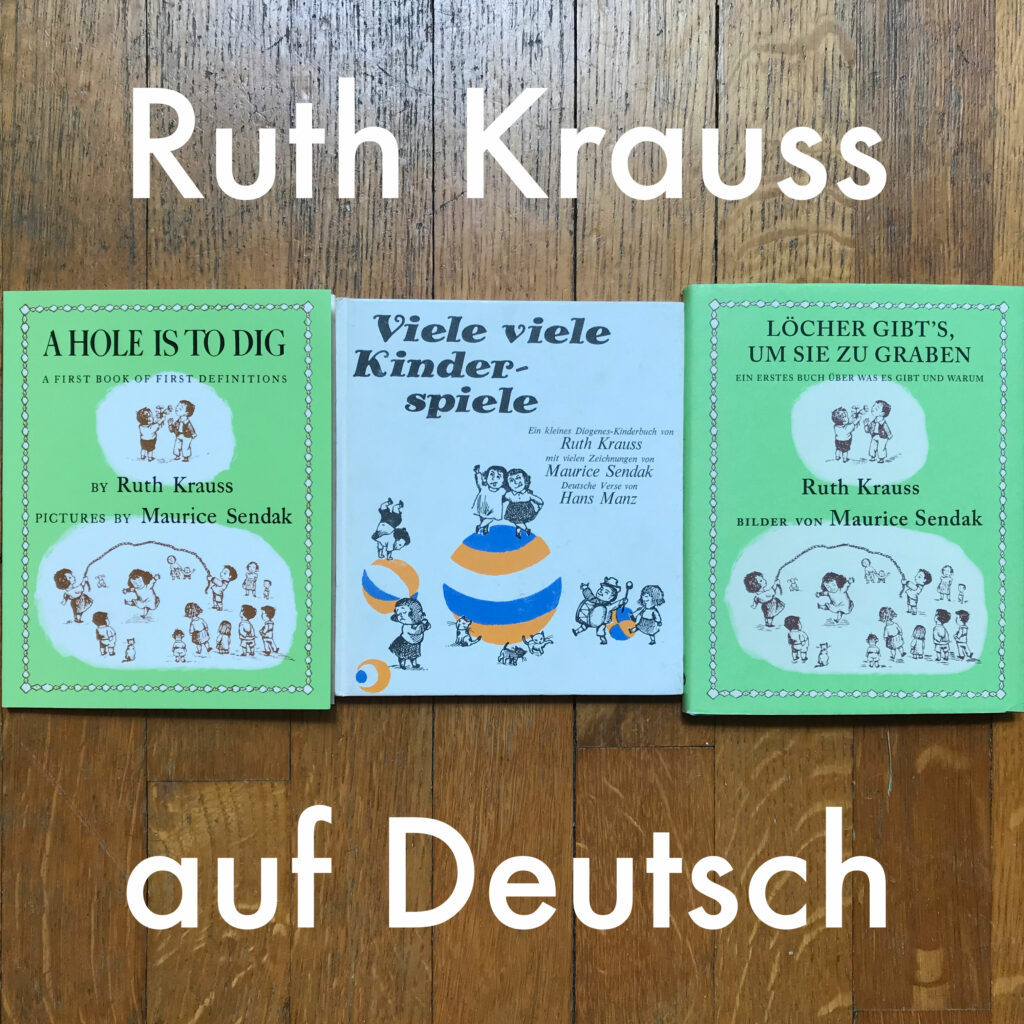

translated as Viele Viele Kinder-spiele (1968) & Löcher gibt’s um sie zu Graben (2016).

How do you translate children’s colloquial speech – with its flexible syntax, unusual diction – into another language?

In celebration of Ruth Krauss’ 119th birthday (or what she would have called her 109th birthday), I’ll sketch two possible answers to that question by looking at A Hole Is to Dig in the language her grandmother spoke: German! (Her father’s mother was born in Frankfurt in 1848.)

Krauss’s most famous book, A Hole Is to Dig: A First Book of First Definitions (1952) launched the career of its illustrator Maurice Sendak and, as its subtitle suggests, allowed children to define the world on their own terms. Krauss, who had a natural rapport with children, listened to 4- and 5-year-olds, and took notes on their definitions. As I note in my biography of Krauss and her husband Crockett Johnson, the book’s title came from a conversation she had with a boy on the beach. “What is a hole for?” she asked. The child said, “A hole? A hole is to dig” (Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss 122). As Sendak said, Krauss was “the first to turn children’s language, concepts, and tough little pragmatic thinking into art” (131).

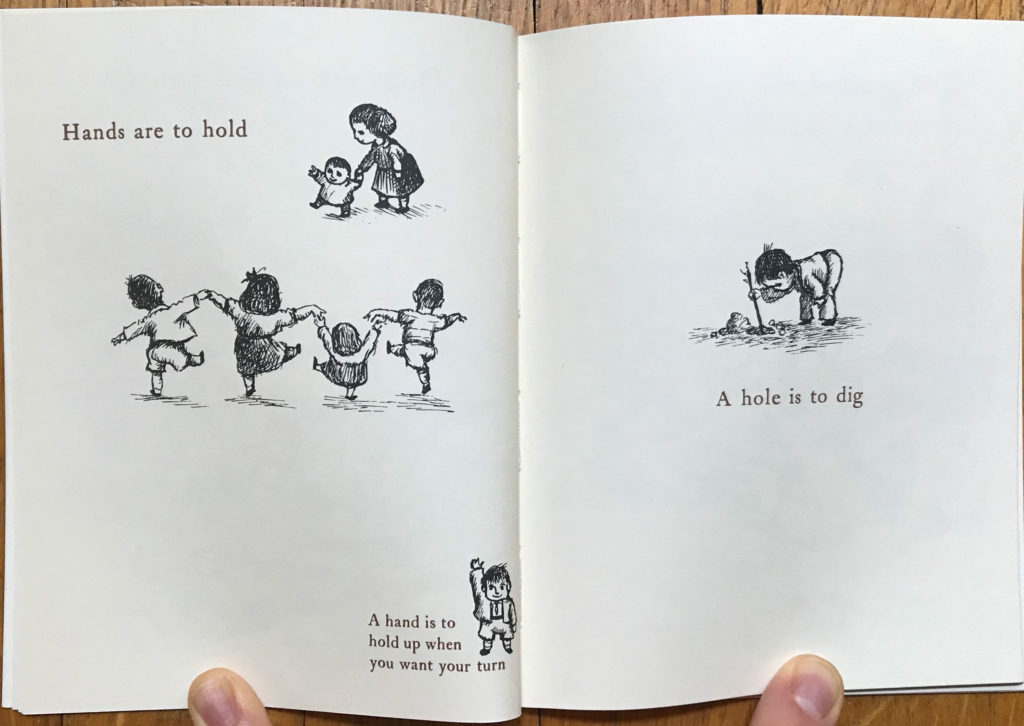

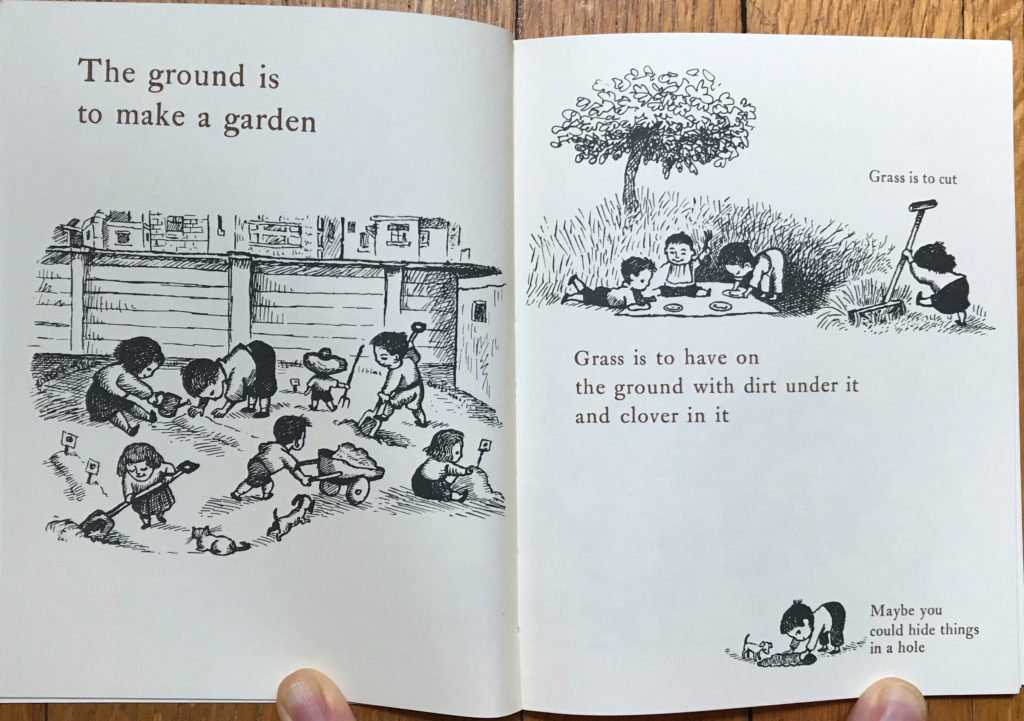

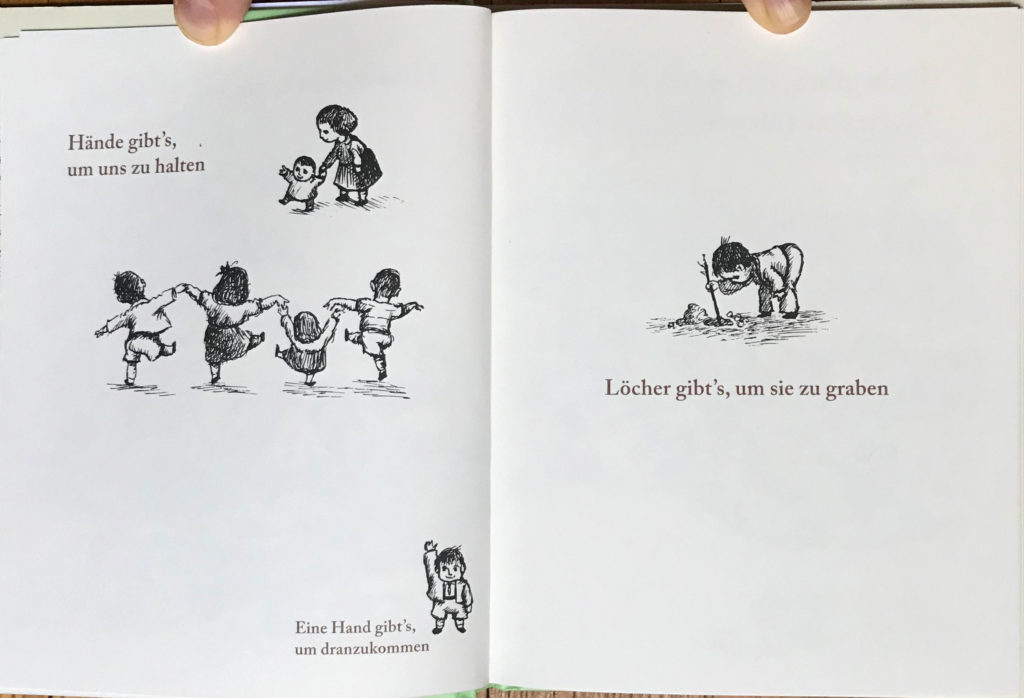

The result is a concept book held together by Sendak’s art and Krauss’s selection and ordering of the definitions. There’s an associative logic to the sequence. On the page before “A hole is to dig,” Krauss offers “Hands are to hold” – the near rhyme of “hole” and “hold” tying them together. On the two-page spread after “A hole is to dig,” she gives us a two-page spread with a series of outdoor activities, including dirt and a hole: “The ground is to make a garden,” “Grass is to cut,” “Grass is to have on the ground with dirt under it and clover in it,” and “Maybe you could hide things in a hole.”

I imagine that, were you to ask German children “Wofür ist ein Loch?” (“What is a hole for”?) their language might lead them in other directions. So, how ought a translator create German text that both compliments Sendak’s artwork and renders a version of Krauss’s arrangement of children’s speech?

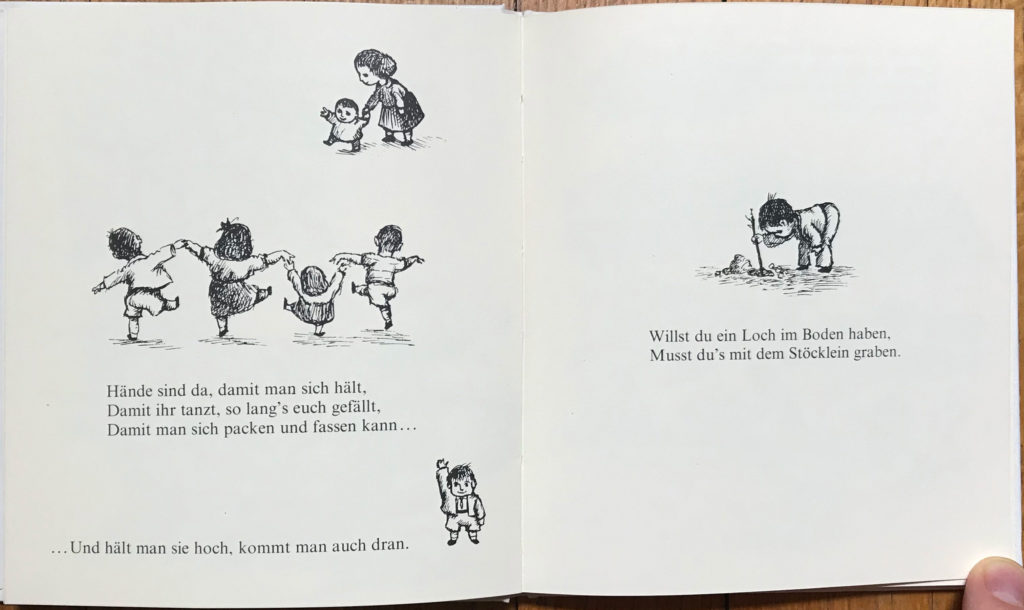

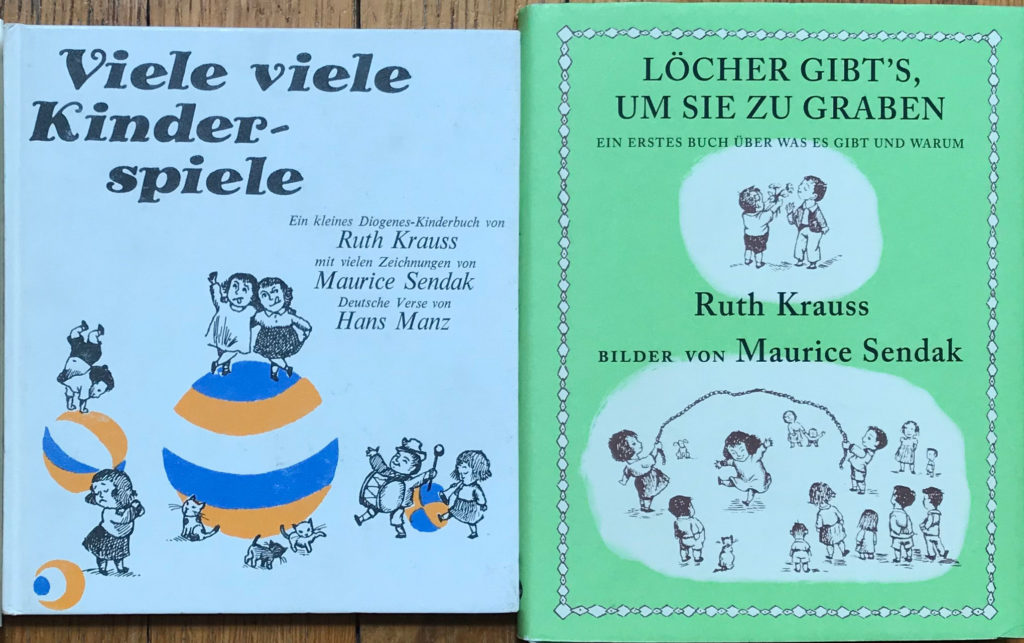

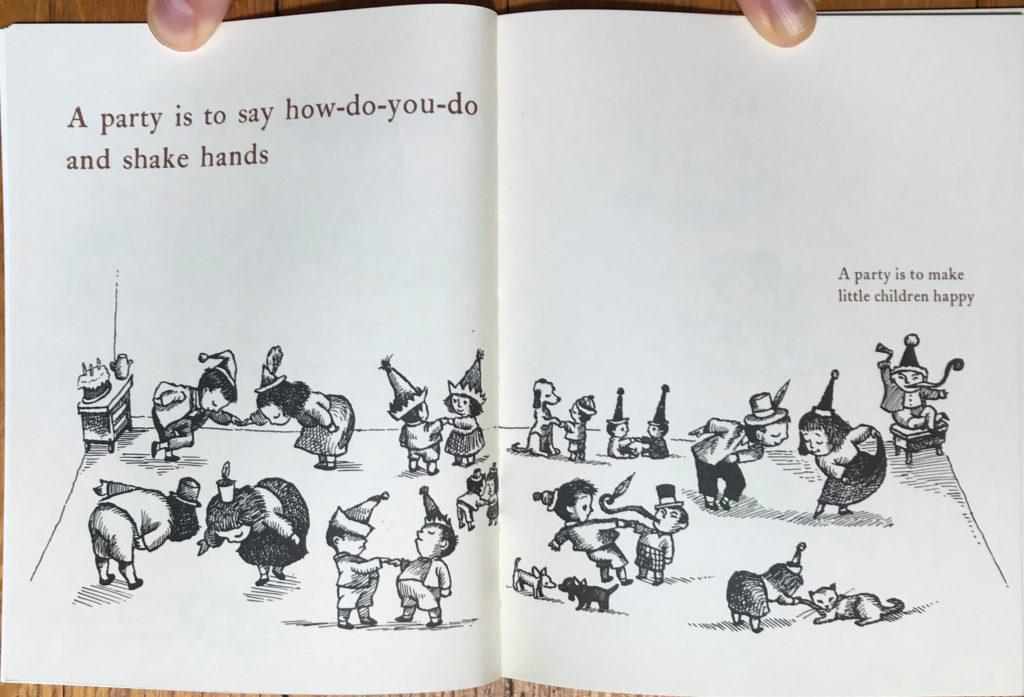

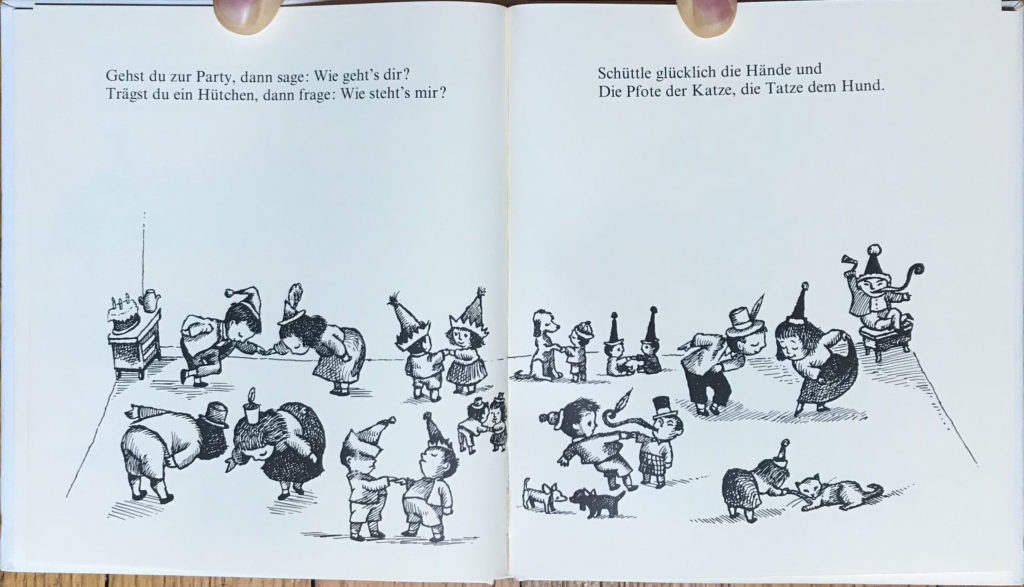

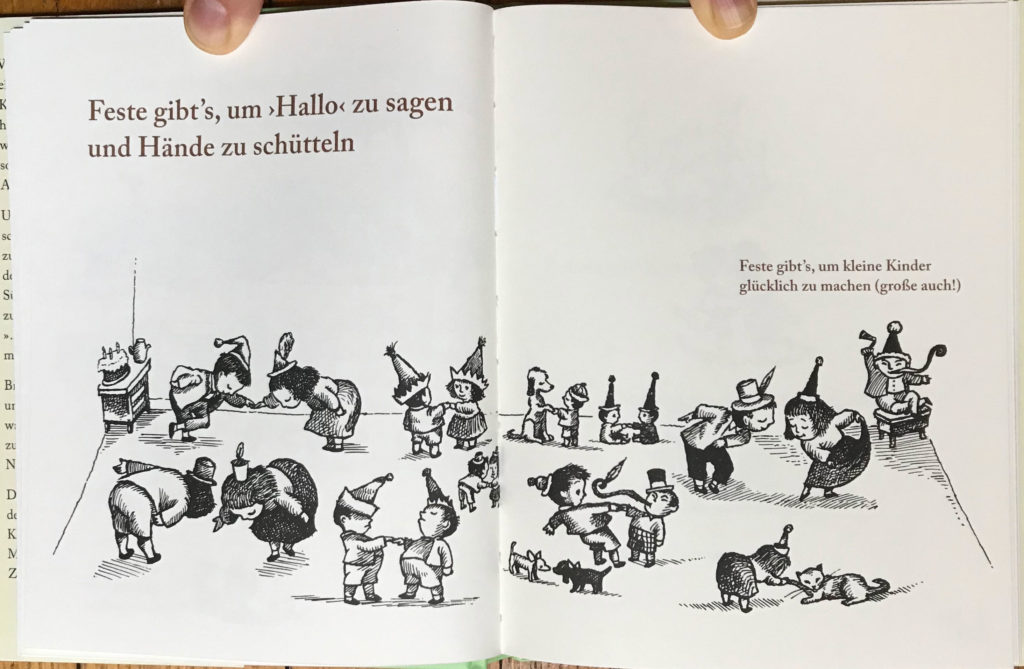

Two different translators had two quite different answers. Hans Manz’s 1968 translation, Viele viele Kinder-spiele, invents new verse that interprets the illustration. Ebi Naumann’s 2016 translation, Löcher gibt’s, um sie zu graben: ein erstes buch über was es gibt und warum strives to render a version of Krauss’s colloquial American text.

For the “A hole is to dig” page, Hans Manz has invented this verse:

Willst du ein Loch im Boden haben,

Musst du’s mit dem Stöcklein graben.

That translates to:

You want a hole in the ground,

You must dig with a little stick.

Incidentally, Stöcklein is a portmanteau created for the rhyme here. Stock is stick. Klein is little. So, Stöcklein would be little stick. I’m not sure why the o acquired an umlaut, unless that has something to do with the dative case?

UPDATE, 27 July 2020. Martin de la Iglesia (in the comments, below) offers this helpful addition:

“Stöcklein” is a regular (though somewhat archaic, compared to the more common “Stöckchen”) diminutive form of “Stock”. In German diminutives, the vowels a, o, u may turn into their corresponding umlauts (usually when in the final syllable).

Or maybe this has something to do with the rules governing German portmanteaus. The German language loves combining words in this way. For instance, Massenarbietslosigkeit means mass unemployment because – if my understanding is correct (and it may not be) – it’s Massen (mass) + Arbeit (work/employment) + los (off) + ig (adjectival ending) + keit (ness).

Right. Back to the books….

If Manz’s verse merely offers instructions for digging, Ebi Naumann has tried to retain some of the more poetic, intended effect of the original: “Löcher gibt’s, um sie zu graben,” which means Holes (Löcher) are there (gibt es) in order to dig them (um sie zu graben).

Naumann’s version of the book also uses that line as its title and Sendak’s cover art for its cover art. Manz, however, calls his translation Viele-viele Kinder-spiele, which means many-many children’s games. Echoing its loose approach to translation, the Manz version also throws out Sendak’s cover. It creates a new one comprised of four striped balls (presumably created by a designer at Diogenes Verlag AG, the Swiss publisher), and a mash-up of Sendak artwork from four separate places in A Hole Is to Dig: three girls (two on the ball, one next to it) making faces from “A face is so you can make faces,” kittens from the “Cats are so you can have kittens” page, a child standing on his hands from opposite the “Hands are to eat with” page, and two children from “The sun is so it can be a great day” page. I don’t know Sendak’s reaction to this cover (presuming he saw it), but I would bet he wasn’t pleased.

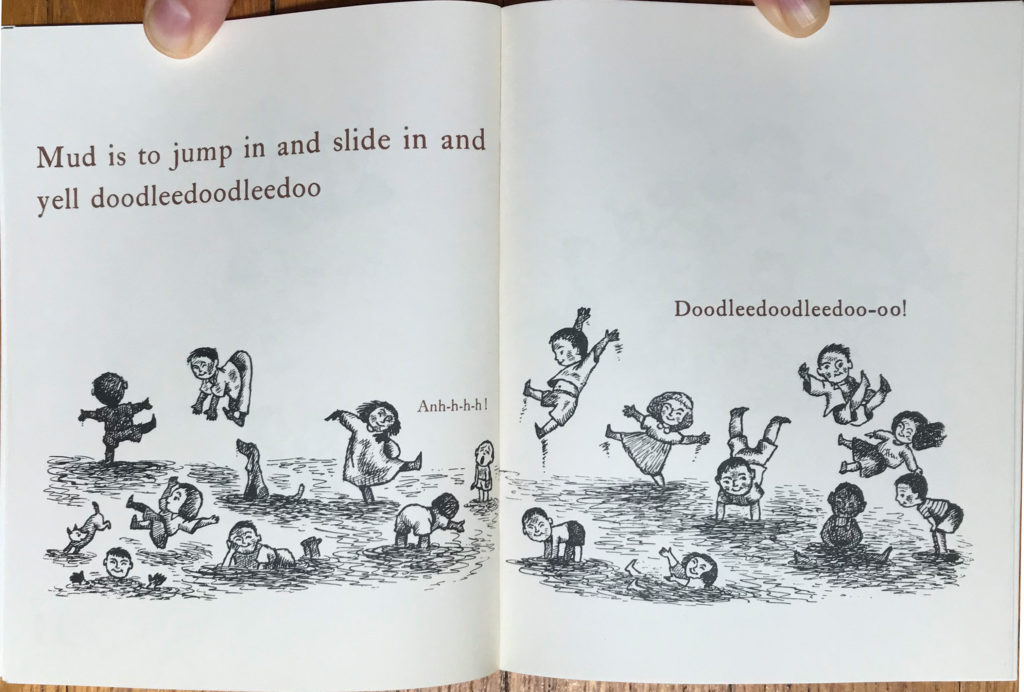

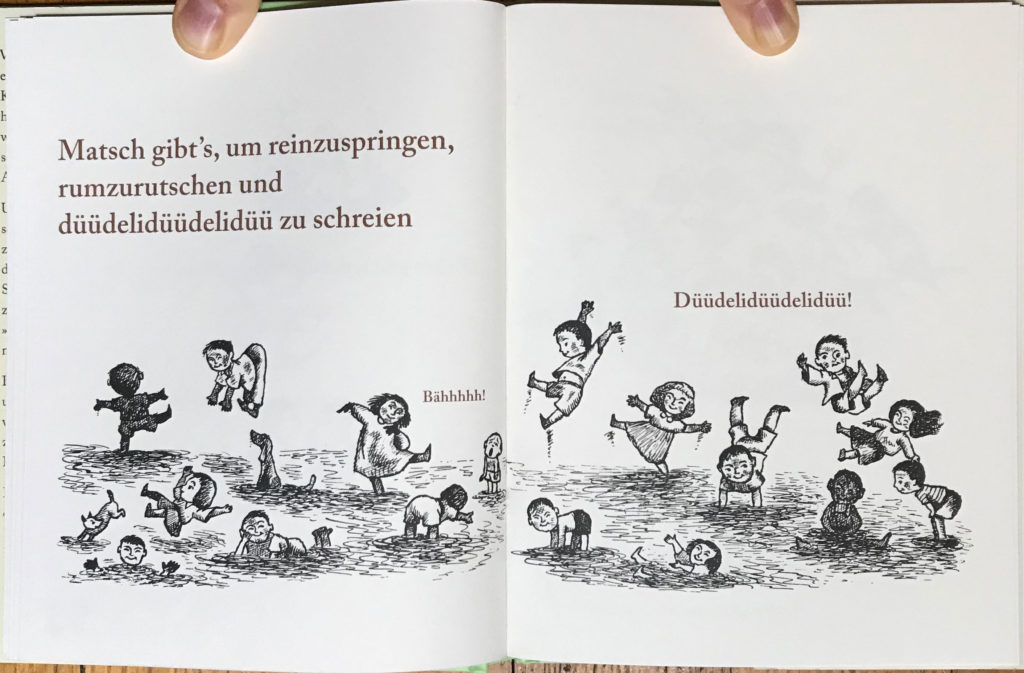

One of my favorite translation questions is “How do you translate the onomatopoetic and the nonsensical?”

Naumann’s 2016 translation offers a nearly sound-for-sound “doodleedoodleedoodleedoo” in its “düüdelidüüdelidüü,” though it does omit the final “oo” (or “üü”) on the second iteration of the exclamation. The other words are German versions of the English. The verb reinzuspringen is to jump into – a combination of springen (to spring towards) and rein (which can mean many things, but here might signify in one of its adverbial senses of entirely or outright). The verb rumzurutschen is to slide around: rutschen is to skip, to slide, to skid; zu is a preposition meaning to, toward, at; I don’t know how rum functions here. The verb schreien means to scream, to shout, to yell.

UPDATE, 27 July 2020. More help from from Martin de la Iglesia (in the comments, below)!

The “rum” in “rumzurutschen” is short for “herum”, a preposition meaning “around” as in “to slide around”. The “zu” is only there as an infinitive marker, equivalent to the “to” in “to slide around”.

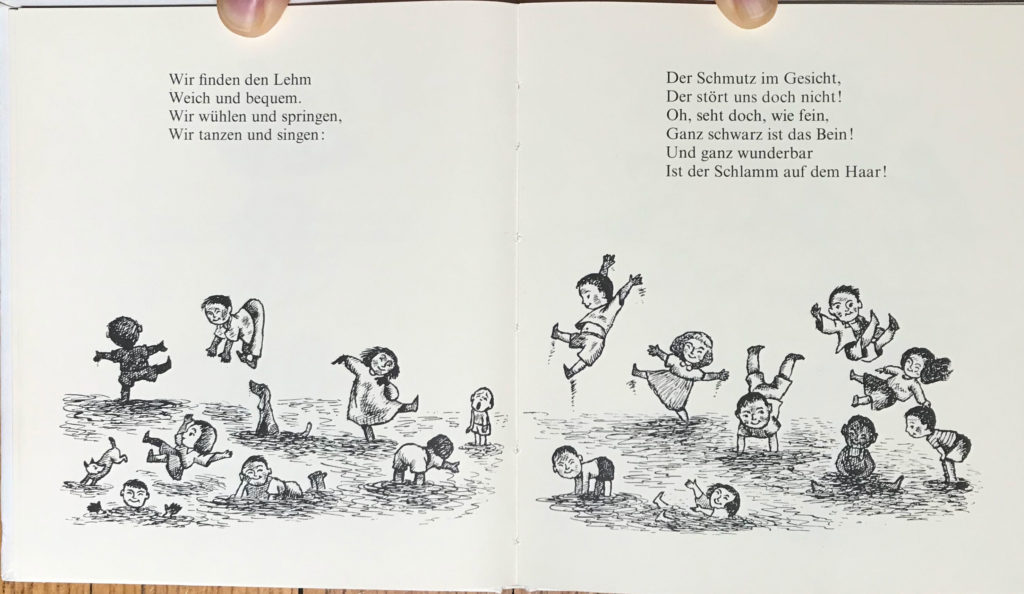

In contrast, Manz again composes some original verse inspired by Sendak’s art:

Wir finden den Lehm

Weich und bequem.

Wir wühlen und springen,

Wir tanzen und singen:

Der Schumtz im Gesicht!

Der stört uns doch nicht!

Oh, seht doch, wie fein,

Ganz schwarz ist das Bein!

Und ganz wunderbar

Ist der Schlamm auf dem Haar!

A translation of Manz’s verse might be:

We find the mud

Soft and comfortable.

We dig and jump,

We dance and sing:

Dirt in the face!

It does not bother us!

Oh, yes, see how pretty

is my entirely black leg!

And quite wonderful

Is the mud on your hair!

Though certainly aligned with the artwork, Manz’s verse also seems to offer an explanation for the picture. In contrast, Naumann’s version lets the image speak, by keeping the text brief – just as it is in Krauss’s version. Manz insists on describing each image, but Naumann respects the interplay of word and image that makes a successful picture book.

I am not a scholar of translation, and I’m only as far as German 4 at the college level. (I started learning the language in 2018, prior to a fellowship at the Internationale Jugendbibliothek in Munich.) So, my apologies for the deficiencies of this hastily written analysis. Corrections would be most welcome!

I hope that, forgiving (or, better, correcting) the limitations of my commentary, you have enjoyed glimpses from two German versions of A Hole Is to Dig.

And: Happy birthday, Ruth Krauss!

Thanks to Ada Bieber for introducing me to Mariela Nagle’s Mundo Azul bookshop in Berlin – that’s where I found Naumann’s 2016 translation last July. And thanks to Eric Reynolds for sending me Manz’s 1968 translation, earlier this year.

Thanks also to those who have tried to teach me German, from formal instruction (Ljudmila Bilkić, Christine Patry) to German friends who have offered guidance (notably, Ada Bieber, Jochen Weber, Claudia Soeffner, Ute Dettmar). Please credit them with any successes in my translation, and know that the deficiencies are my responsibility alone. Indeed, had I not been writing this the day before Krauss’s birthday, I am sure that any of these good people would have checked it for me. But… I was running behind.

Some (though not all) of my other posts on Ruth Krauss:

- Ruth Krauss, Sergio Ruzzier, and… the Beatles? (17 Oct. 2019)

- Ruth Krauss in 1951 (25 July 2018)

- Happy Birthday, Ruth Krauss! (25 July 2017)

- A Very Special House (30 Sept. 2014)

- Wild Things, I Think I Love You: Maurice Sendak, Ruth Krauss, and Childhood (11 May 2014)

- It’s a Wild World: Maurice Sendak, Wild Things, and Childhood (15 Oct. 2013)

posts on Germany

Martin

Philip Nel