of the page and walk off the path, into a new space, blank and ready for his crayon.

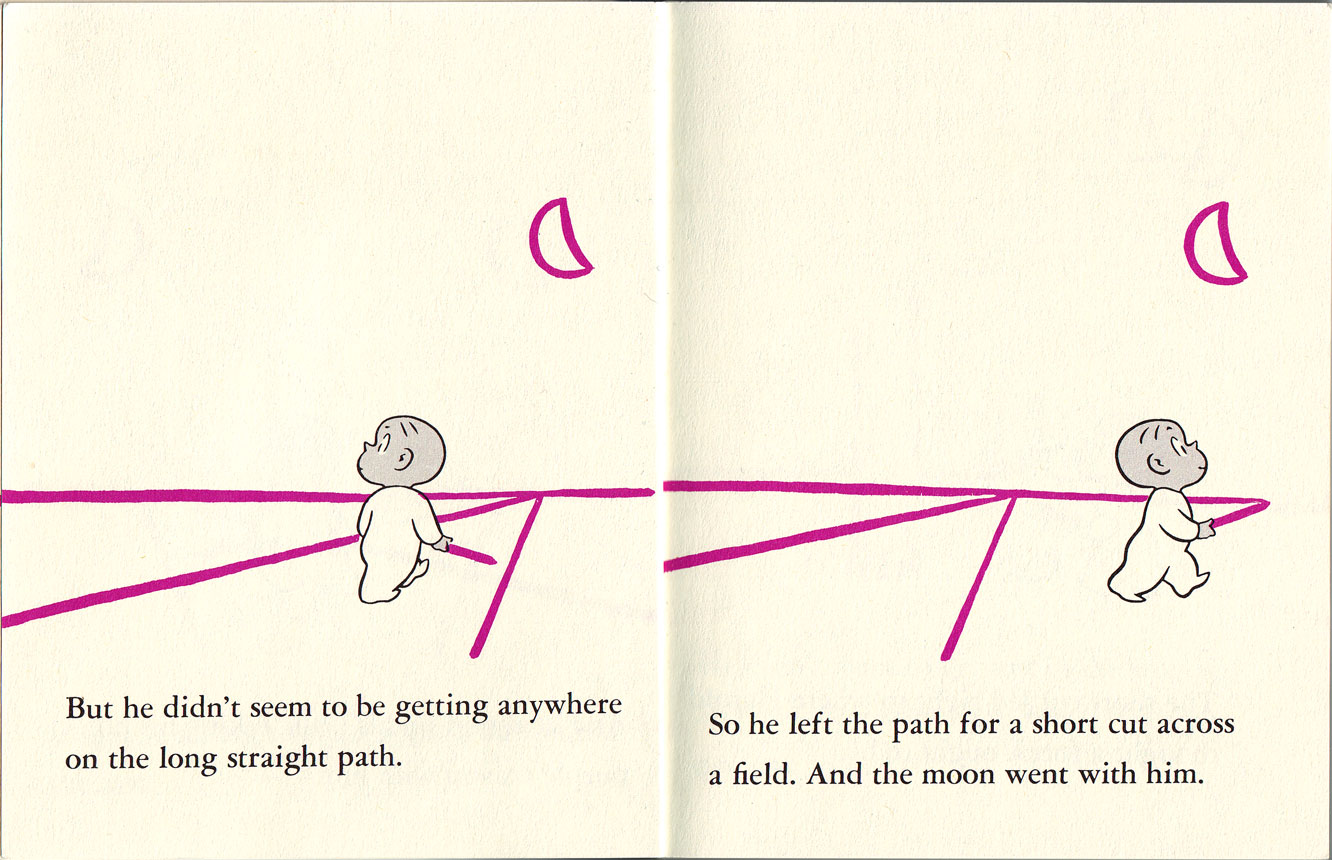

As he departs from the path, “the moon went with him” suggests a three-dimensional reality – even though only some of Harold’s drawings actually have three dimensions. The dragon and boat are 2-D. The pies and picnic blanket are 3-D. The balloon begins as one-dimensional (a curved line), becomes two-dimensional (a circle), and ends as three-dimensional (two ropes extending behind, and two ropes in front). But its basket stays two-dimensional, as does the house it lands in front of. Yet these differing numbers of dimensions (often on the same page) don’t seem inconsistent or out-of-place because the moon helps trick us into seeing these scenes in a three-dimensional space. When we walk at night in the real, physical world, the moon seems to follow us. The moon is the only part of Harold’s drawing that’s able to move, hovering over his head, far off in the distance, as he walks along.

Though neither named in the title nor represented on the cover, the moon is as important as Harold and his crayon. Perhaps acknowledging the moon’s key role in this trio, two later Harold books feature the moon on the cover: next to a tightrope-walking Harold on Harold’s Circus (1959) and as the “D” on Harold’s ABC (1963). The moon is Harold’s companion throughout Harold and the Purple Crayon, and the third constant visual motif. After its introduction, the moon appears in every scene (every page or two-page spread, in the four “city” pages) – along with the two other constants (Harold and his crayon). Harold might be read as a stand-in for the reader, the crayon as his (or our) imagination, and the moon a guiding light. Or, better: Harold is the artist, the crayon his medium, and the moon his muse.

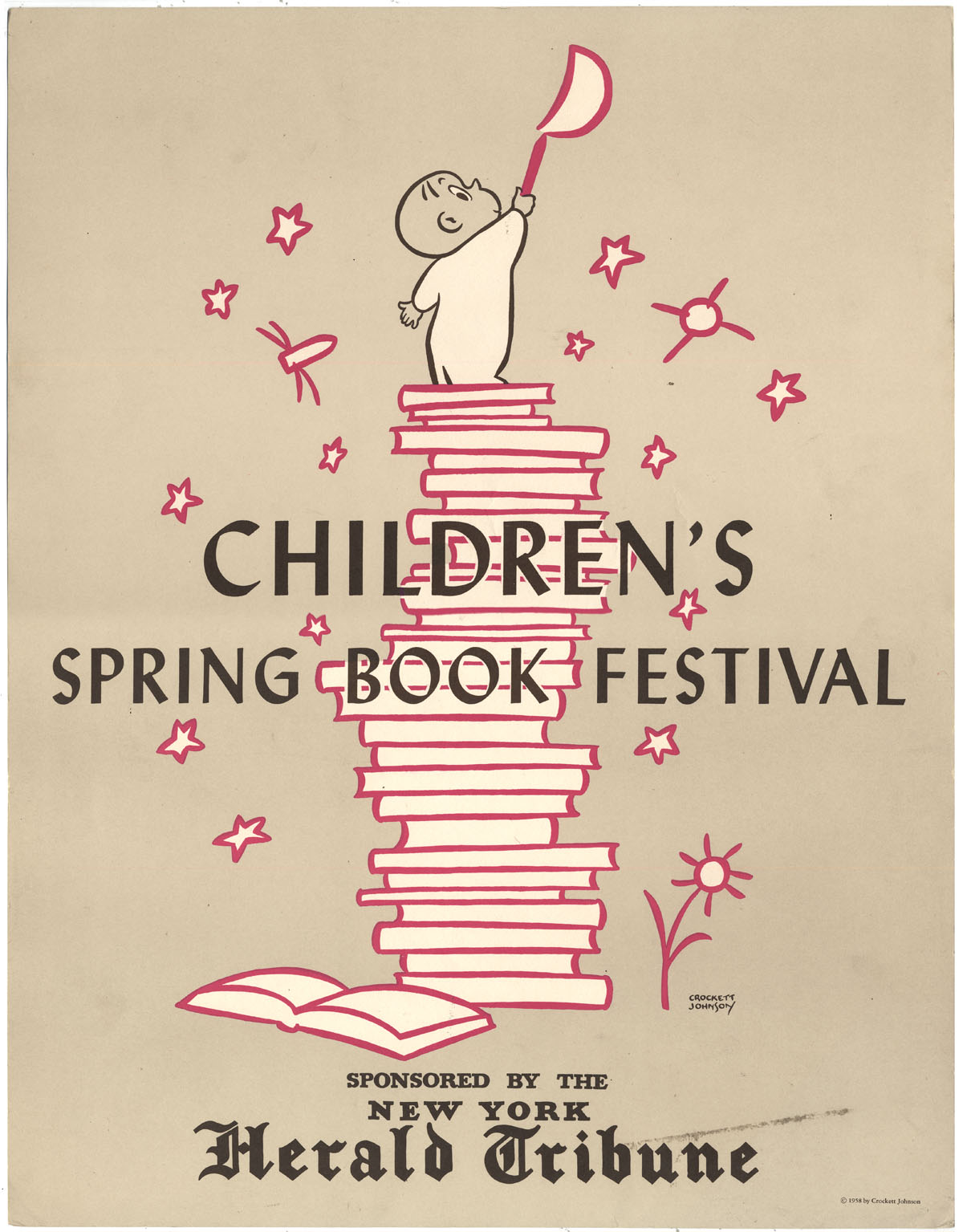

Crockett Johnson’s poster for the 1958 New York Herald Tribune Children’s Spring Book Festival courtesy of Chris Ware.

Fans of Harold might also enjoy these:

- Harold is 60. So is his purple crayon (20 Oct. 2015). On the occasion of Johnson’s 109th birthday, tributes to Harold from Lane Smith, Bob Staake, and others.

- A Manifesto for Children’s Literature; or, Reading Harold as a Teen-Ager (21 Sept. 2015). An essay of mine in the the Fall 2015 issue of The Iowa Review.

- The Archive of Childhood, Part 1: Crayons (27 Dec. 2014).

- Harold Around the World (20 Oct. 2014). Harold and the Purple Crayon has been published in many languages. Here are some of the covers.

- A Very Special House (30 Sept. 2014). A visit to the house where Crockett Johnson wrote Harold and the Purple Crayon.

- How Much Is That Harold in the Window? Harold at Compas, L.A. (10 May 2014). Full post for image reproduced above.

- Happy 107th Birthday, Crockett Johnson! (20 Oct. 2013)

- Crockett Johnson in New York: A Walking Tour, in Honor of His 106th Birthday (20 Oct. 2012). The childhood homes of Crockett Johnson.

- Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: Chris Ware’s cover (9 May 2012). Chris Ware’s cover for my biography is beautiful.

- Harold and the Purple TARDIS (2 April 2012). Full post for image reproduced above.

- Harold and the School Mural (22 Jan. 2012)

- Happy Birthday, Crockett Johnson! (20 Oct. 2010)

- The Purple Crayon’s Legacy, Part I: Comics & Cartoons (13 Sept. 2010)

- The Purple Crayon’s Legacy, Part II: Picture Books (23 June 2013)

Cat

Philip Nel

Amy

rockinlibrarian

Philip Nel

Pingback: 2017 Fall LIS 7210 Library Materials for Children | sarahpark.com